Roy Sievers

Overcoming potentially career-ending shoulder injuries in the early 1950s to develop into one of the most feared sluggers of his era, Roy Sievers became just the 18th player to hit 300 home runs. With a powerful and graceful swing that Casey Stengel called “one of the sweetest,” 1 Sievers, known as Mr. Clutch for his late-inning heroics, hit almost a quarter of his home runs in the eighth inning or later, including nine walk-off blasts. The recipient of the inaugural AL Rookie of the Year Award (1949), Sievers also hit ten grand slams and ten pinch-hit home runs.

Overcoming potentially career-ending shoulder injuries in the early 1950s to develop into one of the most feared sluggers of his era, Roy Sievers became just the 18th player to hit 300 home runs. With a powerful and graceful swing that Casey Stengel called “one of the sweetest,” 1 Sievers, known as Mr. Clutch for his late-inning heroics, hit almost a quarter of his home runs in the eighth inning or later, including nine walk-off blasts. The recipient of the inaugural AL Rookie of the Year Award (1949), Sievers also hit ten grand slams and ten pinch-hit home runs.

Roy Edward Sievers was born on November 18, 1926, in St. Louis to Walter and Anna Sievers. Born in 1900, Anna (née Hirt) was a native-German speaker who emigrated from Hungary in 1909 and settled in St. Louis. Walter, born in 1892, lived his entire life in St. Louis and married Anna in 1917. They had four boys, Walter, Russell, William, and Roy, the youngest. Employed by an iron supply company, Walter “Skinny” Sievers played sandlot baseball and had an unsuccessful tryout with the Detroit Tigers before serving in World War I.2

Residing just three blocks away from Sportsman’s Park, where both the Cardinals and Browns played, Roy was literally raised with major-league baseball in his back yard. In a neighborhood defined by baseball, he and his brothers played whenever they could. “We were all ballplayers,” his father said. “None of us had to teach Roy how to play; he came by his baseball naturally. He has good wrists, a fine arm, and could run.”3

At Beaumont High School Roy was all-district in basketball and baseball for three years. Tall (6-feet-1) and lanky, Sievers was nicknamed Squirrel because of his tendency to be around the cage on the hardwood court. He could have played college basketball; however, St. Louis was a baseball town and Sievers’ passion was on the diamond. His high-school baseball team, coached by Ray Elliott, boasted four players who later played for major-league teams: Bobby Hofman, Jim Goodwin, Jack Maguire, and Sievers. Earl Weaver, future manager of the Baltimore Orioles, was on the junior varsity squad.

Sievers also played for Stockham, coached by Leo Browne, in the city’s highly competitive American Legion league. Playing primarily in the outfield, he was attracting scouts by the age of 16. “I was scouted mainly by the St. Louis Cardinals,” Sievers told the author. “Wally Shannon scouted me for three years while I was in high school. The Browns had some scouts at my games, too.”4 Browns scout Lou Magoulo, who later made his fame with the New York Yankees, persuaded Jack Fournier, director of the Browns’ farm system, and Browns executives Bill and Charlie DeWitt (later owners of the club) to sign him. “Jack Fournier called my house and we ended up signing with the Browns, but he never saw me play,” Sievers said. He signed with the Browns in 1945. His signing bonus: a pair of baseball shoes! Because of the Cardinals’ deep and extensive farm system, in which players were hoarded, “I thought I had a better chance playing with the Browns than with the Cardinals,” Sievers explained.

After being drafted and serving as an Army MP, Sievers reported to the Browns’ spring-training camp in 1947 fully expecting to make the team. Assigned to the Hannibal (Missouri) Pilots of the Class C Central Association, Sievers remembered, “I played outfield and third base for Hannibal. I had a great year in that league [he led the league with 34 home runs], and I thought it’d be easy, but I found out it wasn’t.” In the offseason, Browns vice president James McLaughlin touted Sievers as “probably the greatest player ever to come out of St. Louis and … our outstanding prospect.”5 After another spring training with the Browns, Sievers was assigned to Class A, Elmira in the Eastern League; he struggled against more experienced competition and was demoted to the Springfield (Illinois) Browns in the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League. Despite missing almost a month of the season, Sievers challenged for the league’s home-run title, eventually settling for third place behind teammates Don Lenhardt and John Novosel.

