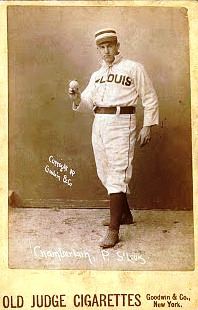

Ice Box Chamberlain

His name was Elton; his friends called him Ed; and baseball writers dubbed him Ice Box, or Icebox, for the ice water that flowed through his veins. According to historian Lee Allen, Elton got his nickname because he was said to possess “austere calm in the face of all hostility by the enemy.” It didn’t matter whether he was facing hostility on the baseball diamond or in a barroom. And he did like his bars, and poolrooms, and the night life.

His name was Elton; his friends called him Ed; and baseball writers dubbed him Ice Box, or Icebox, for the ice water that flowed through his veins. According to historian Lee Allen, Elton got his nickname because he was said to possess “austere calm in the face of all hostility by the enemy.” It didn’t matter whether he was facing hostility on the baseball diamond or in a barroom. And he did like his bars, and poolrooms, and the night life.

Elton was born in Warsaw, New York, on November 5, 1867, the third of the six sons of Carrie and Irving Chamberlain, a veterinary surgeon. Although some baseball references give the spelling of his surname as Chamberlin, contemporary stories showed the ending as –lain.

As a lad Elton moved with his family to Buffalo, and he regarded that city as his hometown. He became a standout baseball player on the sandlots of Buffalo. At the tender age of 16 he decided to follow Horace Greeley’s advice to “Go West, young man!” He sought his fortune playing professional baseball on the banks of the Mississippi in Quincy, Illinois. The youngster did not set the woods on fire there. He appeared in three games for the Quincys, made no hits, and committed three errors in three games. So he decided to try a different direction. He crossed the border and pitched for the Hamilton Clippers in the Canadian League. His win total for the Clippers exceeded his age – 18 wins by the 17-year-old pitcher. He led the league in strikeouts with 189. The next season found him in Georgia, with Macon of the Southern Association. Before the end of the year, he had moved up to Louisville of the American Association, making his major league debut on September 13, 1886, at age 18.

While in the Falls City, Elton became one of three 19th century hurlers known to have pitched ambidextrously. (The others were Larry Corcoran and Tony Mullane.) It would be a bit of a stretch to call Chamberlain ambidextrous. But he did pitch four innings left-handed in the minors and on May 9, 1888, he pitched the first seven innings right-handed and the final two innings as a lefty as the Colonels routed the Kansas City Cowboys 18-6. He seldom pitched left-handed, but he used his dexterity another way. He did not wear a glove, so he could use either hand to throw to a base. As baserunners could never tell with which hand he would throw, he became adept at picking them off.

Chamberlain had a salary dispute with Louisville at the beginning of the 1888 season, and later in the year, the defending AA champion St. Louis Browns purchased him. He went 11-2 for the Browns in the final six weeks of the season, helping them win another pennant. Yet Louisville club president/owner/manager Mordecai Davidson told Sporting Life that September, “I released Chamberlain to the St. Louis club for $4,000, and I am not sorry that I did it. . .I had plenty of pitchers. . .I don’t consider that Chamberlain’s absence has weakened our nine a particle.”

The Browns faced the National League champion New York Giants in the post-season in an event billed as “the world’s championship series.” However, it was viewed by some players and fans as merely a set of exhibition games. Chamberlain was reportedly the St. Louis pitcher whom the New Yorkers feared most. He won two games and lost three as the Giants took the series six games to four.

In 1889 Chamberlain had his best year in the pitcher’s box, winning 32 games for St. Louis. Nevertheless, the Browns suspended him without pay during the last week of June. As soon as Chamberlain was reinstated, St. Louis owner Chris von der Ahe had a row with another top pitcher, Nat Hudson, and suspended him for 30 days, charging insubordination. As the Browns had five pitchers under contract, some observers speculated that the owner suspended his stars in order to save money. At the end of the season Chamberlain demanded an $800 raise, which the Browns refused to give him. So he spent the spring of 1890 hanging around Buffalo poolrooms, until St. Louis sold him to Columbus.

Icebox was an avid boxing fan — but it got him into a couple of scrapes. In February 1891, he pled guilty to aiding and abetting an illegal prize fight in Mayville, New York, and was fined fifty dollars. During that same off-season he won a bet from gambler William Murphy, when Edward Gorman defeated Bob Wright. Chamberlain won a valuable diamond ring from Murphy. Soon thereafter Gorman borrowed the jewel from Chamberlain, and Icebox never saw it again. Chamberlain swore out a warrant, charging Gorman with grand larceny. The fighter was locked up in a Buffalo jail, awaiting trial, but the outcome of the case was not reported in currently available newspapers. Sporting Life wrote, “Chamberlain’s escapade at Buffalo has queered him with Columbus, and he may be released to some other club.”

One trade rumor had Chamberlain being swapped for Pete Browning, but Columbus instead sold him to Philadelphia. After one year there, the American Association folded, and in November 1891, Icebox signed to play with Cincinnati (of the National League) for the 1892 season. That May, Sporting Life quoted an old Browns teammate, Charles Comiskey, with a spin on the nickname. “Elton Chamberlain is the coolest pitcher in the profession. The captain is authority for the statement that whenever Chamberlain perspires his shirt freezes to his skin and he has to take a warm bath before he can get it off.”

