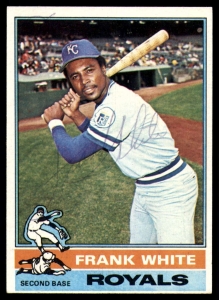

Frank White

It’s easy to find high praise about Frank White from members of the Baseball Hall of Fame, ranging from managers and executives for whom he worked (John Schuerholz and Whitey Herzog) to longtime players on opposing teams such as Reggie Jackson.1 Still, there may be no more significant comment about White than from Hall of Famer George Brett. During spring training in 1991, Brett was openly emotional about losing teammates. “This game’s a business and I understand that,” Brett said. “But it really strikes you hard when [it’s] someone close to you, someone that you have a lot of respect for, not only as a player but as an individual.”

It’s easy to find high praise about Frank White from members of the Baseball Hall of Fame, ranging from managers and executives for whom he worked (John Schuerholz and Whitey Herzog) to longtime players on opposing teams such as Reggie Jackson.1 Still, there may be no more significant comment about White than from Hall of Famer George Brett. During spring training in 1991, Brett was openly emotional about losing teammates. “This game’s a business and I understand that,” Brett said. “But it really strikes you hard when [it’s] someone close to you, someone that you have a lot of respect for, not only as a player but as an individual.”

“Frank White and I were teammates for 20 straight years,” Brett continued. “We started off in 1971 together in the instructional leagues and played every year together from 1971 up until this spring.” Brett hadn’t felt White’s absence through mid-March because the few familiar faces in spring-training camps get lost among the long shots who flood the lineups. “But come Opening Day, when I’m out there and Frank’s not there, then it’s going to hit me: Frank’s no longer on our team.”2

At that point, Frank White had lived half of his life in the Royals organization. How he got into it in the first place was rare and remarkable.

Frank White Jr. was born on September 4, 1950, in Greenville, Mississippi to Frank White Sr. and Daisie Vestula (Mitchell) White.3 Daisy’s parents, Roosevelt and Bertha Mitchell, were sharecroppers about 20 miles to the north near Grapeland, Mississippi. Frank Jr. reported vivid memories of picking cotton there during several summers.4

Frank White Sr. was also born in Greenville. He served in the military during World War II in Germany. He played amateur baseball as a young adult, and may have had professional aspirations. “The Negro Leagues were just winding down and I think he had a shot at going down and playing with the Memphis Red Sox,” Frank Jr. wrote in his 2012 autobiography.5 It so happened that in early 1950, Red Sox manager Homer “Goose” Curry ran a baseball school for African-American players in Memphis. The school’s assistant director was Boyce Jennings, manager of the Greenville Delta Giants of the Negro Southern League. The school opened in late February.6 Only a few of the 40-plus participants were ever named in local newspaper accounts, but three were from Greenville,7 and one history of the NSL lists “Frank White, 3b” on the roster of the Greenville Delta Giants in 1950.8 Also, before the start of the NSL season, the Delta Giants faced another team in the league, the New Orleans Creoles, and a preview of the game reported that Jennings planned to have Frank White among his infielders. The Greenville daily made a big deal about the fact that female player Toni Stone was with the Creoles, but the day after the game it printed only one paragraph about the contest and didn’t name any of the players.9

Though born in Greenville, Frank White Jr. said he lived in Benoit, about two miles north of Grapeland, until his parents moved the family to Kansas City when he was 6 years old. Despite his old and new homes being about 600 miles apart, Frank Jr. said his parents continued to send him and three siblings to their grandparents every summer; “our folks thought maybe if they sent us back there it would keep us out of trouble.”10

It was a tradeoff, due to the racial tensions of the 1950s and 1960s. “It was tough being black anywhere in the United States back then,” White said, “but it was really tough in Mississippi.”11 His mother’s sister Louella was the first relative to try moving to Kansas City for a better job and a higher standard of living. Daisie White spent her entire working life there pressing clothes in the city’s Historic Garment District. Her husband worked for various car dealers.12

Their son Frank’s first school in Kansas City was Wendell Phillips Elementary. For fourth grade he started being bused Linwood Elementary.13 It was around that time, at the age of 9, that he first played baseball in an organized league. Frank started learning the game simply by playing with neighborhood kids, without adult coaching. His first glove was a first baseman’s mitt because that was his main position early on. When he started playing organized ball his father never missed a game, but anger management was an issue at times, and he was asked to leave some of his son’s games. “When I was playing a position he was fine,” Frank White Jr. recalled, “but when I pitched he didn’t always see eye to eye with the umpire, so he watched a few games from the car.”14