After hitting just 63 home runs in 1948, the Browns were in desperate need of a power hitter for 1949. The right-handed Sievers, proclaimed by The Sporting News as a “can’t miss prospect,”6 made the team. “I should have made the Browns in 1947 and 1948,” he said. “I had two great springs, but of course they always tell you that you need more seasoning, so they sent me down.” Playing for the $5,000 major-league minimum, Sievers debuted on April 21, 1949, as a pinch-hitter in the ninth inning against Cleveland and struck out.

Breaking into the starting lineup in the 12th game of the season, Sievers displayed quickness in the outfield and patience at the plate with a team-high .398 on-base percentage. He hit his first major-league home run on May 14 against Fred Hutchinson in a victory over the Tigers. With a career-best .306 batting average, 16 home runs (which led all rookies), and 91 runs batted in (ranking sixth in the league), Sievers received the inaugural American League Rookie of the Year Award. “He has great power, can run like a deer and is one of the sweetest flyhawks in the league,” said his manager, Zack Taylor.7 Sievers’ “rise from obscurity” drew attention from other ballclubs, which attempted to obtain him from the perpetually financially straitened Browns.8 Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics reportedly offered the Browns $200,000 for him.9

When the season ended, Sievers augmented his income by participating in his first barnstorming tour, traveling throughout the Midwest and Great Lakes region on a team led by Detroit pitcher Dizzy Trout.10 Owing to his popularity, Sievers regularly traveled with barnstorming teams throughout the 1950s. With Willie Mays, he headlined a team that traveled to Mexico in 1958.11

Sievers played in only 247 games in the next four years (1950-1953) which were marked by disappointment, career-threatening injuries, and, finally, resiliency. He endured a torturous “sophomore jinx” and a long slump to start the 1950 season, and lost his starting position. His struggles at the plate (he was batting just .196 on July 2) baffled manager Taylor, who said in June, “Sievers is too good to flop.”12 Finishing the season with a .238 batting average and just ten home runs, Sievers began the 1951 season with a failed experiment at third base. As his hitting woes continued, he became the target of hostile fans. “I didn’t mind the razzing,” he Sievers said. “Those fans pay to get in and have the right to holler.”13 In mid-June, batting.225 with one home run in 99 at-bats, Sievers was demoted to San Antonio of the Texas League. On August 1 he suffered a season-ending injury when he fell awkwardly on his shoulder, separating it. In spring training the following season, Sievers dislocated his arm and strained the nerves in his shoulder while making a throw. He had potential career-threatening (and experimental) surgery performed by Dr. George Bennett at Johns Hopkins Hospital to repair the damage and missed most of the season, returning in September for 11 games.

With just one home run in the previous two years and a sore shoulder that prohibited him from throwing overhand, Sievers began the 1953 season with his career in jeopardy. “I worked with Bob Baumann [the Browns’ trainer] every day at Saint Louis University, where he was also a trainer for the college baseball team,” Sievers said. “Without him I don’t think I could have been able to stay in baseball.”

Bill Veeck, who bought a controlling interest in the Browns from the DeWitt family in 1951, thought that to save his career, Sievers should play first base. Sievers said Veeck hit him groundballs “day-in and day-out. … That’s how I learned to play first base.” Though Sievers was batting just .162 on June 9, and The Sporting News labeled him a “major disappointment,” Veeck and new Browns manager, Marty Marion, exercised patience. Sievers began using one of Cardinal infielder Red Schoendienst’s bats. “It [had] a skinnier handle … and [felt] a lot better to swing than my old bat,” he said.14 He batted .308 the rest of the season to finish with a respectable .270 average while playing exclusively at first base. (But he lacked power, clubbing just eight home runs.)

The 1953 offseason was tumultuous for Sievers. Veeck sold his controlling interest in the Browns to new owners who moved the team to Baltimore. Before Sievers donned an Orioles uniform, he was traded to the Washington Senators for outfielder Gil Coan. It was a blessing in disguise. “I was hoping I’d stay in Baltimore,” he said. “For some reason, they thought I couldn’t throw no more. Jimmy Dykes, the manager of the Orioles, thought they should get rid of me. They traded me to the Washington Senators and it turned out to be my biggest break.” Based on a rumor that Sievers’ shoulder had not responded to rehabilitation and that he could never play in the outfield again, the trade turned out to be one of the most lopsided in baseball history.15 Sievers developed into an All-Star; Coan managed just 110 more hits before leaving the major leagues.

