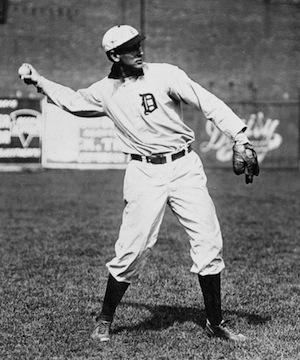

Ed Summers

World Series goats, in one of baseball’s crueler ironies, are more often than not instrumental in their team’s advance into postseason play in the first place. Consider Ed Summers, one of the sport’s first knuckleballers. With Bill Sherdel, Don Newcombe, and Charlie Leibrandt, Summers shares the ignominious record of most losses by a winless World Series pitcher, with an 0-4 record. Yet, before losing two games to the Cubs in the 1908 Series, Summers’s rookie contributions were critical to Detroit holding off the pack in a sensational pennant race. Again in 1909, his two losses to the Pirates followed a fine season at the core of the Tigers’ rotation. Detroit’s dominance ended with the decade, and Summers’s career went into a rapid injury-fueled decline.

World Series goats, in one of baseball’s crueler ironies, are more often than not instrumental in their team’s advance into postseason play in the first place. Consider Ed Summers, one of the sport’s first knuckleballers. With Bill Sherdel, Don Newcombe, and Charlie Leibrandt, Summers shares the ignominious record of most losses by a winless World Series pitcher, with an 0-4 record. Yet, before losing two games to the Cubs in the 1908 Series, Summers’s rookie contributions were critical to Detroit holding off the pack in a sensational pennant race. Again in 1909, his two losses to the Pirates followed a fine season at the core of the Tigers’ rotation. Detroit’s dominance ended with the decade, and Summers’s career went into a rapid injury-fueled decline.

Oren Edgar Summers was born in Ladoga, Indiana on December 5, 1884. He was the last of Mason and Nancy Summers’s eight children. The elder Summers, who served in the 51st Indiana Infantry during the Civil War, made a living as a plasterer.

Ladoga lies some 40 miles west of Indianapolis. In Tecumseh’s War and the War of 1812, white settlers and several Native American tribes contested the region. One of the tribes was the Kickapoo, who departed westward to Kansas soon after the settlers triumphed. During his baseball career, Summers was commonly nicknamed Kickapoo Ed. But the North Carolinians, Marylanders, Kentuckians, and Ohioans in his family tree pushed into Indiana in the same era as the Kickapoo were leaving. This suggests the nickname was an ode to a region, rather than an indicator of Native American heritage.1

Summers pitched for nearby Wabash College in 1903, then joined the semipro Indianapolis Reserves that summer. He began the 1904 season with the Reserves, then was signed by the (Class B) Central League’s Marion Oilworkers. The Springfield Babes of the same league signed Summers for the 1905 season. Having proven “one of the best pitchers in the league” by mid-August, he was sold to the (Class A) American Association’s Indianapolis Indians.2 Summers pitched in a handful of games for the Indians that September, and signed that off-season to join the team for the 1906 campaign.

Early into the 1906 season, however, he was struggling and was sent back to the Central League, this time joining the Grand Rapids Wolverines. Summers spent the remainder of the season with Grand Rapids, proving instrumental in their successful pennant run. That off-season, Indianapolis recalled him, and the upcoming season would be his third attempt to stick with Class A’s faster company.

But, a month into the 1907 campaign, Summers sat mostly forgotten on the Indianapolis bench.

To this point, his career was undistinguished. He was an “elongated juvenile,” standing 6’2”, and weighing a lean 180 pounds.3 Mention of a “whirlwind delivery” may have described his right-handed motion.4 Or it might have been more descriptive of his fastball, for his speed and “inshoots” were mentioned more prominently than his “benders.”

