Bid McPhee

John Alexander “Bid” McPhee, baseball’s greatest second baseman of the 19th century, was born on November 1, 1859, in Massena, New York, the fourth among five children of a saddle-maker. When he was seven, his family moved to the Mississippi River town of Keithsburg, Illinois, a small hamlet of 1200 inhabitants. Keithsburg was the birthplace of Parke Wilson, a catcher for the New York Giants from 1893 to 1899. Wilson’s father was running a dry goods store in the town, and McPhee was for some time an all-around helper in the store. Both Wilson and McPhee played with a local team called the Ictorias.

John Alexander “Bid” McPhee, baseball’s greatest second baseman of the 19th century, was born on November 1, 1859, in Massena, New York, the fourth among five children of a saddle-maker. When he was seven, his family moved to the Mississippi River town of Keithsburg, Illinois, a small hamlet of 1200 inhabitants. Keithsburg was the birthplace of Parke Wilson, a catcher for the New York Giants from 1893 to 1899. Wilson’s father was running a dry goods store in the town, and McPhee was for some time an all-around helper in the store. Both Wilson and McPhee played with a local team called the Ictorias.

The team played all the clubs of the surrounding towns, being a leading feature for the country fairs at that time. The Ictorias won first prize in the district league, which consisted of a nickel-plated bat. McPhee was a catcher then and the youngest player on the Ictorias at just 16. In 1877 he and Elmer Rockwell were signed by Davenport of the Northwest League, and they constituted what was then known as a crack battery, with Rockwell in the pitcher’s box and McPhee behind the bat.

At Davenport in 1878, McPhee batted .333 with 65 hits in 39 games. He returned to Davenport the following season, playing second base as well as right field and catcher, but batted only .229 with 19 hits in 20 games.

In 1880, perhaps discouraged by his lack of success in pro ball, McPhee secured a position as a bookkeeper in Davenport. He made more money keeping books than playing ball, and he apparently liked the job.

In the summer of 1881, though, McPhee was induced to go to Akron, Ohio, where he played second base for an independent team of that town. Although no records exist of his play at Akron in either 1880 or 1881, he must have blossomed, because Cincinnati of the American Association signed him for their inaugural season of 1882. McPhee’s teammates at Akron, Sam Wise and Rudolf Kemmler, were also secured by Cincinnati.

However, as the spring of 1882 approached and the time of reporting to Cincinnati drew near, McPhee, who held the position of bookkeeper in a business house in Akron, became possessed with the idea that he had achieved all the fame he desired in baseball and that he would settle down to be a. businessman. It required considerable persuasion to induce McPhee to give up his books, and it was only after dozens of letters had been written and several trips made to Akron by Cincinnati officials that he decided to continue his career on the diamond.

McPhee was lauded in the Cincinnati newspapers as an “honest man and the best second baseman in the world.” However, in his and his team’s first game against Pittsburgh on May 2 in Cincinnati, McPhee made a very poor showing. McPhee later referred to his own play as “rotten” and he provoked hoots and jeers from the Cincinnati fandom, who suffered through a 10-9 loss. In an 1890 interview, McPhee recalled. “What broke me up worse than anything else was a little episode that occurred after the game. I boarded a Clark streetcar as soon as I changed my clothes, and leaned against the rail of the rear platform, which was crowded with baseball enthusiasts going home. In my citizen’s attire none of the cranks knew me. They had evidently lost some money on the game and, as I had contributed more than anyone else to the Waterloo, I was the special target for their abuse. ‘That stiff they played on second base today made me sick,’ said one of the crowd. ‘What’s his name? McPhee? Yes, that’s it. Maybe he didn’t work the Cincinnati Club about wanting to keep books! He ought to have staved in Akron. He might be a good bookkeeper, but he is a rotten ballplayer!’ And so it went. I dropped off the car without making my identity known, and at that time fully coincided with their views that I could do better at bookkeeping than I could at ball playing.”

