Dick Hoblitzell

An intelligent player whom both teammates and opponents respected, 29-year-old first baseman Dick Hoblitzell opened the 1918 season as the Red Sox’ captain and cleanup hitter, but an early-season slump and his June induction into the Army Dental Corps marked an inglorious end to an otherwise distinguished 11-year career in the major leagues. Though he spent the more productive early part of his career with the Cincinnati Reds, “Hobby” looked back most fondly on his time with three World Champion teams in Boston, and in later years he kept in touch with Red Sox teammates Larry Gardner, Harry Hooper, Herb Pennock, and Tris Speaker.

An intelligent player whom both teammates and opponents respected, 29-year-old first baseman Dick Hoblitzell opened the 1918 season as the Red Sox’ captain and cleanup hitter, but an early-season slump and his June induction into the Army Dental Corps marked an inglorious end to an otherwise distinguished 11-year career in the major leagues. Though he spent the more productive early part of his career with the Cincinnati Reds, “Hobby” looked back most fondly on his time with three World Champion teams in Boston, and in later years he kept in touch with Red Sox teammates Larry Gardner, Harry Hooper, Herb Pennock, and Tris Speaker.

The middle of three sons, Richard Carleton Hoblitzell was born on October 26, 1888. His mother, the former Laura Alcock, was of English descent, while his father, Henry Hoblitzell, whose ancestors hailed from the oft-disputed Alsace-Lorraine region, was part German, Swiss, and French. The Hoblitzell surname was a source of confusion throughout Dick’s baseball career; Dick himself, however, consistently spelled it with two l’s. Dick’s older brother, William, and his younger brother, Clinton, both had blue eyes and light-colored hair, but Dick had dark brown hair, brown eyes, and a darker complexion than his brothers.

The Hoblitzell boys were born in the Ohio River village of Waverly, in West Virginia’s oil region, and the family owed its middle-class existence to Henry’s work in the oil fields. When Dick was eight years old his mother died and the family moved a short distance downriver to Parkersburg, West Virginia. Dick captained the Parkersburg High School football team during his freshman and sophomore years, and it was around that time that he gained his first professional baseball experience. As Dick told the story, Henry Hoblitzell had remarried a woman from France and Dick was not getting along with his stepmother, so he accepted an invitation to join a barnstorming Bloomer Girls team to get away from her. Henry ended up having to retrieve him somewhere in Pennsylvania.

For his last two years of high school, Dick attended prep school at Marietta Academy on the Ohio side of the Ohio River. There he met and fell in love with Constance Henderson, a fellow West Virginian whom he later married in 1912 after he had established himself with the Reds and she had graduated from Hollins College. Dick starred at halfback for the 1905-06 Marietta College football teams and in the fall of 1907 enrolled at the Western University of Pennsylvania, which became known as the University of Pittsburg the following year. He played end for the famous WUP football team. Earlier that year Dick had played professional baseball with Clarksburg, West Virginia, of the Pennsylvania and West Virginia League, assuming the alias of “Hollister” to protect his amateur status. After playing shortstop for two weeks, the 6-footer was pressed into duty at the initial sack when Clarksburg’s regular first baseman got injured. Though Dick had never played the position before, it became the one that he manned for 1,284 contests in the majors.

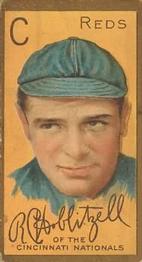

A note about Hoblitzell’s “handedness”: All of the standard reference works list him as a left-handed hitter and thrower, and I describe him as such in my biography that appears in Deadball Stars of the National League. In my research for this project, however, I interviewed Dick’s daughter, Connie (Hoblitzell) Michael, who commented on how strange it was that her father was a left-handed thrower when he did everything else (except bat) right-handed. My curiosity piqued, I checked out images of Hoblitzell on the Internet and am now convinced that the reference works are wrong, and that he was in fact a right-handed thrower. His T-206 tobacco card, for example, depicts him with a first baseman’s mitt on his left hand, but even more convincing are the four photographs from the Chicago Daily News collection on the Library of Congress’s web site, all taken during different seasons, showing him in the act of throwing right-handed. This also helps to explain Hobby’s start as a shortstop and the seven games he played at second base for Cincinnati in 1910.

