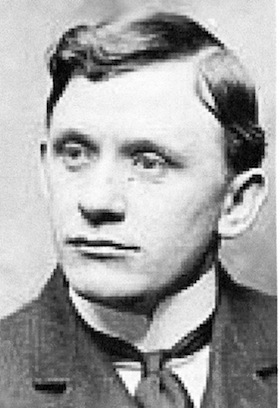

Jimmy St. Vrain

Newly recruited from the Pacific Northwest League, boyish left-hander Jimmy St. Vrain pitched capably for the Chicago Cubs in early part of the 1902 season. Plagued by poor defensive support – more than one-third of the runs surrendered by St. Vrain were unearned – he posted a hard luck 4-6 record, with a fine 2.08 ERA, in 12 appearances. By mid-June, however, St. Vrain was odd man out on the overstocked Cubs staff, prompting manager Frank Selee to option the youngster to Memphis of the Southern Association – but not before he had signed St. Vrain to a Chicago contract for 1903. Despite his youth, coveted left-handedness, and creditable 1902 audition, St. Vrain was never recalled by the Cubs. Nor would he receive a big-league shot elsewhere. The major-league career of Jimmy St. Vrain was over at reputed age 19. Not even a 25-win season pitching for West Coast teams in 1903 could secure St. Vrain a second chance.

Newly recruited from the Pacific Northwest League, boyish left-hander Jimmy St. Vrain pitched capably for the Chicago Cubs in early part of the 1902 season. Plagued by poor defensive support – more than one-third of the runs surrendered by St. Vrain were unearned – he posted a hard luck 4-6 record, with a fine 2.08 ERA, in 12 appearances. By mid-June, however, St. Vrain was odd man out on the overstocked Cubs staff, prompting manager Frank Selee to option the youngster to Memphis of the Southern Association – but not before he had signed St. Vrain to a Chicago contract for 1903. Despite his youth, coveted left-handedness, and creditable 1902 audition, St. Vrain was never recalled by the Cubs. Nor would he receive a big-league shot elsewhere. The major-league career of Jimmy St. Vrain was over at reputed age 19. Not even a 25-win season pitching for West Coast teams in 1903 could secure St. Vrain a second chance.

More than a century later, no obvious cause for the lack of major-league interest in the pitcher (like an arm injury, excessive drinking, disciplinary issues, etc.) presents itself. But to speculate, the professional fate of Jimmy St. Vrain may have been dictated by circumstances beyond his control: his true age and a diminutive stature. Until quite recently, the St. Vrain entries in baseball reference works, from the 1951 Turkin and Thompson Official Encyclopedia of Baseball to a present-day authority like Baseball-Reference, would not support this hypothesis.1 Such works provided a June 6, 1883, date of birth for St. Vrain, and list his physical stature as 5-feet-9 and 175 pounds, a size comparable to that of Jack Taylor, Mordecai Brown, and other pitching contemporaries. But these data are either wrong or suspect. The St. Vrain birth year long provided in baseball reference works falls into the erroneous category. In fact, it is impossible, as Jimmy’s father (Marcellin St. Vrain, 1815-1871) and mother (Elizabeth Jane Murphy St. Vrain, 1832-1880) were both dead years before Jimmy’s putative birth in 1883. Young Jimmy St. Vrain was, in fact, already in his early 30s when sent back to the minors in 1902. Unlike his true 1871 date of birth – provided in various St. Vrain family histories posted online2 – the physical stature of our subject is not susceptible to definitive calculation, his size not having been expressly delineated in contemporaneous baseball reporting. But when not described in the press as “young” Jimmy St. Vrain, the hurler was often called “little” Jimmy St. Vrain, a “little sawed-off specimen of southpaw humanity,”3 who was “no bigger than a cake of soap.”4 Again, while ultimately unknowable at this late date, perception of St. Vrain as an undersized and aging pitcher may well have proved an insuperable obstacle to a major-league encore.

