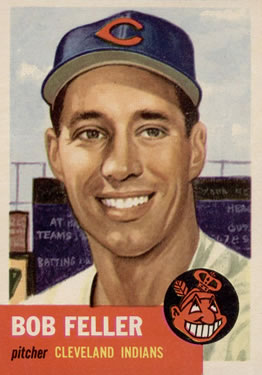

Bob Feller

Bob Feller was a 35-year-old veteran of 15 major-league seasons in 1954 when the Cleveland Indians won 111 games and swept to the American League pennant by eight games over the New York Yankees. His fastball had lost a good deal of its luster and manager Al Lopez had reportedly wanted to release him during spring training. Lopez, however, was overruled by general manager Hank Greenberg, who was worried about fan reaction, particularly since Feller had pitched pretty well in 1953, winning 10 while losing seven.1

Bob Feller was a 35-year-old veteran of 15 major-league seasons in 1954 when the Cleveland Indians won 111 games and swept to the American League pennant by eight games over the New York Yankees. His fastball had lost a good deal of its luster and manager Al Lopez had reportedly wanted to release him during spring training. Lopez, however, was overruled by general manager Hank Greenberg, who was worried about fan reaction, particularly since Feller had pitched pretty well in 1953, winning 10 while losing seven.1

Still, Lopez was reluctant to rely on Feller and sat him on the bench until the third week of the season, when he started Feller in the first game of a doubleheader against the Washington Senators. Feller was gone by the fifth inning but escaped with a no-decision. His next opportunity was not until two weeks later, and this time he made it only until the third inning, again ending with a no-decision as the Indians won. Fortunately, Lopez gave him another chance a week later. This time Feller showed he had something left in the tank, pitching a complete-game 14-3 win over the Baltimore Orioles for the 250th win of his storied career.

After a complete-game loss to the White Sox, Feller got on to a roll, winning six consecutive starts to stand at 7-1 on July 21. Lopez was starting him every six days to great effect. In those six wins he allowed a grand total of only seven runs. His fastball revived to the extent that, if not back to 1940s standards, it was above average. He had developed a sinker to go with his curveball and slider, and sometimes even broke out a knuckleball.2 For the season, Feller finished with 13 victories against just three losses. He threw nine complete games in 19 starts and allowed only 127 hits in his 140 innings of work.

Feller was naturally quite anxious to win his first World Series game, accurately thinking the 1954 World Series would be his last chance.3 Lopez originally penciled Feller to start Game Three against the New York Giants, the first game to be played in Cleveland. When the Indians lost the first two games in the Polo Grounds, however, Lopez opted to start Mike Garcia, who had won 19 games and had the lowest earned-run average in the American League, in Game Three. Feller was hopeful of starting Game Four, but when Cleveland lost Game Three to go down three games to zero, Lopez selected 23-game-winner Bob Lemon to go on short rest. Unhappily for the Tribe, that didn’t work either as the Giants won to sweep the Series.

Feller continued to be perplexed as to why Lopez did not use him at all in the Series, noting that Lopez used seven pitchers, including all the principal starters and relievers but him. In his second memoir, he pointed out that those seven gave up 21 runs in four games.4 His real last chance for a World Series victory, he lamented, had been in 1948, the last time the Indians had been in the Series.5 It was indeed, for the Indians would finish second in both 1955 and 1956, the last two years of Feller’s career.

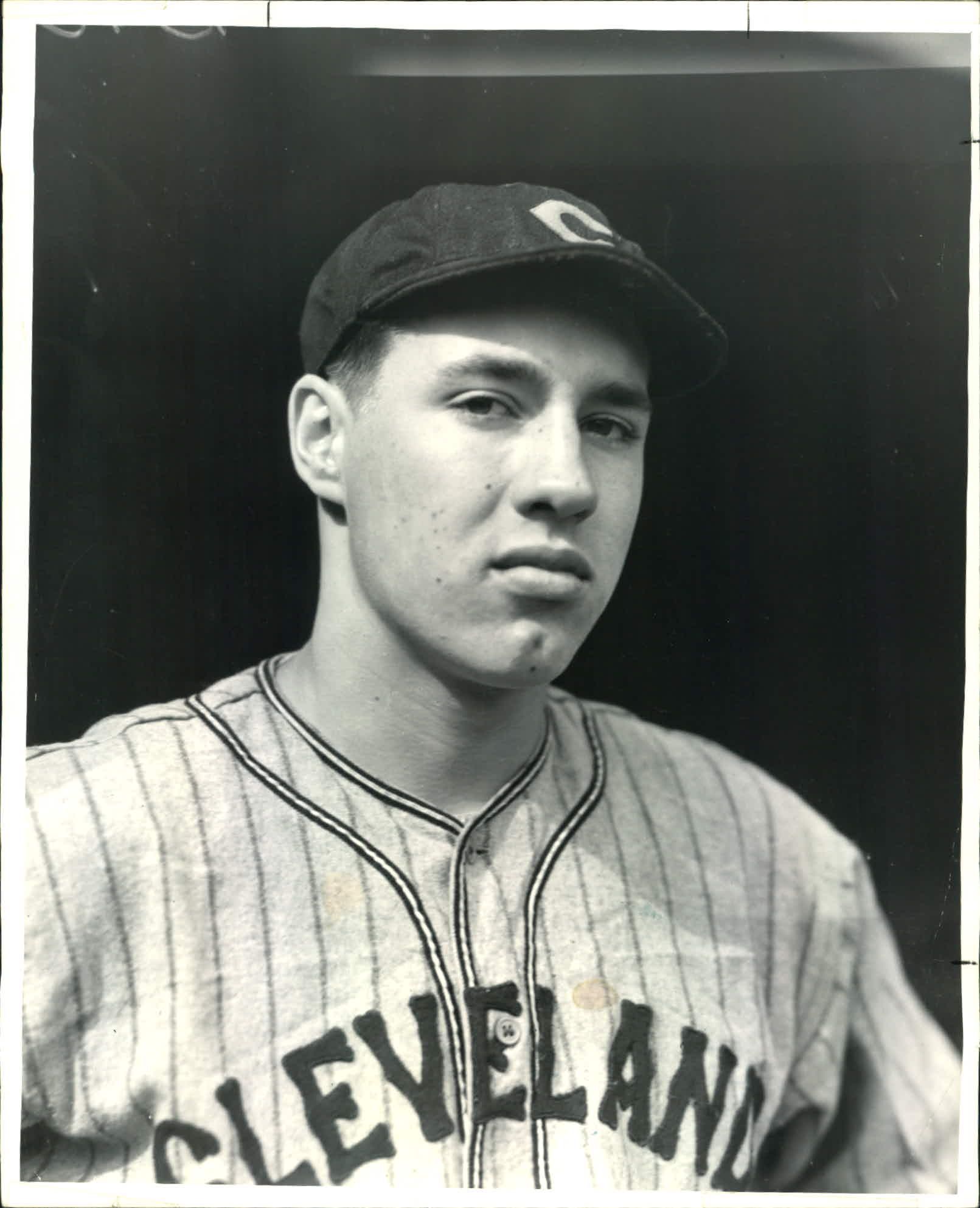

Robert William Andrew Feller was born on November 3, 1918, in Van Meter, Iowa, the first of two children to the former Lena Forrett, a schoolteacher and registered nurse, and William Feller, a farmer. The boy was perhaps the first to be raised by his father to be a major-league star.6 Before little Bobby could walk, his father would roll a ball to him and use a pillow to catch the return tosses.7 From the age of 4 on, playing catch with his father was a daily routine. By the time he was 9, Bobby could throw a baseball more than 270 feet.8 Although he was an excellent hitter and fielder, his father saw his promise as a pitcher and set up arc lights in the barn so that the two could play catch there during cold winter evenings.9

During the summer of 1930, when Bobby was 11, the Van Meter High School team played several games against the elementary school team. Since Feller could throw harder than anyone else, he pitched and more than held his own against the older boys.10 By the fall of 1931, Bill Feller and son took the extraordinary step of building a ballpark on the farm to give local players a place to play and to better showcase young Bobby’s talent. Soon the field, which they called Oak View Park, was hosting games, charging 25 cents admission, and sometimes drawing 1,000 fans.11

