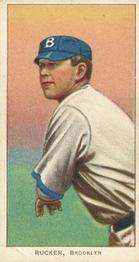

Nap Rucker

Nap Rucker was one of the Deadball Era’s top left-handed pitchers. Brooklyn’s winning percentage was an even .500 when the hard-throwing Southerner got the decision, but without him the Superbas played .430 ball, losing 175 more games than they won. “The Rucker appendage is the only thing that has kept Brooklyn in the league,” wrote the New York Herald, while the Brooklyn Eagle lamented that “the fates have tied him up with an aggregation that has steadfastly refused to make a bid for championship honors.” Still, the gentlemanly Rucker loved pitching for the blue-collar borough. “It’s got New York beaten by three bases,” he told a reporter in 1912. “You can get a good night’s rest in Brooklyn. You meet more real human beings in Brooklyn. Your life is safer in Brooklyn.”

Nap Rucker was one of the Deadball Era’s top left-handed pitchers. Brooklyn’s winning percentage was an even .500 when the hard-throwing Southerner got the decision, but without him the Superbas played .430 ball, losing 175 more games than they won. “The Rucker appendage is the only thing that has kept Brooklyn in the league,” wrote the New York Herald, while the Brooklyn Eagle lamented that “the fates have tied him up with an aggregation that has steadfastly refused to make a bid for championship honors.” Still, the gentlemanly Rucker loved pitching for the blue-collar borough. “It’s got New York beaten by three bases,” he told a reporter in 1912. “You can get a good night’s rest in Brooklyn. You meet more real human beings in Brooklyn. Your life is safer in Brooklyn.”

The son of a former Confederate soldier, George Napoleon Rucker was born on September 30, 1884, in Crabapple, Georgia, just north of Atlanta. As a red-headed youth he worked as a printer’s apprentice, and one day he was given a headline to set in type: “$10,000 FOR PITCHING A BASEBALL.” That moment, Rucker always claimed, was when he decided to become a pitcher. He joined a local semipro team and caught the eye of the Southern League’s Atlanta Crackers, who signed him on a trial basis. Years later, Bill Nye, the famous bodyguard to presidents Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson, claimed he was the scout who recommended Rucker to Atlanta. Nap pitched his first professional game on September 2, 1904, but was farmed out to Augusta at season’s end.

Rucker’s teammates on the 1905 Augusta team included Eddie Cicotte, Clyde Engle, and a 19-year-old Ty Cobb. The two Georgians roomed together and often went to the park early so Cobb could practice hitting against left-handed pitching. That season Nap became one of the first players to experience his roommate’s fury firsthand. When they arrived home after each game, Cobb would bathe first, then Rucker, but one day Nap was knocked out of the game and left the park early. Cobb arrived home to find Nap already in the bathtub and flew into a rage, attempting to choke the naked Rucker. “You don’t understand,” Cobb seethed, “I’ve just got to be first—all the time.” After compiling a 13-11 record in 1905, Rucker returned to Augusta the next year and got off to a spectacular start, prompting rumors that the Philadelphia Athletics were about to purchase him. The deal fell through, however, and Nap finished the 1906 season in the Sally League, ending up at 27-9.

That off-season the Brooklyn Superbas drafted Rucker for $500. The 22-year-old rookie quickly established himself as the staff’s ace, more than earning his $1,900 salary by going 15-13 and leading the team in innings (275), strikeouts (131), and ERA (2.06). Rucker was even better in his sophomore season, somehow winning 17 games for a team that lost 101. The highlight came at Washington Park on September 5, 1908, when he pitched a no-hitter, striking out 14 Boston Doves. Three years later Nap flirted with a second no-hitter, pitching 8⅔ hitless innings against Cincinnati on July 22, 1911, before Bob Bescher bounced a chopper up the middle for a single.

In 1909 Rucker set a career-high with 201 strikeouts, and on July 24 of that season he struck out 16 St. Louis Cardinals, tying the modern record that stood until Dizzy Dean broke it in 1933. (Nap always claimed that he fanned 17 that day, but a lackadaisical official scorer whose name he still remembered—Abe Yager—forgot to record one of them.) Once again he was the best pitcher on a terrible team, going 13-19 despite a 2.24 ERA. His record improved to 17-18 in 1910, the year he led the NL with 320 innings pitched, 27 complete games, and six shutouts. Rucker started 1911 with six consecutive losses—during which Brooklyn scored a total of 10 runs—but rebounded to post the only 20-win season of his career, finishing at 22-18. In 1912, however, he reached the 20-loss plateau, going 18-21 despite a 2.21 ERA, more than a full run better than the league average.

