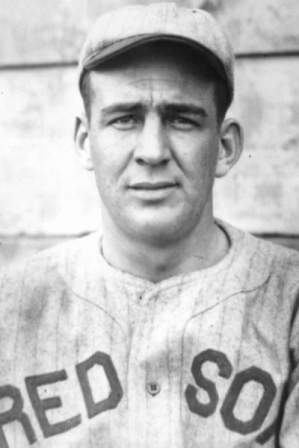

Roy Carlyle

Brothers Roy and Cleo Carlyle grew up in Norcross and Fairburn, Georgia, where their father, Will, ran a grocery store that had the only icebox in the area. When they weren’t working in the family store, the Carlyle brothers were out playing ball.

Brothers Roy and Cleo Carlyle grew up in Norcross and Fairburn, Georgia, where their father, Will, ran a grocery store that had the only icebox in the area. When they weren’t working in the family store, the Carlyle brothers were out playing ball.

Will and Rhoda (Bennett) Carlyle had three sons who played professionally. Roy and Cleo reached the majors; Eldon played briefly with the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association. Fairburn and neighboring Norcross were a small communities – Norcross was about 800 people at the time, but it produced four major-league ballplayers, all around the same time—the two Carlyles and the Wingo brothers, Ab and Ivey. Another Norcross alum, from an earlier time, was pitcher Nap Rucker.

Roy’s widow listed his descent as “Indian and Irish” on the player questionnaire she completed for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Curiously, his younger brother Cleo assertively wrote “American – English and Irish descent.” Roy was about 21 months older than Cleo, born on December 10, 1900 – though it’s not clear where. Baseball databases say he was born in Norcross, but one of the two questionnaires returned to the Hall of Fame reports that he was born in Buford, Georgia, while the other says he was born in Union City. And his State of Georgia death certificate says he was born in Fairburn. A Tampa Tribune story during his first spring training with a major-league ballclub cited Buford.1

Roy was the bigger of the two boys, growing to 6-foot-3 with a playing weight of 195 pounds. Cleo was three inches shorter and 25 pounds lighter. Both hit left-handed but threw right-handed.

Both boys attended elementary school in Fairburn and high school in Fairburn and Norcross, and Oglethorpe University for two years, where Roy was captain of the baseball team in 1921. Roy served in the United States Marines during the First World War, spending three months stationed in Boston. Roy’s first work in professional baseball was in 1921, at age 20, playing for Griffin in the Class D Georgia State League. Available statistics show him appearing in 14 games and hitting six home runs, with a .448 batting average. A broken leg ended his season.2 He played semipro ball in the early part of 1922, because his leg had not fully healed. When Arthur Ritter of the Atlanta Crackers was sold to Little Rock on waivers, Carlyle was brought to Atlanta to play in his stead, but it’s unclear whether he was able to play.3

For most of 1922, it seems Roy worked as an agent selling fire insurance out of Atlanta. It was a good position and he was reluctant to give it up to play baseball, but his boss told him, “You’ll never be satisfied until you try it. Go ahead and see what you can do. If you don’t like it, you can have your job back.”4

By 1923, he was ready to go. Charlotte paid a reported $100 for his contract and Carlyle played for the pennant-winning Charlotte Hornets in the South Atlantic Association in 1923, hitting .337 at Class B with 15 homers in 110 games. In 1924, for pennant-winning Memphis in the Class-A Southern Association, Carlyle batted .368 with 12 homers in a full 157 games. He was the first player in organized ball to reach 100 hits in that season, and led his league in base hits with 233 and runs batted in with 122.” 5 During June 1924, the Washington Senators purchased his contract on the recommendation of scout Joe Engle, with Carlyle to be delivered after the season.6

Roy “Dizzy” Carlyle broke into major-league ball early in 1925 with the Washington Senators, appearing in just one game, on April 16, in which he had just one at-bat, fanned by the Yankees’ Waite Hoyt in a pinch-hitting appearance. He was soon traded, on April 29, to Boston with Paul Zahniser for first baseman/left fielder Joe Harris. Washington manager Bucky Harris (no relation to Joe) said at the time that the Senators had been offered $30,000 for Carlyle late in the 1924 season. He called Carlyle a “great natural hitter.”7

Placed in left field by manager Lee Fohl, Carlyle hurt his shoulder slamming into the left-field fence in St. Louis and was out almost two weeks at the end of May. His bases-loaded double in the bottom of the ninth won the second game of the Bunker Hill day doubleheader, beating the White Sox, 5-3. Unfortunately, Carlyle played for a last-place team that season. Sometimes today’s Red Sox fans forget how bad the team really was in the post-Ruth, pre-Yawkey era. The 1925 team won just 47 games and finished 49 ½ games out of first place. Had Roy stuck with the Senators (was that strikeout so unforgiveable?), he might have played in the World Series that year. The rest of the Washington team did.