After Linwood Elementary, White attended Lincoln High School, a historically significant institution founded for African-American students in the 1800s and the only high school in the region they could attend until at least 1950. It was integrated about a decade after White graduated.15 Lincoln is a block from the site of Municipal Stadium, home of the Royals for their first four seasons as well as the A’s while the franchise was located in Kansas City. Lincoln didn’t have a baseball team but White played football and basketball. It was through Connie Mack, Ban Johnson, and Casey Stengel leagues that he honed his baseball skills into his teens.16 He was on a Hallmark Card team made up of 14-year-olds that won a Connie Mack League championship, and at the age of 18 he was on a Safeway grocery store team led by Hall of Famer Hilton Smith. White represented the latter team in a Casey Stengel League All-Star Game played in Municipal Stadium.17

The assassination of the Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, happened shortly before White graduated from Lincoln. The worst rioting occurred only two blocks from the family’s home. In the midst of that, Frank White Sr. managed to drive his pregnant daughter Mona to a hospital because she’d just gone into labor.18

Frank White’s first job after high school was as a stock handler for Hallmark Cards, for which he made $100 a week. He later worked for the Metals Protection Plating company. He also briefly attended Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.19

On September 11, 1969, the course of Frank White’s life shifted dramatically. During the Royals’ first season, owner Ewing Kauffman announced a detailed plan to open a “baseball academy” in Florida in 1970 for about 50 recruits primarily 17 and 18 years old. Syd Thrift, Kaufmann’s director of scouting for the Eastern half of the United States, was named director. “This is the only way Kansas City can have a winning team right away,” Kaufmann said.20

“I always wanted to play baseball, but I never thought I could play and get paid for it,” White said. “I dreamed about it, but you dream about a lot of things that never happen.” He heard a little about tryouts for the academy, but doubted he could get off work to attend. But Hilton Smith and White’s high-school science teacher and basketball coach, Bill Rowan, urged him to make the effort. He also received encouragement from scout Bob Thurman and brothers Don and Bob Motley, significant figures in Negro Leagues history.21

White went to Municipal Stadium on the first day of a two-day tryout, and found about 300 other young men with similar dreams. After sprints and fielding exercises on the field, some of the applicants were sent to a doctor inside the building for coordination tests. When White was later in the batting cage, he overheard former A’s first baseman Norm Siebern say, “You need to take a chance on this kid.” White didn’t know who the other man was, but when the two talked about White’s age, Siebern said it was only important that White was obviously an athlete. Moments later, though, White was crushed when he also overheard that the plan was to send only unmarried players to the academy. White was married, and he and his wife, Gladys, had a baby, Frank III. When his tryout concluded, he thought his baseball playing days were over.22

“Then, something that only happens in movies happened to me,” White’s 2012 autobiography says. “Later that day, I was at my parents’ house and I hear this commotion outside. I look out the window and there is a big blue limo parked in front of our house.” It was Kauffman’s, but the owner wasn’t in it. He didn’t send it to take White somewhere; he only wanted to speak with White on the limousine’s car phone (decades before there were such things as cell phones). “I’d never talked on a phone in a car before — I didn’t even know there was anything like that — and we started our conversation,” the book says. Kauffman said another married player, catcher Art Sanchez, agreed to attend the academy, and Kauffman would give Frank’s wife, Gladys, a job in the camp’s ticket office if that would enable White to enroll. White replied that he’d need to discuss the offer with his wife and parents first, and soon agreed.23

