Honus Wagner

“There ain’t much to being a ballplayer, if you’re a ballplayer,” said the greatest player of his time, or most any other time — Honus Wagner. He may be the greatest player in National League history.

“There ain’t much to being a ballplayer, if you’re a ballplayer,” said the greatest player of his time, or most any other time — Honus Wagner. He may be the greatest player in National League history.

One of five sons and four daughters of the former Katrina Wolf and Peter Wagner, Honus (a diminutive of Johann or Johannes, the German equivalents of John) was born Johannes Peter Wagner in the coal country of western Pennsylvania on February 24, 1874. The Wagners lived in the tiny borough of Chartiers, about six miles southwest of downtown Pittsburgh.

Albert, an older brother considered the best ballplayer in the family, began playing the game professionally, and in 1895 when his Steubenville, Ohio, (Inter-State League) team needed help, he suggested Honus. Honus’s first year was an odyssey covering five teams, three leagues, and 80 games. He hit wherever he played (between .365 and .386) and showed his versatility by playing every position except catcher.

Edward Barrow, wearing several hats with the Wheeling, West Virginia, team (Iron and Oil League), liked what he saw and in 1896 took Honus with him to his next team, in Paterson, New Jersey (Atlantic League). Honus rewarded Barrow’s faith by playing wherever he was needed –first, third, the outfield, or second – and hitting .313 with power and speed. He followed up by hitting .375 in 74 games for Paterson in 1897.

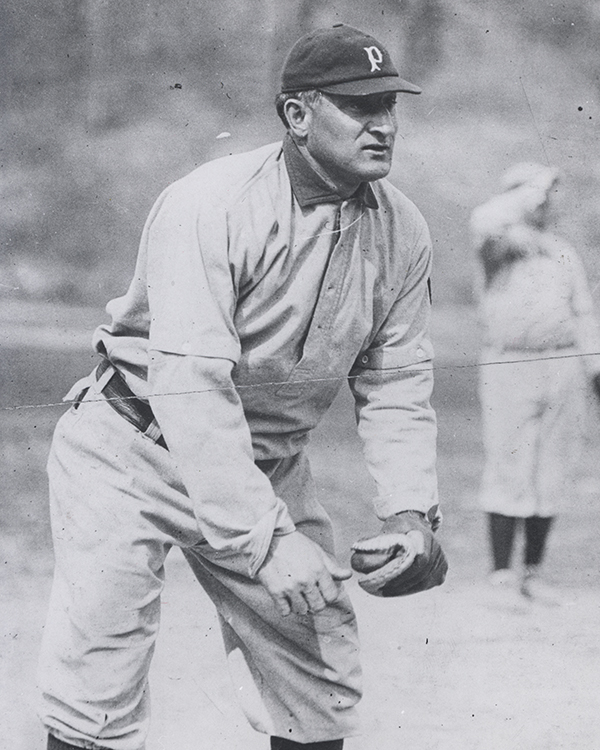

Recognizing that Wagner should be playing at the highest level, Barrow contacted the Louisville Colonels, who had finished last in the National League in 1896 with a record of 38-93. They were doing better in 1897 when Barrow persuaded club president Barney Dreyfuss, club secretary Harry Pulliam, and outfielder-manager Fred Clarke to go to Paterson to see Wagner play. Dreyfuss and Clarke weren’t impressed with the awkward-looking man, not surprising, as Wagner was oddly built – 5-feet-11, 200 pounds, with a barrel chest, massive shoulders, heavily muscled arms, huge hands, and incredibly bowed legs that deprived him of any grace and several inches of height. Pulliam, though, persuaded Dreyfuss and Clarke to take a chance on him. Wagner debuted with Louisville on July 19, and hit .338 in 61 games.

Pulliam was right. The awkward-looking Honus would become the best pure athlete in the game. Seeing Wagner at bat, standing straight up waiting for the pitch, was to witness raw power. He held his heavy bat (well over 40 ounces) with his hands several inches apart, a grip that allowed him to slap an outside pitch to right at the last moment or slide his hands together and pull an inside pitch down the left-field line. Now obsolete, the split-handed grip was relatively popular in the early part of the twentieth century. Wagner and Ty Cobb used it, winning 20 batting titles and accumulating about 7,600 hits between them.