For Boston in 1925, Carlyle hit .326 with seven home runs and 49 RBIs in 276 at-bats, second only to Ike Boone’s .330 for average. Phil Todt (11) and Boone (9) were the only Red Sox to hit more homers. His two best games for Boston came against the White Sox. In the second game of a doubleheader at Fenway Park on Bunker Hill Day (June 17), he drove in six of the seven Red Sox runs in a 7-6 win and in the first game of the July 21 doubleheader in Chicago, he hit for the cycle and drove in four runs in a 6-3 Red Sox victory.

In 1926, Carlyle had a good day against his old team, batting out two doubles, a triple, and a single and scoring three runs in an 8-6 Red Sox win on April 25. Overall, Carlyle hit .285 for Boston but was placed on waivers. The Yankees wanted a left-handed pinch hitter, so they refused to waive him. Ultimately, the Red Sox let him go to New York, on June 26. He served the Yankees well, finishing out the season hitting .323 for New York.

Though he had a cumulative career average of .312 and had driven in 76 runs in 174 big-league games, his major-league career ended after the 1926 season. The problem was that he was a little slow in the field, and error-prone. With the Red Sox he’d had a fielding percentage of .874 in left field in 1925, committing 13 errors. His career fielding percentage was just .910 – nearly one of every ten balls he fielded was misplayed. When Boston put him on waivers, the Boston Herald wrote, “He is a powerful batter and a long hitter, but his fielding was so weak that Lee Fohl decided not to keep him on the payroll any longer.”8

Remarks were made about Roy endangering his life playing right field in Fenway Park. When Cleo Carlyle joined the Red Sox in 1927 and made some impressive fielding plays, Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald remarked, “More and more every day the wonder grows that Roy Carlyle can have such a clever outfielder in the immediate family.”9

On January 22, 1927, the Yankees released Roy to the Newark club (International League). He hit very well for Newark in 1927 but struggled early in 1928 and was transferred in midseason to the Birmingham team (Southern Association) where he had greater success at a lower-classification level.

As older brother Roy’s major-league days came to a close, younger brother Cleo (Cleo was his middle name, which he preferred to his given first name, Hiram) played outfield for the Red Sox in his 1927 rookie season. But Cleo played in the majors just this one year, hitting a very mortal .234, and driving in 28 runs, in 95 games

The Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League bought Roy’s contract in December, three days before Christmas. They got a good hitter for their money. In 1929, he played in 166 games, batting .348 with 22 homers and 108 RBIs – and just edging out Cleo, who was with the Hollywood Stars, by one point. Cleo hit .347, but did drive in 136.

Roy Carlyle kept playing ball for a few years after he left the majors, and is said to have hit baseball’s longest tape-measured home run (618 feet). In the second game of a doubleheader on July 4, 1929, Carlyle hit a tremendous drive off Ernie Nevers (taking a hiatus from his Hall of Fame football career), clear out of the Oakland Oaks’ old ballpark in Emeryville. The ball went over the clubhouse in center field, over the parking lot, and two buildings before it crashed into the gutter of a house, leaving a big mark on the metal. One of his teammates saw the impact, and was thus able to measure the distance. A week later in Salt Lake City, he hit a drive reportedly measured at 605 feet. The initial national news service story reporting the July 4 homer put the distance at 618 yards, which occasioned a few comments.10

His contract was sold yet again in December, to Kansas City. Press reports noted that he was “a hard hitter but is not considered much of a roamer in the gardens.”11 In January 1930, he married Myrtle Morris. He only played in ten games for K.C. before being sold in early May back to Atlanta. With the Crackers he hit .332 and improved his fielding to a .964 percentage.

It was a full 1931 season with Atlanta (.357, with 19 home runs), but fielding was a problem again (.939). After hitting .322 for Atlanta in the first month of the 1932 season, he was put on waivers and played the remainder of the campaign with both Scranton (of the New York-Pennsylvania League) and Indianapolis (of the American Association).

Myrtle Carlyle said Roy’s career ended in 1932. Despite her recollections, he played in five games for Charlotte in 1934. After leaving baseball, he was an owner of a hardware store in Norcross.

Roy Carlyle died of lung cancer on November 22, 1956. He had been ill for about a year before his death.12

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Carlyle’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson, Dixie Tourangeau, and also to Will Hammock of the Gwinnett Daily Post for some of the information contained in this biography.

Notes

1 Tampa Tribune, March 7, 1925.

2 Ibid.

3 New Orleans Item, July 11, 1922, and the Tampa Tribune, March 7, 1925.

4 Boston Globe, July 6, 1925.

5 The June 25 Washington Post noted his reaching the century mark, with his 100th hit the day before.

6 The story of the deal with Washington was reported widely. See, for instance the Charlotte Observer of June 15, 1924. Joe Engle as scout was mentioned in the 1925 Tampa article, though his name was misspelled.

7 Boston Herald, April 30, 1925.

8 Boston Herald, June 16, 1926.

9 Boston Herald, March 14, 1927.

10 See for instance the Augusta Chronicle of July 24.

11 San Diego Evening Tribune, December 7, 1929. He had a .946 fielding percentage with Oakland, so he was improving on defense.

12 The Sporting News, December 5, 1956.

Full Name

Roy Edward Carlyle

Born

December 10, 1900 at Buford, GA (USA)

Died

November 22, 1956 at Norcross, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.