When the 1908 school year ended, Dick jumped his contract with Clarksburg to join Reading, Pennsylvania, of the outlaw Union League. When that league folded after only six weeks, he accepted an offer from Newark of the Eastern League. Before Hobby appeared in any official games, however, the National Association informed Newark that its new first baseman still belonged to Clarksburg. Dick remained in Newark for two weeks, awaiting settlement of his case. On June 30 he was informed that Clarksburg had sold him to Wheeling of the Central League. Returning to his native state, Hoblitzell appeared in 53 games and attracted attention by batting .357.

On August 4, 1908, the Home Furniture Co., which owned the Clarksburg team, wrote the following letter to Frank Bancroft, business manager of the Cincinnati Reds: “We understand that your people are looking over young Hoblitzel [sic] now with Wheeling, Central League. This man belongs to us and we have had three offers for him, but have been trying to get more money for him. He is a very promising player with good habits and enough brains to do as he is told. If you want this man we will sell him to you for $1000, we can get this from other parties but would rather do business with you as our dealings with you in the past have been very satisfactory.”

The Reds purchased Hoblitzell from Clarksburg on August 21. In the interim between the letter and his purchase, however, St. Louis Cardinals manager John McCloskey had made a special trip to watch Hoblitzell play and had taken the young first baseman with him to St. Louis. When word reached Cincinnati, the National Commission (through Cincinnati owner Garry Herrmann, no doubt) immediately notified the Cardinals that Hoblitzell couldn’t play until title to him was resolved. Not surprisingly, the Commission ruled in Cincinnati’s favor, finding that Clarksburg had allowed Hoblitzell to play for Wheeling on condition that it retained the right to sell him to another club.

Making his debut with the Reds on September 5, 1908, Dick took over at first base for player-manager John Ganzel and batted .254 over the last 32 games of the season. In 1909 he appeared in 142 games and batted a career-best .308, third highest in the National League behind only Honus Wagner and teammate Mike Mitchell. When the 1909 season was complete, having shaved a year off his true age, Hoblitzell was considered a 19-year-old phenom whose “rise in baseball has been of the meteoric variety.” Commentators mentioned him in the same breath as Ed Konetchy and Kitty Bransfield as one of the NL’s greatest first basemen. Over the five-year period 1909-13, the left-handed-hitting slugger batted in the heart of the Cincinnati order and was the top run producer in the Reds’ strong offensive attack. During the offseason, Dick continued his education at the Ohio College of Dental Surgery and shared an office with his older brother, Bill, who had established a dental practice in Cincinnati.

During the first half of 1914, the 25-year-old Hoblitzell mysteriously lost his ability to hit, slumping all the way to .210 after 78 games. He cleared waivers, a trade with the New York Yankees fell through, and on July 16 the Boston Red Sox claimed him off the waiver wire for a mere $1,500. Hobby rebounded during the second half of 1914 to hit .319 in 69 games, plugging a hole in the Boston lineup and turning the Sox into pennant contenders. Assigned to share a room on the road with Babe Ruth (Connie remembers that her father would never tell Ruth stories in her presence), the steady and gentlemanly Hoblitzell remained Boston’s regular first baseman throughout the start of the 1918 season, usually batting third or cleanup in the batting order and performing well. In successive years, he hit .283, .259, and .257 in 1915 through 1917. He also performed admirably in the World Series of 1915 and 1916, playing in every game. He hit .313 in 1915 while six walks boosted his on-base percentage to .435 in the 1916 Series.