Honus was deceptive on the bases, too. He didn’t look fast, but he stole over 700 bases and legged out almost 900 doubles and triples. His speed got him the nickname “The Flying Dutchman.” In baseball, as in the worlds of myth and legend, titles and nicknames are earned. (The direct albeit coincidental allusion to the myth and Richard Wagner’s opera of the same name didn’t hurt, either.) Wagner’s form as seen in early film was distinctive as he tore around the bases with his arms whirling like a berserk freestyle swimmer. Honus thought the arm motion gave him speed, and he got results.

Wagner was a sight in the field as well. His huge hands made it difficult to tell whether he was wearing a glove. The glove that seemed too small for his hand was made even smaller by cutting a hole in the palm and pulling out much of the stuffing. Doing so, he thought, gave him better feel and hand mobility, reasonable given the pancake-shaped glove he used. Quick of foot and reflex, he covered the left side of the infield, knocking down balls (making errors on balls that other shortstops wouldn’t have reached) as necessary and throwing out runners with his powerful arm. He would irritate Clarke by taking his time making the throw on close plays at first. Wagner told Clarke he’d change when he quit throwing runners out. His one weakness in the field stemmed from his oversized feet, which sometimes got in the way. At bat, on the bases, and in the field, Wagner wasn’t pretty, just effective.

Wagner played in 151 games in 1898, handling first, second, and third, and hitting .299. He wouldn’t see the south side of .300 again until 1914. Louisville improved to 75-77 in 1899, helped by Honus’s hitting. That winter things would change drastically for all concerned.

National League officials reduced league membership from 12 teams to eight. The Louisville club was dissolved. Dreyfuss bought stock in the Pittsburgh Pirates and through clever maneuvering became president of the club. Replacing unproductive Pirates with top players from Louisville, including Wagner, Dreyfuss pushed the Pirates to second behind the Brooklyn Superbas in 1900. Wagner thanked Dreyfuss for bringing him home, hitting and slugging career-bests .381 and .573.

The decade spanning 1900 to 1909 belonged to Wagner. He led in every significant category except triples (second behind Sam Crawford of the Cincinnati Reds and Detroit Tigers) and home runs, (tied for fifth). A summary of Wagner’s year-by-year hitting titles shows the following: batting average (7 times); on-base percentage (4); slugging (6); runs scored (2); hits (1); total bases (6); doubles (7); triples (3); RBIs (4); and stolen bases (5). Furthermore, he led the league in various categories up to 1912 and stayed among the leaders a few years after that.

The rise of the American League in 1901 triggered bidding wars and player raids that decimated most National League teams. Wagner showed his loyalty to Dreyfuss, the Pirates, and Pittsburgh by refusing an offer of $20,000 up front from Chicago White Stockings pitcher-manager Clark Griffith. The tale, perhaps apocryphal, doesn’t hurt Wagner’s legacy.

Pittsburgh survived the war between the leagues relatively unscathed, capturing the pennant from 1901 to 1903 and the World Series in 1909, and remaining strong throughout the decade. The team’s won-lost record of 938-538 and winning percentage of .636 are the best of the period.

Led by Wagner, the 1901 Pirates began a three-year stranglehold over the National League. Their 90-49 record was 7½ games better than the Philadelphia Phillies, with Wagner’s 126 RBIs the major-league best for the decade. The 1902 unit went 103-36, storming to a major-league record 27½-game margin over runner-up Brooklyn. Honus contributed by leading the league in slugging, doubles, steals, runs, and RBIs. The Pirates couldn’t decide where to play him, though. He had played every position except catcher at least adequately, often brilliantly. In two stints on the mound he gave up no earned runs (but several unearned ones), giving him the lowest ERA of anyone in the Hall of Fame – 0.00. His roaming around the diamond would change in 1903, as he finally found his permanent home at shortstop.

Wagner had primarily played shortstop in 1901, especially after the Pirates’ longtime shortstop Bones Ely jumped to the American League. Wid Conroy took over the position for the 1902 season, moving Wagner to right field, but he turned out to be a spy for the American League and was released. Clarke then put Tommy Leach at short and Wagner at third, instructing Leach to persuade Honus to swap positions. The con game worked, as Honus grudgingly took the position for good.

Position notwithstanding, Wagner led the league at .355. The Pirates were weakened by the defection of their top pitcher, Jack Chesbro, to the New York Highlanders (now the Yankees) but still took the pennant, going 91-49. During the season Dreyfuss challenged the American League to a championship playoff at the end of the season. Henry Killilea, president of the league champion Boston Americans (now the Red Sox), accepted the challenge. The World Series was born.