Initially, Bobby played mostly shortstop for the Oak View team, batting .321 in the summer of 1933. In 1934, when he was 15, however, he began having exceptional success on the mound, striking out 35 batters in his first 18 innings as a starter for Oak View. He was soon pitching for the American Legion team in nearby Adel as well, with similar results. His batterymate there was often Nile Kinnick, who later won the Heisman Trophy at the University of Iowa before being killed in World War II.12

The following summer, 1935, after reportedly throwing five no-hitters for Van Meter High,13 the 16-year-old Feller graduated to the semipro Farmers Union team in Des Moines, where the competition was tougher and scouts more plentiful. His meteoric rise continued. According to statistics kept by his father, Bob struck out 361 hitters in 157 innings that summer, allowing only 42 hits and compiling an earned-run average of under 1.00.14

In early September Farmers Union traveled to Dayton, Ohio, for the national amateur baseball tournament. Before at least eight scouts, Feller pitched the opening game against Battle Creek, Michigan. He lost, 1-0, but allowed just two hits while striking out 18 batters. Suddenly Feller was besieged with offers that included sizeable bonuses. He couldn’t accept, however, for the fact was that he had secretly signed a contract with Cy Slapnicka of the Cleveland Indians earlier in July.15 A Des Moines semipro umpire had tipped the Indians about Feller and Slapnicka was dispatched to check out the young phenom.16 He was impressed and on July 21 Feller (and his dad since Bobby was 16) signed for a bonus of one dollar and an autographed Indians baseball.17

Feller was to report the following spring to the Fargo-Moorhead Twins of the low-rung Class-D Northern League. While in Van Meter that winter for his junior year of high school, however, he somehow developed a sore arm. The Indians transferred Feller’s contract to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern League, where he was placed on the “voluntarily retired” list while he finished his spring semester of school. After the school year, Slapnicka, whom the Indians had promoted to the equivalent of general manager, had Feller take the train to Cleveland, ostensibly to work in concessions but in reality so that the Indians could monitor the health of his arm.18

After a couple of weeks, Slapnicka arranged for Feller to start two games for the Rosenblums, a fast Cleveland semipro team sponsored by a clothing store. In the second game he struck out 16 while allowing only four hits. Then on July 6, Feller made his professional debut, entering an Indians-St. Louis Cardinals exhibition game in the fourth inning.19 His first pitch was a fastball strike to Bruce Ogrodowski, a rookie catcher. Ogrodowski bunted the second pitch and was thrown out by third baseman Sammy Hale. The second hitter was Leo Durocher, the Cardinals’ shortstop, who attempted to intimidate Feller, yelling, “Keep the ball in the park, busher.” Feller did, striking Durocher out swinging on three fastballs. The third hitter, reserve infielder Arthur Garibaldi, did the same.20

In his three innings of work, Feller gave up an unearned run and struck out eight batters, including Rip Collins, Pepper Martin, and Durocher twice. On his second trip to the plate, Durocher told the umpire, “I feel like a clay pigeon in a shooting gallery.”21 Afterward, a photographer asked Cardinal ace Dizzy Dean it he would pose for a picture with the kid pitcher. Diz responded, “If it’s all right with him, it’s all right with me. After what he did today, he’s the guy to say.”22

Feller was still technically on the Rosenblums roster and started one more game for them, losing 3-2 while striking out 15. Finally, on July 14, the Indians officially put him on the big-league roster, sending him to Philadelphia to join the club there. The 17-year-old’s first official major-league appearance came a few days later, on July 19 in the eighth inning of a game against the Washington Senators in Griffith Stadium that the Indians were losing 9-2. Feller plunked the first batter, Red Kress, in the ribs with a wild curveball. Then, throwing only fastballs, Feller retired the side around two walks on a strikeout and two popups to end his one inning of work.23 His second appearance was six days later, on July 24 in Cleveland. With the Tribe ahead of the Philadelphia Athletics 15-2, manager Steve O’Neill brought the 17-year-old into the game in the eighth inning. In two innings, he gave up three hits and one run while striking out two. He got mop-up duty again two days later in the ninth inning of a 13-0 loss, allowing three hits, a walk, and two runs.24

O’Neill continued to use Feller sporadically in relief before giving him his first start, against the seventh-place St. Louis Browns on August 23 in Cleveland. The fireballer began by striking out Lyn Lary on three pitches, giving up a single to Harlond Clift, and then striking out the number three and four hitters, Moose Solters and Beau Bell. Pitching in 90-degree heat, Feller continued to be overpowering and struck out a total of 15 hitters in a complete-game 4-1 victory, one shy of Rube Waddell’s American League record. He gave up six hits.25

O’Neill knew he had something special on his hands and resolved to start Feller about once a week for the balance of the season. Bob had control problems during his next two starts, losing both and failing to get out of the first inning against the Yankees on September 3. He then defeated the Browns again on September 7, striking out 10 in a complete-game seven-hitter. On the 13th he defeated the Athletics 5 -2 on two hits, but walked nine and allowed seven stolen bases. He was virtually unhittable that afternoon, striking out 17 batters to set the American League record and tying Dizzy Dean’s major-league record.26

Young Feller won two of his last three starts as the 1936 season wound down, with the Indians settling in fifth place with an 80-74 record. For his rookie year, the teenager threw 62 innings in 14 appearances, including eight starts. He posted a 5-3 record, allowing 52 hits, with 76 strikeouts and 47 walks. His 3.34 earned-run average was the best on the club. After the season Feller signed on for a brief barnstorming tour, pitching against Satchel Paige in Des Moines and traveling into the Dakotas and Canada.27

Although one would assume that Feller would not have a worry in the world after his impressive beginning, he in fact did. Pursuant to a complaint from E. Lee Keyser, the owner of the Des Moines Demons, the closest minor-league team to Van Meter, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis was investigating alleged irregularities in his signing by Cleveland, with the threat of declaring him a free agent.28 After summoning Bob and his father to his Chicago office shortly after the end of the season, Landis waited until December to decide that Feller could remain Cleveland property.29

In the meantime, Feller spent the winter finishing high school, taking physics, English literature, American history, and government, before leaving for spring training in New Orleans.30 The Indians and New York Giants annually barnstormed north out of spring training, playing games in places like Vicksburg and Jackson, Mississippi; Thomaston, Georgia; Decatur, Alabama; Little Rock and Fort Smith, Arkansas; Tyler, Texas; and Shawnee, Oklahoma.

Feller first pitched against the Giants in Vicksburg and in three hitless innings struck out six Giants, four in succession. Everyone was impressed except Giants shortstop Dick Bartell, who said, “He’s not so fast. We’ve got several pitchers in the National League who can throw just as hard. I know he isn’t as fast as [Van Lingo] Mungo.” As the caravan moved on, Feller proceeded to strike out Bartell 16 out of 19 times. One sportswriter noted that Bartell went all the way to Fort Smith before he got a loud foul off Feller.31

Overall, Feller had a terrific spring and was dubbed the “schoolboy wonder” in several national publications. Time magazine put him on its April 19 cover, only the second time a baseball player had been so honored.

It all came to a screeching halt on April 24. Feller, in pitching to the first batter in his first start of the year, felt a sharp pain in his elbow when throwing a curveball. He managed to get by only with fastballs for six innings before finally telling manager Steve O’Neill that he had hurt his arm. The Indians sent him to several specialists, most of whom recommended rest. He made national news when he flew home in May to attend his high-school graduation, but on his return to Cleveland was still not ready to take the mound. Finally, in June, Cy Slapnicka sent Feller to A.L. Austin, a chiropractor just a few blocks from League Park, the Indians’ home ballpark. He diagnosed a dislocated ulna bone as the problem, gave Feller’s arm a sudden twist, and pronounced him ready to pitch after one more day’s rest.32

Two days later Feller threw in the bullpen and was pain-free. He returned to action on June 22 with two inning of work and then on July 4 threw four innings against the St. Louis Browns. He was wild but as fast as ever, giving up three runs but only one hit. A week later he pitched an eight-inning complete game against the Tigers, losing 3-2. By late July he was back in the rotation, starting every fifth day. He was 0-4 in his first four starts, but still overpowering most of the time. In August, he threw a 12-strikeout, 10-walk game against the Yankees in Yankee Stadium. Later in the month he struck out 16 Red Sox while walking only four and allowing just four hits.