Jimmy St. Vrain was descended from French aristocrats dispatched to America in the late 1700s to administer French possessions west of the Mississippi River. After the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the family settled in St. Louis, where their surname, originally the imposing de Hault Delassus de St. Vrain, was shortened to St. Vrain. Jimmy’s uncle Ceran St. Vrain (1802-1870) ventured farther west into the wilderness to trade in furs. In time, he established a trading outpost in Colorado that came to be known as Fort St. Vrain. Around 1835 Ceran sent for his younger brother Marcellin (born October 14, 1815, in Spanish Lake, Missouri), who took over supervision of Fort St. Vrain. One family history describes Marcellin as small, charming, an avid outdoorsman, and a “devil with women.”5 Depending on which family history is credited, Marcellin St. Vrain took either one or two teenage Indian women related to the notable Sioux Chief Red Cloud as his consort(s), fathering anywhere between three and five children. Sometime in the late 1840s circumstances (about which, again, family histories differ) prompted Marcellin to abandon Fort St. Vrain and his Indian wives/children and return to the St. Louis area. On June 29, 1849, Marcellin married 17-year-old Elizabeth Jane Murphy of Florissant, Missouri. From then on, Marcellin busied himself operating a St. Louis County flour mill and keeping his new wife pregnant. Over time, Elizabeth Murphy St. Vrain would bear ten children.

On March 3, 1871, Marcellin St. Vrain died, reportedly by his own hand. At the time of his death, wife Elizabeth had already borne eight children, and was pregnant once again. On June 6, 1871, she delivered twins: James Marcellin St. Vrain and Elizabeth Zelena St. Vrain.6 In the 1880 US Census, Jimmy’s mother is listed as E.J. Powell, and living in Jasper, Ralls County, Missouri, at the home of her 24-year-old son W.E. (actually Eugene William) St. Vrain. A number of Elizabeth’s other children – L.A. (Leona Ann) St. Vrain, age 15; P.A. (Paul Augustin) St. Vrain, age 12; James M. St. Vrain, age 9; and E.Z. (Elizabeth Zelena) St. Vrain, age 9 – are also listed as members of the household. On December 4, 1880, Elizabeth Murphy St. Vrain died, and was subsequently laid to rest besides her husband in Salem Cemetery in the town of Center, Missouri. Upon this event, Jimmy and the younger St. Vrain children presumably either stayed with brother Eugene in Jasper, or were then taken in by other older siblings. In any event, Jimmy St. Vrain disappears from view for the next 18 years, his movements and activities lost to time.

According to a 1937 death notice published in the Montana Standard, Jimmy St. Vrain came to Butte, Montana, in 1898, finding work as an electrician.7 Another published report described St. Vrain as an attendant in a Butte barber shop.8 Whatever the case, sometime before he reached Montana, Jimmy had developed into a left-handed pitcher as well. His first local playing engagement was for a semipro team sponsored by the Butte Reduction Works. In 1899 he played for the semipro Butte & Boston Railroad nine. The following year, Jimmy entered Organized Baseball, joining the Butte entry in the four-team Montana State League.9 The highlight of the 1900 season, however, occurred off the field. At the conclusion of an August 16 game against Helena, St. Vrain hurriedly excused himself from the grounds and changed into a black suit. It was his wedding date. That evening, he and 17-year-old Frances (Fanny) Barnes, “an ardent admirer of the national game” originally from Omaha, were quietly wed.10 The couple remained together for the next 37 years, but their union appears to have been childless.

In 1901 St. Vrain signed with the Tacoma Tigers of the Pacific Northwest League, but his tenure there got off to a rocky start. After a dominating preseason exhibition-game performance against a team from Victoria, British Columbia, St. Vrain was taken ill. The diagnosis was smallpox, for which Jimmy was obliged to spend the next six weeks quarantined in the “pest house.”11 Once back in action, St. Vrain was outstanding, recording a league-leading 299 strikeouts and being deemed by an Eastern newspaper “the second best” pitcher in the PNL.12 During the offseason he remained in Tacoma and again found work as an electrician. With the aggressive player-recruitment efforts of the upstart American League working greatly to ballplayer advantage, St. Vrain also spent the winter entertaining offers for the 1902 baseball season.

