Gaylord Perry

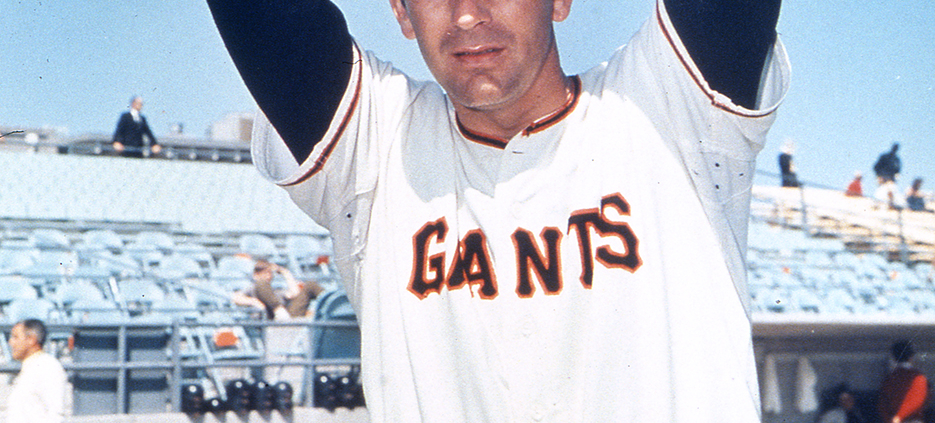

Gaylord Perry, one of the premier pitchers of his generation, won 314 games and struck out 3,534 batters, but his place in baseball history rests mainly with his notorious use of the spitball, or greaseball, which defied batters, humiliated umpires, and infuriated opposing managers for two decades. But make no mistake: he was also a brilliant craftsman with several excellent pitches in his repertoire, a hurler whose mastery of the spitter provided the batter yet another thing to think about as the pitch sailed toward the plate. After the game, he sheepishly denied any wrongdoing, slyly grinning like a poker player who knows he’s one step ahead of everyone else.

Gaylord Perry, one of the premier pitchers of his generation, won 314 games and struck out 3,534 batters, but his place in baseball history rests mainly with his notorious use of the spitball, or greaseball, which defied batters, humiliated umpires, and infuriated opposing managers for two decades. But make no mistake: he was also a brilliant craftsman with several excellent pitches in his repertoire, a hurler whose mastery of the spitter provided the batter yet another thing to think about as the pitch sailed toward the plate. After the game, he sheepishly denied any wrongdoing, slyly grinning like a poker player who knows he’s one step ahead of everyone else.

During Perry’s career, the rules governing the enforcement of the spitball were changed twice, and the umpires were given explicit directives concerning the pitch several other times, and all this was primarily because of Gaylord Perry. When it was his day to pitch, he was the story. Where did he get his grease? Why don’t the umpires stop him? Did you see what that pitch just did? Perry just kept grinning. The only time the ruckus quieted down, he reasoned, was when he was pitching poorly. The louder it got, the better he was doing. Sure, there were many other accused practitioners of the spitter during the 1960s and 1970s — good pitchers like Phil Regan, Bill Singer, Jim Maloney — but no one threw it as well, and for as long, as Gaylord Perry.

Through the years, Perry’s denials became a familiar and humorous part of the show. During a playoff game in 1971, a television reporter briefly sat down with the Perry family during a game Gaylord was pitching. After a few polite questions, Allison, Perry’s five-year-old daughter was asked, “Does your daddy throw a grease ball?” Not missing a beat, she responded, “It’s a hard slider.”

Gaylord Jackson Perry was born September 15, 1938, to tenant farmers Evan and Ruby. Gaylord’s older brother James also had a long major league pitching career, and younger sister Carolyn completed the family. Evan Perry was a great athlete who played both baseball and football, and reportedly turned down a minor league contract because his family could not afford to have him leave their farm. Evan and Ruby had a 25-acre parcel of land, where they grew tobacco, corn and peanuts for money (sharing half with the landowners), and raised animals and additional vegetables to feed their own family.

Gaylord and Jim began plowing the fields with a mule at the age of seven, and Gaylord’s earliest childhood memories were of working on the farm and wanting to be a cowboy. The Perry boys were luckier than most-their father loved baseball and gave them as much free time as practical so that they could pursue the game. Jim and Gaylord both began playing ball with their father during their lunch break, and later all three played on the same local semi-pro team.