In his six seasons with the Senators (1954-1959), Sievers became one of the American League’s most feared home-run hitters, averaging 30 a year, and endeared himself to fans and the city; however his future was not that clear when he began spring training in 1954. “When I got to Washington, I asked Bucky Harris where I am going to play,” he said. “I couldn’t play in the outfield, but he said, ‘You just gotta get to the ball real quick and throw it real quick, because we need your big bat in the lineup.’ So that’s what I did.” Playing 133 games in left field against his surgeon’s advice, Sievers still possessed his speed, and to lessen the pressure on his shoulder, he usually threw the ball with a side-arm delivery to the shortstop.16

In his six seasons with the Senators (1954-1959), Sievers became one of the American League’s most feared home-run hitters, averaging 30 a year, and endeared himself to fans and the city; however his future was not that clear when he began spring training in 1954. “When I got to Washington, I asked Bucky Harris where I am going to play,” he said. “I couldn’t play in the outfield, but he said, ‘You just gotta get to the ball real quick and throw it real quick, because we need your big bat in the lineup.’ So that’s what I did.” Playing 133 games in left field against his surgeon’s advice, Sievers still possessed his speed, and to lessen the pressure on his shoulder, he usually threw the ball with a side-arm delivery to the shortstop.16

Mired in a slump to begin the season (he was hitting just .198 on May 15), Sievers became acclimated to Washington’s cavernous Griffith Stadium and finished with a Senators-record 24 home runs. It was the first of his four seasons with more than 100 RBIs for the sixth-place Nats. His 1955 season followed the script from the previous campaign. Plagued by a two-month batting slump (he was hitting .197 on June 23), Sievers raised his average to .271 by the end of the year, set another Senators record with 25 home runs, and batted in 106 runs.

With its irregular dimensions, Griffith Stadium was one of the largest in baseball and boasted a 388-foot power alley in left field, a sloping 408- to 421-foot center field, and a right-field power alley measuring 373 feet with a 31-foot-tall concrete fence.17 When Calvin Griffith took over the team after his uncle Clark Griffith died in 1955, he decided to shorten the outfield to generate more offense and sell more tickets.

Left field, shortened to 350 feet, was christened Sieversville in honor of Roy’s mammoth blasts.18 Sievers responded by hitting 29 home runs, breaking the club record again, and forged with Jim Lemon (27 home runs) the AL’s most potent long-ball threat behind the Yankees’ Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra. The Senators set a new team record with 112 home runs, but limped to a seventh-place finish at 59-95 and struggled at the gate, drawing fewer than 432,000 fans for the season. He was named to the American League All-Star team for the first time. As the Senators’ most productive hitter since the days of Goose Goslin, and Joe Cronin in the 1920s and early 1930s, Sievers was again coveted by other teams, and rumors swirled that he would be shipped away to help ease the Senators’ financial difficulties.

Asked to explain his development as a power hitter in Washington, Sievers responded that he was healthy, his shoulder felt fine, and the managers had confidence in him. “I was able to play every day and work on my hitting.”

Sievers possessed a smooth, graceful swing, which he said he learned from watching his favorite player, Joe Medwick, at Sportsman’s Park, and then practicing with his father.19

Sievers served as the swinging double for Tab Hunter, who portrayed the fictional baseball player Joe Hardy in the 1958 film Damn Yankees. “He [Sievers] doesn’t chase bad pitches,” said Detroit Tigers Hall of Famer Charlie Gehringer.”20 Sievers had a simple philosophy on hitting: “My dad was a pitcher and a pretty good hitter,” he told the author. “He told me, ‘Son, when you see the first good pitch to hit, hit it.’ And I did.” Sievers possessed a discerning eye and struck out more than 80 times in a season just twice in his career. “Batting coaches didn’t help too much,” Sievers said. “We players helped each other. Jim Lemon and I were roommates and we talked about hitting all the time.”

Avoiding his traditionally poor start, Sievers hit four home runs and drove in 12 runs in his first eight games of 1957, including a dramatic ninth-inning walk-off home run to defeat the Yankees. In mid-July he hit ten home runs in 17 games, including an American League record six games in a row with a homer. It was almost seven. Playing the Tigers, “I hit it pretty good in my last at-bat and I thought it was going out of the park, but the center fielder [Bill Tuttle] jumped up and caught the ball against the fence.” Battling Mantle and Ted Williams for the home-run crown all season, Sievers beat them out with 42 round-trippers and 114 runs batted in, both career highs. He became the first player in major-league history to lead his league in home runs and RBIs while playing for a last-place team.

