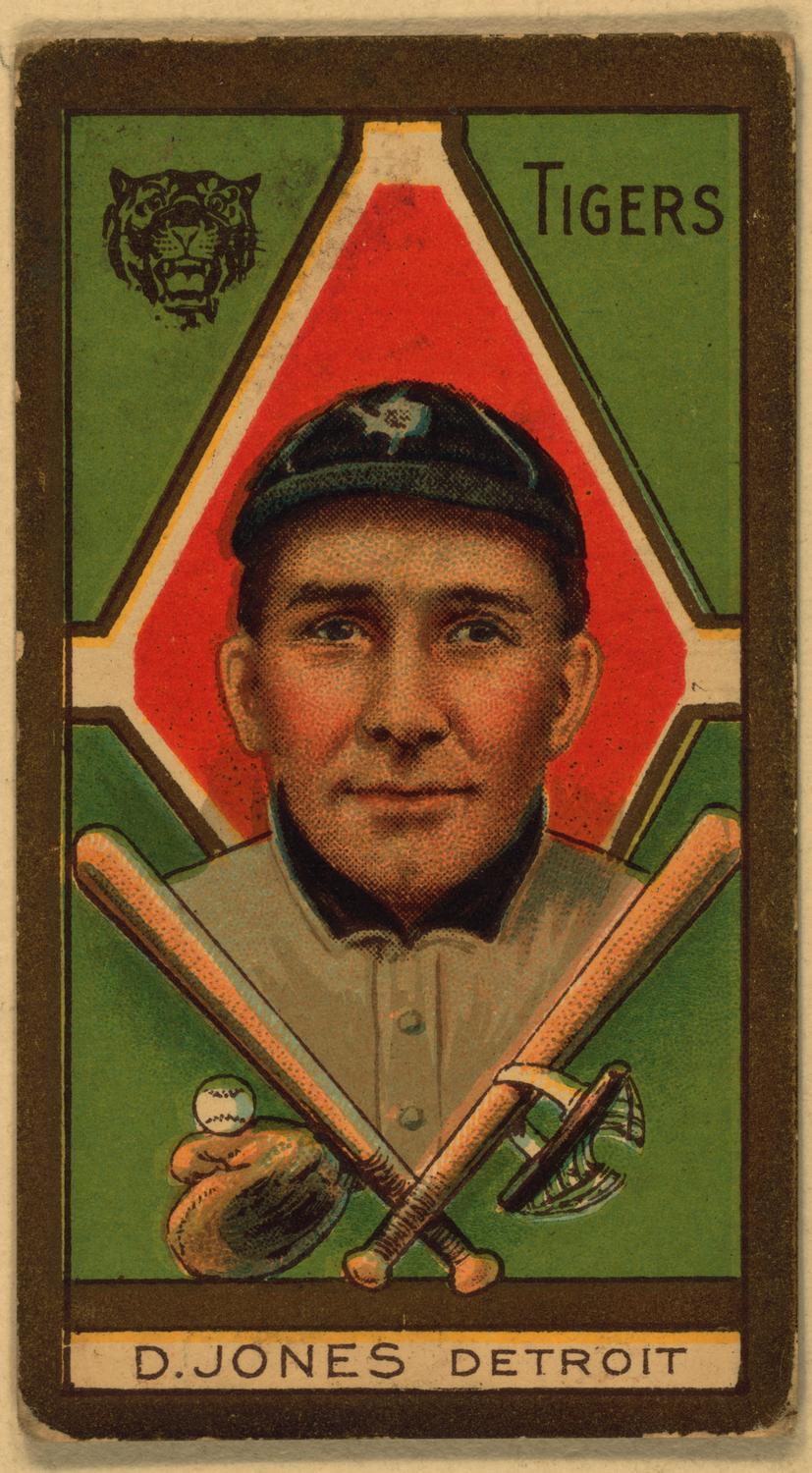

Davy Jones

In his interview with Lawrence Ritter for Ritter’s classic book The Glory of Their Times, Davy Jones described the kaleidoscope of players who enlivened the Deadball Era. “Baseball attracted all sorts of people in those days,” he explained. “We had stupid guys, smart guys, tough guys, mild guys, crazy guys, college men, slickers from the city, and hicks from the country.” At times, Jones himself could seem a bit like all of the above. A rare collegian who possessed a law degree and later went on to a prosperous career in pharmacology, the intelligent Jones could also be quick-tempered and impulsive. Jones had run-ins with umpires, managers, players and fans, and once even bounced a knife-wielding robber from his drugstore. During his first years in the pros he jumped so many contracts that the press nicknamed him “The Kangaroo.” “He signed so many contracts last winter that a half dozen lawyers could not have made a worse tangle,” the Chicago Tribune quipped in 1902. When he finally settled down with the Detroit Tigers, the fleet-footed and pesky Jones became one of the game’s best, though oft-injured, leadoff hitters. His most successful season in Detroit came in 1907, when he helped spark the Tigers to the first of three consecutive American League pennants.