Gaylord attended Williamston High School, and starred in football, basketball and baseball. On the gridiron, he was All-State as an offensive and defensive end as a sophomore and junior, before giving up the sport because he did not want an injury to affect his baseball career. On the hardwood, Gaylord teamed with his brother Jim (both Perrys were already 6-foot-3) to reach the state finals in Gaylord’s freshman year. Jim, two years older, moved on to Campbell Junior College after his own junior year. In four years of basketball, Gaylord averaged nearly 30 points and 20 rebounds per game, and led his team to a 94-8 record. He turned down dozens of college scholarship offers.

But baseball remained his favorite pastime. Gaylord began his high school years as a third baseman, affording him a great view of brother Jim’s talents on the mound. Near the end of Gaylord’s freshman year, the coach began swapping the Perrys to give Jim’s arm a rest. Williamston High won the state tournament, with the Perry brothers tossing back-to-back shutouts to sweep the best-of-three finals.

After three more outstanding seasons, winning 33 of 38 decisions, Gaylord was ready to turn professional. Accordingly, local officials arranged an exhibition game against ex-big-leaguer Tommy Byrne and assorted local semi-pros, a contest designed to showcase Perry for major league scouts. He won the game, 5-1, at one point striking out 17 consecutive batters. Perry was hoping to sign with the Indians, through whose system his brother Jim was climbing, but Cleveland dropped out of the bidding early. Instead, he signed with the San Francisco Giants, and scout Tim Murchison, for a $60,000 bonus and three-year contract. Gaylord gave half the bonus money to his father, getting his parents out of debt for the first time in their lives, and put the rest in the bank.

(The signing bonus later put Gaylord in hot water with the Internal Revenue Service. Since he and Evan had split the bonus, the two men each paid taxes on $30,000. In 1961 the IRS went after Perry for the remainder of the full share of the tax bill, plus penalties, a debt that Perry, earning a minor league salary, was in no position to pay. He borrowed the money from the Giants, and paid them back when he won a settlement from the government several years later.)

Perry was nearly 20 years old when he graduated from high school in 1958 and signed his big contract, and he was anxious to get started. He was assigned to the St. Cloud (Minnesota) team in the Class-C Northern League. His first professional teammates included Matty Alou and Bob Bolin, and the club was strong enough to capture the league pennant, although they lost in the playoffs. Perry finished 9-5 with a 2.29 ERA, second in the circuit to Aberdeen’s Bo Belinsky. Now fully grown at six-feet-four and 210 pounds, Gaylord spent his second minor league campaign with the Corpus Christi Giants of the Double-A Texas League. This season was a bit disappointing, as he posted a 10-11 record and a 4.05 ERA.

Early in his high school years, Gaylord took an interest in a girl named Blanche Manning, the star of the girls’ basketball team. The two teams played doubleheaders and traveled to out-of-town games on the same bus, giving Perry ample courting time. Blanche was also an outstanding student, and went off to Duke University while Perry was a senior in high school. The couple married on December 26, 1959.

In 1960 Perry returned to the Texas League, although the Giants had moved their affiliate to Harlingen and named the squad the Rio Grande Valley Giants. The Giants won the pennant, but Perry himself was snake-bitten. He led the circuit with a 2.83 ERA, but somehow managed to finish just 9-13.

For the 1961 season the Giants assigned Perry to Tacoma of the Pacific Coast League, one step away from the majors. He began the season with two five-hit shutouts, and had another excellent season, finishing 16-10 with a 2.55 ERA. His win total tied him for the league lead with teammate Ron Herbel, and his ERA was third best. At the end of the season, he was placed on the major league 40-man roster for the first time.

A strong showing in the spring of 1962 landed Perry a role as the 10th man on the Giants’ staff, as a spot starter and reliever. His first assignment was a start in the Giants fifth game, but he left in the third with the game tied at four. He picked up his first victory in his next start, on April 25, hurling five innings of a 5-2 victory against the Pirates, then four-hit Pittsburgh on the 30th. This early success proved fleeting, and his ensuing struggles led to sporadic use for two months. Sporting a 6.25 ERA, Perry was sent back to Tacoma on June 11.