Although Chamberlain was in the Queen City for only three years, it was for the Reds that he pitched his two most famous games. Both contests were the second game of a doubleheader and both were against the defending National League champion Boston Beaneaters.

On September 23, 1893, Chamberlain shut out the champs with no hits for a 6-0 win. The game was called because of darkness after the seventh inning. Some sources do not recognize a game of fewer than nine innings as being a legitimate no-hitter; others do. Along with this gem, Chamberlain’s other most memorable outing was the game in which Boston’s Bobby Lowe became the first big-leaguer to hit four home runs in one game. Chamberlain faced Kid Nichols in the second game of a Memorial Day doubleheader on May 30, 1894. Elton gave up two long balls to Lowe in the third inning, one in the fifth, and another in the sixth. In the seventh frame Lowe singled, giving him 17 total bases in the game, a record that stood for over 60 years until it was broken by Joe Adcock in 1954. (The current record holder, Shawn Green had 19.) Chamberlain’s mark of most total bases given up to a batter in one game remains intact.) In a game that had seen 31 runs scored, 33 hits, ten bases on balls, and two hit batsmen, both starting pitchers went the route.

The major leagues had lengthened the pitching distance to 60 feet 6 inches in 1893. Chamberlain did not adjust well to the new distance. He stuck around for two years, but his win totals and strikeouts declined drastically each year and his earned run average skyrocketed. His arm may have been giving out too; Chamberlain had pitched over 400 innings in three of the four seasons from 1889 to 1892.

In 1895, Chamberlain joined the Cleveland Spiders, telling Sporting Life, “I am giving it to you straight that I never felt better in my life and have taken off 13 pounds. Nothing ever pleased me better than my release from the Cincinnatis and if ever I played ball in my life I’ll play it this year. Some people may have their own ideas about my work last season with the Reds, but I’ll tell you truly it was that bum atmosphere coupled with the rankest water in the universe that kept me down. But I’ll tell you once more this is going to be my base ball year and no mistake. I feel out of sight.”

Yet “His Icebergs” did not join the Spiders, claiming that he was supposed to receive one-half of one percent of the purchase money. Sporting Life commented that July, “Chamberlain is not such a good pitcher that he can afford to antagonize the Cleveland Club, and unless there is a speedy coming to terms the indifferent man may find his base ball career cut short, and he will then be able to devote all his time to his string of two trotters.”

Indeed, after 1894 Chamberlain never won another big league game. He joined Warren, Pennsylvania, in the Iron and Oil League in August 1895. The Warren newspapers also called him Iceberg. He spent some time with the San Antonio Missionaries in the Texas Southern League later that same season. Records for neither team are available.

Somehow Chamberlain stayed on good terms with the Spiders and manager Patsy Tebeau, and he was with them again in the spring of 1896. He claimed once more that he’d be back in good form since his arm was now well rested and “good for another five seasons.” However, he lost his only decision for the Spiders, who released him outright in May. He never pitched again in the majors. During the winter meetings that December he was appointed a National League umpire, but that employment did not last.

Reports out of Buffalo in June 1898 said that Chamberlain was thinking about becoming a boxer. It was written that he had signed a contract to fight Jack Baty to the finish for $500 a side. Baty, known as the Black Apollo, was a middleweight from Buffalo, and an experienced professional. The fight evidently never came off. No results of it appeared in the newspapers and an Internet site purporting to list all Baty’s bouts did not include one against Chamberlain.

Icebox tried a comeback with the Buffalo Bisons of the Western League in 1899, but failed to win a game for that franchise, and the papers said, “He is once more following the races.” There were also reports that he might sign with the Minneapolis Millers, but he was not included on their 1899 roster. As late as March 1901, he was still talking of another comeback with the Milwaukee Brewers — player-manager Hugh Duffy said he needed a pitcher — but that did not materialize.

Chamberlain was reputed to have speed, a good curve, and excellent judgment. Three times he won 20 or more big league games in a season, including 32 in 1889. In 1890 he led the AA in shutouts. Three times he finished among the top five in his league in earned run average; three times in winning percentage, and twice in strikeouts. In ten big league seasons he won 157 games, while losing 120 for a winning percentage of .567, with all of his wins coming before his 28th birthday. He was a good hitting pitcher, with a career .203 batting average, and 9 home runs, including a grand slam.

As stated above, Chamberlain was calm when facing hostility in a barroom. For example, an outfielder called Jocko Halligan considered himself to be quite a barroom brawler. One night he thrashed one player and then spotted another potential victim sitting at the bar. Jocko was unaware that Elton was watching his approach in the large mirror behind the bar. Just as Halligan was about to attack, the pitcher wheeled and flattened him with a bar mallet.

Little is known about Chamberlain’s life after baseball, including whether he had a family of his own. Newspapers which had covered his career seldom mentioned him after his retirement. Elton Chamberlain died of colon cancer on September 22, 1929, at the age of 61, in Baltimore. He is the only Chamberlain who was buried in that city’s now-defunct Holy Cross Cemetery.

With additional research by Rory Costello.

February 2011

Sources

Faber, Charles F. Major League Careers Cut Short. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011.

www.la84foundation.org (Sporting Life online)

Boston Globe

New York World

Overfield, Joseph M. “Elton R. Chamberlain,” Nineteenth Century Stars, Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker, eds. Kansas City: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

Syracuse Evening Herald

The Baseball Necrology (www.thebbnlive.com)

Full Name

Elton P. Chamberlain

Born

November 5, 1867 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

Died

September 22, 1929 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.