But then, in the summer of 1907, Summers started using his knuckleball with regularity. Frosty Thomas, who pitched for the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers, had taught him the pitch sometime in the previous two seasons.5 Summers may have tutored Eddie Cicotte, who had briefly been his Indianapolis teammate in the spring of 1906.6 Summers’s knuckler was the same as that used by most knuckleball pitchers since: the ball anchored by his thumb and third finger, and gripped by the fingernails of his index and second fingers.7

At first, the pitch was often labelled a “dry spitball,” as it acted similar to spitters thrown with little or no spin.8 The comparison of Summers’s pitch to these spitballs, with a prescient understanding of baseball physics, was detailed in a 1908 newspaper story: “The ball shoots toward the plate in the same way that the spitter does, without twisting or turning in the least. You can count the seams in the ball as it comes toward you. Being pushed against the air without any revolving movement, it floats along with a jerky movement.”9

Summers reportedly could deliver his knuckler from a sidearm or underhand delivery, although most reports reference an overhand delivery.10 He did not use the pitch exclusively, but may have used it increasingly as his career progressed. In 1908, Tiger catcher Boss Schmidt described him using it “fifty times” in a game against Cleveland.11 Two seasons later, with a hardier set of calluses on his first two fingers, Summers noted: “The reason I didn’t resort to it oftener was because it proved an awful wear and tear on my fingers. But I am getting accustomed to it now.”12

With his new weapon, Summers was starring in the Indianapolis rotation by July 1907. In the American League, a tight pennant race was brewing between Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and Philadelphia. In late July, narrowly beating Cleveland to a deal, Detroit purchased Summers, to report after the American Association season concluded in mid-September.

The Tigers soon grew hungrier. A busy stretch run loomed, with clusters of doubleheaders, and manager Hughie Jennings had not found any reliable spot starters to supplement his four-man rotation of George Mullin, Ed Killian, Ed Siever, and Bill Donovan. A couple weeks after the initial deal, Detroit dangled a combination of their unsatisfactory pitching alternatives and additional cash for Summers’s immediate arrival. Indianapolis, however, was also short on pitching. Not until the end of August was an agreement reached. Detroit sent John Eubank to Indianapolis, and Summers was expected to join the Tigers on September 7.

Yet Summers decided not to report to Detroit, instead choosing to stay with Indianapolis. The Tigers won the pennant without him, then were swept by the Cubs in the World Series.

It is difficult to discern what lay behind Summers’s decision. Early in his career he was “as talkative as the Sphinx.”13 He was a non-drinker, and a family man, having married his Ladoga sweetheart Nellie Williams in 1904. Yet Summers could also be “an eccentric character.”14 He had a “trick” left arm, and apparently pitched ambidextrously in moments of his semipro and/or minor league days.15 Later in his career, he sometimes flashed a temper when pitching, and fell victim to illnesses and injuries not always fully appreciated by management.

Despite his failure to report, Detroit sent Summers a contract in early 1908. He signed, and showed well in spring training. On April 16, Summers made his major league debut in Chicago, using “his knuckle ball freely” and holding the White Sox to four hits, as Detroit rallied to win 4-2 in 10 innings.16

The 1908 American League pennant race proved even more dynamic than 1907’s. The Browns, White Sox, Naps, and Tigers dueled continuously, the four teams within 3 1/2 games of each other at the end of August. Detroit fans were afflicted with “pronounced cases of pennantitis,” with attendance surging to a franchise record 436,199, and numerous scoreboards throughout the city drawing ravenous crowds.17

Summers compiled a 24-12 record, and led Tiger starters in victories, innings pitched, and ERA. He particularly feasted upon the sixth-place Athletics. Summers amassed a 7-0 record in his seven starts against Philadelphia, the final two victories coming on September 25 in a doubleheader at Detroit. In the first game, Summers threw a six-hitter as the Tigers won 7-2. In the second, he allowed only two hits in a 1-0, 10-inning victory.

His heroics started a critical 10-game winning streak for the Tigers, in which he claimed another two victories. A final deciding three-game series against the White Sox followed. Summers lost the second game to Ed Walsh on October 5. The next day, Bill Donovan clinched the pennant with a 7-0 shutout.