Gaylord had another strong half-year in the PCL, finishing 10-7 with a league-leading 2.48 ERA. This second hitch in Tacoma garnered him the endorsement of Carl Hubbell, the Giants’ farm director: “He’s gotten around to throwing that good fast ball of his more frequently, which makes his other pitches more effective. He’s acquiring the stuff which will enable him to win consistently with the big club.” His manager, Red Davis, was equally positive: “When Gaylord goes back, he’ll stick and he’ll win big.”

When the 1962 PCL season ended, Perry was called back up to San Francisco, right in the middle of an historic pennant race. Gaylord pitched sparingly the last few weeks of the season, finishing (counting his early season trial) with a 3-1 record and a 5.23 ERA in 13 games. Nonetheless, he was summoned in the bottom of the ninth inning of the second game of a best-of-three playoff series with the Dodgers to decide the NL pennant. It was a 7-7 tie with two on and nobody out, and manager Alvin Dark told Perry to expect a bunt from the next hitter, Daryl Spencer, and to throw to third to force Maury Wills. Perry got the bunt right back to him, but decided that Wills would beat the throw and instead threw to first for the safe out. Dark was incensed, complaining to reporters after the game about the brain lock that his rookie pitcher supposedly endured. Wills scored the winning run two batters later, though the Giants gained the pennant by winning the third game the next day. Gaylord was not eligible to pitch in the ensuing World Series, which the Giants lost to the Yankees in seven games. With his half-share of the Series money, he put a down payment on a farm near his family’s place.

The 1963 season was a disappointment. Perry spent most of it in the Giants bullpen, used erratically and seldom, appearing in 76 innings and posting a 1-6 record with a 4.03 ERA. He was sent back down to Tacoma in August, but pitched just one game (a three-hit victory against Salt Lake City) before getting recalled to San Francisco when Jim Duffalo split a finger. Perry’s lost season was salvaged somewhat with a fine winter playing in the Dominican Republic, joining teammates Juan Marichal and all three Alou brothers – Felipe, Matty, and Jesus. After a rocky start, he ended up leading the league in strikeouts.

That winter, the Giants pulled off a big trade with the Milwaukee Braves, dealing outfielder Felipe Alou, catcher Ed Bailey, pitcher Billy Hoeft, and infielder Ernie Bowman for catcher Del Crandall and pitchers Bob Shaw and Bob Hendley. As Perry was hanging on at the bottom of the Giant pitching staff, he was obviously not anxious to see the team acquiring more hurlers. The deal turned out to be fortuitous nonetheless. Bob Shaw, it seems, threw a heck of a spitball.

Although the “spitball” had been formally outlawed in 1920, allowing a few practitioners to continue to throw it until they retired, countless hurlers were rumored to have applied saliva or otherwise doctored the ball in every succeeding season. Hitters complained, managers protested, but for the most part pitchers could do just about anything to the ball, providing that no one could prove they did it. In fact, hurlers could lick their fingers while standing on the mound, as long as they wiped them off, or at least pretended to. Throwing an effective spitball, one that approached the plate like a fastball but suddenly sank like a stone in water, took skill and practice. But getting away with doing so was pretty easy.

The spitter was a hot topic in the 1960s, more so than at any time since its abolition. Ford Frick, baseball’s Commissioner, pushed for its legalization, and he had the backing of Cal Hubbard, the supervisor of umpires, AL president Joe Cronin, and countless other dignitaries. The Sporting News, still baseball’s bible, favored its legalization repeatedly in its pages. The umpires and bureaucrats wanted to change the rule because they were not capable of enforcing it, and it had become an embarrassment.

Burleigh Grimes, the last legal spitballer, said that there were more spitters being thrown in the 1960s than back when it was legal. Estimates for the number of pitchers who threw a “wet one” in the big leagues ran as high as 50. Every time a pitcher went on a hot streak, whether it be Don Drysdale or Juan Marichal, he was accused of throwing illegal pitches. Bob Shaw, the new Giant, was one of the more nefarious practitioners. Upset at Shaw’s offerings one 1964 day, Milwaukee manager Bobby Bragan ordered his pitchers to throw nothing but spitballs for the last six innings of a game to show that umpires didn’t care about enforcing the rule. In another Shaw outing, Philadelphia manager Gene Mauch coached third base to get a better look, and asked the umpires to inspect the ball every time he saw something suspicious.