In February 1902 the sports press announced that Jimmy St. Vrain, “a heady youngster with all kinds of curves and speed,” had signed with the National League Chicago Cubs.13 Soon thereafter, it was reported that “little Jimmy St. Vrain,” unnerved by the 40-odd prospects headed for the Chicago spring-training camp, had decided to return the $100 advance money doled out by Chicago and remain with Tacoma.14 According to Sporting Life, St. Vrain (who would turn 31 during the coming season) “is a youngster with much to learn yet, and a season under a competent manager like [Tacoma’s Jay] Andrews, he thinks, will put him in a position where he can enter the big leagues without fear.”15 Chicago, however, was not easily discouraged. And ultimately “a persuasive letter from [Cubs] manager [Frank] Selee induced [St. Vrain] to change his mind and make an attempt to break into faster company.”16

In February 1902 the sports press announced that Jimmy St. Vrain, “a heady youngster with all kinds of curves and speed,” had signed with the National League Chicago Cubs.13 Soon thereafter, it was reported that “little Jimmy St. Vrain,” unnerved by the 40-odd prospects headed for the Chicago spring-training camp, had decided to return the $100 advance money doled out by Chicago and remain with Tacoma.14 According to Sporting Life, St. Vrain (who would turn 31 during the coming season) “is a youngster with much to learn yet, and a season under a competent manager like [Tacoma’s Jay] Andrews, he thinks, will put him in a position where he can enter the big leagues without fear.”15 Chicago, however, was not easily discouraged. And ultimately “a persuasive letter from [Cubs] manager [Frank] Selee induced [St. Vrain] to change his mind and make an attempt to break into faster company.”16

Jimmy St. Vrain, “short of stature but with plenty of speed and benders,”17 performed well in spring camp and was inserted into the Chicago rotation at the start of the season. On April 20, 1902, he made his major-league debut before an overflow crowd of 13,000 spectators jammed into Cincinnati’s newly refurbished League Park. St. Vrain pitched well – a complete-game six-hitter – but lost 2-1, two bloop RBI singles spelling the difference. His second start, a week later, produced a similar result: a complete-game 2-0 loss to Pittsburgh, with both Pirates runs being unearned. On May 9 Jimmy broke into the win column in grand style, posting a 5-0 shutout of the New York Giants, allowing only four hits while striking out seven. Two days later the Chicago Tribune published a photo of St. Vrain with the caption “Manager Selee’s Good Left-Hand Pitcher.”18 On May 12 the ill luck that pursued St. Vrain struck again. He dropped a 2-0 decision to Brooklyn, with both runs charged against him being unearned.19

In the next few weeks, St. Vrain managed to raise his record to 4-5, but his position on the roster was threatened by the June signing of right-hander Carl Lundgren, the University of Illinois ace whom Frank Selee had long had his eye on. As noted back in Montana, “Jimmy St. Vrain’s tenure … on manager Selee’s pitching staff depends on whether Lundgren, the new pitcher from Illinois University, makes good.”20 Lundgren promptly satisfied his part of the equation, posting a gritty 7-5 complete-game win over St. Louis in his major-league debut. St. Vrain then fulfilled his, sealing his fate by yielding six quick runs to Boston several days later. On June 20 Chicago released “James St. Vrain, the miniature southpaw, to the Memphis club of the Southern league.”21 The demotion, however, was viewed as only temporary, “for St. Vrain, before leaving for the South, signed his name to a Chicago contract for next season. St. Vrain knows his weakness, that of inexperience, and consented readily to Selee’s proposition.”22 But unbeknownst to all parties, the major-league career of Jimmy St. Vrain had now run its course. His lifetime record was frozen at 4-6, with a 2.08 ERA in 12 appearances. In 95 innings pitched, he had yielded 88 hits, striking out 51 while walking 25.

Jimmy reported to Memphis on June 23. His time there would quickly turn into a nightmare, a maelstrom of litigation, injunctions, forfeited games, and other turmoil that would culminate in his placement on Organized Baseball’s ineligible list, and the near dissolution of the Southern Association. The engine of all this unpleasantness was competing claims upon St. Vrain’s services. When Chicago released St. Vrain to Memphis, the Tacoma Tigers asserted a reserve clause-based right to recoupment of the pitcher. Memphis boss Charley Frank ignored the Tacoma claim and promptly put St. Vrain in harness for the Egyptians. When the dispute was placed before the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, the governing body of minor-league baseball sided with Tacoma, and ordered Frank not to play St. Vrain. Frank ignored that order, as well. In time the situation degenerated into a battle of dueling lawsuits and injunctions, punctuated by player ineligibility decrees, game forfeits, franchise suspensions, the midseason resignation of league President John Bailey Nicklin, and the near disbanding of the Southern Association.23 As the chaos continued, St. Vrain might pitch, or be confined to the bench, or be barred from admission to the ballpark, depending on the venue. When he was permitted to work, Jimmy demonstrated what the fight over his services had been about, going a sterling 12-4 in 17 games for Memphis.