For the 1937 season, Feller finished 9-7 despite his 0-4 start. In just under 149 innings, he allowed only 116 hits. His 3.39 earned-run average was second on the team to that of Johnny Allen, who won 15 while losing only a single game that season. Feller’s 150 strikeouts were fourth in the league even though he had missed three months of the season.

Incredible as it seems today, especially considering his sore arm, Feller again embarked on a barnstorming trip after the season, pitching against Paige and other top Negro League players. This tour was more extensive and wound through the hinterlands before arriving in Los Angeles.33

So high had been the expectations for Feller that the Associated Press had unfairly named him “flop of the year” for 1937.34 The Indians still had faith in him and backed it with a salary of $17,500 for 1938, right in line with Joe DiMaggio and the highest-paid players on the Indians. New manager Oscar Vitt did not use Feller much in spring training, instead attempting to improve his delivery by shortening his leg kick in bullpen work.35 He started the second game of the season, on April 20 in League Park against the Browns, and pitched the first of 12 one-hitters of his career.36 The only hit was a sixth-inning bunt single that Billy Sullivan barely beat out.37

In late June Feller defeated the legendary Lefty Grove of the Red Sox to run his won-loss record to 9-2 and, on the same day, was named to his first American League All-Star team. Still only 19 years old, he was the youngest player named to the Midsummer Classic. Although he did not appear in the game, won by the National League, 4-1, he was warming up in the bullpen to come in for the bottom of the ninth had the American League been able to tie the score.38

Feller was not as effective after the All-Star break as the Indians faded to third place. The Yankees ran away with the 1938 pennant and as the season wound down, all attention was focused on Hank Greenberg’s run at Babe Ruth’s single-season home-run record of 60. The season concluded on October 2 with Feller starting the first game of a Sunday doubleheader against the Tigers and Greenberg needing two home runs to tie Ruth. Rapid Robert lived up to his name that day, striking out 18 Tigers to set a new major-league strikeout record and steal the thunder from Greenberg, who went without a home run.39 It was almost anti-climactic that Feller lost the game, 4-1.

For the year, his first full big-league season, Feller won 17 and lost 11. His 240 strikeouts led the league as did his hard-to-believe 208 walks, which no doubt contributed to his 4.08 earned-run average.40 All this and Feller was still a teenager. As if 278 innings weren’t enough wear and tear on a 19-year-old arm, Feller took a brief barnstorming trip after the season.41

Feller was given his first Opening Day start in 1939 and defeated Detroit, 5-1, fanning 10.42 Although the Indians were playing about .500 baseball, Feller had won five of his first six starts leading into his May 14 start against the White Sox in Cleveland. That day happened to be Mother’s Day and Feller’s mother was attendance, along with his father and sister. In the third inning, Chicago third baseman Marv Owen sliced a foul ball into the stands, striking Mrs. Feller flush in the face above her left eye and shattering her glasses. Cleveland officials rushed her to the hospital while a visibly shaken Feller managed to complete a 9-4 victory.43

Undaunted, Feller continued to dominate the league, and by late June had put together an 11-3 record. On June 27 he started the first night game in Cleveland history, pitching against the Detroit Tigers. He proceeded to strike out 13 batters and allowed only one hit, a fifth-inning humpback drive off the bat of the recently traded Earl Averill that fell in front of center fielder Ben Chapman.44 By the All-Star break Feller was 14-3 and a shoo-in for the Midsummer Classic. This time he pitched in the game, entering in the fifth inning at Yankee Stadium with a 3-1 lead and holding the National League scoreless in 3⅔ innings of one-hit relief.45

While the Indians finished the season in third place, Feller established himself as the top pitcher in the American League. He led the league with 24 wins, almost 297 innings pitched, 246 strikeouts, 24 complete games, and fewest hits allowed per nine innings.46 Still only 20 years old, he was the youngest starting pitcher in the league and the youngest ever to win 20 games.47 Never one to turn down an extra payday, Feller headed back to California after the season to barnstorm up and down the California coast.48

In 1940 Feller was again the Opening Day hurler, this time with historic results. On April 16 in 40-degree weather in Comiskey Park in Chicago with his mother, father, and sister present, the 21-year-old Feller tossed a no-hitter to win, 1-0. As of 2024 it remained the only Opening Day no-hitter in major-league history.49 Feller continued to dominate as the Indians played themselves into the middle of the pennant race. On June 20 he defeated the Senators, 12-1, to push the club into first place. But while the team was playing well, at the same time Feller and others were revolting against their caustic manager, Oscar Vitt. The press got wind of the revolt and dubbed the team “the Crybabies.”50

In 1940 Feller was again the Opening Day hurler, this time with historic results. On April 16 in 40-degree weather in Comiskey Park in Chicago with his mother, father, and sister present, the 21-year-old Feller tossed a no-hitter to win, 1-0. As of 2024 it remained the only Opening Day no-hitter in major-league history.49 Feller continued to dominate as the Indians played themselves into the middle of the pennant race. On June 20 he defeated the Senators, 12-1, to push the club into first place. But while the team was playing well, at the same time Feller and others were revolting against their caustic manager, Oscar Vitt. The press got wind of the revolt and dubbed the team “the Crybabies.”50

The team nonetheless held first place at the All-Star break. Feller, with a 13-5 record, was named to the All-Star team. He pitched two innings in the game, allowing one run in a 4-0 loss to the National League. In his next regular-season start, on July 12, he nearly had another no-hitter, allowing only an eighth-inning single to Dick Seibert of the Philadelphia A’s.

The pennant race was a tight one and the Indians went into the final series of the season against the Tigers trailing them by two games.51 Feller thus pitched the biggest game of his career to that point on September 27 in the first game of the series. The Tigers, essentially conceding the game and saving their best pitchers for the second and third games of the series, started unknown rookie Floyd Giebel. Although Feller gave up only three hits and two runs on a homer by Rudy York, Giebel pitched the game of his life and shut out the Indians to clinch the pennant for the Tigers.52

For the year, the 21-year-old Feller won 27 games to lead the league, while losing 11. In one of the most dominating performances in history, he also led the league in six other categories, including strikeouts (261), earned-run average (2.61), innings pitched (320⅓), games (43), games started (37), complete games (31), and fewest hits per nine innings (6.9).53 He finished second in the league MVP voting and was named the 1940 Sporting News Player of the Year. Even with his prodigious regular-season workload, Feller could not resist a brief barnstorming tour into Montana and North Dakota before returning home to Van Meter for the winter.54

The Indians’ 1941 spring training was in Fort Myers, Florida, and there Feller began dating Virginia Winther, the daughter of a wealthy Chicago family attending college at nearby Rollins. The Indians had finally fired Oscar Vitt in the offseason, replacing him with Roger Peckinpaugh. The club played well out of the gate and held first place into early June when it began to slump. But Feller had a spectacular first half and by the All-Star break was 16-4. That earned him his first All-Star Game start and he did not disappoint, striking out four and allowing only a single to Lonnie Frey in three innings.55

While the Indians stumbled to a tie for fourth place, Feller again led the American League with 25 wins, against 13 losses. He repeated as the league leader in most major categories including innings pitched (343), strikeouts (260), shutouts (6), games pitched (44), and games started (40).56 Still only 22 years old, Feller now had 107 big-league victories.