Though plagued with injuries – Wagner’s right leg, pitcher Sam Leever’s sore arm, and pitcher Ed Doheny’s emotional collapse – the Pirates went into the best-of-nine Series as the favorites. Deacon Phillippe, the only healthy Pirate pitcher, threw complete games to take the first, third, and fourth games. Wagner went 5-for-14 and drove in three runs. Phillippe’s arm gave out, and Boston won four straight behind pitchers Cy Young and Bill Dinneen and third baseman-manager Jimmy Collins to take the Series. The last four games were a nightmare for Wagner: 1-for-14, no RBIs, and the humiliation of making the final out of the Series on a called third strike. Worse, the acknowledged greatest player in the National League had led in only one category – errors, with six. Several Boston writers, noting Wagner’s miserable performance, implied that he might be “yellow,” a slap that would haunt him for years.

From 1904 to 1907, the Pirates moved back and forth between second and fourth place, occasionally challenging the New York Giants and the Chicago Cubs on their runs to glory. Wagner was still Wagner, always among the league leaders. He won the first of four consecutive batting titles in 1906 and led the league in doubles and runs.

Honus’s offseasons had been matters of routine. Tending to gain weight, he stayed in shape by fishing, hunting, and taking up the new sport of basketball, playing on several local teams. The horseless buggy allowed him to indulge in “automobiling,” as it was called. More enthusiastic than able, Honus had several mishaps while driving. He opened a garage to repair cars and sell the Regal; no salesman, he loved tinkering with engines. He raised chickens. He hated spring training and held out on principle or did anything he could to avoid or at least delay it. There were plenty of friends to lift a glass with. And with simple tastes and frugal (but not miserly) living, not to mention Dreyfuss’s wise investment help and some good real-estate properties, he was on solid financial ground. He retired.

How genuine Wagner’s retirement was is debatable. He said he was tired, had suffered his share of injuries, and wanted to take at least a year off. Dreyfuss refused to panic at losing his star, in public anyway. It’s possible, even likely, that Wagner was using his “retirement” to get a hefty raise. In any case, Dreyfuss doubled Honus’ salary to $10,000 (the figure he maintained until his last season), making him the highest-paid player in the game for several years.

Wagner put together his greatest season in 1908. Both leagues hit just .239, but Honus didn’t notice. His .354 batting average led the league comfortably. Settling for second in homers and runs scored, he led in everything else. It added up to an offensive winning percentage of .878 in Lee Sinins’ Sabermetric Baseball Encyclopedia – the greatest single season in National League history until Barry Bonds’ astounding 2001 through 2004 seasons.

And it wasn’t enough. In the closest National League pennant race ever, the Pirates could have forced a three-way tie with the Cubs and Giants by winning their finale against the Cubs. Instead, they lost, 5-2, Wagner’s two errors not helping. The ghosts of 1903 were alive and well.

A winter of frustration, brooding, and anger brought the Pirates back with a vengeance in 1909. They went 110-42 for the greatest season in club history, six games better than the Cubs. The Cubs got one measure of satisfaction, with Ed Reulbach beating Vic Willis, 3-2, on June 30 to spoil the opening of the new Pirates home, Forbes Field. Otherwise, it was the Pirates’ year, and Wagner carried them with league-leading figures in hitting, slugging, on-base percentage, doubles, RBIs, total bases, and extra-base hits. The stage was set for the best-of-seven World Series with the Detroit Tigers, coming off their third straight American League title and their nominee for baseball’s top player, Ty Cobb.

The Series didn’t disappoint, as the Pirates won in seven games behind the pitching of Babe Adams and the hitting of ageless wonders Wagner, Clarke, and Leach. Wagner outplayed Cobb, hitting .333 to .231 for Cobb, stealing six bases to Cobb’s two, and getting six RBIs to five. Honus’s six steals stood as the Series record until Lou Brock stole seven in both 1967 and 1968. The Series victory was particularly sweet for Wagner, who had vindicated himself.

The Series provided one of the most noted (probably) non-events in the October madness. The Cobb-Wagner confrontation has been hashed over countless times. This much is certain: In the fifth inning of the first game Cobb reached first. The rest is folklore that has become a morality play.