In his interview with Lawrence Ritter for Ritter’s classic book The Glory of Their Times, Davy Jones described the kaleidoscope of players who enlivened the Deadball Era. “Baseball attracted all sorts of people in those days,” he explained. “We had stupid guys, smart guys, tough guys, mild guys, crazy guys, college men, slickers from the city, and hicks from the country.” At times, Jones himself could seem a bit like all of the above. A rare collegian who possessed a law degree and later went on to a prosperous career in pharmacology, the intelligent Jones could also be quick-tempered and impulsive. Jones had run-ins with umpires, managers, players and fans, and once even bounced a knife-wielding robber from his drugstore. During his first years in the pros he jumped so many contracts that the press nicknamed him “The Kangaroo.” “He signed so many contracts last winter that a half dozen lawyers could not have made a worse tangle,” the Chicago Tribune quipped in 1902. When he finally settled down with the Detroit Tigers, the fleet-footed and pesky Jones became one of the game’s best, though oft-injured, leadoff hitters. His most successful season in Detroit came in 1907, when he helped spark the Tigers to the first of three consecutive American League pennants.

David Jefferson Jones was born on June 30, 1880, in Cambria, Wisconsin (about 40 miles north of Madison), to Welsh immigrants. His father was a city street commissioner. Davy attended elementary school in Cambria and high school in nearby Portage, where he lettered in baseball, football, and track. A very fast runner, Davy used his speed to earn money in foot races. He often raced fellow Wisconsinite Archie Hahn, later the world record holder in the 100 yard dash and a 1904 and 1906 Olympic gold medal winner, and liked to boast how he beat him several times.

After graduating from high school, Jones worked on the railroads for a short time before enrolling at Dixon College in northern Illinois in the fall of 1899. His skill in sports had earned him a scholarship to Dixon, where he studied law, eventually completing a two-year degree program. While at Dixon, Davy played football and baseball and was a sprinter on the track team. In 1901, during his final year there, the baseball team traveled to Rockford for a couple of exhibition games with the local minor league club. After helping to drub the professionals on successive days, Davy was persuaded, after much cajoling by manager Hugh Nicol, to sign a contract and report to Rockford upon completion of the college season..

Appearing in 77 games for Rockford in 1901, Davy won the Three-I League batting title with an average of .384 and attracted the attention of big league scouts. His eventual debut in the major leagues was not without a bit of controversy, however. Rockford sold him to the Chicago National League club, but Jones jumped his first contract, electing to stay closer to home and finish the 1901 season with the American League’s Milwaukee Brewers, where he batted .173 in 52 at bats.

When the Brewers moved to St. Louis after the 1901 season, Jones took advantage of a clause in his AL contract which prevented transferring a player to a new city without his consent. The young lawyer signed with Chicago, which still owned his rights within organized baseball. Later that winter he jumped back to St. Louis, but played in only 15 games in 1902 before jumping back to Chicago after Orphans owner James Hart offered Davy a fifty percent raise and $500 signing bonus. All told, Jones had jumped four different contracts in a nine-month span. Jones left his Browns teammates without a word on the morning of May 14 and was patrolling centerfield for the Cubs that afternoon. Though a major leaguer for barely a month all told, Davy was quickly gaining a reputation for jumping contracts whenever a better offer came along. The Chicago Tribune referred to him as a “rubber-leg,” and Chicago fans even quit teasing fellow outfielder Jimmy Slagle, another noted jumper, out of deference to Jones. As Jones himself said later, “a contract didn’t mean anything in those days.”

When healthy, Davy was Chicago’s starting center fielder, but injuries and illness cut into his playing time. In August of 1902, he contracted typhoid and did not return to the lineup, missing the final 43 games. In 1903, he missed only nine games and hit .282. During a Fourth of July doubleheader in 1904, however, he collided with Pittsburgh catcher Harry Smith and suffered a broken leg. Upon his return to the lineup in mid-August, his play was greatly hampered by the injury. Although he played in most of the club’s remaining games, with limited speed and mobility Davy’s average dipped and his outfield range (he was now in right field) vanished. When the leg failed to show improvement the following spring, he was sold to the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers released just prior to Chicago’s departure for spring training in Los Angeles.

Jones played centerfield for the 1905 Millers where, under the tutelage of manager W.H. Watkins, his base running and defense greatly improved as he recovered from the leg injury and learned to harness his tremendous speed. His .346 average placed second in the league and his overall play attracted the attention of Detroit’s Frank Navin and Bill Armour, who had come to scout catcher Boss Schmidt. The Tigers bought three Minneapolis players–Jones, Schmidt, and pitcher Ed Siever–after watching the Millers play a doubleheader in Toledo.