Gaylord came to camp in 1964 determined to make the starting rotation, and worked with pitching coach Larry Jansen on a new slider, to augment his fastball, curveball, and change of pace. Secretly, he also learned to throw the spitball under the tutelage of Shaw. Perry began using it in batting practice, and in a few spring training games.

In relating the story of Gaylord Perry, it is important to keep in mind that he spent most of his career denying that he did anything illegal. When he finally came clean in a 1974 book, he also claimed that he had put his evil ways behind him, and that his confessions related only to sins of the past. Although the accusations against him slowed down not a whit after his revelations, he continued his denials for the rest of his career and beyond. In fact, he has occasionally indicated that the book itself was just part of his grand deception, that perhaps he never threw anything illegal in his life. There were easily 100 contemporaries of Perry who were accused of doctoring the baseball at some point. But no one compared to Perry, either in the quantity and intensity of the accusations, or in the skills he brought with him to the mound.

According to Perry’s book, the first time he ever threw an important illegal pitch was on May 31, 1964 against the Mets in Shea Stadium. It was the second game of a doubleheader, a game that went 23 innings and lasted a record 7 hours and 23 minutes. Perry, the classic mop-up reliever, took over for the Giants in the bottom of the 13th of the 6-6 game. He had tossed an occasional spitball in meaningless situations, but on this day he and catcher Tom Haller decided it was time to try it out with the game on the line. Perry responded with 10 shutout innings to earn a victory, and to finally earn the confidence of manager Dark. With his two new pitches, the slider and the spitter, Perry turned in his first good season, finishing 12-11 with a 2.75 ERA throwing in a variety of roles.

With expectations high for 1965, Perry next took a step backwards. Beginning the year in the starting rotation for the first time, he soon lost his job and struggled to finish 8-12 with a grisly 4.19 ERA. He also began to draw attention to himself with his poor attitude: he argued with umpires, complained about errors made behind him in the field, and called up to the press box to try to get an opponents’ hit changed to an error on one of his teammates. Although Perry was apologetic after being called out by his new manager, Herman Franks, he continued to draw the ire of his teammates throughout his career. Gaylord did not tolerate fielding mistakes.

Perry came to spring training in 1966 as a 27-year-old with 24 major league victories, and no definite role on the Giants’ pitching staff. Accordingly, he reported three weeks early and had a great exhibition season, leading the Cactus League with a 5-0 record. Perry was always a tireless worker, running and throwing regularly between starts, but this spring he worked as he never had before. He also began his practice of playing pepper before his own games, believing that he pitched better once he had worked up a sweat.