In January 1903 St. Vrain paid the face-saving $100 fine that had been imposed by the beaten-down minor-league establishment. He was thereupon restored to good standing. 24 But the Southern Association fracas appears to have inflicted an irreparable injury upon St. Vrain’s prospects with the Chicago Cubs. Despite the contract that he had signed the previous June and his fine Memphis record, Jimmy was not invited to the Cubs’ spring camp. Cast adrift, he signed with the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, for whom he proved a bust. With the St. Vrain record standing at 0-6, Minneapolis released him in late May.25 Fortunately for Jimmy, Tacoma, now a member of the Class A Pacific National League, held no hard feelings about the previous year, and re-signed him.26 St. Vrain then repaid the club’s goodwill, going 14-7 before the Tacoma franchise disbanded on August 16. Jimmy finished his 1903 odyssey with the Seattle Siwashes of the [then] independent Pacific Coast League, going 11-9 before the grueling 200-plus game PCL season came to a close. In 50 games spread across three leagues, the now 32-year-old St. Vrain amassed a 25-22 record for the year.

The 1904 season was St. Vrain’s last as a top-flight minor-league performer. He went 18-13, with a 3.16 ERA over 302 innings pitched, for a newly constituted Tacoma Tigers franchise that won the PCL crown. Unhappily, Jimmy seems to have gotten into a late-season dispute with Tacoma manager Mike Fisher. The following season, St. Vrain signed with a PCL rival, the Portland Giants. The parting with Tacoma was the subject of a rare display of disdain by the normally genial hurler. When asked the following spring about the management situation on his former club, St. Vrain stated, “Mike Fisher is the limit. Charlie Graham is the man who ought to be the manager of the Tacoma team for he does all the work, and Fisher claims all the glory. You may think that I am sore at Tacoma because I was released last fall. I am not, though. I like the town and the directors of the club are the nicest men I have ever met, and Mr. [Tacoma owner Dave] Evans wanted me to play with Tacoma this year, but I refuse to have anything to do with Fisher.”27

The downward slide for St. Vrain began in 1905. His pitching in preseason exhibition games was so poor that the Seattle Daily Times wondered publicly why he remained on the Portland roster.28 When no improvement was visible in two early-season Portland appearances (0-1, with a 5.79 ERA), St. Vrain was released. Several weeks later, he signed with the St. Joseph (Missouri) Saints of the Class A Western League, but fared little better there. In eight starts, he went 2-6 and drew his release. At this point, the Seattle Daily Times informed readers that “Jimmy is about all in as a pitcher … and will probably soon resume his old trade as a boilermaker (sic).”29 But St. Vrain had other ideas, hooking on with the Topeka White Sox of the Class C Western Association, for whom he lost all four of his starts.

While the little hurler labored his way through the 1905 campaign, the anecdotes that preserve 12-game major leaguer Jimmy St. Vrain in memory began to appear in print. First was the yarn about how, as a newly arrived Chicago Cub, St. Vrain was induced to make a wearying trek on foot from distant lodgings to the ballpark each morning rather than take a streetcar. It seems that teammate Frank Chance had informed the gullible newcomer that Cubs manager Selee disapproved of his players using streetcars to get to work, and would impose a $50 fine on any of his charges whom he discovered riding to the ballpark on one. The prank was revealed only after Selee asked St. Vrain why he seemed to be so tired when he took the field for morning practice.30 Years later, former manager Mike Fisher repaid St. Vrain for his earlier unkind commentary by recalling an incident from a 1904 Tacoma Tigers game in which St. Vrain supposedly killed a Tigers rally with a baserunning boner. According to Fisher, St. Vrain, stationed as a runner on second, inexplicably reached out and snared a Tacoma line drive headed for the outfield, turning an RBI base hit into the third out. When confronted back in the dugout, St. Vrain told Fisher that “he didn’t know why he did it.”31