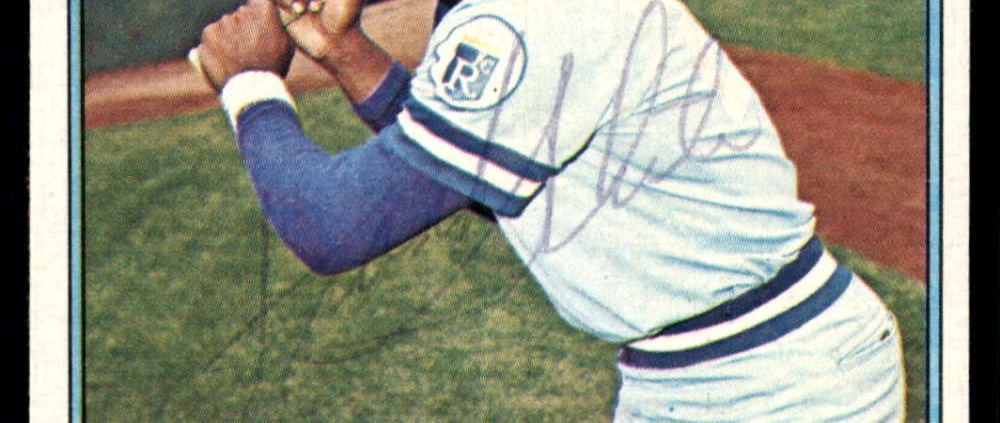

Thrift, Kauffman, and his wife held a press conference at Municipal Stadium to name the academy’s first 15 students, and seven were present. White can be seen in a photo from that announcement, standing near the Kaufmanns. The Royals listed him as 5-feet-11, 167 pounds, and an outfielder.24 About two months later, an academy team played its first game, against the semipro Sarasota Grays. White started the scoring in the first inning with a two-run homer, and his team won, 10-0.25

By the spring of 1971 White was officially a professional ballplayer, with the Royals’ team in the rookie-level Gulf Coast League. Before that, players who had completed the academy’s first year made a 16-day tour of Central and South America. White was one of eight players on that tour who hadn’t played an inning of baseball in their high schools.26 By the start of the 1972 season the academy had put 14 players into the Royals’ minor-league system, and White had already played some exhibition games for Triple-A Omaha and Double-A Jacksonville before being assigned to San Jose in the Class-A California League.27 He was told that Omaha manager Jack McKeon wanted to keep him, but White ended up splitting the 1972 season between San Jose and Jacksonville. He found the city of San Jose to be “exciting” but he was very uncomfortable when he returned to Florida. The academy at Sarasota was a self-contained community, but with Jacksonville his team traveled much more, and he quickly grew uncomfortable seeing signs supporting the Ku Klux Klan. He was the only African-American player with Jacksonville at the time, so at various stops his teammates got in the habit of bringing food and drinks to him while he remained on the bus.28

White started the 1973 season with Omaha. He was batting .280 when in early June it was announced that an injury would keep Royals shortstop Freddie Patek inactive for at least 10 days, and suddenly White found himself in the majors.29

White heard much later that there was resistance within the Royals’ front office to calling him up, but that Jack McKeon, who had advanced from Omaha to managing Kansas City, reportedly said, “Send me Frank, or don’t send me anyone.” White made his major-league debut on June 12, 1973, in Baltimore. He replaced Bobby Floyd at shortstop in the bottom of the sixth inning. “The first ball that was hit to me was a high chopper that I lost in the lights and it hit me in the chest,” White recalled. “I was thinking to myself, ‘I’m glad that didn’t happen in Kansas City.’”30

White grounded out to second in his only time up in the game, and went hitless in four at-bats as leadoff hitter the next night. His first two hits came against Doyle Alexander in his third game. In his sixth game he had three hits and a sacrifice fly in five plate appearances against Gaylord Perry. White led off the game with a triple, and his next time up Perry threw a pitch at White’s head. “He flipped me good,” White recalled. “I didn’t know about things like that. Gaylord thought I was showing him up, so he threw at my head.” This was presumably when White batted for the second time, in the top of the second inning. White singled off Perry and drove in a run. Then in the bottom of the frame, Royals pitcher Dick Drago struck out catcher Dave Duncan and then hit Chris Chambliss on the hand. “He did it for me,” White said. Drago “was protecting me and the rest of our hitters.”31

White played his first game as a pro in Kansas City on June 18, in a 9-5 loss to the Oakland Athletics. In his 2012 autobiography he admitted that he didn’t remember the game, in which he went hitless. He had two hits in five at-bats the next game. He did retain vivid memories of having been a construction worker at Royals (now Kauffman) Stadium, which had opened weeks earlier. Ewing Kauffman had arranged for White to work there during the previous offseason.32

On June 28, numerous newspapers printed an Associated Press story that profiled White as the academy’s first graduate to reach the major leagues. In it he credited Gladys for encouraging him to try out for the academy and acknowledged Siebern’s crucial praise. “I have no intention of sending White back to Omaha with Patek coming off the disabled list,” McKeon emphasized. “I think White can help us. He can play shortstop, and he can play second base. He has proven that.”33