He would remain stuck on that number for 3½ years, thanks to World War II. On December 7, 1941, Feller was driving from Van Meter to Chicago to meet with Cleveland officials about his 1942 contract. When he heard on the radio about the attack on Pearl Harbor, he immediately decided to enlist in the Navy and was sworn in at a Navy recruiting office in Chicago on December 9.57

After a couple of weeks back home in Van Meter, Feller reported for basic training at the Norfolk Training Station in Virginia. When he completed basic training, he was given the rank of chief petty officer and became a physical-drill instructor. Beginning in March 1942, Feller played for the Training Station baseball team, playing minor-league clubs and other service teams.58 Feller estimated that the team won 92 of about 100 games played that spring and summer.59

Feller, however, was not content with his light military duty and volunteered for gunnery school after he was turned down for pilot training because he failed a high-frequency-hearing test. He was assigned to the battleship Alabama, stationed in Norfolk,60 where he learned in early January 1943 that his father had died. He was granted a 10-day emergency leave to attend the services. Also, as his father had wished, Feller went ahead with wedding plans and married Virginia Winther in Waukegan, Illinois, before returning to his ship in Norfolk.61

That spring and summer the Alabama was dispatched to the British Home Fleet to escort convoys along the North Atlantic corridor.62 In early August the Alabama was called home to Norfolk and dispatched to the Pacific, traveling through the Panama Canal before arriving at Efate in the New Hebrides Islands on September 14. For the first time since the previous September, Feller was able to play some baseball, pitching for the Alabama’s baseball team and playing first base for the softball team.63

Beginning in November, however, the Alabama went into combat and over the next six months saw action off the Gilbert Islands, the Marshall Islands, Truk, Tinian, Saipan, and Guam. While at sea, Feller occasionally played catch on deck, but in the main was completely away from baseball. In late April and May, the Alabama went for refitting on the island of Majuro, where Feller was again able to pitch for the ship’s baseball team. He threw 47 consecutive scoreless innings at one juncture and continued to work on the slider he’d first developed in Norfolk.64

In early June, the Alabama was out to sea again, participating in the invasion of Saipan. Feller participated in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, one of the most lopsided American victories in the war. In charge of a gunnery crew, he was in the heat of combat and later called the battle “the most exciting 13 hours of my life,” adding, “After that, the dangers of Yankee Stadium seemed trivial.”65 The Alabama continued to see action in and around the Philippines until it finally returning to Seattle for repairs and crew rotation in January 1945. Feller’s combat duties would be over.

After reuniting with his bride,66 Feller received a leave in early February and visited his mother in Van Meter. He was then assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station and in April succeeded Mickey Cochrane as manager of the base’s crack baseball team.67 During the summer of 1945 Feller pitched about 100 innings for Great Lakes, with the highlight coming on July 21, when he threw a 10-strikeout no-hitter before a crowd of 10,000 sailors.68

Finally, on August 21, one week after VJ Day, Feller received his honorable discharge from the Navy. He had served for 44 months and accumulated eight battle stars.69 He was still only 26 years old.

Feller immediately signed a contract with the Indians for the balance of the 1945 season and was treated to a hero’s welcome before his first start, on August 24, just three days after his discharge.70 Before a crowd of more than 45,000 fans, Feller notched a complete-game 4-2 victory over the Detroit Tigers and their ace southpaw Hal Newhouser. Using his new slider with his fastball and curveball, Feller struck out 12 and allowed only four hits. It was his first big-league game in almost four years, but he had announced in no uncertain terms that he was back.71

Feller made eight more starts for Cleveland in 1945, compiling a 5-3 record with a fine 2.50 earned-run average. He struck out 59 in 72 innings, allowing only 50 hits. His best game came on September 19 when, again facing the Tigers, he allowed only a bloop third-inning single by Jimmy Outlaw to finish with the sixth one-hitter of his career.72

Feller was eager to make up some of his lost income from the war73 and organized a monthlong barnstorming trip74 which featured a number of matchups against Satchel Paige and other Negro League stars.75 Then on December 10, Virginia gave birth to the Fellers’ first child, a baby boy they named Stephan and called Stevie.76 In late January Feller organized and held a “free school” in Tampa, Florida, for baseball players returning from the war. More than 180 former players attended the three-week course and 66 eventually signed professional contracts.77

During spring training Jorge Pasquel, a Mexican millionaire who was trying to create another major league south of the border, reportedly offered Feller a three-year contract at $100,000 a year to pitch in his new league. Feller was not anxious to leave the US after two years in the Pacific and turned it down, telling the press, “No chili con carne baseball for me.”78 He opened the 1946 season with a 1-0 shutout of the White Sox. Then, in his fourth start of the year, he threw his second career no-hitter, this time against the New York Yankees in Yankee Stadium in another tense 1-0 win.79 Those starts propelled Feller to one of the greatest seasons of pitching in major-league history. By the All-Star break Feller had 15 wins, half the way to the coveted 30.80 He pitched one-hitters on July 31 and August 8 to bring his career total to eight and break Addie Joss’s major-league record of seven.81 On August 14 he surpassed his personal season strikeout record of 261 and set his sights on Rube Waddell’s major-league record of 349.82

With eight games left in the season, Feller stood at 320 strikeouts. Of the next seven games, he started two on short rest and relieved in another to tie the record at 343 heading in the final game of the season against the Tigers. His opponent was Hal Newhouser, who sported a 26-8 record. A tired Feller didn’t strike out anyone until the fifth inning, but then managed to fan five to break the record and finish at 348 strikeouts.83 For the season, he finished with 26 wins against 15 losses. The sixth-place Indians won only 68 games, meaning that Feller was the winning pitcher in more than 38 percent of his team’s wins.84 He threw an incredible 371⅓ innings in 48 games and 42 starts, 36 of which were complete games. He also led the league with 10 shutouts and his 2.18 earned-run average was the third lowest in the league.85

While putting together this prodigious record, the tireless Feller was organizing an extensive postseason barnstorming trip in which “Bob Feller’s All-Stars” would play 34 games in 27 days. Feller rented two DC-3 airliners for the tour, which started in Pittsburgh and ended in Long Beach, California. Most of the opposition was provided by the “Satchel Paige All-Stars” with Paige and Feller toeing the mound for a few innings in virtually every game. In all the tour covered around 13,000 travel miles and drew an estimated 250,000 fans.86

In January Feller signed a contract with new Indians owner Bill Veeck for 1947, which at $70,000 plus attendance bonuses, was reputed to surpass Babe Ruth’s $80,000 salary as the largest in sports history.87 Although Feller battled injuries in 1947 and elected not to pitch in the All-Star Game because of back pain, he put together another stellar campaign for the improving fourth-place Indians. He pitched two more one-hitters to bring his career total to 10, and finished the season with 20 wins against 11 losses. He led the league in games started (37), shutouts (5), strikeouts (196), and innings (299), and was second in earned-run average (2.68).88 After the season Feller, despite his heavy workload, went barnstorming, again, competing mostly against Satchel Paige and other Negro League stars.89

With the Indians in a pennant race in 1948, Feller, at least for him, struggled during the first half of the season and was only 9-10 by the All-Star break.90 He battled arm fatigue after the break and was inconsistent, sometimes showing his old form and sometimes getting rocked. On October 3, the last day of the season, manager Lou Boudreau sent Feller to the mound against Hal Newhouser and the Tigers with a one-game lead. If the Indians won, they would win the pennant. Feller did not survive the third inning, however, and the Indians lost, 7-1, forcing a one-game playoff with the Red Sox in Boston.91

The Indians won the playoff game, 8-3, behind the pitching of southpaw Gene Bearden, pitching on just one day’s rest.92 The following day, October 6, Boudreau tapped Feller to start the first game of the World Series against the National League champion Boston Braves. He was on his game and didn’t allow a hit until the fifth inning before retiring nine more Braves in a row. He headed into the bottom of the eighth inning locked in a scoreless tie against Braves ace Johnny Sain, who had scattered four hits. In the eighth Feller walked leadoff batter Bill Salkeld, who was replaced by pinch-runner Phil Masi, who was sacrificed to second. With two out, Feller turned and picked Masi off second by at least a foot; the only problem was that umpire Bill Stewart called Masi safe. Unfortunately for Feller and the Indians, Tommy Holmes then singled to left, scoring Masi and sending Feller to a 1-0 defeat.93

Later, with the Indians leading the World Series three games to one, Feller toed the rubber for Game Five back in Cleveland with a chance to close out the Series. He was anything but sharp and struggled to a 5-5 tie into the seventh, when the roof really caved in on him and four relievers. The game ended in an 11-5 defeat. The Indians clinched the Series the next day in Boston but Feller had the ignominy of being the losing pitcher in the only two games the Indians lost in the Series.94