Cobb called Wagner “Krauthead,” warning him that he intended to steal second on the next pitch. Wagner told “Rebel” he’d be waiting. Then Wagner laid a tag on Cobb’s mouth that – depending on the version – knocked out or loosened teeth, or opened a multi-stitch cut on Cobb’s lip. There are several holes in the story. First, “kraut” and “krauthead” as slurs for people of German descent didn’t arise until the World Wars. Second, catcher George Gibson’s throw was low and late, forcing Wagner to try a swipe tag, so he couldn’t tag Cobb hard. Third is Cobb’s categorical denial of the incident, noting that angering Wagner would have been foolhardy. (However, Cobb also suggested to Wagner that they go into vaudeville to re-enact the play, reasoning that they might as well make a few dollars from it.) A final objection to the tale is that a month after the Series Wagner accepted Cobb’s invitation to Georgia for some hunting. Honus didn’t exactly say it happened, didn’t exactly say it didn’t – winking and never discouraging those who “saw the whole thing.”

On paper Wagner’s 1910 season looks decent. Although his .320 average was his lowest since 1898, he tied teammate Bobby Byrne for the league lead in hits with 178. The season was in fact a disaster. The Pirates fell to third behind the Cubs and Giants and were never in the pennant race, finishing a distant 17½ games behind league-leading Chicago. Wagner struggled, hitting well below .300 while fielding lackadaisically, and only a late-season surge got him to acceptable territory. The Pirates attributed his subpar performance to an injury, then a lingering cold, or maybe just a slump, but the real cause was an open secret – his out-of-control drinking. Honus had more than his share of run-ins with umpires, receiving several ejections and suspensions, and some ugly confrontations with teammates. The situation was serious enough for Clarke to have a long talk with Wagner after the season.

The only good thing to come out of 1910 was the now-famous T-206 card, one of which commanded over $1 million at auction in 2000. Pirates secretary John Gruber, making $10 on the deal, sold the American Tobacco Company a picture of Wagner to reproduce in card form to be inserted in Piedmont cigarettes. Wagner, who smoked cigars and chewed but didn’t like cigarettes, stopped the deal, sending Gruber a check for $10. Wagner didn’t want kids buying cigarettes and didn’t think they should have to pay for his picture. The few cards that got out before the print run could be stopped were snapped up and held, making the Wagner T-206 card the most prized sports card on record.

Honus had his last big seasons in 1911 and 1912, winning his final batting title in 1911 and finishing second in the league in RBIs the next year. He hit exactly .300 in 1913, the last time he would reach that level.

Wagner and the Pirates declined together. The team fell to seventh in 1914 as Wagner hit .252. On June 9 he got his 3,000th hit, doubling against Philadelphia’s Erskine Mayer to become the first player to achieve that milestone in the twentieth century. The team improved to fifth in 1915 with Honus having something of a last hurrah. Playing all 156 games, he had enough left in his battery to leg out 32 doubles and 17 triples and drive in 78 runs. The season had one highlight, as he hit a grand slam off Brooklyn’s Jeff Pfeffer on July 29. Forty-one years old at the time, he was thought to be the oldest player to hit a grand slam.1

Clarke retired after the 1915 season. Dreyfuss brought in Jimmy Callahan, but the Pirates fell to sixth. Wagner’s modest .287 was good enough for eighth in the league. Honus ended 1916 on a bright note, though, on December 31 marrying Bessie Baine Smith, whom he’d been seeing for several years.

Wagner was dubious about playing another year. Bessie’s cooking was having its effect on his waistline, and he wasn’t working out or hunting much. He started the season fairly well, but he and the Pirates were finished, the team dropping to the cellar while he hit .265 in just 74 games. Callahan was fired, and Honus, who had served as acting manager when Clarke was unavailable, agreed to take over, but after winning his first game and losing the next four, he told Dreyfuss the job wasn’t for him. He played his last game on September 17, three innings at second base.

Wagner’s final résumé included major-league records (at the time) for games, at-bats, extra-base hits, and total bases. In addition, he held National League records for doubles, triples, and batting titles (8, later tied by Tony Gwynn). He’s second behind Cap Anson in hits (3,435 to 3,420), RBIs (2,075 to 1,733), and runs scored (1,999 to 1,739). His 733 stolen bases rank third behind Billy Hamilton’s 914 and Arlie Latham’s 742.2

The Wagners awaited the birth of their first child. Tragically, Elva Katrina was stillborn on January 9, 1918. Honus threw himself into war work, making speeches urging Americans to buy Liberty Bonds and becoming an entertaining speaker. Betty Baine Wagner was born on December 5, 1919, followed by Virginia (Ginny) Mae on May 3, 1922. A doting father, Honus took the girls everywhere, taught them to play ball, and called them “my boys.” Betty married Harry Blair in 1948 and two years later presented Bessie and Honus with Leslie Ann, their only grandchild and descendant. Answering to “Buck Jay” from an adoring Leslie, Honus read to his little sweetheart and slipped her the occasional Hershey bar.

