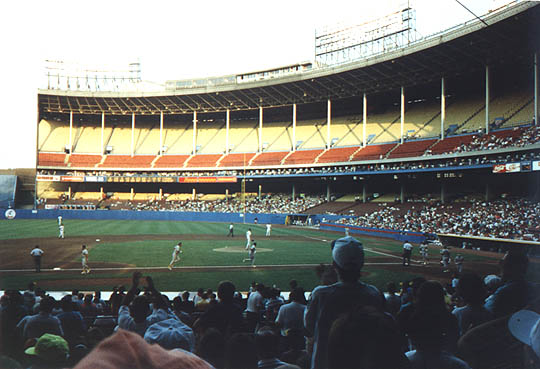

Cleveland Municipal Stadium

This article was written by Tom Wancho

Cleveland Municipal Stadium (1931-1996) housed millions of sports fans (boxing, baseball, football), music lovers (the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen), a Shriners convention, the Cleveland Orchestra, religious events, and circuses.

Known by Clevelanders as simply “the Stadium,” the steel and concrete behemoth enthused and impaled attendees for parts of seven decades. Its initial sporting event, on July 3, 1931, was a heavyweight championship match between defending champ Max Schmeling of Germany against William “Young” Stribling. The contender stayed on his feet until 14 seconds remained in the 15th round. The Schmeling-Stribling bout mirrored what would become the stadium’s history. If the champ was Cleveland’s weather, it threw punches at the contender (the Stadium) before reducing it to rubble.

Anyone who went to see the Stadium during the 1970s-1990s saw the wear and tear of standing alongside the windy, icy Lake Erie. Peeling paint, crumbling concrete, inoperable escalators and elevators, uncomfortable seats, flooded restrooms, misnamed luxury boxes, and obstructed views were a recipe for destruction. Thus it wasn’t a surprise, after the “original” Cleveland Browns moved to Baltimore following the 1995 NFL season, that the Stadium had outlived its use.

Open Sesame

At the first baseball game, a July 31, 1932, Sunday showdown against the Philadelphia Athletics attended by baseball royalty and 80,284 fans, baseball’s first commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, commented, “This stadium is perfect. It is the only baseball park I know where the spectator can see clearly from any seat. Look at those people out there (he said pointing to the crowded center-field bleachers); they can watch every play.”1

Landis turned around in his box seat near the Indians dugout and swept the grandstands with his hand. “Not a barrier to block anyone’s view. Comfortable chairs. This is perfection.” Obviously, the Commish never saw a game from beyond the Fat Cats box seats.

John Heydler, the National League’s president, said, “Marvelous. It is the last word in baseball parks. A great thing for baseball. And one should not forget to give (Indians President) Mr. (Alva) Bradley credit, either.”2

And this from Thomas S. Shibe, Athletics president: “This was built for baseball. I wish we had this in Philadelphia for the last three World Series.”3

Before the beginning

According to the October 1985 Inventory Nomination form for a listing on the National Register of Historic Places, “Cleveland Municipal Stadium was designed by the progressive city administration as a multipurpose structure to accommodate the great surge in attendance at baseball and football games and other public spectacles that occurred with the rise of the automobile.”4

The nomination form goes on to read, “Since then, in addition to baseball and football, the range of activities at the stadium has included religious convocations, the Metropolitan Opera, the Beatles, circuses, rodeos, big bands, tractor pulls, and polka festivals.”5

If you build it … who will come?

Constructed on a landfill that stretched the lakefront 200 feet farther into Lake Erie, the facility was completed in 370 days at a cost to taxpayers of $3,035,245. Although 21 percent over budget, the cost overruns were attributed to the addition of a scoreboard, sound system, and infrastructure around the facility, including bridges, railroads, and road work.

After their July 31, 1932 “opener” at the Stadium, the Indians played by Lake Erie for the remainder of 1932 and all of the 1933 season. But after attendance dipped in 1933 to 387,936 – nearly 100,000 less than the 483,027 they attracted in 1931 at their last full season at League Park, team owner Alva Bradley moved his club back to the significantly smaller League Park for all but one game during the 1934-36 seasons.