Feller was no better than the third-best pitcher on the crack Indians staff in 1948, finishing with a 19-15 record and a 3.56 earned-run average.95 He did start 38 games, to lead the league, and although his strikeout total dropped to 164, that, too, was first in the league. After the season, Feller did not barnstorm, other than throwing seven shutout innings in an exhibition game to celebrate “Feller Day” in his hometown.96

Named Opening Day starter in 1949, Feller strained a shoulder muscle warming up and lasted only two innings. By the All-Star break, he was only 6-6 and was not named to the AL team for the first time since 1937 (excepting the war years). He finished the season 15-14 with a 3.75 earned-run average as the Indians, beset with injuries, fell to third place. In 211 innings, Feller’s strikeouts fell to 108.97 He improved to 16-11 in 1950, with his ERA dropping to 3.43. At 31, Feller was no longer overpowering, but was still a quality starting pitcher and was again named to the All-Star team.98

Feller started the 1951 season with a vengeance, and on June 30 stood 10-2 with a league-leading ERA of under 3.00. Yankees manager Casey Stengel nonetheless left him off the All-Star team. The day after the team was announced, Feller answered the slight by pitching the third no-hitter of his career, defeating the Tigers 2-1.99 Although Feller was not as sharp in the second half of the season, he still finished 22-8, leading the league in wins for the second-place Indians.100

Unhappily, Feller’s 1952 season was a dud. He finished at 9-13 for the first losing record of his career. He also walked more than he struck out and gave up more hits than innings pitched, both also for the first time. His ERA was an unsightly 4.74 and his disappointing year had a lot to do with the Indians’ second consecutive second-place finish behind the Yankees. Although he had long had his sights set on 300 career victories, Feller was now resigned to falling short of that mark.101

At 34, Feller was able to bounce back in 1953, becoming a serviceable once-a-week starter. He won 10 games, lost seven, and dropped his earned-run average over a run to 3.59 as the Indians again finished in second place behind the Yankees. He continued his success as a weekly starter in the Indians’ runaway 1954 pennant year,102 but in 1955 was restricted to spot starting and long relief. Finishing 4-4, he had a very serviceable 3.47 earned-run average in 83 innings of work. He still showed flashes of his old self, throwing the 12th one-hitter of his career, against the Red Sox on April 16.

Feller was back for more in 1956 and emerged from spring training as the Indians’ fifth starter. But after one ineffective start in April and another in May, he was relegated to the bullpen, where he was used mostly in mop-up duty. The Indians threw a day for him on September 9, honoring him with a new car and various other gifts. President Dwight Eisenhower sent a telegram lauding Feller for his military service and work with charities, which “makes a fine example of American manhood.”103

The final start of Feller’s career was on September 30, the last day of the season. He pitched a complete game against the Detroit Tigers, losing 8-4 and failing to strike out a single batter. For the season, he appeared in only 19 games and threw only 58 innings, finishing 0-4 with a 4.97 earned-run average. Amid much speculation, Feller met on December 28 with Indians general manager Hank Greenberg. When he emerged he announced his retirement to the assembled press.104 He was 38 years old.

Although no one knew it at the time, Feller’s wife, Virginia, had become addicted to barbiturates and amphetamines shortly after the war ended. For the last 10 years of his playing career, Virginia was a constant worry and distraction for Feller. The couple had three sons and Feller had to hire a live-in maid to take care of them. Virginia had several stays in the Mayo Clinic, but couldn’t stem her addiction, which caused insomnia and other behavioral problems as well as stretching the family’s finances. Finally, in 1971 the couple divorced.105

Feller did not slow down upon his retirement as an active player. He got into the insurance business in Cleveland and also joined Motorola as “consultant on youth activities,” crisscrossing the country supporting Little League programs by giving speeches and conducting baseball seminars and camps.106 In August 1957 he appeared on the Mike Wallace Interview program on ABC Television and created controversy by roundly criticizing baseball’s reserve clause.107 He became the first president of the Major League Players Association and helped develop its first pension plan.

In 1958 Feller briefly joined the Mutual Radio Network to help broadcast the Game of the Day.108 He was elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1962, his first year of eligibility, receiving 150 of 160 votes cast.109 After his divorce, Feller was married again in 1974 to Anne Thorpe, a woman he had met in church. He sometimes participated in old-timer’s games and was a frequent guest at sports memorabilia shows around the country. In 1994 the Cleveland Indians erected a 10-foot bronze statue of him at their new Jacobs Field home and in 1995 the Bob Feller Museum, designed by Feller’s architect son, Steve, opened in Van Meter. Feller was still throwing a baseball every day well into his 80s and claimed to have thrown a baseball more often than any man in history.110 The last time he pitched was at an exhibition game in Cooperstown in June 2009, at the age of 90.

Feller was diagnosed with leukemia in August 2010 and died on December 15 of that year. He was 92 years old.

For his 18-year major-league career, Feller won 266 games against 162 losses.111 At 6 feet tall and 185 pounds, he was on the short side for a right-handed pitcher by contemporary standards. Both Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio labeled him the greatest pitcher either had ever seen.112 Although he lost almost four full seasons to service in World War II during the prime of his career, he still led the American League in victories six times and in strikeouts seven times. With his three no-hitters, 12 one-hitters, 279 complete games, and 44 shutouts, he was the dominant pitcher of his generation and one of the greatest of all time.

This biography is included in SABR’s “Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. It also appears in SABR’s No-Hitters book (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Addie, Bob. “Indians Almost Axed Feller!,” Baseball Digest, July 1954.

Berkow, Ira. The Corporal Was a Pitcher: The Courage of Lou Brissie (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009).

Bloodgood, Clifford. “All-Star Double Feature,” Baseball Magazine, September 1942.

Bloodgood, Clifford. “Has Another Walter Johnson Come Along?,” Baseball Magazine, March 1937.

Boudreau, Lou with Russell Schneider, Lou Boudreau – Covering All the Bases (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1993).

Boudreau, Lou with Ed Fitzgerald, Player-Manager (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1949).

Bryson, Bill. “Iowa’s Favorite Son,” in Sidney Offit, ed., Best of Baseball (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1956).

Burr, Harold C. “Indians Cross the Border,” Baseball Magazine, December 1939.

Calhoun, Ralph. “Can Feller Come Back?,” Baseball Digest, August 1945.

Cannon, Jimmy. “Feller’s Legend Bows to Materialism,” Baseball Digest, 1947.

Connor, Anthony J. Baseball for the Love of It – Hall of Famers Tell It Like It Was (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1982).

Cobbledick, Gordon. “Is It True About Bob Feller?,” Sport Magazine, June 1948.

Crissey, Harrington E. Jr., Athletes Away (Philadelphia: Self-Published, 1984).

Dempsey, Jack. “Why Bob Feller Is a Champion,” Liberty Magazine, August 9, 1941.

Dickson, Bill. Bill Veeck – Baseball’s Greatest Maverick (New York: Walker Publishing Co., 2012).

DiMaggio, Joe. Lucky to Be a Yankee (New York: Rudolph Field, 1946).

Fehler, Gene. When Baseball Was Still King – Major League Players Remember the 1950s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2012).

Feller, Bob as told to Edward Linn, “The Trouble With the Hall of Fame,” Saturday Evening Post, January 27, 1962.

Feller, Bob as told to Ken W. Purdy, “I’ll Never Quit Baseball,” Look Magazine, March 20, 1956.

Feller, Bob as told to Ed McAuley, “My Greatest Game – Feller,” Baseball Digest, January 1951.

Feller, Bob as told to Ed Fitzgerald, “Who Says I’m Finished?,” Sport Magazine, April 1949.

Feller, Bob. “The Pitcher and the Preacher,” Guideposts, 1949.

Feller, Bob et. al., “The Players Report Their Doings,” Baseball Magazine, January 1938.

Feller, Virginia, as told to Hal Lebovitz, “He’s My Feller!” Baseball Digest, May 1952.

Flaherty, Vincent X. “Feller Goes to Sea,” Baseball Digest, March 1943.

Gibbons, Frank. “Determined Mr. Feller,” Baseball Digest, September 1951.

Goldstein, Richard. Spartan Seasons – How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1980).

Halberstam, David. The Teammates – Portrait of a Friendship (New York: Hyperion, 2003).