McPhee recovered quickly from his inauspicious beginning to help Cincinnati win the American Association championship. While he batted only .228, McPhee gave his early detractors a hint of his fielding prowess, leading the league’s second basemen in putouts, double plays, and fielding percentage. The Red Stockings’ major stars of their pennant-winning season were left-handed third baseman ‘Hick” Carpenter (.342), catcher-manager “Pop” Snyder (.291) and pitching ace Will White (40-12).

Although his Cincinnati teams would never again finish on top, McPhee went on to establish himself as the class of all nineteenth-century second basemen. McPhee led American Association second basemen in double plays every season the Red Stockings played in that league. In six out of eight seasons, McPhee led in fielding percentage. Playing bare-handed for most of his 18 seasons in Cincinnati, McPhee led American Association (1882-1889) and National League (1890-1899) second baseman in putouts eight times, assists six times, double plays eleven times, total chances per game six times, and fielding percentage nine times. McPhee remains the all-time leader among second basemen in putouts (6,552), and his 529 putouts in 1886 is the single-season major league record. He is also second in total chances (14,263) and fourth in assists (6,919).

As a hitter, McPhee was a consistent leadoff man with surprising power. He led the American Association in home runs with eight in 1886 (seven were inside-the-park homers). The following season, McPhee batted .289 with a league-leading 19 triples. He set a career-high in three-base-hits in 1890 with 22.

In that season, Cincinnati’s first in the National League, McPhee had perhaps his greatest day at the plate on June 28th when he hit 3 triples in a game against New York’s future Hall of Fame pitcher Amos Rusie (another future Hall of Famer, slugger Jesse Burkett, relieved Rusie midway through the contest, won by the Reds, 12-3).

McPhee stole 568 bases during his career, but that figure is misleading. No stolen base records were kept in the American Association before 1886, and from then until 1898, stolen bases were credited to base runners who went from first to third on a single or advanced an extra base on an out. McPhee was also a prolific run scorer with ten seasons in which he topped 100 runs. For his career, McPhee batted .272 with 2,258 hits.

McPhee’s offensive accomplishments aside, it was his bare-handed wizardry at second base that continued to set records and brought him fame. In an 1890 interview with the Cincinnati Enquirer, McPhee stated, “No, I never use a glove on either hand in a game. I have never seen the necessity of wearing one; and besides, I cannot hold a thrown ball if there is anything on my hands. The glove business has gone a little too far. It is all wrong to suppose that your hands will get battered out of shape if you don’t use them. True, hot-hit balls do sting a little at the opening of the season, but after you get used to it there is no trouble on that score.”