Under pressure from city leaders, unhappy at their 80,000-seat stadium standing vacant, Bradley agreed to play most doubleheaders and other games expected to draw larger crowds at the Stadium. The Tribe did not move downtown full time until 1947, after Bill Veeck purchased the club.

On July 16, 1945, the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League played their first regular-season game at the Stadium, defeating the Birmingham Black Barons, 6-2, in front of 12,733 fans. The Buckeyes won five regular-season games at the Stadium in 1945 and opened the 1945 Negro World Series against the Negro National League’s Homestead Grays on September 13. Cleveland’s 2-1 victory ignited a four-game championship sweep. The second game was at League Park and the final two contests were on the road (Washington and Philadelphia).

The Buckeyes’ only loss when playing at Cleveland Stadium in 1945 was a 2-0 postseason exhibition loss to the Homestead Grays on October 7.

Cleveland Buckeyes contests at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, 1945

- July 16: Cleveland Buckeyes 6, Birmingham Black Barons 2

- July 24: Cleveland Buckeyes 3, Kansas City Monarchs 2

- August 3: Cleveland Buckeyes 4, Chicago American Giants 1

- August 30: Cleveland Buckeyes 1, Memphis Red Sox 0 (first game of doubleheader)

- August 30: Cleveland Buckeyes 2, Memphis Red Sox 0 (second game of doubleheader)

- September 13: Cleveland Buckeyes 2, Homestead Grays 1 (Negro World Series Game One)

- October 13: Homestead Grays 2, Cleveland Buckeyes 0 (exhibition game)6

The Buckeyes played occasional other games there as well, in 1945, 1946, and 1947.

NF Hell

The National Football League in the 1930s was not the same league as in the twenty-first century. Major-league baseball was America’s national pastime while NFL was an afterthought. It was into this quagmire that the Cleveland Rams were born in 1936. They were initially a member of the American Football League in 1936, and joined the National Football League in 1937. Their first game drew 20,000 fans to Cleveland Stadium on September 10, 1937, a 28-0 loss to the Detroit Lions, Because the Stadium “was too big and the rent too high,” the Rams played their home games through 1945 at League Park.7 With a regular-season record of 9-1, the Rams advanced to the 1945 NFL championship game, hosting the Washington Redskins (8-2). The Rams held the championship game at Cleveland Stadium in anticipation of a larger crowd than League Park could accommodate.

According to Rams public relations director Nate Wallack, “Our season-ticket sale was nothing (in) those days. Maybe 200 at the most. We put the (1945) championship seats on sale and immediately we sold 30,000 and we had another week to go before the game. The weather was beautiful. It looked as though we’d sell out the Stadium. Then a blizzard. I mean an awful one. It ended our sales. Now Bill Johns, our business manager, was worried about the field. He wanted to keep it from freezing. He got in his car and set out toward Sandusky, stopping at every farm to buy hay. He wanted to cover the field with it. He bought over 1,000 bales.

“The day of the game the temperature dropped to zero. I sat in the press box and the windows got so steamed we couldn’t see. All the writers had to get out into the stands and freeze. Me too. A water pipe broke in the upper deck and cascading water turned to ice immediately – a frozen waterfall. The fans burned the hay and even the wooden bleacher seats to keep warm. One fan froze his feet and didn’t realize it until he started to walk home after the game. An ambulance had to be called. The game was so exciting, though, the fans stayed to the end. We sold about 35,000 tickets and 29,000 showed.”8

The Rams’ 15-14 victory over the Washington Redskins was the team’s last game in Cleveland. Mickey McBride, a Cleveland taxicab magnate, purchased a franchise for the new All-America Football Conference, to be named after its head coach, former Massillon and Ohio State head man Paul Brown. McBride signed a long-term lease to play home games at the Stadium. Typical of the doom that would frequent Cleveland professional sports teams, the Rams moved to Los Angeles after winning a league championship.

