Harry Wolter

Josefa Antonia Nepomucena Pascuala Estrada’s grandson played for six major-league teams from 1907 through 1917. Her son Manuel Adolfo Wolter was a stable keeper in Monterey, California. He married Lucretia “Lucy” Little and the two had seven children – Charles, Mary Mamie, Lucy Eleanor, Manuel, Milton John, Grace, and Harry. Their youngest, Harry Meiggs Wolter, was born in Monterey on July 11, 1884. By 1900, Manuel was listed in the census as working with the “night police.”1

Josefa Antonia Nepomucena Pascuala Estrada’s grandson played for six major-league teams from 1907 through 1917. Her son Manuel Adolfo Wolter was a stable keeper in Monterey, California. He married Lucretia “Lucy” Little and the two had seven children – Charles, Mary Mamie, Lucy Eleanor, Manuel, Milton John, Grace, and Harry. Their youngest, Harry Meiggs Wolter, was born in Monterey on July 11, 1884. By 1900, Manuel was listed in the census as working with the “night police.”1

Harry went to Monterey High School and attended Santa Clara University in the California city of the same name, graduating with the class of 1906. His first foray into professional baseball was in 1905, at age 20, when he played briefly for both the San Jose Prune Pickers (California State League) and Seattle in the Pacific Coast League. He pitched in three games (2-1) for San Jose and collected 11 at-bats for Seattle without a hit.

He pitched for the Fresno Raisin Eaters of the PCL in 1906 and was 12-21 with a 3.22 ERA, his won-loss record more or less matching the last-place team’s 64-120. He also played outfield and appeared in 149 games, batting .307. “Wolter is young and has no bad habits,” reported the Los Angeles Times, saying that he was “a good man for some big team to land.”2

In 1907, Wolter played for four teams – including three in the major leagues. He started with Cincinnati and made his debut for the Reds in New York on May 14 as a late-inning replacement in right field. He played in only four games for Cincinnati, with two hits (.133) and one run batted in as an outfielder. On June 13, he was purchased by Pittsburgh, but he only played in one game for the Pirates, with one at-bat and nothing to show for it.3 But he’d worked for Pittsburgh as a pitcher that day, throwing the last two innings of the June 17 home game and giving up two runs (one earned) on three hits and two walks. The Phillies won, 7-3. Manager Fred Clarke didn’t really have a need for him and so made him available to the St. Louis Cardinals.

On July 4, the Cardinals purchased his rights and he played in 16 games. As a pitcher, he was in three (0-2 in 23 innings with a 4.30 ERA), but as an outfielder and pinch-hitter, he hit for a .340 average with six RBIs in 47 at-bats. After the National League season ended, he joined San Jose again for some California State League baseball, helping shut out Sacramento on October 19 and continuing on to play the longer West Coast season.4 He appeared in four games.

St. Louis sold his 1908 contract to St. Paul, but he refused to go, re-joining the “outlaw” California State League instead. Sporting Life characterized him as “drifting around among the minors without an engagement.”5 Wolter played again with San Jose and hit .339 in 74 games, but his pitching dominated the league: he was 24-2, at one point winning 17 consecutive games. The team finished second to Stockton.

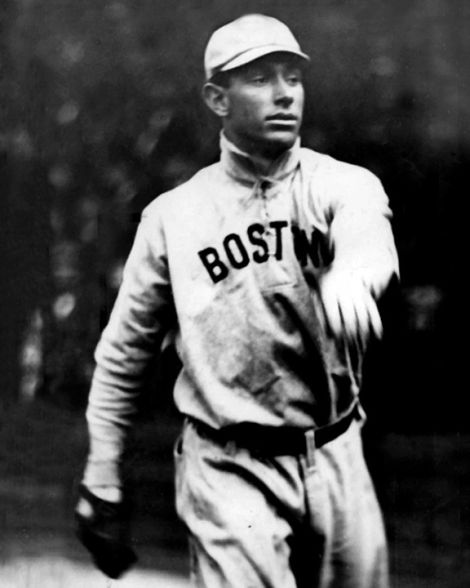

The Boston Red Sox bought his contract from San Jose “for a big price” according to the Boston Herald.6 Wolter was 5-feet-10 and weighed 175. Before he could join the Red Sox, he had to pay a $50 fine for failing to report to St. Paul in 1908.7 He paid up, applied for reinstatement, and his application was approved.8

Both he and pitcher Frank Arellanes left San Jose for spring training, where Harry was one of nine “Harrys” with the Sox. He made the team, and early on was pressed into duty playing first base when Jake Stahl had to leave the club for a while due to the death of his daughter. Manager Fred Lake was prepared to use him in the outfield, too. He played 17 games at first base, 11 as pitcher, and 9 in the outfield. He was 4-4 on the mound with a 3.51 ERA and he hit .240 with two homers and 10 RBIs. He’d started out very strong, but lost considerable weight as the season progressed and tailed off. He was, however, given a salary increase for 1910.

