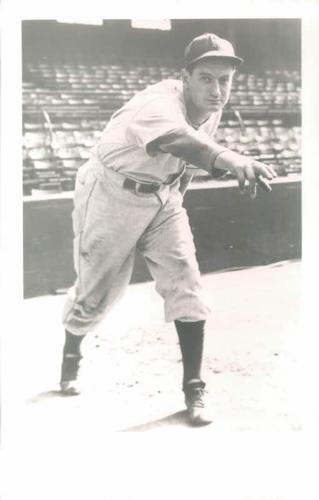

Don Black

The story of Don Black is a tragic one. A pitcher with a strong, live arm, he pitched two no-hitters in the minor leagues and one in the majors. He had many chances to make the most of his ability and succeed in his baseball career, but Don Black was an alcoholic. And like many people who battle that disease, he was never fully able to beat it, and never reached the heights that his talent might have taken him. Ironically, it was not alcoholism that eventually ended his career.

The story of Don Black is a tragic one. A pitcher with a strong, live arm, he pitched two no-hitters in the minor leagues and one in the majors. He had many chances to make the most of his ability and succeed in his baseball career, but Don Black was an alcoholic. And like many people who battle that disease, he was never fully able to beat it, and never reached the heights that his talent might have taken him. Ironically, it was not alcoholism that eventually ended his career.

Donald Paul Black was born on July 20, 1916, in Salix, Iowa, the youngest of 14 children (nine boys, five girls) born to William and Margaret Black. Like his siblings, Black spent a good amount of time helping out on the family farm. Salix was a small, sprawling town. The 1910 United States Census estimated the population at around 390. There were not enough boys to form a baseball team at the local high school, but Black was on the basketball team. He also participated in softball, and it was this sport that led him to his first professional baseball team.

In 1937 a friend got him a tryout with Fairbury of the Class D Nebraska State League. Fairbury was a farm team of the St. Louis Browns. Originally an infielder, Black was switched to pitcher. But he did not fare well, posting a 5-11 record with a 4.85 ERA in 1937. Regardless, Fairbury folded operations and Black was out of work.

He went to California and worked in construction while he was away from baseball, although he played some semipro ball. Two years later he resurfaced in Blackstone, Virginia, where he married the former Joyce White on February 17, 1940. The couple had two daughters, Margaret Stephen and Donna Meade. When asked about his daughters’ unique names, Black explained that his wife’s family were direct descendants of one of the first families of Virginia. His daughters’ middle names honored distinguished relatives. “The White plantation was burned down during the Civil War,” said Black. “My wife’s mother still keeps a picture of her uncle — a picture that shows the heel mark where some Yankee soldier stepped on it.”1

Black bought out his contract with the Browns for $300. He then hooked on with Petersburg of the Class C Virginia League in 1941, posting an 11-5 record with a 2.35 ERA. He followed it up with an 18-11, 2.49 ERA season in 1942. In each season, Black fired a no-hitter. The first came on July 22, 1941, a 1-0 win over the Staunton Presidents. The second occurred on August 4, 1942, a 4-0 victory over the Pulaski Counts. Based on his fine performance, Philadelphia Athletics’ owner Connie Mack paid $5,000 for his services.

Black, at 26 years of age, may have been considered on the older side for a rookie when the A’s 1943 season commenced. Black lacked control on the mound, issuing 110 walks against 65 strikeouts. His record reflected his troubles, as he went 6-16 with a 4.20 ERA in 1943 –discouraging enough, but perhaps even more so because Black was pitching against “watered-down” lineups. Many major leaguers had been called up to serve in World War II.

On the other hand, the war effort may have been one of the reasons Black made the jump from a Class C club to the majors. Every club was searching for pitching help at all levels amid the shortage of pitchers.

Black reached double digits in wins in 1944, but still posted a losing record at 10-12. For the only time in his career, his strikeouts (78) outnumbered his walks (75).

Unfortunately for Black, his performance on the mound was hindered by his addiction to alcohol.

Mack tried every possible method of persuasion on Black in an effort to set him on the path to sobriety. But his efforts did not have a lasting effect. It all came to a head in Boston on June 5, 1945. At the Somerset Hotel, Black joined Dick Siebert, Al Simmons and Charlie Metro for breakfast. Black ordered a bowl of split pea soup. “We’re eating our eggs and he’s fumbling with the spoon to eat his soup,” said Metro, “and Simmons moves over a little to block Mr. Mack’s view of what’s going on, and the guy leans over to spoon up some soup and falls face down right into the bowl. We’re all moving in close to try to cover it up and Connie Mack says, ‘You don’t have to do that. I’ve seen it.’”2

As a result, Mack suspended Black for 30 days without pay. Black returned home to Petersburg, where he took a job pumping gas.3 “Black has broken training on several occasions this season,” said Mack. “The last time, I warned him I would do something about it the next time. He has been a detriment to the club and he has to suffer the penalty.”4

Black returned to the Athletics on July 8, with Mack admonishing him that this was his last chance. He went 4-8 the remainder of the season to finish at 5-11 with a 5.17 ERA. Five days after the season ended, on October 2, 1945, Mack sold Black to Cleveland for $7,500. Mack gave some advice to Cleveland general manager Roger Peckinpaugh. “He should be a great pitcher, but he’s a bad boy,” Mack told Peck.5

Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau had pushed for the acquisition of Black. Despite knowing of his issues with alcohol addiction, Boudreau knew that Black could perform when he was right.