Wagner’s life after he finished playing was a mix of highs and lows. He had political jobs: state fish commissioner and sergeant-at-arms of the Pennsylvania legislature. He bought properties around Carnegie, building on them and making a decent rental income. He coached the Carnegie High School football team and the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) basketball and baseball teams. Most prominent of his ventures was the sporting-goods store bearing his name. The business went through several weak phases, as Wagner lacked business sense and had some less than ideal partners. Honus and Pie Traynor, an honest man as well as a great third baseman, tried to make a go of it, but the Depression finished it off.

Wagner’s life after he finished playing was a mix of highs and lows. He had political jobs: state fish commissioner and sergeant-at-arms of the Pennsylvania legislature. He bought properties around Carnegie, building on them and making a decent rental income. He coached the Carnegie High School football team and the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) basketball and baseball teams. Most prominent of his ventures was the sporting-goods store bearing his name. The business went through several weak phases, as Wagner lacked business sense and had some less than ideal partners. Honus and Pie Traynor, an honest man as well as a great third baseman, tried to make a go of it, but the Depression finished it off.

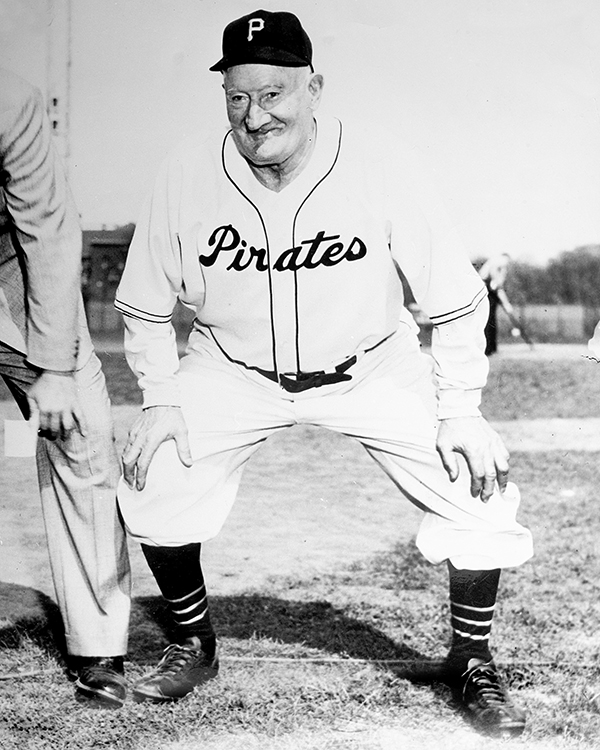

The Wagners were hit fairly hard by the Depression. William Benswanger, taking over the Pirates’ leadership after the death of his father-in-law, Barney Dreyfuss, heard of Wagner’s situation in 1933 and gave him a coaching job. Honus’s first task was to make a big-league shortstop out of the hard-hitting Arky Vaughan, who went on to a Hall of Fame career. He primarily coached and encouraged the rookies, becoming a substitute father to them, and chatted with the fans. He spun yarns, like the time he scooped up a grounder in his steam-shovel hands along with grass, pebbles, and a rabbit that had run onto the field and heaved the whole mess to first, nailing a fast runner – by a “hare.” Once shy, he became a fine after-dinner speaker and barroom raconteur. Age and injuries catching up with him, he retired in 1951.

Beyond Bessie and the “boys,” the grandest moment of Honus’s life was his election in 1936 – with Cobb, Babe Ruth, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson – as one of the five charter members of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He starred at the induction ceremonies on June 12, 1939, reminiscing with the giants of a bygone era.