Over the wintertime and in the early spring, he umpired in some college games in California.9 He was placed on waivers, and the New York Highlanders paid Boston the $1,500 waiver price on January 15, adding a player who served them well. The Boston Journal ran a photo of him on the 17th, saying he would pitch for the Highlanders. As it happens, the games he pitched for the 1909 Red Sox were the last ones he pitched in the majors.

Wolter played in 135 games in 1910 and probably would have played in more but for a broken finger suffered while trying to field a Ty Cobb drive in the July 26 game against the Tigers. He hit .267 with 42 RBIs. Typically hitting leadoff, he scored 84 runs. Hal Chase took credit for New York acquiring Harry to play right field. “I have known Wolter since we were boys together in California, and I consider him a high-class, all-around player. He is not so much of a pitcher, but he can play the infield and outfield, can hit the ball, and he is a very fast runner.”10

After the 1911 season, Wolter accepted an offer to coach the Santa Clara University baseball team, which he did until it was time to report for duty in the springtime. There was a disagreement with the president of the university after Wolter suspended a player and there were reports that Wolter resigned. Matters were worked out and he wrapped up his time with the team and left for spring training with New York.

1912 was a difficult year. Very early on, on May 18, he dislocated his kneecap sliding into second base. It was more serious than first thought – it was soon determined he had broken the leg in two places, which pretty much relegated him to the bench for most of the year. He appeared in only 12 games, though he hit .344 and scored eight runs in his limited action. He drove in one. He left the team in late August and went home. He did some scouting later that year for New York.11 Late in the fall, he began playing some baseball around Monterey and reported that he had completely recovered.

He traveled back across the U.S. and even further east to Bermuda to join in spring training with the Yankees, and got into 127 games during the 1913 season, but his batting average dropped to .254. His stolen bases totals were down substantially, and so were his runs scored (53); he had a career-best 43 RBIs, however.

On April 20, 1914, Wolter married Miss Irene Hogan, “a society belle” of Palo Alto.12 He had been expecting to return to New York and when he was informed that New York had released him to the Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels in February, he was “greatly surprised and nettled.” He said, “It is a clear case of railroading. (New York owner) Frank Farrell never asked waivers on me and is trying to send me to the minors without giving me a chance to get on with some other American League club. I will sign with the Angels for the same salary I received from the New Yorks, but will not accept any contract which calls for a cent less, and unless these terms are met I will jump to the Federal League.”13 The Indianapolis ballclub in particular had made him an offer.

In the end, he stuck with Los Angeles and played there from 1914 through 1916, exclusively as an outfielder. He led the league with 802 at-bats in 1914 and with 263 base hits. In both 1914 and 1916 he led the league in triples. He led the league twice in batting, with a .328 average in 1914 and a .359 average in 1915, both for manager Frank “Pop” Dillon. He even won a $50 suit of clothes from team owner John Powers for having driven in 40 runs in a stipulated time period in 1915.14 He missed the last several weeks of the 1915 season due to an injury. In 1916, he hit .296 for new manager Frank Chance. (Chance had been his manager with the Yankees in 1913.) His average wasn’t as high, but the 1916 Angels won the PCL pennant. There is some indication that Wolter had hoped to be named Angels manager, but he had not been.

Wolter kept busy in the offseasons. In late October 1914, the day after the Coast League season ended, he returned to San Jose to organize his winter league team. And he coached again for Santa Clara. There had been rumors that he would be returning to New York, and of both the Cardinals and the White Sox trying to entice him, but he stayed with Los Angeles those three years. In December 1915, he was hired as baseball coach for Stanford.15

Wolter’s contract was sold to the Chicago Cubs on August 25, 1916. The Cubs asked for immediately delivery but Chance wasn’t prepared to let him go while the Angels were still in the hunt for the flag. He stayed on the Coast.