But the tale that posthumously immortalized Jimmy St. Vrain stems from a reputed incident during a May 30, 1902, game against Pittsburgh. Although a lefty thrower, St. Vrain was a right-handed batter, and a notoriously poor one, rarely capable of even making contact. Seizing upon an offhand suggestion by manager Selee, St. Vrain stepped into the left-handed batter’s box late in the game and somehow managed to slap a roller to Pittsburgh shortstop Honus Wagner. Disoriented by hitting from an unfamiliar spot, St. Vrain then dashed for third rather than first, much to the amusement of Wagner and the other Pirates. When later asked for an explanation, all Jimmy could say was, “Well, I always was used to run[ning] the way my bat pointed.”32 More than 60 years after the fact, Davy Jones’s embellished version of the incident was a highlight in Lawrence Ritter’s celebrated chronicle of Deadball Era baseball, The Glory of Their Times, and it would be churlish to dwell upon the improbability of the event here. Suffice it to say that contemporaneous press accounts of the game include no mention of it.33

Following his dismal performance in 1905, no record is found of St. Vrain playing during the ensuing season. But early in 1907, Sporting Life reported that Jimmy was pitching for Ziegenheims, a local entry in the St. Louis Trolley League, a crack semipro circuit.34 Thereafter, he reportedly pitched for an independent team in Mexico, Missouri.35 In April 1908, “pitcher St. Vrain, the promising youngster … reported for service” with the Bloomington (Illinois) Bloomers of the Class B Three-I League.36 But no trace of St. Vrain appears in 1908 year-end league statistics. The end of the line for the soon-to-be 38-year-old Peter Pan was reached in Class D ball, where St. Vrain pitched briefly for the Jacksonville (Illinois) Braves of the Central Association.37

During his minor-league career and for a decade thereafter, Jimmy and his wife lived at various addresses in Tacoma, where Jimmy worked offseason as an electrician. Once his playing days were over, being an electrician became his full-time occupation. Registering for the World War I military draft, St. Vrain listed his date of birth as June 6, 1875, continuing the deception that “James St. Varain (sic), League Ball Player,” had perpetrated upon 1900 US Census takers. When the 1930 Census was taken, St. Vrain pushed his birth date up some more, to June 1879.

By 1919 Jimmy and Fanny had relocated to Butte, the place where they had first met 20 years earlier. Upon retiring in the mid-1930s, Jimmy lived quietly, puttering around the house and tending to “one of the most beautiful flower gardens in Butte.”38 Afflicted with arteriosclerosis and hypertension, James Marcellin “Jimmy” St. Vrain suffered a stroke and died at his home on June 12, 1937.39 Based upon information supplied by Fanny, the death certificate listed June 6, 1883, as the St. Vrain date of birth, making the 66-year-old deceased some 12 years younger than his actual age. After services at a local mortuary, Jimmy was buried in Mountain View Cemetery in Butte. Besides his wife, survivors included older brother Paul, and his sister Celess St. Vrain Pierceall.

Notes

1 In its February 2014 newsletter, the Biographical Committee amended the Jimmy St. Vrain date of birth to June 6, 1871. Baseball-Reference immediately followed suit, deleting commentary on his putative youth from the Bullpen Section of its entry on St. Vrain, as well. Other baseball authorities, however, still provide the now-discredited June 6, 1883, date of birth for our subject.

2 See e.g., the James Marcellin St. Vrain posting at http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/20430826/person/1129 357112. The St. Vrain family is well known to historians of the early American West, and various Colorado landmarks (Fort St. Vrain, St. Vrain River, St. Vrain Reservoir, etc.) are named for Jimmy’s fur trader/pioneer uncle, Ceran St. Vrain. Family descendants are active in preserving the St. Vrain legacy, and have posted a goodly number of information-rich biographies, family histories, essays, and family trees on the Internet. For an informative overview of the life of Jimmy’s father and an accounting of his numerous offspring, see the Marcellin St. Vrain bio posted by the Closet Skeleton Genealogical Society.

3 Cincinnati Post, January 23, 1905.

4 Cincinnati Post, January 25, 1905.

5 See Marcellin St. Vrain at http://stvrainsfort.homestead.com/marcellin.html.

6 The children of Marcellin St. Vrain’s marriage to Elizabeth Jane Murphy were Isadora Celeste (1851-1926); Teresa Emma (1854-1873); Eugene William (1856-1929); Maria Felicite (1858-1928); Sarah Helen (1860-1862); Celess (1863-1941); Leona Ann (1865-1889); Paul Augustin (1868-1954); James Marcellin (1871-1937), and Elizabeth Zelena (1871-1899). Marcellin’s sons by his earlier liaison with Indian wife Royal Red – Felix (1842-1863) and Charles (1844-1935) – were members of the St. Vrain household in Missouri during most of the 1850s, while their sister Mary Louise (1848-1916) remained west with her mother. The names and fates of the offspring of Tall Pawnee Woman, Marcellin’s other possible Indian consort, are unknown.