For the 1908 World Series rematch with the Cubs, Jennings planned a rotation of Killian, Donovan, Summers, and Mullin. The plan quickly went astray when, with a steady rain turning Detroit’s Bennett Field into a swampy mess, Killian fell apart in the third inning of the Series opener on October 10. Summers took over with one out, the bases loaded, and Chicago having already pushed two runs across. A force out and an error resulted in two more runs, and the top of the inning concluded with the Cubs leading 4-1.

Rain plays havoc with a knuckleballer’s grip18, but it soon abated, and Summers pitched well. He proved his own worst enemy in the seventh in failing to adequately cover first, allowing Johnny Evers to reach safely and subsequently score. Nonetheless, the Tigers rallied, scoring twice in the seventh, and three more times in the eighth. Summers began the final inning with a 6-5 lead.

Then the rain returned, and possibly Summers abandoned his knuckler, The Sporting News reporting that he “employed none of the devices with which he had puzzled his opponents in previous innings.”19 Three one-out singles loaded the bases, three more singles won the game for Chicago, 10-6. Jennings earned criticism from some quarters for his “inexplicable failure” to pull the “dazed” Summers from the carnage.20

After the teams split the next two games in Chicago, the series returned to Detroit for Game Five on October 13. Summers started again and pitched well. In the third he issued a pair of two-out walks, for which Harry Steinfeldt and Frank Chance made him pay with run-scoring singles. Mordecai Brown, however, pitched a masterpiece, facing only 29 Tigers. Chicago led 2-0 when Summers was pinch-hit for in the eighth, and pushed another run across in the ninth. The next day Detroit was shut out again, this time by Orval Overall, and the Cubs clinched the championship.

The Athletics, with the pieces of a young infield jelling, proved Detroit’s main competition in 1909. Jennings considered Summers his best weapon against Philadelphia, and started him eight times against the Tigers’ eastern rivals. The final two occurred at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park in a critical four-game series in mid-September. With an extra hundred policemen looking over a teeming crowd of almost 25,000, a pair of throwing errors cost Summers a 2-1 decision to Eddie Plank in the opener. Four days later, Plank again bested Summers, 4-3. These defeats evened Summers’s 1909 performance against Philadelphia at 4-4; the rest of the Tiger staff managed a 4-10 mark versus the Mackmen.

The Tigers left Philadelphia with a two game lead over the Athletics, and staved them off over the next two weeks to clinch their third consecutive American League flag. In his sophomore season, Summers went 19-9 and completed 24 games, placing behind Mullin and Ed Willett in both categories. (A non-decision of note: 18 innings of shutout ball against Washington in a 0-0 tie on July 16.)

On October 8, Mullin lost Game One of the 1909 World Series in Pittsburgh. Donovan won Game Two the next day. For Game Three, on October 11, rain threatened from the dark Detroit skies in a setting reminiscent of 1908’s Game One. At the last moment, Jennings chose Summers over Mullin, “his famous ‘heavy weather’ twirler.”21

Summers became the first pitcher in World Series history not to survive a first inning. On three singles, one walk, one error, and a fielder’s choice, all but one of the eight batters he faced reached base. With the Tigers in a 4-0 hole, Jennings pulled Summers for Willett. Detroit rallied later in the game, but went down to an 8-6 defeat.

Mullin shut out Pittsburgh in Game Four. After Summers reportedly pleaded with Jennings for another shot at the Pirates, the manager gave him the ball for Game Five, back in Pittsburgh, on October 13. Another poor outing resulted. Summers forced a run across in the first on a bases-loaded walk, uncorked a wild pitch in the second to permit another, then the Pirates capitalized on his third inning lead-off walk to Fred Clarke to jump to a 3-1 lead. Again the Tigers rallied, and tied the game at 3-3. But, in the seventh, Bobby Byrne and Tommy Leach hit one-out singles, and Clarke homered to put his team up 6-3. Acting “like a petulant, overgrown kid,” Summers then drilled Honus Wagner in the ribs, who took revenge by stealing second, then took off for third, galloping home after Schmidt’s wild throw sailed into left field.22 Willett relieved Summers in the eighth. Pittsburgh won 8-4. Mullin tied the Series the next day. But Babe Adams won his third game two days later to clinch the championship for the Pirates.