Halberstam, David. The Summer of ’49 (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1989).

Hayes, Gayle. “Fanning With Feller,” Baseball Magazine, December 1938.

Holtzman, Jerome. “An American Hero,” Baseball Digest, December 2000.

Johnson, William H. “The Crybabies of 1940,” in Brad Sullivan, ed., Batting Four Thousand – Baseball in the Western Reserve (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2008).

Katz, Lawrence S. Baseball in 1939: The Watershed Season of the National Pastime (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1994).

Kelley, Brent. The Early All-Stars – Conversations with Standout Baseball Players of the 1930s and 1940s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1997).

Kirksey, George. “When a Feller Needs a Fella,” Baseball Magazine, June 1938.

Lebovitz, Hal. “Mr. Robert, Master Herbie,” in Brad Sullivan, ed., Batting Four Thousand – Baseball in the Western Reserve (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2008).

Lebovitz, Hal. “Bob Feller’s Disappointment,” Sport Magazine, October 1959.

Mansch, Larry. “Hitting Bob Feller,” The National Pastime, Vol. 17 (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1997).

MacFarlane, Paul, ed., Daguerreotypes – The Complete Major and Minor League Records of Baseball’s Immortals (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Co., 1981).

McAuley, Ed. “Feller’s a Whiz Promoting Two,” Baseball Digest, September, 1946.

McKelvey, Richard G. Mexican Raiders in the Major Leagues – The Pasquel Brothers vs. Organized Baseball, 1946 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2006).

Markoe, Arnold, ed., The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives – Sports Figures, Vol. 1, A-K (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2002).

Moore, Joseph Thomas, Larry Doby – the Struggle of the American League’s First Black Player (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2011).

Nason, Jerry. “Feller Slides – Halfway,” Baseball Digest, July 1948.

Oakley, J. Ronald. Baseball’s Last Golden Age: The National Pastime in a Time of Glory and Change (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1994).

Peary, Danny, ed., We Played the Game – 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era, 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994).

Pietrusza, David. Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1998).

Pluto, Terry. Our Tribe – A Baseball Memoir (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999).

Porter, David L., ed. Biographical Dictionary of American Sports – Baseball, Revised and Expanded Edition A-F (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000).

Povich, Shirley. “A Chat with Mr. Feller,” Baseball Digest, August 1946.

Powers, Jimmy. Baseball Personalities (New York: Rudolph Field, 1949).

Schneider, Russell. The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia (New York: Sports Publishing, 2001).

Stockton, J. Roy. “Bob Feller – Storybook Ball Player,” Saturday Evening Post, February 20, 1937.

Szalontai, James D. Teenager on First, Geezer at Bat, 4-F on Deck – Major League Baseball in 1945 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2009).

Thorn, John and John Holway, The Pitcher (New York: Prentice-Hall Press, 1987).

Van Blair, Rick. Dugout to Foxhole – Interviews with Baseball Players Whose Careers Were Affected by World War II (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1994).

Westcott, Rich. Diamond Greats – Profiles and Interviews with 65 of Baseball’s History Makers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988).

Wilson, Nick. Voices from the Pastime (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2000).

Notes

1 John Sickels, Bob Feller – Ace of the Greatest Generation (Dulles, Virginia: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004), 236.

2 John Sickels, op. cit., 239.

3 Bob Feller with Bill Gilbert, Now Pitching – Bob Feller (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1990), 198.

4 Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 201. When asked years later why he had not pitched Feller in the 1954 Series, Lopez responded, “He wasn’t that good of a pitcher anymore.” Wes Singletary, Al Lopez – The Life of Baseball’s El Senor (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1999), 171.

5 Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 198.

6 Frank Deford, “Robert Can Still Bring It,” Sports Illustrated, August 8, 2005: 63. Another early example of a father raising a son to be a star athlete is Colonel Robert Jones, who cultivated his son Bobby from an early age to be a champion golfer. Grantland Rice, “Reg-lar Fellers,” Sport Magazine, September 1946: 18.

7 Donald Honig, Baseball When the Grass Was Real (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc., 1975), 261.

8 John Sickels, 11.

9 Feller’s dad was quoted as saying, “I don’t want him to be a farmer.” Bob Feller, Strikeout Story (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1947), 4; Arthur Daley, Times at Bat: A Half-Century of Baseball (New York: Random House, 1950), 202. The arc lights were used about 15 years before power lines came to the farm. When Feller was 14 or 15 he threw his father a fastball in the barn when he was expecting a curve. The result was three broken ribs for his father. Donald Honig, 263; Fay Vincent, The Only Game in Town – Baseball Stars of the 1930s and 1940s Talk About the Game They Love (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), 37.

10 Strikeout Story, 9.

11 Strikeout Story, 11-13; John Sickels, 15-17; Bob Feller, with Burton Rocks, Bob Feller’s Little Blue Book of Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009), 7. In 1946 after Feller’s second major-league no-hitter, sportswriters asked him who was the greatest figure in his baseball career. “My father,” was Feller’s response. Arthur Daley, 202-03.

12 Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 36; John Sickels, 18-20; Bob Feller, “Bob Feller and American Legion Baseball,” American Legion Magazine, June 1963, 14-15, 45-46.

13 David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman, eds., Baseball – The Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Total/Sports Illustrated, 2000), 346.

14 John Sickels, 22.

15 John Sickels, 24-26.

16 Art Rust, Jr. with Mike Marley, Legends – Conversations With Baseball Greats (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Co., 1989), 38-40.

17 Both are today in the Bob Feller Museum in Van Meter.

18 John Sickels, 30-31.

19 The game was played during the All-Star break. The Cardinals’ 38-year-old manager, Frankie Frisch, reportedly took himself out of the game after watching Feller warm up, saying, “They’re not gonna get the old Flash out there against that kid.” Tom Meany and Tommy Holmes, Baseball’s Best – The All-Time Major League Baseball Team (New York: Franklin Watts, Inc., 1964), 38; Tom Meany, Baseball’s Greatest Pitchers (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1951), 53. For other versions of the Frisch story, see Bob Broeg, Super Stars of Baseball (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1971), 74; Dick “Rowdy Richard” Bartell, with Norman L. Macht, Rowdy Richard – A Firsthand Account of the National Baseball Wars of the 1930s and the Men Who Fought Them (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1987), 190-91.

20 Strikeout Story, 24.

21 Strikeout Story, 25. In his first at-bat, Durocher supposedly took two strikes, dropped his bat, and turned toward the dugout. The umpire said, “You’ve still got a strike left.” “You can have it,” Durocher said, “I don’t want it.” Bob Feller as told to Ken W. Purdy, “Baseball a Game? What a Laugh!” Look Magazine, February 11, 1956: 38.

22 Strikeout Story, 27; Arthur Daley, 201.

23 John Sickels, 38.

24 It was an appearance Feller wanted to forget. He did not mention it in either of his autobiographies. John Sickels, 39.

25 Strikeout Story, 40-42.

26 Adding to his record-setting performance was the fact that his father was in the stands that day. Strikeout Story, 54-58.

27 Timothy Gay, Satch, Dizzy, & Rapid Robert (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 163-67. Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts remembered that Feller came to Springfield, Illinois, that year to throw out the first pitch for the Illinois State Amateur Baseball Championship. Roberts, who was 9 years old, managed to get a Feller autograph but lost it before he got home. Robin Roberts with C. Paul Rogers, III, My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003), 5.

28 Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 41. Although Feller would have been the subject of a huge bidding war if declared a free agent, he was comfortable with the Cleveland organization and very much wanted to stay there. John Sickels, op. cit., 51-52; Franklin Lewis, The Cleveland Indians (New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons, 1949),

195-97; J.G. Taylor Spink, Judge Landis and 25 Years of Baseball, 193-95.

29 During the face-to-face meeting Bill Feller had threatened a lawsuit if Judge Landis declared his son a free agent. David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Co., 1974), 354; William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era – 1945-1951, (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999),

5-6. Landis required Cleveland to pay the Des Moines franchise $7,500 in damages. John Sickels, op. cit., 57; Ed Fitzgerald, “Feller Incorporated,” Sport Magazine, June 1947: 62.