Black showed some of that bad-boy image at the team’s spring training hotel in Clearwater. One night, Black went in search of Peckinpaugh, looking for an advance on his salary. He had been drinking and was slurring his words. Cleveland News sportswriter Ed McCauley urged Black to return to his room, but the pitcher would have none of it. “Can’t do it,” mumbled Black. “Got to have some money — right now. I don’t care about myself. The club is paying my board. But unless Peck will give me some money to send home, I’ve got to quit this team and get a job somewhere. I’m not going to have my family worry about money.”6

When Black located Peck, who was with Boudreau, he asked for an advance. Peckinpaugh refused, saying that he had already loaned him $1,500. There was a heated argument, with Black storming out of the room. Boudreau intended to fine Black. “He broke the training rules,” said Boudreau. “He was intoxicated in the hotel lobby, in front of the ballplayers.”7 McCauley pointed out to Boudreau that other players — he would not name names — were doing the same activity, but were smart enough to do it away from the hotel. The next morning, Boudreau changed his mind and did not fine his new pitcher. “Please don’t write anything about my fining Black,” said Boudreau. “I’m not fining him. I’m giving him another chance.”8

Bill Veeck appeared in Cleveland in 1946, having purchased the franchise from Alva Bradley. Black only started four games for the Indians that year; he was mostly used out of the bullpen. The Indians optioned him to Milwaukee of the Class AAA American Association on July 16 for the remainder of the Brewers season. Black fared no better, going 0-5 for the Brewers with a 5.18 ERA. He was not recalled to Cleveland after the Brewers’ season ended.

Black’s career looked to be over when Veeck stepped in and recommended Alcoholics Anonymous. “Give this thing a try,” said Veeck. “You won’t have to worry about your debts. I’m paying them all off. The only man you’re going to owe is me, and I’m not going to be tough on you. I know the AA people. I’m going to send them around to see you.”9

It was a momentous step for Black, who showed positive signs for recovery. Veeck, who had the reputation of never giving up on another person, was Black’s strongest advocate. On April 29, 1947, Black lost, 4-3, to Philadelphia at Cleveland Stadium. The A’s scored the winning run in the top of the ninth inning when Black walked Ferris Fain with the bases loaded. Indeed it was a tough way to lose a ballgame. Unbeknownst to Black, Veeck had a couple of his close friends from AA in the clubhouse after the game to offer support to Black.10

When Black’s father passed away in California later that year, Veeck made sure that members from the local AA chapter would be on hand to support Don during his time of grief.11

Black’s signature win occurred on July 10, 1947. Cleveland hosted Philadelphia as the second half of the season got underway. Black, who entered with marks of 6-5 and a 3.84 ERA, started the opener of a doubleheader against his old mates. The game was delayed 45 minutes after the top of the second inning. When play resumed, the Indians scored three runs, the second of which was scored by Joe Gordon on a bunt by Black.

Although Black had two hits in the game, it was his work on the mound that got the most notice. Black outhit the entire Athletics team as he tossed the first no-hitter in Cleveland Stadium history. The 3-0 victory was witnessed by 47,871 fans.

Black was far from dominant, issuing six free passes while striking out five. But he was just good enough to earn the no-no. In fact, the game had started off rocky as Black threw eight balls, issuing consecutive walks to Eddie Joost and Barney McCosky. After a groundout by Fain, Joost moved up to third base, but that was as far as any A’s baserunner would advance.

“He really had it tonight,” said Boudreau. “I went over in the seventh when he walked Fain to tell him to slow down a little. We all knew he was going for the no-hitter.”12

His old boss, Connie Mack, was more thrilled for Black the man than Black the baseball pitcher. “As we didn’t make any runs, I’m pleased that Don was able to pitch a no-hitter. Our boys said his slider was working wonderfully — that’s why he was so successful. I was especially glad for Don because — well, you know he’s taking better care of himself these days.”13

Although Black finished with a losing record in 1947 (10-12, 3.92 ERA), it was considered a productive season. In four of his 12 losses, the Indians offense was shut out. He started the second most games (28) on the team after Bob Feller (37).