All the strikeouts, no-hit bids, and low ERAs brought Rucker acclaim as one of the NL’s fastest pitchers. On October 6, 1912, he and Walter Johnson became the first to have their throwing speed scientifically measured when they submitted to testing at the Remington Arms Plant in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Using copper wires set up several feet apart, the rudimentary test measured the amount of time it took the pitches to travel a given distance. It almost certainly underestimated the pitcher’s speed: Rucker tested at 113 feet per second (77 mph), Johnson at 122 (83 mph). When not subjecting himself to speed-throwing experiments, the Brooklyn lefthander spent his off-seasons as a typesetter for the Marietta Free Press, a newspaper owned by a cousin. To his managers’ dismay, he also spent much of his winters eating peanuts and ice cream. Never one for vigorous training, Rucker routinely reported to camp weighing 210 lbs., though by Opening Day he was usually down to his playing weight of 180.

By 1913 Rucker’s fastball had begun to fade, and he started throwing a strange, particularly effective slow curve—called “the slowest ball in the history of the majors” by one reporter. Nap claimed he learned the pitch with Augusta when he accidentally gripped the ball the wrong way, but another story attributes its origin to a 1913 thumb injury that forced him to change his grip. Others, meanwhile, claimed that the pitch was an early version of the knuckleball. Whatever it was, reporter Dan Daniel called it “one of the amazing phenomena of baseball history.” Rucker relied on it to put together one last workhorse season, pitching 260 innings and ending up at 14-15, after which he was named baseball’s best left-handed pitcher in a poll of sportswriters.

In 1914, however, Rucker had developed a sore arm, and for his last three seasons he pitched effectively only with two weeks rest. The veteran southpaw then became a mentor to many of Brooklyn’s younger players. “When I broke in I couldn’t hit a low ball,” recalled Casey Stengel. “Nap took me to the park every morning and fed me low balls. If it hadn’t been for him I reckon I wouldn’t have even stayed in baseball.” But still there was one thing that had eluded Nap during the course of an otherwise successful career. “I would give a great deal of money to have my club in a World’s Series,” Charles Ebbets told Damon Runyon in 1915, “if only for the honor it would bring Rucker. I will always regard him as one of the greatest men the game has produced—greatest in every way.”

On August 1, 1916, Rucker pitched 5⅔ innings of scoreless relief against Cincinnati to earn the 134th and final victory of his major league career. The win evened his lifetime record at 134-134, with 28 percent of those victories coming by shutout (the second-highest percentage in history, behind only Ed Walsh). His career 2.42 ERA was 85 percent of the league average, which was 2.85 over the same period. To honor its best pitcher of the Deadball Era, Brooklyn held a “Nap Rucker Day” at Ebbets Field on October 2, 1916. “I will not monkey around with baseball any more,” the veteran southpaw said on the occasion. “I have had my day, and it has been a long one, in which I have made money and gained thousands of friends.” Knowing that Rucker would retire after the season, Wilbert Robinson allowed him two innings of mop-up duty in Game Four of the 1916 World’s Series. Rucker pitched scoreless ball, striking out three Red Sox in his swansong.

In retirement Nap Rucker returned to Great Oaks, his mansion in Roswell, Georgia. There he owned the local wheat mill, became an investor in the town bank, presided over two small cotton plantations, and umpired occasionally in sandlot baseball games. He also scouted the South for the Dodgers, finding such players as Dazzy Vance, Al Lopez, and Hugh Casey. Feeling the pinch of the Great Depression, Brooklyn declined to renew his contract in 1934, at which time he ran unopposed for mayor. Rucker was a segregationist Democrat; as one writer put it, “he could not be anything else politically and still be a Georgian.” As mayor during the New Deal, the former pitcher was instrumental in bringing running water to Roswell and later served as the town’s water commissioner for several decades.

In 1939 the Dodgers re-hired Nap as a scout, and the following year his nephew Johnny Rucker made his major league debut with the New York Giants. After a brief stint working for the US Government in Panama during World War II, Nap Rucker and his wife, Edith, whom he had married during the 1911 season, returned to Georgia. There they lived in semi-retirement until Nap died at age 86 on December 19, 1970.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

George Rucker

Born

September 30, 1884 at Crabapple, GA (USA)

Died

December 19, 1970 at Alpharetta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.