Home Sweet Home

The Stadium entered an unprecedented period of success after the Browns and Indians became its chief tenants beginning in 1946 and 1947 respectively. The Browns won every championship during the four-year history of the All America Football Conference, with three of those wins taking place on the Stadium’s turf. The Indians set a baseball attendance record in 1948, drawing 2,620,627 fans as they won Cleveland’s second – and as of 2024, last – World Series. The Tribe captured Games Three and Four at the Stadium before wrapping up the title at Braves Field in Boston. Noteworthy in the Game Five home loss was a then-World Series-record crowd of 86,288 who had hoped to see the Clevelanders wrap the Series at home.

While the ’50s remained kind to the Browns, the Indians began a slow descent that concluded with a remarkable tumble down the American League standings during the latter decades of the twentieth century. Despite posting a then American League best 111-43 record in 1954, the Indians were swept in the World Series by the New York Giants. The last World Series game played at Cleveland Stadium, on October 2, 1954, was witnessed by 78,102 disappointed fans. The final: New York Giants 7, Cleveland 4.

The Browns entered the NFL in 1950 and promptly captured that season’s title with a 30-28 Christmas Eve victory over the … Rams, who returned to the Stadium for the first time since leaving for Los Angeles five years before. Cleveland appeared in six of the next seven NFL title tilts (going 2-4), including a 1955 championship at the Stadium. The Browns’ 27-0 shutout over the Baltimore Colts at the Stadium on December 27, 1964, remains the last professional championship captured by the Cleveland Browns.

Cleveland Stadium spectacles

Whether it was sports or other events, the Stadium provided a backdrop for a multitude of memorable moments. Ted Williams hit his 500th home run there on June 17, 1960. The Indians’ Len Barker pitched the 10th perfect game in major-league history against the Toronto Blue Jays on May 15, 1981. Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak ended there on July 17, 1941. Bob Feller whiffed a then-record 18 Detroit Tigers on October 2, 1938, from the Stadium’s mound. The first Monday Night Football game ever played pitted the Browns against Joe Namath’s Jets on September 21, 1970, from the Stadium. Four All-Star Games were played at the Stadium.

Cleveland Stadium was also home to 10-Cent Beer Night in 1974 and “The Drive” engineered by John Elway in 1987. During the 1986 AFC Championship game, the Browns had a 20-13 lead over the Denver Broncos with 5:32 left in the contest. Broncos quarterback John Elway drove Denver 98 yards in 15 plays, tying the game with 0:39 remaining. Cleveland lost in overtime on a Denver field goal kick that led the Broncos into the Super Bowl. “The Drive” was born. The Browns again ended up on the wrong end of another playoff game against the Oakland Raiders on January 4, 1981, after quarterback Brian Sipe had a pass intercepted at the east (open) end of the Stadium when a field goal would have won the game. That led to a joke: What do a Billy Graham Crusade and a Cleveland Browns game have in common? Answer: 80,000 fans leaving the Stadium murmuring “Jesus Christ!”

The End

Stadiums are public gathering places, usually for sporting events. What transpires within their walls brings fans together, be it in victory or defeat. Some fans have fond memories of the Cleveland Municipal Stadium. It represents their youth, possibly the site of their first concert, major league, or NFL game.

Over time, the Cleveland Municipal Stadium became known as the “Mistake by the Lake.” After its demolition, the old Stadium’s reinforced concrete was dumped in Lake Erie and used as a barrier reef for fishermen. Like Luca Brasi from The Godfather, it sleeps with the fishes.

Sources

Box scores for all the Cleveland Buckeyes games in 1945 are available on Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Al Silverman, “Landis Lauds Stadium as Perfect for Baseball,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 1, 1932: 17.

2 Silverman.

3 Silverman.

4 National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form, October 1985, Accessed from the Cleveland Stadium Clip File at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

5 Nomination Form.

6 “Defeat Bucks in Last Game, 2-0,” Cleveland Call and Post, October 13, 1945.

7 Hal Lebovitz, “Hal Asks: Remember the Cleveland Rams?” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 20, 1980: 3-8.

8 Lebovitz.