He was “the sensation of the camp” when the Cubs trained at Pasadena in the spring of 1917, and was considered “the brainiest outfielder in the league.”16 He played the full season for the Cubs, appearing in 117 games with an even 400 plate appearances. He hit for a .249 average, scored 44 runs, and drove in 28.

In the offseason, he did war-related work serving as a tool dresser working in the oil fields around Bakersfield.17

The Cubs wanted to cut his salary by $1,300 in 1918, so he returned the proffered contract unsigned. He had hoped to become manager of the Sacramento Senators and had applied for the position. It went to Bill Rodgers. There was a deal in the works between the San Francisco Seals and the Cubs but at the eleventh hour, Sacramento stepped in and made the deal to get Wolter.18 It was apparently a straight cash transaction, and it was apparently more like 11:56, not just the eleventh hour. A story in the April 17 San Jose Evening News says that Rodgers’ telegram beat the Seals’ Charlie Graham’s by four minutes.

He hadn’t gotten the managerial position. But he did play outfield in 73 games. (The Coast League season ended in July due to the war.) Harry hit only .221, perhaps in part because he’d been ill with the grippe at the start of the season. He also pitched a total of one inning, without giving up either a walk or a hit. He worked as a truck driver for Standard Oil. When he registered for the draft in September 1918, he gave that as his occupation.

He played for Sacramento again in 1919, in 158 games, and this time he hit .329.

In December 1919, he was traded to Seattle for Pete Compton. It took him a while to sign; Wolter was, explained the Seattle Daily Times, “a chronic spring holdout.”19 It seems that Seattle caved. He hurt his knee early on, and then was struck in the face by a ball that caromed off the batting cage during batting practice, an injury so severe he had to take a little time off.

On July 15, 1920, he was traded to San Francisco for Phil Koerner. The Seals were the team he’d really wanted to play for, but he was only there for about a month before he was dealt, on August 19, to the Salt Lake City Bees. In 145 games, he hit a combined .266 for the three PCL clubs.

He retired from the game. He played some in the San Joaquin Valley League, outside of organized baseball, and at the time of the 1920 census, Harry and his wife Irene lived in Sacramento and he was listed as a laborer for an unnamed oil company.

In 1923, he found the position he kept for the rest of his working life. He became the head baseball coach at Stanford University and served until 1949. The Wolters were living in a $20,000 home in Palo Alto by the time of the 1930 census. They appear to have never had children.

There were just a few other times he was active in the game. In late 1926, he led a baseball tour of Japan and in 1927, when he was 42, he took the position of manager for the Logan Collegians in the Class C Utah-Idaho League. He pitched (9-6) and played some at first base and hit .294. The following year, he led the Stanford baseball team on a tour of Australia.

Harry died of heart disease at his home on the Stanford campus in Palo Alto on July 6, 1970.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Wolter’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Carlos Bauer for supplying California State League statistics.

Notes

1 Manuel Adolfo Wolter had been born of German father Charles Luis Wolter and California mother Josefa Antonia Nepomucena Pascuala Estrada in 1847. Lucretia Catherine Little was born in California of two parents from New York, in 1854. The couple married in 1874.

2 Los Angeles Times, September 8, 1906.

3 The Chicago Tribune reported the sale on June 14.

4 San Jose Mercury News, October 20, 1907.

5 Sporting Life, March7, 1908.

6 Boston Herald, February 18, 1909 and Boston Globe, February 19.

7 Boston Herald, March 19, 1909.

8 Sporting Life, March 27, 1909. The publication reported that on February 13, the National Commission had fined St. Louis $515 for selling its claim on the “ineligible pitcher” to the St. Paul club “without first having secured his reinstatement for playing with the outlaw California League.” See Sporting Life, January 8, 1910.

9 Sporting Life, March 26, 1910.

10 Sporting Life, February 12, 1910.

11 San Jose Mercury News, September 14, 1912.

12 Sporting Life, May 23, 1914.See also San Jose Evening News, April 20, 1914.

13 Sporting Life, February 21, 1914.

14 San Jose Mercury News, July 6, 1915.

15 San Jose Mercury News, December 12, 1915 and February 10, 1916. He had to resign the position in mid-March to rejoin the Angels.

16 Sporting Life, March 24 and March 17, 1917.

17 San Diego Evening Tribune, February 27, 1918.

18 San Jose Evening News, April 9, 1918.

19 Seattle Daily Times, February 19, 1920.

Full Name

Harry Meiggs Wolter

Born

July 11, 1884 at Monterey, CA (USA)

Died

July 6, 1970 at Palo Alto, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.