30 Feller’s high-school principal arranged for a tutor and allowed him to graduate with his class if he “could pass the usual tests.” Strikeout Story, 61.

31 Bob Broeg, “No Fireball’s Any Swifter Than Feller’s,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1971: 18; Ed Fitzgerald, 63.

32 John Sickels, 67-71.

33 Timothy Gay, 170-78. The Indians did send trainer Lefty Weisman along to watch over their prized property.

34 John Sickels, 75.

35 Feller initially had trouble holding runners on base with his high leg kick. He was also tipping when he was going to throw to first base with a runner on. Ben Chapman reportedly told Feller he could steal second base on him anytime he wanted and, after doing so, told him how he was tipping his pickoff move. Gene Karst and Martin L. Jones, Jr., Who’s Who in Professional Baseball (New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House, 1973), 299-300.

36 They are listed in Paul MacFarlane, ed., Daguerreotypes – The Complete Major and Minor League Records of Baseball’s Immortals (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Co., 1981), 92.

37 By his own estimation, Feller threw 136 pitches in his one-hitter, striking out and walking six. He also got two base hits and drove in two runs. Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 68-69.

38 Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 78.

39 Greenberg did touch Feller for a double while twice striking out. Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 83-85; Strikeout Story, 143-47; Hank Greenberg and Ira Berkow, ed., The Story of My Life (New York: Times Books, 1989), 106-22.

40 Feller’s wildness in his early years was legendary. In one oft-told incident, Lefty Gomez was batting against Feller late in the second game of a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium. The afternoon shadows were long and when Gomez stepped into the batter’s box, he promptly pulled a cigarette lighter out of his pocket, flicked up a light, and held it in front of his face. The umpire was not pleased and said, “C’mon Lefty, are you trying to make a joke out of the game? You can see Feller just fine.” The quick-witted Lefty responded, “Hell, I can see him. I just want to make sure that wild man out there can see me.” Bill Werber and C. Paul Rogers, III, Memories of a Ballplayer – Bill Werber and Baseball in the 1930s (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001), 99; Elden Auker, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2001), 197; Arthur Daley, 128.

41 Arthur Daley, 148.

42 The Detroit game was the first game of the season. The actual Opening Day in St. Louis, which Feller was to start, was rained out. John Sickels, 84.

43 Mrs. Feller required some stitches but was not seriously injured. Talmage Boston, 1939 – Baseball’s Pivotal Year (Fort Worth: The Summit Group, 1994), 140; John Sickels, 84; Ira Smith, Baseball’s Famous Pitchers (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1954), 284-85.

44 The trade of Averill, who had been openly critical of manager Oscar Vitt, to the Tigers was very unpopular in Cleveland. Strikeout Story, 157-59; John Sickels, 85.

45 Strikeout Story, 159-161; David Vincent, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, The Mid-Summer Classic – A Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 39-43. When Feller struck out Stan Hack in the ninth inning to end the game, 63,000 Yankee Stadium fans gave him a rousing standing ovation. Ed Fitzgerald, 63.

46 Lefty Gomez told the story of batting against Feller and taking the first two pitches for strikes on fastballs he could barely see. When the umpire called strike three on the third pitch, Lefty turned and said, “C’mon. That one sounded a bit low.” Ed Fitzgerald, 64.

47 Feller also tied for the most shutouts with four and was third with a 2.85 earned-run average. He would finish third in the voting for the Most Valuable Player. John Sickels, 87.

48 Commissioner Landis had set forth an edict limiting postseason barnstorming tours to ten days, thus limiting Feller’s West Coast excursion. Timothy Gay, 178-80; Thomas Barthel, Baseball Barnstorming and Exhibition Games, 1901-1962 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2007),

132, 142.

49 John Klima, Pitched Battle – 35 of Baseball’s Greatest Duels from the Mound (Jefferson, North Carolina:, McFarland & Co., Inc., 2002), 63-67; Rich Westcott and Allen Lewis, No-Hitters – the 225 Games, 1893-1999 (Jefferson North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2000), 142-44.

50 The Cleveland fans largely took the side of management and several times threw diapers and baby bottles onto the field during games. John Sickels, 92-98; John Phillips, The Crybaby Indians of 1940 (Cabin John, Maryland: Capital Publishing Co., 1990); William H. Johnson, “The Crybabies of 1940,” in Brad Sullivan, ed., Batting Four Thousand – Baseball in the Western Reserve (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2008), 37.

51 Feller had pitched on short rest several times during September and at one point threw 27 innings in eight days. John Sickels, 99-100.

52 Giebel never won another major-league game. John Sickels, 100-01; Frederick G. Lieb, The Detroit Tigers (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1946), 244; Gene Schoor, Bob Feller – Hall of Fame Strikeout Star (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1962), 132; Brent Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence – Interviews with Baseball Players of the 1940s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2001), 41-50.

53 He also tied for the lead in shutouts with four and reduced his walks to 118 to avoid the league lead in that category for the first time since he became a full-time starter.

54 Feller teamed with Earle Mack and Johnny Mize and played games in Little Falls, Billings, Missoula, and Great Falls, Montana, and in Fargo, North Dakota. Thomas Barthel, 144.

55 Feller promptly picked Frey off first. David Vincent, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, 50-55.

56 Feller also led in hits allowed (284) and walks (194).

57 John Sickels, 115-16; Gary Bloomfield, Duty, Honor, Victory – America’s Athletes in World War II (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2003), 288-89. Feller was already wrestling with whether to enlist or not even before Pearl Harbor. Mike Vaccaro, 1941 – The Greatest Year in Sports (New York: Doubleday, 2007), 270; Strikeout Story, 218.

58 Other professional baseball players on the team included Ace Parker, Sam Chapman, Fred Hutchinson, Jack Conway, Vinnie Smith, and Max Wilson. Strikeout Story, 221.

59 In one game against Wilson, North Carolina, a Class-C team in the Bi-State League, Feller struck out 21 batters. Strikeout Story, 221.

60 Feller requested assignment to the battleship Iowa but apparently there was not room there for everyone from the Hawkeye State. Strikeout Story, 222.

61 Former Indians outfielder Soup Campbell was best man and teammates Lou Boudreau and Rollie Hemsley also attended the wedding. The newlyweds managed a three-day honeymoon in New York City before Feller returned to active duty. John Sickels, 120-22.

62 There Feller recalled playing softball in Iceland at 2 in the morning with the sun still up. He also helped a woman stack her peat moss and milk her cows in exchange for a quart of fresh milk. William B. Mead, Even the Browns – the Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1978), 193.

63 Feller took the lead in constructing a more proper baseball field than the primitive one they found. Led by his pitching, the Alabama’s squad won the 3rd Fleet championship. John Sickels, 123.

64 John Sickels, 125.

65 Strikeout Story, 213.

66 Feller had by now been married almost two years and had spent just five nights with his wife, Virginia. She immediately flew out from Norfolk to reunite with her husband. Strikeout Story, 228; Todd Anton and Bill Nowlin, eds., When Baseball Went to War (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008), 105-09; Todd Anton, No Greater Love – Life Stories of the Men Who Saved Baseball (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2007), 116-33.

67 Although the roster changed continually, the club was stocked with big leaguers like Ken Keltner, Dick Wakefield, Clyde Shoun, Walker Cooper, Denny Galehouse, and Johnny Gorsica. No Greater Love, 230; John Sickels, 128.

68 John Sickels, 129.

69 Strikeout Story, 230-31; According to Feller, although he had enough points, an admiral at Great Lakes was dragging his heels about his discharge. So Feller called the secretary of the Navy and was discharged the next morning, along with 19 others who had enough points. William B. Mead, Even the Browns, 225-26.

70 In pregame ceremonies, Cleveland great Tris Speaker presented Feller with a new Jeep for use back in Iowa. Feller in turn contributed $1,000 to the Press Memorial Fountain Fund. John Sickels, 133. Cy Young was also present for the occasion. Strikeout Story, 232.

71 Feller had pitched an exhibition game in Cleveland for an all-star service team against the American League All-Stars on June 7, losing 5-0. Strikeout Story, 231-32.