A few weeks later the Royals acquired pitcher Joe Hoerner, and on July 20 White was returned to Omaha. In 27 games he batted .236.34 He played 86 games for Omaha in 1973 and batted .264; he never played another game in the minors. He was one of the players called up from the minors when rosters expanded on September 1, and the Kansas City Times, writing about the September 18 “Farm Pheenoms Night,” highlighted White’s 2-for-4 performance at bat along with George Brett’s fielding. White and Brett batted first and second in the lineup.35 White ended 1973 with 51 games for Kansas City and a .223 batting average. He then played winter ball in Venezuela under teammate Cookie Rojas, whose starting job at second base White ended up taking in 1976. White described in detail in his autobiography the help Rojas provided.36

On April 6, 1974, the Royals’ second game of the season, White hit his first major-league home run. They hosted Minnesota and pounded six Twins pitchers, 23-6. White led off the seventh inning with a blast off Tom Burgmeier.37 That season he started 25 games at second base, 17 at shortstop, and 10 at third base. In 1975 he started 57 times at second, 26 at short, and 2 at third base. In 1975 only Sandy Alomar and Pedro Garcia had better fielding percentages among second basemen who played in more games than White, and then only by a single percentage point, at .985.38

In 1976 White became the Royals’ second baseman full time and also had his first postseason experience. Though Cookie Rojas had no longer been the team’s starting second baseman, he and White split that duty in the American League Championship Series against the Yankees, who won the series three games to two. White didn’t play in the final contest but still called it “one of the most heartbreaking games” of his entire life when Chris Chambliss homered to break a 6-6 tie in the bottom of the ninth inning.39

The ALCS outcome was the same in 1977, between the same two teams, and White found that the fifth game was even more gut-wrenching than a year earlier.40 At least in the 1977 ALCS White was able to play full time, and showed up well with a .278 batting average. For that season he was awarded the first of six consecutive Gold Glove Awards. (He earned his seventh and eighth Gold Gloves in 1986 and 1987.) White said a last big leap forward as a student of fielding occurred when he played ball in Puerto Rico after the 1976 season.41

In mid-1978 White was named a reserve on the AL All-Star Team. He was also an All-Star in 1979, 1981, 1982, and 1986. In the 1978 All-Star Game he batted once and he popped out afainst Rollie Fingers. Decades later White didn’t recall much about the experience, except that “it was so much fun being around the stars of the game.” He noted that players “didn’t fraternize much back then, but at the All-Star Game you could talk to the guys you played against and you could talk to the National League players you never saw.”42

In 1978 the Royals faced the Yankees in their third consecutive ALCS, losing in four games. In hindsight, White suspected that he actively tried to forget that rematch.43 The Royals didn’t win their division in 1979, but White was selected by fans as the AL’s starting second baseman in the All-Star Game. That season he achieved one personal best of note: His 28 stolen bases that season were the highest total of his career. He first reached 20 steals in 1976, and then had 23 in 1977. His best success rate was in the latter season, when he was caught only five times.

The Royals achieved a major milestone in 1980 by sweeping the Yankees in the ALCS. White was named the MVP of the series with a .545 batting average. He and the Royals played in their first World Series, against the Philadelphia Phillies.

Toward the end of the World Series, the Jackson (Mississippi) Clarion-Ledger’s Steve Doyle called White “a refreshing change” in an era of “the aloof superstar,” and added, “He’s a scholar and a gentleman, quiet and unassuming, confident, yet, not cocky.” Doyle invoked two familiar names who were covering that World Series. “He is one beautiful person,” said NBC-TV sportscaster Tony Kubek. Doyle noted that at least twice Sparky Anderson, working the Series for CBS Radio, proclaimed White the best in all of baseball. White laughed off the latter claim, saying, “I heard Sparky, and he said Willie Randolph is the best.”44 The Phillies won the World Series in six games.

The Royals returned to the playoffs in 1981 and 1984 but both times they were swept in three games. In between, White had a particularly good year in 1982 with 45 doubles and a .298 batting average, both career highs, and in 1983 he was named Royals Player of the Year for the first of two times. He also led AL second basemen in putouts for both 1982 and 1983. In 1984, for the seven days starting August 5, he was named AL Player of the Week.45

Then came 1985. During the regular season he hit a career-high 22 home runs, and on defense he led all AL players, regardless of position, with 490 assists.46 The Royals won their division for the last time in his tenure, and beat the Toronto Blue Jays in the ALCS, four games to three. In preparation for the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, Royals manager Dick Howser summoned White into his office. “We can’t use the DH, and since you had those 22 home runs during the season and have hit fourth a few times, I’d like you to hit cleanup,” Howser said. “You gotta be kidding me,” White replied. Howser wasn’t joking.47