Despite the Senators’ poor record and attendance (less than 458,000 for the season), the team honored Sievers on September 23. “Calvin Griffith gave me a night in Washington,” he said. “They presented me with an automobile and Vice President Richard Nixon was there. According to him, I was his favorite ballplayer and President Eisenhower liked Jim Lemon.” After the season Sievers was a highly sought-after speaker and guest at political and high-society gatherings in Washington.

While Sievers became the highest-paid Senator ever, signing a reported $36,000 contract in 1958, newspapers speculated about his imminent trade.21 In an interview with the author, Sievers said the trade rumors never bothered him, but noted, “One rumor that I hoped would come true was to go to the Boston Red Sox.” He thought a trade between the two clubs was unlikely because Red Sox general manager Joe Cronin and Calvin Griffith were brothers-in-law. “I used to talk to Ted Williams and he’d say, ‘Kid, if we could get you, we’d win some pennants.’ That was the one place I really wanted to play.” After Sievers almost repeated his spectacular 1957 season by hitting 39 home runs and driving in 108 runs for the last-place Nats, the team reportedly turned down a $250,000 offer for him.22

Beset by nagging injuries in 1959, Sievers batted just .242 with only 21 home runs and 49 RBIs. With the rise of 23-year-old Harmon Killebrew (who hit 42 home runs that season to tie Sievers’ team record), and 24-year-old Rookie of the Year Bob Allison with 30 home runs, Sievers seemed to be expendable to Griffith, who sought to relocate his franchise to the Minneapolis-St. Paul area during the frenzied rush of team shifts westward. In his ten years with the Browns and Senators, Sievers played on weak pitching teams that finished in seventh or eighth place nine times, yet the soft-spoken, courteous, easy-going Sievers was a consummate team player who was never ejected from a game during his playing career.

After the White Sox’ surprise pennant-winning season in 1959, owner Bill Veeck wanted a home-run punch to support the light hitting Go-Go Sox. He mortgaged the team’s future by trading youngsters Earl Battey, who developed into an All-Star catcher for the Twins, dependable first baseman Don Mincher, and $150,000 for the 33-year-old Sievers during spring training. Manager Al Lopez preferred power-hitting first baseman Ted Kluszewski, and Sievers was relegated to the bench to begin the season for the first time in seven years. Platooning with Kluszewski and seeing some duty as a pinch-hitter, Sievers struggled, batting just .182 with three home runs at the end of May. When Kluszewski was injured in early June, Sievers had a chance to play every day and soon found his stroke. From June 23 to July 18 he had a 21-game hitting streak, the longest in the major leagues that year. In July he enjoyed arguably the best month of his career, hitting 12 home runs, driving in 30 runs, and batting over .400. With the White Sox leading the AL by 1½ games at the end of July, Sievers was considered the front-runner for Most Valuable Player. “I blame myself for not playing Roy Sievers every day,” said manager Lopez. “I didn’t realize that Sievers must play every day to keep his timing.”23 The White Sox cooled off in August and September, finishing third. Sievers had made a seamless transition to his new team and for the first time in his career played on a team with a winning record. He batted .295, tallied 28 home runs, and drove in 93 runs in 1960 despite playing in only 127 games.

With five position players at least 33 years old, the White Sox fielded the oldest team in baseball in 1961, yet led the AL in batting and stolen bases for the second year in a row. Hitting in his traditional cleanup spot, Sievers posted almost identical numbers from the previous year (27 HRs, 92 RBIs, and a .295 BA). The White Sox were never in contention, and when the ailing Veeck sold his controlling interest in the team to Arthur and John Allyn, they traded Sievers in the offseason to the Philadelphia Phillies for pitcher John Buzhardt and infielder Charley Smith.

Sievers arrived on a young, promising Phillies team poised to contend in the National League over the next few years. As the only regular older than 27, the 35-year-old Sievers provided the Phillies with veteran leadership and confidence. With Don Demeter, Tony Gonzalez, Johnny Callison, and Sievers, the Phillies boasted four players with at least 20 home runs for the first time in their history and experienced a dramatic jump from a record of 47-107 to 81-80 in the first year of expansion in the National League. Initially, Sievers voiced concern about switching leagues, saying, “It will take a while to know how they pitch me and the difference in the strike zone. I understand they call more low pitches in the National League.”24 Almost as if on cue, he struggled mightily, needed five weeks to rap his first extra-base hit, and was batting .190 on June 13 with just five home runs. Then he hit his stride. For the rest of the season he was the Phillies’ most effective hitter, belting 16 home runs, driving in 59 runs, and batting .297.