Declared eligible for the military draft, Dick took and passed an examination for the U.S. Army Dental Corps in March 1918. After reporting late to spring training, he opened the regular season with only one hit in his first 25 at-bats and was eventually benched with an injured finger on May 6. His replacement at first base that day was none other than his old roommate Ruth, making his first major league appearance at a position other than pitcher. Hoblitzell received his commission as a first lieutenant on June 6 and left the Red Sox three days later, his teammates presenting him with a gold wristwatch as a going-away present. Stuffy McInnis moved over from third base to fill the vacancy at first, Harry Hooper took over the captaincy, and the Red Sox went on to win another World Series, awarding Hobby a partial share of $300 from the proceeds. Dick never played another game in the majors, retiring with a lifetime batting average of .278.

While stationed in El Paso, Texas, Dick contracted influenza and nearly died during the 1918 pandemic. When he recovered, he was assigned to join his old Reds teammate Hans Lobert as a baseball coach at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, where Douglas MacArthur was serving as superintendent. After his discharge from the Army in 1920, Hoblitzell played for and managed the Charlotte Hornets of the Sally League for five seasons, leading the team to a pennant in 1923, and his daughter still uses a silver tea service he received from the Charlotte fans on “Hobby Day” in 1922. Around the time that Constance first became pregnant — the Hoblitzells eventually had two children that they named after themselves: Richard was born in 1925 and Constance was born in 1929 — Dick gave up baseball to work full time in the real estate business with his partner, Lee Kinney, though he eventually returned to the Hornets dugout in 1929-30 for the highest salary ever paid to that point to a Sally League manager.

Living in one of their own apartment buildings on Lamar Street, the Hoblitzells loved Charlotte and intended to make it their permanent home, but at the height of the Great Depression they were forced to return — temporarily, they thought — to Constance’s hometown of Williamstown, West Virginia, just across the Ohio River from Marietta, Ohio, where the couple had met, to save her family’s 540-acre farm. The Hendersons were among that area’s earliest settlers, tracing their roots to an ancestor from Alexandria, Virginia, who served in the Virginia House of Burgesses and who bought the property on the recommendation of its original surveyor, George Washington. But Constance’s father had died in 1926 and her mother couldn’t manage the farm on her own. Dick and his family moved into the 13-room farmhouse, which was built in 1875 on a hill overlooking the B&O Railroad and the Ohio River, and they never did make it back to North Carolina. Dick’s daughter, Connie, still lives on the farm in Williamstown to this day, though the property has been reduced to about 125 acres.

During the Depression many unemployed — the children called them “hoboes” — hitched rides on the railroad, looking for jobs, and Dick put them to work on the farm in exchange for a home-cooked meal and a place to sleep. There was an abundance of quail on the property, and Dick was an exceptional marksman. On one occasion he accumulated so many birds that he invited his fellow members of the Sons of the American Revolution to a quail dinner. The Hoblitzells expected eight to 10 guests, but every member in the valley showed up, filling the yard with cars, so Constance cut up what was intended to be a bird each into small pieces and somehow made do.

In addition to raising cattle and growing produce, Dick hosted a sports radio show on WPAR, wrote a column on sports and other topics for the Parkersburg News, and umpired youth baseball. He was active in Republican politics, serving as county treasurer and being elected sheriff. Dick also served as superintendent of the Sunday school at the Episcopal church. He never “officially” practiced dentistry, but he did set up a dental chair in his home and filled many a cavity for his neighbors, no charge, though without Novocaine. “It was not a pleasant experience having those big ol’ baseball hands stuck in your mouth,” recalls Connie. The former ballplayer kept himself in excellent shape, his weight never much exceeding his playing weight of 172 pounds, and he managed to avoid illness until he contracted the colon cancer that killed him on November 14, 1962.

Sources

The author wishes to thank Connie (Hoblitzell) Michael for her extensive help with this biography, and Bill Nowlin for putting him in touch with Connie. The other major source was Dick Hoblitzell’s clippings file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame. An earlier and much shorter version of this biography appears in the SABR book Deadball Stars of the National League.

Full Name

Richard Carleton Hoblitzell

Born

October 26, 1888 at Waverly, WV (USA)

Died

November 14, 1962 at Parkersburg, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.