The Royals lost the first two games at home but in Game Three found themselves up 2-0 in the top of the fifth inning. George Brett led off with a single against St. Louis starter Joaquin Andujar, and then White knocked Andujar out of the game with a blast over the wall in the left-field power alley. Not surprisingly, White wrote at length about it:

“That was the longest home run I ever hit — and the most special. When I hit it, I watched (Tito) Landrum in left field and he never moved. When you’re not known for hitting home runs, and you get one like that you’re always going to remember it. I knew it was gone, so I wanted to make sure I ran the bases just right — not too fast and not too slow. I tried to be the ultimate professional and not show up the other team or the other pitcher. I still get chill bumps just thinking about it. I’d hit that home run a thousand times in the alley behind my house and in the park in our neighborhood, but now it really happened.”48

The Royals won the game, 6-1, but were shut out in Game Four, so each remaining game was do-or-die. In Game Five, White drove in the first run in another 6-1 victory, and that sent the Series back to Kansas City for one or two more games. The Royals eked out a 2-1 win in Game Six to knot the Series at three games each. Much attention has been focused on first-base umpire Don Denkinger’s botched “safe” call in the bottom of the ninth inning,49 but two decades later Jason Roe of the Kansas City Public Library noted that “many fans have forgotten another call — one that benefited the Cardinals. In the fourth inning of Game Six, the Royals’ Frank White appeared to have stolen second base, but was called out,” Roe wrote. “The next batter, Pat Sheridan, hit a single to right field that would have allowed White to score the go-ahead run for the Royals.”50 Instead, the Royals didn’t score until that memorable bottom of the ninth, which White called his “single greatest moment as a Royal. When we scored that run, we all knew we were going to win Game 7.”51

The Royals won the World Series the next night, with an 11-0 blowout. White had a batting average of .250 in the World Series with a Series-leading six RBIs, four runs scored, three doubles, that important Game Three homer, and three walks.52

In 1986 the Royals slid to third place in their division, and didn’t have a winning record, but that season may have been White’s best. He was an All-Star again, and his homer in the seventh inning provided the decisive run. White achieved lifetime bests with 84 RBIs and 76 runs scored, and tied his career high with 22 home runs. He was named Royals Player of the Year for the second time and received his only Silver Slugger Award.53 After the season he was among the players who traveled to Japan for a seven-game exhibition series.54

White’s All-Star Game home run was a big thrill at the time, but soon became bittersweet. The AL manager was his own, Dick Howser. “My first all-star hit was a homer — and it was for Dick. I was so happy running around the bases,” White wrote. “It looked like we were finally going to win my first All-Star Game and I was going to be able to share it with Dick and George [Brett]. Dick was so happy after we won.” White knew at the time that Howser was battling cancer, but added, “[W]e had no idea how bad it all was. But the smile on his face when we won that game 3-2 was something I will always remember.”55

In 1987 White became the first American League second baseman to be awarded an eighth Gold Glove.56 A final milestone came at home on September 11, 1990, when he doubled home two runs with his 2,000th hit. More than 18,000 fans gave him a prolonged standing ovation. White stepped off second base and responded to the warm cheering with a smile and tip of his cap. “I respect them so much, I had to give them a bow,” White said of the crowd. “They’ve been so good to me for so long.”57 He played his final major-league game at the end of that month, not by choice. The end of his career was awkward, to say the least.

A month after White’s last game as a Royals player, Gib Twyman of the Kansas City Star expressed frustration about the aftermath. “It would be nice to see the Kansas City Royals not drop the ball on the departure of another of their fixtures, Frank White,” he wrote. He observed that “the Royals have had a pretty tough time with these kinds of things over the years.” Twyman alluded to a certain irony for “a club that has prided itself on organization, family, togetherness.” How many of their great players, he wrote, “have wound up working here as scouts, coaches, instructors, front-office personnel? Some. Precious few, really.”