Reporting to the Tigers in 1906, Davy moved into the starting center field role. Injured in late August, Jones appeared in 84 games for Detroit, batting .260 but drawing 41 walks for a .347 OBP, second best on the team to Ty Cobb. The Tigers finished a disappointing sixth in the AL, but things were beginning to look up for Detroit. Davy enjoyed his finest season in 1907, as the Tigers captured their first of three consecutive American League pennants. Switched to left field and batting leadoff, Jones posted a .357 OBP and scored 101 runs, second best in the American League. Davy also swiped a career-best 30 bases, tied for eighth in the league. Playing against the team that discarded him in that year’s World Series, Jones performed well, batting .353 with a .476 OBP, but the Tigers were no match for the powerful Chicago Cubs, losing in five games.

Despite the solid year, Jones sat the bench for much of the 1908 season as Matty McIntyre, the Tiger veteran whom he had displaced in 1907, reclaimed left field. The result was Jones’s most unsatisfying season to date. Appearing in only 56 games, many as a pinch hitter or runner, he batted a mere .207. The following season Davy once more was forced to defer to McIntyre, playing in only 69 games, but he was far more valuable to the Tigers in the games he did play than in 1908, scoring 44 runs. In the World Series against the Pirates, it was McIntyre who was relegated to the bench as Davy started every game. Despite scoring six runs in the seven games and bouncing a homer into the stands to lead off Game Five, Davy batted only .231 and could not reach base with any regularity. The Tigers lost their third straight World Series, the only AL club ever to do so.

During the 1910 season, Jones opened a drugstore in the Detroit area, putting his younger brother Arthur, who was a druggist, in charge. A success from the start, the Davy Jones Drug Company eventually grew into a five-store chain, with its namesake being the main attraction. Wall-to-wall customers lined up after games for sodas and conversation with the Tigers star. Davy soon began to study pharmacy and learn the drug business himself.

Although Detroit failed to capture another pennant, Davy remained a valuable part-time player for the Tigers from 1910 through 1912, though his combative temperament caused numerous headaches for Tigers management. In June 1910, Jones got into a fistfight with his former St. Louis manager, Jimmy McAleer, then managing the Washington club, and was handed a fine and weeklong suspension. In May 1912, Jones served as a catalyst for Cobb’s famous brawl with a fan in New York’s Hilltop Park. After Cobb endured several innings of vitriolic abuse from a handicapped spectator, Jones reportedly said to him, “if you don’t go up to knock that guy’s block off, I’m going to do it!” When Cobb charged into the stands to confront the heckler, Jones helped to prevent onlookers from interfering.

In mid-June, before the Cobb commotion had cooled, Davy got into another tangle, this time with umpire Billy Evans in Philadelphia. Disagreeing with Evans’s pitch calling, Jones challenged him to a fight after the game. When Evans came to the Tigers’ dressing room, he was reportedly intercepted and roughed up by several of Davy’s teammates. Both were fined and Jones received another suspension.

Wearying of the controversy, the Tigers decided Jones’s best playing days were behind him. Following the 1912 season, Jones was sold on waivers to the Chicago White Sox. Davy appeared in only 12 games for Chicago in 1913 before he was sold to Toledo. Refusing to report and take a pay cut, eventually agreed to terms and became one of the American Association’s top hitters. Prior to the 1914 season, however, the 33-year-old Kangaroo jumped to the Pittsburgh Rebels of the newly-formed Federal League. Jones played passably for the Rebels in 1914, scoring 58 runs in 97 games before injuring his ankle. Davy appeared in only 14 games in 1915 before being released.

His baseball career over, Davy earned a Ph.G. in Pharmacy from the University of Southern California and moved back to Michigan, where he became licensed as a pharmacist and worked in his drug stores for the next 40 years.

Davy’s first marriage, to Mae W. Maynard, lasted 52 years and produced two children. After Mae’s death in 1955, Jones remarried–to his high school sweetheart of 60 years earlier–and moved to Milwaukee in the late 1950s and later to Mankato, Minnesota. Jones died of a heart ailment at his home in Mankato, on March 30, 1972, at the age of 91. He was survived by his wife Margaret and is buried in Roseland Park Cemetery in Berkeley, Michigan, a Detroit suburb.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Note: Information on Jones’s 1918 appearance was discovered and researched by the author, Dan Holmes at the HoF, and Marc Okkonen. In early August, 2004, the Elias Sports Bureau agreed that the new information justified changing Jones’s official playing record to reflect the inclusion of that final game.

Sources

badgerstategames.org (Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame website)

Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1906

Chicago Tribune, 1901-1918

Washington Post, 1901-1918

The Sporting News, 1901-1972

Sporting Life, 1906-1912

New York Times, 1901-1972

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1912

Mankato Free Press, 1972

Lawrence Ritter. The Glory of Their Times. McMillan, 1966. Also, the audio recordings.

Davy Jones player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, including Jones’s personal correspondence with Lee Allen and the transcript of his original interview with Lawrence Ritter for The Glory of Their Times

Full Name

David Jefferson Jones

Born

June 30, 1880 at Cambria, WI (USA)

Died

March 30, 1972 at Mankato, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.