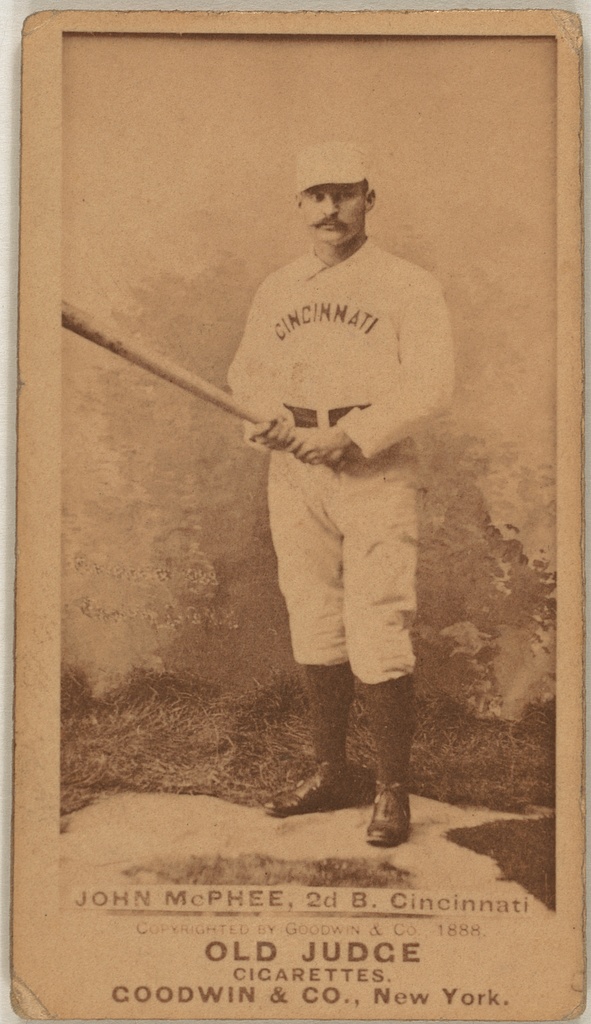

Standing 5’8″ tall and weighing just 152 pounds, the dapper-looking McPhee, complete with classic handle-bar moustache, was particularly adept at double-steal attempts with men on first and third. His quickness and savvy allowed him to decide whether to nail the man coming to second or return the ball to the catcher for a play on the man coming from third.

Earlier in McPhee’s career, “batsmen” were permitted to choose whether they wanted the pitcher to deliver a high or low ball. As a result, McPhee and other infielders found it relatively easy to tell where the ball would be hit. When this practice was ended in 1887, McPhee used his skills and knowledge to determine proper positioning for each batter. Also, because of the efforts of McPhee and two of his outstanding contemporaries, Fred Pfeffer and Fred Dunlap, the position of second baseman evolved in the 1880s from one of playing directly on or near the bag to placing themselves to the left, ranging towards first.

On the field and off McPhee was a gentleman. He was never fined or ejected from a game, and he was always sober and in playing condition. An 1897 ankle injury, the only serious one of his career, kept McPhee out of action for three months. Cincinnati fans and sportswriters staged a special benefit that raised $3,500 for him,

When he opened the 1896 season with an injured finger,. McPhee finally broke down and started to use a fielder’s glove. The result was his major league record fielding percentage of .978, not topped until 1925, when Sparky Adams fielded 983.

McPhee retired from active play after the 1899 season. He returned to manage the Reds to a last place finish in 1901. In 1902, the Reds showed some improvement, but McPhee resigned after only 65 games amid rumors that former Baltimore Oriole Joe Kelley was about to take his place. He continued to scout for the Reds until 1909 when he severed all his connections with baseball.

McPhee moved to Ocean Beach, California, a suburb of San Diego, and lived there in quiet retirement, all but forgotten by the baseball world. In the January 28, 1932 edition of The Sporting News, it was mentioned that McPhee was dead. This prompted a letter from Corwin Sage of Los Angeles in which he stated “John A. McPhee is an exceedingly lively corpse. We have been intimate friends for a great many years and exchange letters nearly every week. I wrote to him today (March 1. 1932). He is not as lively as in the days from ’82 to 1900, but still is able to give some of them pointers on how to play second base and might be able to line one to the fence if he was served a cold one… Bid cut out the article from The Sporting News and mailed it to me with the remark that it was not often a man had the pleasure of reading his own obituary. McPhee was one of the finest players and most perfect gentlemen the game has ever known.”

McPhee’s actual death occurred on January 3, 1943, at his home in Ocean Beach. In March, 2000, 57 years after his passing and a century after his playing career ended, Bid McPhee was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by a vote of the Veterans’ Committee. In addition to his considerable accomplishments as a ballplayer, McPhee’s Hall of Fame plaque notes his “sober disposition and exemplary sportsmanship.”

Sources

Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia-from the editors of Total Baseball.

David Falkner: Nine Sides of the Diamond-Random House, 1990.

Ralph C. Moses: “Bid McPhee”-The National Pastime #14, 1994, pages 48-50.

A. D. Suehsdorf: “Bid McPhee”-SABR Nineteenth Century Stars, 1989, page 91.

Total Baseball 7th Edition-Edited by John Thorn, Pete Palmer and Michael Gershman.

The Cincinnati Enquirer-April 12, 1890 and April 26, 1890.

The Sporting News-March 10, 1932 and January 3, 1943.

The Utica Globe-August 14, 1897.

Full Name

John Alexander McPhee

Born

November 1, 1859 at Massena, NY (USA)

Died

January 3, 1943 at San Diego, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.