“White’s feelings are hurt, no matter what he says for print,” Twyman concluded, and implied that White didn’t make it easy on his team toward the end. “But White has meant too much to the team and town to just let him go away. Somehow, you’d like to see the club be creative enough that their longtime stars still seem part of them.”58

White’s relationship with the Royals swung from positive to negative and back over the years. In 1992 he jumped to the Boston organization, beginning with a season as manager of their Gulf Coast League rookie team. From 1994 to 1996 he was the first-base coach for the Red Sox. In the midst of that he was inducted into the Royals Hall of Fame in 1995 and his uniform number 20 was retired. He returned to the Royals in 1997, initially as the club’s community outreach representative, but during the 1997 season he took over as first-base coach and continued in that role through 2001.59

Around the time White left Boston’s organization, he and Gladys divorced after about 25 years of marriage. His first job after returning from Boston was with Blue Cross Blue Shield. There he met Teresa, who became his second wife on October 7, 2000.60 In 2002 he entered the Royals’ front office as special assistant to the general manager and in 2003 added manager of the Arizona Fall League’s Peoria team to his duties. In 2004 a statue of White was erected on the ballpark grounds.61 “That was one of the most special moments in my life because my father passed away a few months after that ceremony,” White wrote. “I am so proud and honored that he lived long enough to see my statue, because I know it made him proud of me.”62

From 2004 through 2006 White coached the Royals’ Wichita team in the Texas League, and then switched to community relations, among other things by engaging with MLB’s RBI (Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities) program.63 In 2007 White became a senior adviser to the Royals, and in 2008, he added a part-time role with Fox Sports Kansas City as part of the team televising Royals games. From 2009 through 2011 that role increased to almost full time as broadcaster and former teammate Paul Splittorff slowly succumbed to cancer. White resigned the senior adviser position early in 2011 and declined a community-relations position.64

White’s mother died in February 2010, so when his autobiography was published two years later, that personal loss was still very fresh in his memory, as was the erosion of his relationship with the Royals. “You’ll never see me in that stadium again,” White wrote in the book. However, his concluding words in it were, “Will I step back in that stadium? Never say never.”65

In 2012 White joined the Kansas City T-Bones in the independent American Association and he continued in that role through 2016.66 His relationship with the Royals started to revive in 2014,67 and on September 1, 2015, when the Royals held their “Franchise Four” event honoring George Brett, White, Bret Saberhagen, and the late Dan Quisenberry as the four best players in team history, White attended and appeared to enjoy himself.68

In 2014 White ran nd was elected to the Jackson County Legislature. On January 11, 2016, the county legislature appointed him county executive.69 As a result, he took part in the Royals meeting with President Barack Obama after they won the 2015 World Series.70

White received considerable negative publicity in 2018 as a result of thousands of dollars in unpaid taxes and related financial problems, which led him to sell some of his memorabilia.71 He had admitted in his autobiography that the players strike during the 1981 season caused financial hardship for him, and that being fired in late 2011 did likewise.72 The news didn’t seem to affect voters’ attitudes about him much. On August 7, 2018, he received 68 percent of the vote in the primary for county executive, and on November 6 he was re-elected easily.73

So what exactly did John Schuerholz, Whitey Herzog, and Reggie Jackson say about Frank White? “Frank White is the best second baseman I have ever seen play,” said Schuerholz. “He was like [dancer] Rudolf Nureyev at second base. Frank’s athletic ability, agility, and physical play was unparalleled to me. In addition, he’s a really classy guy.” Herzog’s assessment began similarly: “Frank White was the best defensive second baseman I have ever seen. I’ve seen second basemen that were pretty darn good such as Bobby Richardson and Bill Mazeroski. Frank played second base for me for five years and I just don’t see how you play the position defensively any better than he played it.”74 Reggie Jackson took his praise in a somewhat different direction: “Frank White saved as many runs as I drove in,” said Jackson. But leave it to George Brett to sound more like his bosses Schuerholz and Herzog: “ ‘It`s like that song by Carly Simon: ‘Nobody Does It Better.’”75

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 See Denny Matthews with Matt Fulks, Denny Matthews’s Tales from the Royals Dugout: A Collection of the Greatest Stories Ever Told (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, LLC, 2004), 106 and 107, for quotes by Schuerholz and Herzog. See Frank White with Bill Althaus, One Man’s Dream: My Town, My Team, My Time (Olathe, Kansas: Ascend Books, 2012), 2, for a quote by Jackson and a different but equally strong quote by Schuerholz.

