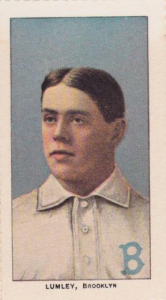

Harry Lumley

In addition to his forte of “long hitting,” Harry Lumley in his prime could “run bases like a thoroughbred” and “more than keep up his end of the game” on defense. “Some of the veteran fans hold him to be the best slugger in the history of baseball,” wrote one commentator in 1907. Ring Lardner described Lumley as one of a dozen left-handed hitters “who hit fly balls or high line drives and who hit them so far that opposing right- and centre-fielders moved back and rested their spinal columns against the fence when it was these guys’ turn to bat.” But the heavy-hitting Lumley also had a tendency to put on weight, and a series of injuries cut short his major league career after only seven seasons.

In addition to his forte of “long hitting,” Harry Lumley in his prime could “run bases like a thoroughbred” and “more than keep up his end of the game” on defense. “Some of the veteran fans hold him to be the best slugger in the history of baseball,” wrote one commentator in 1907. Ring Lardner described Lumley as one of a dozen left-handed hitters “who hit fly balls or high line drives and who hit them so far that opposing right- and centre-fielders moved back and rested their spinal columns against the fence when it was these guys’ turn to bat.” But the heavy-hitting Lumley also had a tendency to put on weight, and a series of injuries cut short his major league career after only seven seasons.

Harry G. Lumley was born in Forest City, Pennsylvania, on September 29, 1880. His family moved to Lestershire (currently Johnson City) in southern-central New York when Harry was a child, and he and Frank Schulte were teammates on the semipro team sponsored by the Endicott-Johnson shoe factory. In 1901 Lumley batted .350 in his professional debut with the nearby New York State League franchise in Rome. After belting a league-leading 8 home runs in 1902 for St. Paul of the American Association, which was not yet under the National Agreement, Harry jumped to Colorado Springs of the Western League for the following year. But when the A.A. entered organized baseball during the off-season, Colorado Springs was forbidden from playing him and he was forced to leave the team after only a dozen games. Lumley spent the rest of 1903 with Seattle of the outlaw Pacific Coast League, leading the fledgling circuit with a .383 batting average. That off-season the P.C.L. joined organized baseball, making the Seattle slugger eligible for the draft, and he was selected by the Brooklyn Superbas.

Harry Lumley burst into the majors with a huge season in 1904, batting .279 in a career-best 150 games and leading the National League with 18 triples and nine home runs. Eighty-two years later, those numbers would earn him SABR’s hypothetical N.L. Rookie of the Year award, but his best was yet to come. After improving his average to .293 with only a minor power dropoff in 1905, Lumley posted a career year in 1906. “The fight between Lumley and Honus Wagner for the leadership in National League batting has been fast and furious,” a sportswriter wrote. Lumley eventually finished at .324, third behind Wagner and Harry Steinfeldt. Although rheumatism and a split finger limited him to 133 games, Lumley slashed 12 triples, third in the N.L., and his nine home runs were second only to Brooklyn teammate Tim Jordan‘s 12. He was Brooklyn’s most popular player, and commentators called him “one of the hardest hitters in the country” and “perhaps the most valuable asset in the Brooklyn organization.” The Superbas refused lucrative offers for their prized slugger from six of the seven other N.L. clubs, including one from the Giants for $10,000.

Lumley was featured prominently in a story Lardner wrote for the New Yorker in 1930 called “Br’er Rabbit Ball,” in which he extolled the virtues of Deadball Era sluggers. The story centered around Ed Reulbach, who’d been assigned by Frank Chance to pitch batting practice to the Superbas because he’d been struggling with his control. “Well, we got to Brooklyn and after a certain game the same idea entered the minds of Mr. Schulte, Mr. Lumley, and your reporter, namely: that we should see the Borough by night. The next morning, Lumley had to report for practice and, so far as he was concerned, the visibility was very bad. Reulbach struck him out three times on low curve balls inside. “I have got Lumley’s weakness!” said Ed to Chance that afternoon.

“All right,” said the manager. “When they come to Chicago, you can try it against him.”

Brooklyn eventually came to Chicago and Reulbach pitched Lumley a low curve ball on the inside. Lumley had enjoyed a good night’s sleep, and if it had been a 1930 vintage ball, it would have landed in Des Moines, Iowa. As it was, it cleared the fence by ten feet and Schulte, playing right field and watching its flight, shouted: “There goes Lumley’s weakness!”

Injuries combined with a “tendency to embonpoint,” as one reporter described Lumley’s proclivity for gaining weight, caused the hard-hitting outfielder’s career to go steadily downhill after 1906. In 1907 he broke an ankle while sliding, ending his season after playing only 127 games. His nine home runs to that point were enough to rank second again in the N.L., and his .425 slugging percentage was the circuit’s third-best, but his batting average plummeted 57 points to .267.

Lumley was named captain in 1908, but the ankle injury continued to bother him and prevented him from getting down to playing weight. He struggled through a season-long slump, made worse by abuse from Brooklyn’s fickle fans. Not satisfied with calling Lumley a “rotten has-been,” one bug hurled the skeleton of an umbrella at the right fielder, and the steel rod stuck in the ground just a couple of feet in front of him. When Harry suffered a charley-horse in his good leg in early-August, President Charles Ebbets offered to send him home—at full pay—for the remainder of the season. The Superbas’ game captain declined, finishing out the year with a dismal .216 average.

Lumley’s perseverance was rewarded during the offseason when Ebbets named him manager for 1909. Actually, the Brooklyn magnate had promised the job in September 1908 to Bill Dahlen, the Superbas’ former shortstop who was then playing for the Boston Doves. After months of delay, the job fell to Lumley when Boston owner George Dovey reneged on his promise to part with Dahlen. The right fielder’s appointment met with derision from some reporters, who did not consider him to fit the Deadball Era stereotype of a brainy and aggressive manager. But within a week of taking over Harry put his own mark on the club by waiving 13 players, including several regulars from 1908’s seventh-place finishers. Appearing in only 55 games as a player in 1909 and batting .250 without a single home run, Lumley guided the Superbas to a 55-98 record, an improvement of 2.5 games and one place in the standings. Nonetheless, Ebbets replaced him with Dahlen before the 1910 season, and the deposed manager appeared in only eight games that year before drawing his release in June.

Lumley settled in Binghamton, New York, near his hometown of Lestershire, serving as player-manager of the New York State League’s “Bingoes” through 1912. Later he operated the Terminal Cafe, a tavern that stood near the current site of Binghamton Municipal Stadium where the Eastern League’s Mets play. Lumley participated in an old-timers’ day at Ebbets Field in 1936 but failing health forced him to give up his restaurant the following year. A widower who never had any children, Harry Lumley died in Binghamton on May 22, 1938.

Note: An earlier version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on Harry Lumley’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York. The author also consulted Ring Lardner’s article, “Br’er Rabbit Ball,” published in the New Yorker (Sept. 13, 1930), reprinted in Some Champions (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1976).

Full Name

Harry Garfield Lumley

Born

September 29, 1880 at Forest City, PA (USA)

Died

May 22, 1938 at Binghamton, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.