After the World Series, reports surfaced that Summers had been “weakened by an attack of dysentery” before Game Three.23 Jennings’s decision to start him in both games, with other options (particularly Willett) available, earned criticism from many parties, and raised the ire of Tigers president Frank Navin. Nonetheless, Summers did not beg off from the opportunities, and responded with subpar performances.

Independent of the four defeats Summers absorbed, Detroit lost two-thirds of the other dozen World Series games they played 1907-1909. Contemporary Series reporting judged Chicago’s and Pittsburgh’s infield play superior to Detroit’s. Both the Cubs and Pirates ran against Tiger catchers, particularly Boss Schmidt, with savage abandon.24 Jennings was not baseball’s only gifted motivator to be out-generaled in a tight, final competition. In short, the Tigers may have less under-achieved by losing three World Series, as they over-achieved by winning three spirited pennant races.

In 1910, Philadelphia decisively ended Detroit’s run, with the Tigers falling out of the race by mid-July. Ed Summers was, at 25, in decline. Since early 1909, his rheumatic knees required game-day wraps; in 1910 they limited him to 220 1/3 innings, over which he compiled a 13-12 record. Teams were also adapting to his game. The Pirates, in the 1909 World Series, provided one strategy by simply laying off his knuckleballs. The Athletics, observing the fast-working Summers peevishly snapping at a young Tiger catcher to return balls more quickly to him, embarked upon a course of deliberate stalling between pitches. Eddie Collins: “We had less of a problem with Summers after that.”25

Detroit began the 1911 season with a sizzling 21-2 start. Summers was on the shelf with assorted ailments, however, and Jennings was “frothing at the mouth” with his pitcher’s inability to return to action.26 Finally, on May 30, Summers made his 1911 debut, besting Cleveland in ten innings, 3-2.

Philadelphia was charging hard by then and, in each of the five remaining series between the clubs, Summers started the opening game. One final great outing resulted: in the first game of a July 28 doubleheader, in front of 33,000 at Shibe Park, Summers and Chief Bender matched shutout ball for 10 innings before Collins drove Bender home with the winning run in the 11th. Philadelphia soon sprinted past Detroit, and the Tigers eventually finished 13 1/2 games back in second place. Summers broke even at 11-11 over 179 1/3 innings, with a 3.66 ERA.

In 1912 Summers’s arm died in spring training. For the second straight season, he didn’t pitch until Memorial Day, and then unimpressively. On June 15, Detroit waived him, along with Mullin. Neither was claimed, and the Tigers brought back both pitchers. On June 21, Summers didn’t escape the first inning versus Cleveland. After a few more weeks of inactivity, the Tigers released him to Providence. With his arm still unresponsive, Kickapoo Ed returned to Ladoga.

Summers served as the town marshal, umpired a bit, and pitched a little semipro ball. In 1916 he coached the Wabash College baseball team to a 12-6 mark. In 1918 the Summers family moved to Indianapolis, where Ed went to work for Prest-O-Lite as a welder. For three decades he stayed in this role, “a quiet, unassuming fellow with an easy smile and a keen sense of humor,” whose “fellow workers’ only complaint about him was that he was reluctant to talk about his previous career.”27 Ed Summers passed away on May 12, 1953, several weeks after suffering a paralytic stroke. He was buried in Ladoga Cemetery. His wife Nellie, daughter Agatha, son Arthur, and four grandchildren survived him.

Sources

Research materials towards Summers’ 1916 coaching provided courtesy of the Robert T. Ramsay, Jr. Archival Center at Wabash College, Crawfordsville, IN. In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Summers’ player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following sites:

Notes

1 Summers himself apparently never spoke of a specific Kickapoo heritage. Newspapermen did not refer to a Kickapoo heritage, or use general terms of racial identification, as they did with Chief Bender and his Chippewa heritage.

2 “Victory Was Easy,” Grand Rapids (MI) Press, August 25, 1905, 6.