7 Montana Standard, Anaconda, June 14, 1937.

8 Seattle Daily Times, September 30, 1902.

9 A report in the Denver Post, April 29, 1900, that St. Vrain had signed with Pueblo in the Western League appears unfounded. In any event, no record of St. Vrain playing for Pueblo was discovered by the writer.

10 Anaconda (Montana) Standard, August 18, 1900.

11 As recalled by Tacoma manager John McCloskey in the Seattle Daily Times, February 6, 1905.

12 According to the Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, February 6, 1902. Portland’s Clyde Engel (28-11) was presumably the circuit’s premier hurler.

13 As per Sporting Life, February 16, 1902. See also, Rockford (Illinois) Republic, February 8, 1902. Note: During the 1902 season, the National League’s Chicago club was also called the Colts and/or the Orphans by some media. The enduring team nickname Cubs is used herein for purposes of clarity.

14 As reported in Sporting Life, March 1, 1902, and the Seattle Daily Times, March 3, 1902.

15 Sporting Life, March 29, 1902.

16 Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1902.

17 Chicago Tribune, April 5, 1902.

18 Chicago Tribune, May 11, 1902.

19 Sportswriter William A. Phelon: “St. Vrain is pitching good ball for Chicago, but is pursued by a persistent hoodoo.” Sporting Life, May 11, 1902.

20 Anaconda Standard, June 20, 1902.

21 Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1902.

22 Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1902. See also, Sporting Life, June 28, 1902, which observed: “St. Vrain, who is a nice little fellow, realized his own failings, and was willing to take another year in the minor league school, especially with the fat contract for next season in his clothes.”

23 Developments in the Southern Association squabble were featured weekly in the June-October 1902 issues of Sporting Life. For a more complete account of the controversy, see “The Southern Association Squabble of 1902,” by Bill Lamb, The Inside Game, Vol. XIV, No. 2, April 2014. In the end, the tough-minded Charley Frank (with the backing of an equally tough-minded Memphis millionaire named Carnes) faced down baseball’s minor-league establishment, with Memphis being restored to a new Southern Association reconstituted to Frank’s liking. He also received indemnification for his 1902 losses, plus a damage award. Frank later placed his total recompense at $20,000, according to the Charleston News and Courier, August 13, 1908.

24 As per the Dallas Morning News, January 25, 1903, and Sporting Life, January 31, 1903.

25 As reported in the Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, May 21, 1903, and Sporting Life, June 6, 1903.

26 As per the New Orleans Times-Picayune and New Orleans Item, July 7, 1903.

27 Seattle Daily Times, March 7, 1905.

28 Seattle Daily Times, March 7, 1905, and republished verbatim in the Seattle Daily Times, April 10, 1905.

29 Seattle Daily Times, July 1, 1905.

30 See e.g., Dallas Morning News, May 5, 1905, and Seattle Daily Times, June 13, 1905.

31 San Diego Union, March 30, 1930.

32 The quote is attributed to St. Vrain in the Seattle Daily Times, June 10, 1905.

33 See e.g., the Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1902, which does mention, however, that “St. Vrain is the poorest hitter in the league according to the form shown here.” For some skeptical commentary on the alleged event, see http://keitholbermann.mlblogs.com/tag/jimmy-st-vrain/

34 Sporting Life, April 12, 1907. Two months later, it was reported that St. Vrain had to skip a Trolley League pitching assignment due to a death in the family. See Sporting Life, June 22, 1907.

35 As per the Daily (Springfield) Illinois State Register, April 24, 1908.

36 Ibid. See also Sporting Life, May 9, 1908.

37 St. Vrain’s signing with Jacksonville was reported in Sporting Life, March 29, 1909.

38 As per the Montana Standard, June 14, 1937.

39 As per the death certificate contained in the Jimmy St. Vrain file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

James Marcellin St. Vrain

Born

June 6, 1871 at Ralls County, MO (USA)

Died

June 12, 1937 at Butte, MT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.