During spring training in 1963 Sievers suffered a fractured rib when he was hit by a Jim Maloney fastball and was hampered to begin the season. Showing signs of slowing down, the 36-year-old Sievers still played 126 games at first base, but his streak of nine consecutive seasons of 20 or more home runs was snapped when he finished with 19 to go along with 80 RBIs in what turned out to be his last season as an everyday first baseman. On June 19 Sievers hit his 300th home run, a walk-off two-run blast off Roger Craig to beat the Mets, 2-1, in Philadelphia.

Bothered by a strained calf, Sievers saw limited playing time for the Phillies during their phenomenal start in 1964. Batting just .183, he was sold on July 16 for the waiver price of $20,000 to the expansion Washington Senators. Used primarily as a pinch-hitter, Sievers belted four home runs in 58 at-bats with the Senators. With a .172 batting average, he was put on waivers at the end of the season.

The Senators re-signed Sievers in April 1965 but was released in May after just 21 at-bats. He retired in midsummer after unsuccessful tryouts with the White Sox and Cardinals, ending a 17-year career in the major leagues.25 In 1,887 games, the four-time All-Star batted .267, drove in 1,147 runs, and hit 318 home runs.

In 1966 Sievers coached for the Cincinnati Reds under manager Don Heffner. His contract was not renewed for 1967. Sievers managed for two years in the New York Mets organization, leading Williamsport to a second-place finish in the Eastern League in 1967 but was let go the following year after his Memphis Blues team lost 27 games by one run in the Texas League. In 1969 and 1970, he piloted the Burlington Bees, an Oakland farm club in the Midwest League, to consecutive losing seasons and was fired. “I found out that I was only making about $8,000 a year and I couldn’t raise my family on that,” Sievers said.

Sievers returned to St. Louis with his wife Donna and their three children. Donna Colburn was from Springfield, Illinois. Roy met her when he played there in 1949. After baseball, “I went to work for Yellow Freight Systems in St. Louis and worked there for 18 years. I got fired and told my wife, ‘It’s time to retire.’ ” Sievers participated in annual gatherings of the St. Louis Browns and various baseball player reunions. He was elected to the St. Louis Browns Historical Society Hall of Fame, and in 2013 was still following the game closely from his home in St. Louis. Reflecting on his career, and his prime years playing for talent-poor clubs like the Browns and Senators, Sievers said “I don’t regret any time in the big leagues. It was just super.”

He died at age 90 on April 3, 2017.