Honus lived out the remainder of his years at home in Carnegie, making his customary journeys to the Elks Club and the various watering holes that Pittsburgh offered. He made his last public appearance on April 30, 1955, at the unveiling of the Frank Vittor statue of him that would stand in Schenley Park outside Forbes Field. Too weak to leave the car, he waved to the crowd and left before the ceremonies ended. The 10-foot-high bronze statue atop a granite base shows Wagner following through on his swing and watching the flight of the ball. The monument later graced the entrance to Three Rivers Stadium and now greets visitors to PNC Park, the Pirates’ current home.

Beset by injuries, illness, and age, Honus Wagner died in his Carnegie home at 12:56 A.M. on December 6, 1955, less than an hour after Betty’s birthday. He was buried on December 9 in Jefferson Memorial Cemetery in Pleasant Hills, south of Pittsburgh.

Honus Wagner was no angel or saint. Some opponents thought him a fine fellow off the diamond but overly rough on it. Most umpires thought he “kicked” too much. He affected to dislike formal affairs, but he really hated the next morning. Yet he also embodied the American dream as the son of immigrants who rose from humble roots to greatness. Frailties aside, he was one of baseball’s first heroes, a basically gentle, hard-working man, a loyal friend and teammate who treated young players kindly, dealt with adversity, inspired millions, and was devoted to Bessie, the “boys,” and Leslie. Bill James in The Historical Baseball Abstract put it best: “[T]here is no one who has ever played this game that I would be more anxious to have on a baseball team.”

Last revised: September 23, 2022 (zp)

An updated version of this biography is included in “Nuclear Powered Baseball: Articles Inspired by The Simpsons Episode Homer At the Bat” (SABR, 2016), edited by Emily Hawks and Bill Nowlin. It originally appeared “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Jay Brinton for helping me correct my description of Frank Vittor’s statue of Wagner. Special thanks go to David Jones, Tom Simon, Russ Lake, Len Levin, and Bill Nowlin, whose editing, fact-checking, and encouragement have made this a better piece.

Sources

Unless noted otherwise, all statistics are from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Anderson, David W. More Than Merkle: A History of the Most Exciting Baseball Season in Human History (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

DeValeria, Dennis, and Jeanne Burke DeValeria. Honus Wagner: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995).

Fleming, G.H. The Unforgettable Season: The Most Exciting & Calamitous Pennant Race of All Time (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981).

Hageman, William. Honus: The Life and Times of a Baseball Hero (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1996).

Hittner, Arthur D. Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball’s “Flying Dutchman” (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland, 1996).

Hoie, Bob, Carlos Bauer, et al, eds. L. Robert Davids, The Historical Register: The Complete Major & Minor League Record of Baseball’s Greatest Players (San Diego and San Marino: Baseball Press Books, 1998).

Honig, Donald. The Greatest Shortstops of All Time (Dubuque, Iowa: Elysian Fields Press, 1992).

Honus Wagner Files at the Carnegie Library (Main Branch) in Pittsburgh.

Honus Wagner Files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

James, Bill. The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Villard Books, 1986).

Lieb, Frederick G. The Pittsburgh Pirates: An Informal History (New York: Putnam, 1948).

Meany, Tom. Baseball’s Greatest Hitters (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1950).

_____. Baseball’s Greatest Teams (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1949).

Ritter, Lawrence S. The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It (New York: Macmillan, 1966).

Thorn, John, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman, eds. Total Baseball. 7th ed. (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001).

Because of the huge amount of material on Wagner, this list is necessarily selective. For an exhaustive listing, see The Baseball Index (TBI), accessible through the Society for American Baseball Research website at baseballindex.org.

Notes

1 L. Robert Davids noted that Cap Anson was 42 on August 1, 1894, when he hit a grand slam (the only one of his long career) off the St. Louis Browns’ Ernie Mason. For discussion see L. Robert Davids, “Young and Old Home Run Hitters” at http://research.sabr.org/journals/young-and-old-home-run-hitters. In addition, Julio Franco likely put the old-age grand slam record out of reach on June 27, 2005, when as a 46-year-old pinch-hitter he victimized the Florida Marlins and Victor De Los Santos.

2 Anson’s numbers include his five years in the National Association. The figures comply with those available in November 2014. However, since research into statistics is a continually ongoing process, we must take our numbers with a grain of allowance. As Alan Schwarz admonishes us in Chapter 8 of The Numbers Game: Baseball’s Lifelong Fascination With Statistics, “All the Record Books Are Wrong.”

Full Name

John Peter Wagner

Born

February 24, 1874 at Chartiers, PA (USA)

Died

December 6, 1955 at Carnegie, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.