72 Strikeout Story, 234-35; John Sickels, 134.

73 Feller believed he had lost about $250,000 due to the war. “The trick,” he told his wife, “was to make it up.” Gene Schoor, Bob Feller – Hall of Fame Strikeout Star, 141.

74 Commissioner Happy Chandler waived the ten-day postseason barnstorming limit to allow ballplayers returning from the service a chance to earn extra money Strikeout Story, 236.

75 Paige and Feller pitched before a crowd of 20,000 in St. Louis and 23,000 in Wrigley Field, Los Angeles, where 10,000 fans were reportedly turned away. Timothy M. Gay, 205; Thomas Barthel, 146.

76 Strikeout Story, 237.

77 Feller recruited former major leaguers such as Dizzy Dean, Bill Dickey, and Lou Fonseca as well as current stars like Joe DiMaggio, Lou Boudreau, Spud Chandler, Eddie Miller, Charlie Keller, Hugh Mulcahy, Rollie Hemsley, and Tommy Bridges to act as coaches. Ed Fitzgerald,, 65; John Sickels, 137-39; William Marshall, 84.

78 Strikeout Story, 238; William Marshall, 49.

79 The game went into the ninth inning a scoreless tie until Frankie Hayes homered off Floyd Bevens for the only run of the game. Feller threw 133 pitches in the game, which ended with Snuffy Stirnweiss on third base for the Yankees in the bottom of the ninth. Strikeout Story, 241-44; John Sickels, op. cit., 140-41; Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 130-32; Rich Westcott and Allen Lewis, 154-55; Don Schiffer, My Greatest Baseball Game (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1950), 75-79; Bob Feller as told to Ed McAuley, “My Greatest Game – Feller,” Baseball Digest, January 1951, 85-87.

80 Feller started the All-Star Game for the American League, which was held at Fenway Park. He pitched three shutout innings, allowing two hits and striking out three, and was the winning pitcher in a 12-0 American League victory. David Vincent et. al., 76-82.

81 Strikeout Story, 245.

82 Strikeout Story, 250; John Sickels, 142; Frederick Turner, When the Boys Came Back – Baseball and 1946 (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1996), 186-89; Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 133-35.

83 Strikeout Story, 253-55. Research later revealed that Waddell had struck out 349 rather than 343 batters, snatching the record back. John Sickels, op. cit., 145. Frederick Turner, op. cit., 204. It has since been broken by Sandy Koufax and Nolan Ryan.

84 The next winningest Indians pitcher was Allie Reynolds with 11 victories.

85 Surprisingly, Feller probably would not have won the American League Cy Young Award had it existed. Hal Newhouser finished 26-9 for the second-place Tigers and led the league with a 1.94 earned-run average.

86 Feller’s club included Stan Musial, Phil Rizzuto, Ken Keltner, Jeff Heath, Charlie Keller, Johnny Sain, Bobo Newsom, and Spud Chandler among others. Paige’s team had Monte Irvin, Max Manning, Buck O’Neil, Sam Jethroe, Hilton Smith, Willard Brown, and Quincy Trouppe. John Sickels, 149-57; Timothy M. Gay, 219-45; Thomas Barthel, 146-52; Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 136-44; Larry Tye, Satchel – The Life and Times of an American Legend (New York: Random House, 2009), 170-75.

87 Feller’s total 1947 income including barnstorming and endorsements may have exceeded $150,000, although high postwar tax rates cut into that amount by as much as two-thirds. John Sickels, 163; Burton Hawkins, “Bob Feller’s $150,000 Pitch,” Saturday Evening Post, April 19, 1947: 25, 148, 170. For Bill Veeck’s account of his salary negotiations with Feller see Bill Veeck, with Ed Linn, Veeck – As in Wreck (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962), 133.

88 In 1947 Billy Goodman, who would win the 1950 American League batting title, was a rookie. He was sent up to hit against Feller and told to make Feller throw him a strike. Goodman later said, “I did better than that. I made him throw me three strikes. I went back and sat down and said to myself, ‘Man, you’re in the wrong league.’ I had never seen anything like that.” Robert W. Creamer, Baseball in ’41 (New York: Viking Press, 1991), 167.

89 The 1947 version of the “Bob Feller All-Stars” included Andy Pafko, Ralph Kiner, Ferris Fain, Ken Keltner, Eddie Lopat, Ewell Blackwell, Jeff Heath, Jim Hegan, and Bill McCahan. It included several games in Mexico but overall was not a financial success. John Sickels, 177-81; Timothy M. Gay, 246-60; Thomas Barthel, 152-55.

90 Feller was nonetheless selected for the All-Star team. He elected not to participate, drawing a firestorm of controversy. John Sickels, 193-94; Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 152-53. American League All-Star manager Bucky Harris was particularly vocal, saying that if he had his way, Feller would never be asked to another All-Star Game. Frank Graham, Baseball Extra (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1954), 143-44. For Feller’s side of the story, see Bob Feller, “When the Crowd Boos!,” American Weekly, July 6, 1952: 1.

91 David Kaiser, Epic Season – the 1948 American League Pennant Race (Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998), 229-30; Russell Schneider, The Boys of Summer of ’48 (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 1998), 62.

92 Gary R. Parker, Win or Go Home – Sudden Death Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2002), 39-75.

93 Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 163-67; Eddie Robinson with C. Paul Rogers, III, Lucky Me – My 65 Years in Baseball (Dallas: SMU Press, 2011), 65; Joseph Reichler, Baseball’s Great Moments (New York: Bonanza Books, 3rd ed. 1983), 32-34; Russell Schneider, 63.

94 Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 170-71; Eddie Robinson with C. Paul Rogers, III, 67.

95 Bob Lemon finished 1948 with a 20-14 record and a 2.82 earned-run average while Gene Bearden went 20-7 with a 2.43 ERA to lead the league.

96 John Sickels, 205.

97 Feller did participate in a brief, unsuccessful barnstorming tour of the West Coast after the 1949 season. John Sickels, 212; Timothy M. Gay, 273-74. The average attendance was about 3,000 but a game in Tijuana, Mexico, attracted a reported 125 fans. Thomas Barthel, 158.

98 In 247 innings, he recorded 119 strikeouts but walked 103.

99 The Tigers’ run was aided by Feller’s throwing error in the fourth inning. That tied the score, 1-1, where it remained until Luke Easter singled in a go-ahead run in the eighth. Afterward Stengel was quoted as saying, “How did I know the guy would pitch a no-hitter? I’m better off dead.” John Sickels, 218-20; Rich Westcott and Allen Lewis, 167-69.

100 In honor of his great season, the Cleveland sportswriters named Feller “Man of the Year.” John Sickels, 222.

101 John Sickels, 231.

102 He often pitched on Sundays, to maximize his still considerable drawing power. Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 210.

103 John Sickels, 247.

104 John Sickels, 248.

105 Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 206-08, 215-17.

106 For example, Feller spoke at the author’s Little League banquet in Casper, Wyoming, in the summer of 1959 and gave an autographed postcard-sized photo to every Little Leaguer in attendance.

107 Wallace took Feller to task since he had been one of baseball’s highest-paid players for many years, but Feller stuck to his guns, noting that the reserve clause very negatively affected the average ballplayer, who averaged only four-plus years in the big leagues. John Sickels, 252-54.

108 In later years, he had a sports radio show in Cleveland and also did some cable-television broadcasting for the Indians. Now Pitching – Bob Feller, 211.

109 John Sickels, 255-56. Feller was elected with Jackie Robinson. They were the first first-ballot inductees since the inaugural Hall of Fame elections in 1939. Feller was the first pitcher elected on the first ballot since Walter Johnson. For Feller’s view of the Hall of Fame in 1962, the year before he was elected, see Bob Feller, as told to Edward Linn, “The Trouble with the Hall of Fame,” Saturday Evening Post, January 27, 1962: 49-52.

110 David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman, eds., 348.

111 Feller was a lifetime .151 hitter with eight career home runs. One was a pop fly that just fell into the right-field pavilion in Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis against Elden Auker. Auker later reported that every time he saw Feller, “that home run gets a little longer.” Elden Auker with Tom Keegan, 120.

112 Robert W. Creamer, 167.

Full Name

Robert William Andrew Feller

Born

November 3, 1918 at Van Meter, IA (USA)

Died

December 15, 2010 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.