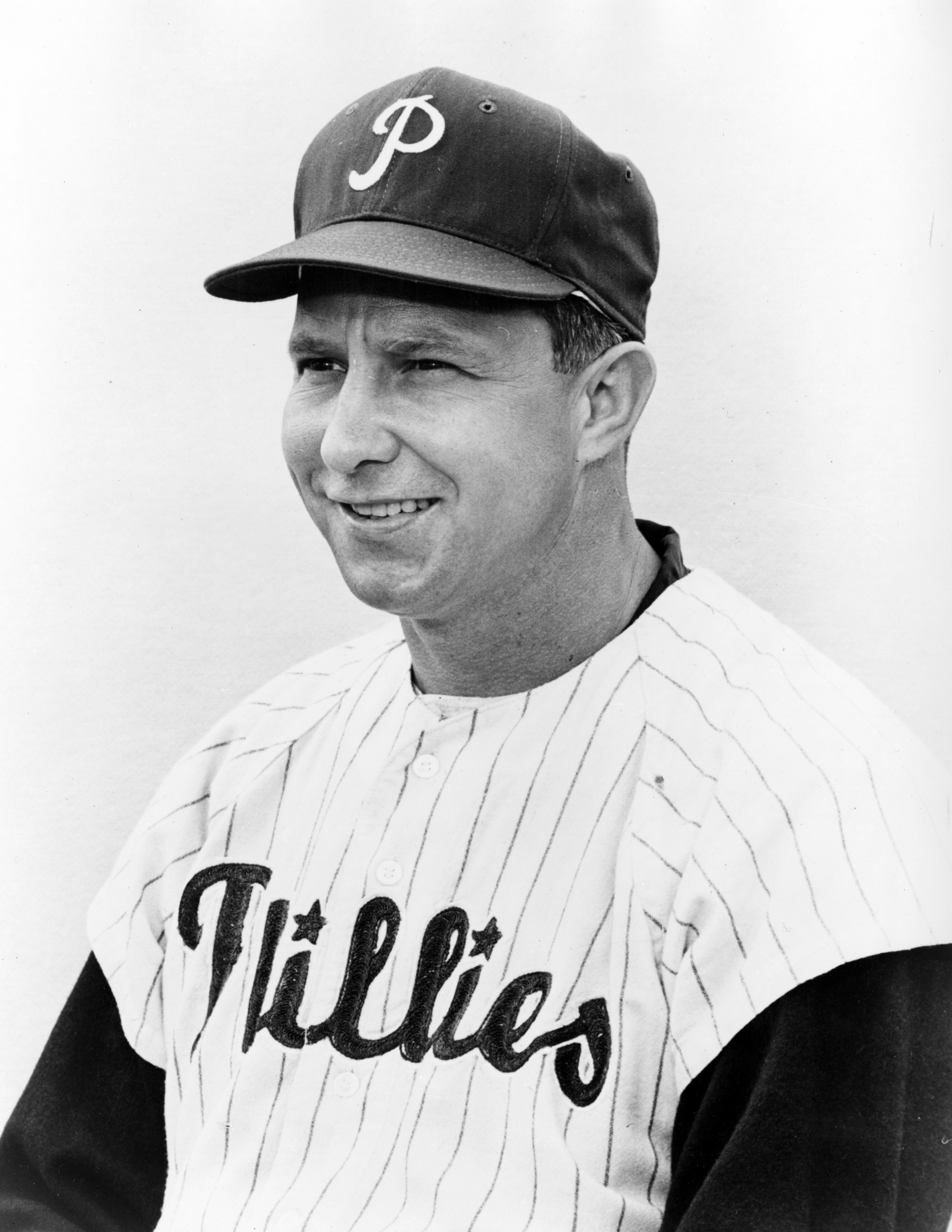

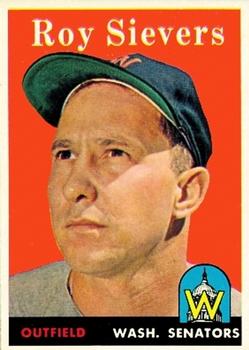

Photo credits

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 “Events and Discoveries,” Sports Illustrated, October 7, 1957. SI Vault. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/

2 David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of America. Q-Z. (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000), 1415.

3 The Sporting News, October 26, 1949, 6.

4 The author expresses his gratitude to Roy Sievers, who was interviewed on May 7, 2012. All quotations from Mr. Sievers are from this interview unless otherwise stated.

5 The Sporting News, January 21, 1948, 15.

6 The Sporting News, September News, September 1, 1948, 12.

7 The Sporting News, October 5, 1949, 13.

8 The Sporting News, June 28, 1950, 18.

9 The Sporting News, December 7, 1949, 18.

10 The Sporting News, September 7, 1949, 29.

11 Hal Hendrix. “Mexicans Warmed by Movie,” Miami (Florida) News, October 12, 1958, 112.

12 The Sporting News, June 28, 1950, 18.

13 The Sporting News, July 4, 1951. 10.

14 The Sporting News, July 29, 1953, 14.

15 The Sporting News, March 3, 1954, 9.

16 The Sporting News, March 31, 1954, 11.

17 John Thorn and Peter Palmer, eds., Total Baseball. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Baseball, 3rd ed. (New York: Harper, 1993, 139-40).

18 The Sporting News, September 5, 1956, 19.

19 The Sporting News, October 26, 1949, 6.

20 The Sporting News, July 3, 1957, 21.

21 The Sporting News, March 5, 1958, 4.

22 The Sporting News, December 10, 1958, 17.

23 The Sporting News, July 27, 1960, 16.

24 The Sporting News, December 13, 1961, 28.

25 Norman Macht, “Roy Sievers: A Forgotten Power Hitter of the 1950s,” Baseball Digest, July 1990, 58.

Full Name

Roy Edward Sievers

Born

November 18, 1926 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

April 3, 2017 at Spanish Lake, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.