With Bob Lemon’s transformation from outfielder to starting pitcher being successful, and the emergence of Gene Bearden, Black was once again used as a spot starter in 1948. An article on September 12, 1948, brought to public light Black’s battle with alcohol. Written by the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s Gordon Cobbledick in American Weekly (a Sunday magazine supplement), it was titled “Don Black’s Greatest Victory.” Cobbledick wrote, “Black has voluntarily renounced his anonymity, which is one of the foundation stories of AA, in order to publicize the job that the organization can do for the thousands who are as afflicted as he was.”14

The next day, Black got the start at home against the St. Louis Browns. In the bottom of the second inning, the Indians scored a run to take a 1-0 lead. Black stepped to the plate. After fouling off a pitch from the Browns’ Bill Kennedy, Black slumped to his knees and lost consciousness. He was rushed to St. Vincent Charity Hospital, where he was attended by Dr. Edward Castle. The diagnosis was that Black had suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage of the brain. An aneurysm caused blood to run into the spinal fluid. His brain, as well as his spinal column, was bathed in blood. “If no more hemorrhages develop, he might regain consciousness enough to recognize his friends tomorrow,” said Dr. Castle. “Then again, he might stay in the present condition for quite a while. At any rate, he is through with baseball for this season.”15

Veeck, though known as a showman, was acting from compassion when he held a “Don Black Day” at Cleveland Stadium on September 22. The game against Boston was switched from an afternoon affair to a night-time start. Boston manager Joe McCarthy balked at the switch, as Feller was on the mound and the Sox would rather face him in the afternoon light. But the game went on and Cleveland won, 5-2, to pull even with Boston in the AL pennant race.

Black’s teammates paid their way into the park as a sign of solidarity for the fallen pitcher. They walked through the turnstiles in full uniform, purchasing tickets as they entered. All of the gate receipts went to the cause for Black. A total attendance of 76,772 brought in more than $40,000.

The Indians won a tiebreaker for the pennant against the Red Sox, 8-3, on October 4 at Fenway Park. Boudreau said the following during an interview: “Thirty men helped us win this championship…you, Don Black are one of the most helpful. Every one of us who was able to carry on put out just a little more because you were unable to be with us. We won this for you, Don, and we want you to know how proud we are to call you a teammate.”16

Black also received a full share of the team’s World Series winning pot, which came to $6,970.

Black made a full recovery, and although Veeck signed him to a contract in 1949, he had lost too much strength and was unable to pitch. His baseball career had ended. His career mark was 34-55 with a 4.35 ERA.

Black, his wife Joyce, and their two daughters resided in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio. Don worked as a salesman in both the automobile and insurance industries. He also worked in the summer for the local recreation department. But it had been hard for Black to keep steady employment after his baseball career. His two biggest supporters, Veeck and Boudreau, were both far away from Cleveland by this time. Black’s membership in AA lapsed and he began drinking again.17 The money dried up, and he suffered frequent headaches and fainting spells.

On December 27, 1957, the Black family was on their way to Blackstone, Virginia, to spend part of the holidays with Joyce’s family. Black had a fainting spell and his vehicle veered off the road and crashed over a 20-foot embankment near Culpeper, Virginia. Don suffered a fractured skull and was taken to the University of Virginia hospital where he was treated for numerous head injuries and lacerations.18

On April 21, 1959, while at home watching an Indians game on TV, Don Black collapsed and was rushed to St. Thomas Hospital in Akron, where he was pronounced dead. He was 42. The cause of death was lung cancer.19 He is interred in McKenney, Virginia.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joe DeSantis, Norman Macht, and Rory Costello. It was fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Ed McAuley, “Black May Brighten Indians’ Pennant Ambitions,” Cleveland News, February 26. 1946: 17.

2 Norman Macht, Connie Mack: The Grand Old Man Of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015): 324.

3 Macht, 324.

4 “Black Suspended; Broke Training”, Philadelphia Inquirer, June 7, 1945: 22.

5 Tony Lariccia, “Cleveland Indians pitcher Don Black’s no-hitter 70 years ago was a triumph over alcoholism, but tragedy followed,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 9, 2017: S3.

6 Ed McCauley, “Black Never Forgot that Shining Picture,” Cleveland News, July 12, 1947: 10.

7 McCauley, “Black Never Forgot that Shining Picture.”

8 McCauley, “Black Never Forgot that Shining Picture.”

9 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, May 4, 1957: 8.

10 Paul Dickson, Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick (New York: Walker & Company, 2012): 151.

11Dickson, Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick, 151.

12 Charles Heaton, “Don Knew He Had No-Hitter On Fire,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 11, 1947: 15.

13 Heaton, “Don Knew He Had No-Hitter On Fire.”

14 Heaton, “Don Knew He Had No-Hitter On Fire.”

15 Harry Jones, “Pitcher Black in Critical Condition”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 14, 1948: 1.

16 Lariccia, S4.

17 Lariccia, S5.

18 Newspaper accounts did not mention whether the other Black family members were injured.

19 The HOF questionnaire was filled out by Joyce Black. In the space for cause of death, she wrote lung cancer.

Full Name

Donald Paul Black

Born

July 20, 1916 at Salix, IA (USA)

Died

April 21, 1959 at Cuyahoga Falls, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.