3 “Willow Wielding Wins Final Game,” Fort Wayne (IN) Sentinel, June 1, 1905, 6.

4 “Fans Wept With Joy,” (Canton, OH) Repository, September 15, 1906, 3.

5 Joe S. Jackson, “Much-Discussed ‘Knuckle Ball’ Now Credited to Thomas, A Former Tiger,” Detroit Free Press, March 24, 1908, 8.

6 For an exhibition game with Cicotte relieving Summers, see “Wabash Collegians Easy for Hoosiers,” Indianapolis News, April 13, 1906, 22.

7 W.W. Bingay, “Summers’ Surprise,” Sporting Life, May 16, 1908, 13.

8 For the first such mention found by the author, see “Through the Knot-Hole in the Left-Field Fence,” Indianapolis News, June 26, 1907, 10. For spitball behaviors, see Mike Lackey, Spitballing: The Baseball Days of Long Bob Ewing (Wilmington, OH: Orange Frazer Press, 2013): 122-124

9 “Twirlers Show How It Is Done,” (Washington, DC) Evening Star, April 19, 1908, 60.

10 Paul H. Bruske, “Detroit Dotlets,” Sporting Life, March 28, 1908, 3.

11 Bingay, “Summers’”

12 “Knuckle Ball a Puzzler,” Ann Arbor (MI) Press, May 4, 1910, 5.

13 “Kickapoo Summers No Longer a Sphynx,” Grand Rapids (MI) Press, June 28, 1909, 6.

14 “Kick Flunked Out,” Grand Rapids (MI) Press, September 14, 1907, 8.

15 Edward W. Cotton, “From Left to Right,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, August 15, 1954, 13. This article, with his widow’s recollections and a photo of (seemingly) Summers in a Tiger uniform warming up as a lefthander, suggests he indeed did pitch from both sides. But during his playing days there seems to be no specific reporting of this. One suspects then, that it likely occurred early on in his minor-league career, or limited to some relaxed semipro moments.

16 Joe S. Jackson, “Ed Summers Pitches Tiges to Ten Inning Victory Over Sox,” Detroit Free Press, April 17, 1908, 1.

17 Joe S. Jackson, “Grand Roadsters,” Sporting News, July 23, 1908, 1.

18 R.A. Dickey, a century after Summers, on rainy day knuckleballs: “It’s like throwing water balloons.” Andrew Keh, “Dickey Picks Bad Day to Have a Bad Start,” New York Times, April 18, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/19/sports/baseball/dickeys-run-of-quality-starts-for-mets-ends-in-atlanta.html, accessed May 18, 2014.

19 A.J. Flanner, “Tigers Won Third,” Sporting News, October 15, 1908, 1.

20 Ibid; Francis C. Richter, “Great 1908 Battle of the Major Giants,” Sporting Life, October 24, 1908, 4.

21 “Maddox is Pittsburg’s Pitching Choice in Third Battle with the Tigers,” Wilkes-Barre (PA) Times-Leader, October 11, 1909, 1.

22 “Pitching Decided World’s Series in That Department Pittsburg Had Edge on Detroit Clarke Showing Better Judgment,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 18, 1909, 6.

23 Francis C. Richter, “Great 1909 Battle of the Major Giants,” Sporting Life, October 23, 1908, 3.

24 Only four times has a team stolen more than a dozen bases in a World Series. The Braves stole 15 (and were caught three times) in 1992 against the Blue Jays. The Cubs stole 15 (caught five times) in 1907, 15 again (caught eight times) in 1908, and the Pirates stole 18 (caught six times) in 1909.

25 Norman Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007), 473.

26 Paul Hale Bruske, “Base Ball Stars Fade,” Sporting Life, June 29, 1912, 1.

27 “Eddie Summers Now Pitching,” Linde Notes (published date unknown, from Baseball Hall of Fame Library file); Cotton, “From Left to Right.”

Full Name

Oron Edgar Summers

Born

December 5, 1884 at Ladoga, IN (USA)

Died

May 12, 1953 at Indianapolis, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.