2 Claire Smith, “Brett’s Fading Friends: It’s All in the Game,” New York Times, March 27, 1991: B11. Brett’s baseball-reference.com stats for 1971 are limited to Billings in the Pioneer League, but toward the end of that year he and White were in the Florida Instructional League together. For example, see “Red Sox Pitchers Blank FIL Pirates,” Sarasota (Florida) Herald-Tribune, October 16, 1971: 3-C. White and Brett were in opposing lineups and the latter homered as “the Kansas City Royals outslugged the Kansas City Baseball Academy 10-9 at the KC Complex.”

3 David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball, Q-Z (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000), 1660.

4 Frank White with Bill Althaus, One Man’s Dream: My Town, My Team, My Time (Olathe, Kansas: Ascend Books, 2012), 23.

5 White, 29, 30.

6 “Baseball School May Save Sports,” Plaindealer (Kansas City, Kansas), February 24, 1950: 4.

7 For example, see “Negro Baseball School to Meet Martin on Friday,” Delta Democrat-Times (Greenville, Mississippi), March 15, 1950: 8. Players from Greenville who were mentioned were brothers Joe and Tom Barnes, both right-handed pitchers, and slugger Sid Wright.

8 William J. Plott, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920—1951 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2015), 237. Greenville was also home to a “Colored” semipro team, the Brown Bombers, in 1948 and 1949 at a minimum. See “Cinderellas Face Greenville Team,” Monroe (Louisiana) Morning World, April 25, 1948: 10, and large ad for a game in the Delta Democrat-Times, May 1, 1949: 5.

9 “Girl Star with Creoles Sunday,” Delta Democrat-Times (Greenville, Mississippi), April 6, 1950: 6. The other three infielders were Alvin Taylor, Mike Hobbs, and Johnny Green. Jennings’ planned outfield was Big Mules Depha, Charlie Walton, and Ike Newsom, but his battery was to be determined. See also “Orleans Creoles Beat Giants, 5-1,” Delta Democrat-Times, April 10, 1950: 7. Attendance was estimated at 300.

10 Paul Borden, “Royals’ White Not Fond of Magnolia Memories,” Jackson (Mississippi) Clarion-Ledger, March 11, 1986: 19.

11 White, 24.

12 White, 25.

13 White, 28, 37.

14 White, 25, 28, 39.

15 See kcpublicschools.org/Page/1016.

16 Porter, 1660.

17 White, 29, 39, 238.

18 White, 37.

19 White, 31, 41, 44. During the 1970s he attended Metropolitan Community College-Longview in Lee’s Summit, Missouri. See Christina Medina, “Video: MCC Is Proud to Call Royals Hall of Famer Frank White an MCC Alumnus,” June 30, 2015: blogs.mcckc.edu/newsroom/2015/07/30/100-years-100-stories-frank-white-mcc-is-proud-to-call-frank-white-an-mcc-alumni/.

20 “Kauffman Has Academy Plans,” Panama City (Florida) News, September 12, 1969: 2B. For more information, see Richard Peurzer, “The Kansas City Royals’ Baseball Academy,” The National Pastime, Number 24, 2004: 9-10.

21 White, 41.

22 White, 42.

23 White, 42-43.

24 Ed Fowler, “Royals Line up 15 for Academy,” Kansas City Times, July 4, 1970: 17. In his autobiography White described his academy experience in detail (pages 44-51).

25 “Academy Starts with 10-0 Victory,” Kansas City Times, September 8, 1970: 36.

26 “Royals Baseball Academy to Hold Tryouts in P.C.,” Playground Daily News (Fort Walton Beach, Florida), June 4, 1971: 13.

27 “Academy Sends 14 Into System,” Kansas City Times, April 13, 1972: 57.

28 White, 51-52.

29 “Royals Call Frank White,” Kansas City Times, June 12, 1973: 23.

30 White, 53-54. At baseball-reference.com/boxes/BAL/BAL197306120.shtml it shows two balls were hit to him. In the bottom of the eighth inning he threw out Al Bumbry on the first, but in the bottom of the ninth Tommy Davis reached on an infield single hit toward White. White wasn’t charged with an error in his debut.

31 White, 54. He said Drago broke Chambliss’s hand but Chambliss didn’t leave the game, nor did he miss any time in subsequent games. However, Chambliss remained in a prolonged slump and went a week without driving in a run. See “Aspro Knows Feeling,” Sandusky (Ohio) Register, June 26, 1973: 24.

32 White, 59-60, 67.

33 “Dream Comes True for KC’s ‘Academy Frank,’” Neosho (Missouri) Daily News, June 28, 1973: 11. In the article he named two baseball idols, Hank Aaron and Jackie Robinson, though on page 53 of his 2012 autobiography White said he chose uniform number 20 because Frank Robinson was his favorite player.

34 “Frank White Sent to Omaha,” Kansas City Times, July 21, 1973: 51.

35 Gib Twyman, “Royals Keep ’Em Down with Farm,” Kansas City Times, September 19, 1973: 26.

36 White: 54-56.

37 See baseball-reference.com/players/event_hr.fcgi?id=whitefr01&t=b.

38 See baseball-reference.com/leagues/AL/1975-specialpos_2b-fielding.shtml.

39 White, 75-76.

40 White, 77.

41 White, 108.

42 White, 160.

43 White, 78.

44 Steve Doyle, “White Shines Bright,” Jackson (Mississippi) Clarion-Ledger, October 20, 1980: 6B. The article started on page 1B. Not surprisingly, White wrote at length in his autobiography about the 1980 postseason. See pages 83-91 about that ALCS and pages 21-22 and 92-95 about the World Series.

45 See kansascity.royals.mlb.com/kc/history/awards.jsp and https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/w/whitefr01.shtml#all_leaderboard.

46 See baseball-reference.com/players/w/whitefr01.shtml#all_leaderboard.

47 White, 12.

48 White, 14-15.

49 See mlb.com/news/don-denkinger-players-recall-blown-call-in-1985-world-series/c-99040244.

50 kchistory.org/week-kansas-city-history/championship-season.

51 White, 19.

52 See mlb.com/royals/hall-of-fame/members/frank-white.

53 See kansascity.royals.mlb.com/kc/history/awards.jsp and slugger.com/en-us/silver-slugger-awards.

54 “All-Stars Top Japan,” Daily Sitka (Alaska) Sentinel, November 3, 1986: 6.

55 White, 163.

56 See mlb.com/royals/hall-of-fame/members/frank-white.

57 “Blue Jays Thump KC; White Gets 2,000th Hit in Loss to Toronto,” Macon (Missouri) Chronicle-Herald, September 12, 1990: 2.

58 Gib Twyman, “Royals Bobble Ball with Treatment of White,” Salina (Kansas) Journal, October 30, 1990: 11.

59 See mlb.mlb.com/kc/team/exec_bios/white_frank.jsp.

60 White, 125, 191.

61 See mlb.mlb.com/kc/team/exec_bios/white_frank.jsp.

62 White, 34, 138.

63 White, 147. He also engaged with the RBI program a decade later; see David Brown, “Former Player White Gives Kids a Boost at Clinic,” July 15, 2017, mlb.com/news/royals-frank-white-helps-kids-at-rbi-clinic/c-242376764.

64 See Jason M. Vaughn, “Royals Boot Frank White Off Broadcast Team,” WDAF-TV, December 2, 2011; fox4kc.com/2011/12/02/frank-white-out-of-royals-broadcast-team/.

65 White, 35, 174, 241.

66 See baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Frank_White.

67 See Jeff Passan, “Why Royals Great Frank White No Longer Associates with the Team Whose Stadium He Built,” Yahoo Sports, October 19, 2014; sports.yahoo.com/news/why-royals-great-frank-white-no-longer-associates-with-the-team-whose-stadium-he-built-044453095.html.

68 Karen Kornacki, “Frank White: Return to Kauffman Stadium Was Awesome,” KMBC 9 News, September 1, 2015; kmbc.com/article/frank-white-return-to-kauffman-stadium-was-awesome/3555744.

69 See jacksongov.org/395/County-Executive.

70 See jacksongov.org/794/Royals-White-House-Celebration.

71 For example, see Tom Dempsey, “Records: Jackson County Executive Owes $45,000 in Unpaid Taxes,” KSHB-TV News, September 27, 2018; kshb.com/news/region-missouri/jackson-county/jackson-co-executive-owes-45000-in-unpaid-taxes.

72 White, 98, 166, 213.

73 See ballotpedia.org/Frank_White_Jr.

74 Denny Matthews with Matt Fulks, Denny Matthews’s Tales from the Royals Dugout: A Collection of the Greatest Stories Ever Told (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, LLC, 2004), 106, 107.

75 Jack Etkin, “Royals’ White Isn’t Ready to Quit Just Yet,” Chicago Tribune, October 7, 1990: Section 3, page 8. (Etkin was a reporter for the Kansas City Star at the time.)

Full Name

Frank White

Born

September 4, 1950 at Greenville, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.