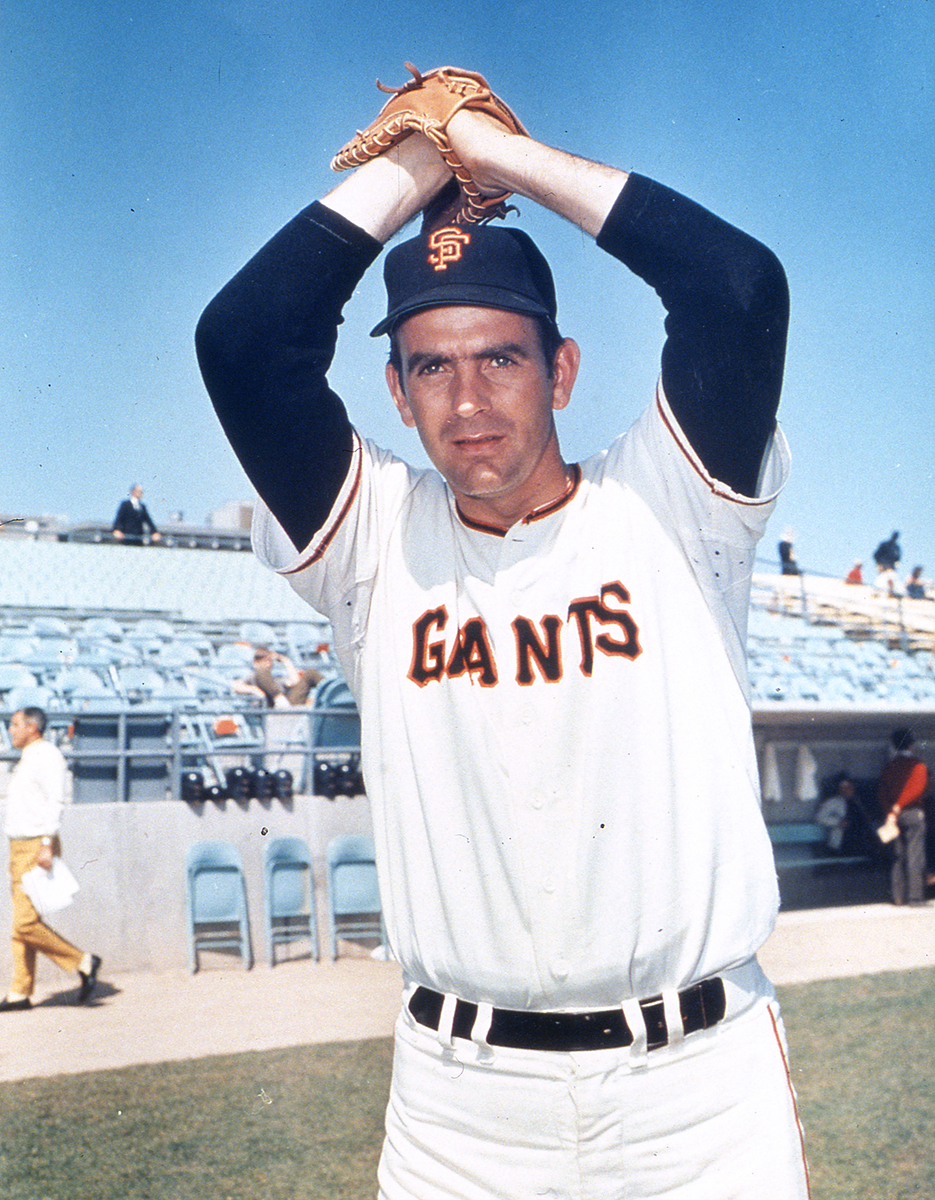

He pitched once in relief on April 19 before getting a start on April 23 in the Giants’ 11th game. It was a great beginning-he bested the Astros 2-1 with a four-hitter, and was soon taking a regular turn in the Giants’ rotation. Perry credited pitching coach Larry Jansen for teaching him the hard slider, and for getting him to throw straight over the top rather than with a three-quarters motion. His pitching repertoire now included two sliders, a fastball, a change of pace, a curveball, and a spitter, and he threw them all with accuracy.

And he began winning. Although sidelined for 15 days after jamming his foot on a slide in early June, by the All-Star break Perry had compiled a 12-1 record with a 2.51 ERA and was an easy selection for the game, held in St. Louis’ newly opened Busch Stadium. To top it off, he earned the victory by pitching two scoreless frames and watching when Maury Wills singled home the winning run in the bottom of the tenth inning.

After a loss on July 14, Perry ran off eight more victories to bring his record to 20-2 on August 20. His best game was likely on July 22, when he two-hit the Phillies and struck out 15, one shy of the franchise record set by Christy Mathewson in 1903. Perry went through a rough patch after winning his 20th game, dropping his next six decisions and finishing at 21-8 2.99. He did pitch a few good games during this stretch, but his struggles contributed to the Giants’ losing the pennant by one-and-a-half games to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Despite the late fade, 1966 was the breakthrough people had long predicted for Gaylord. His win total trailed only Sandy Koufax and Juan Marichal, and he finished second to Koufax in voting for The Sporting News Pitcher of the Year award. Another sign of Perry’s newfound success is that, for the first time, he began to be accused of moistening the baseball. The first documented complaint came in July when Milwaukee manager Bobby Bragan, backed up by outfielder Henry Aaron, complained about Perry’s offerings.

By the mid-1960s, support for legalizing the spitball had waned because offense was in such decline, reaching its lowest levels since the 1910s. Many of the writers who thought the pitch harmless just a few years earlier were beginning to write that the spitball was one of the primary causes of the dearth of run scoring. There were more and more calls instead to tighten up on the enforcement of the rules, to tip the balance more in the direction of the hitter.

Over the next couple of seasons, Perry continued to pitch great baseball but had less success winning games. In 1967 he posted a 15-17 record despite finishing among the league leaders with a 2.61 ERA, 293 innings pitched, 230 strikeouts, and 18 complete games. (As a point of contrast, teammate Mike McCormick pitched fewer innings and had a higher ERA, yet finished 22-10 and won the Cy Young Award.) Perry lost five times by the score of 2-1. He had particularly bad luck against the team the Giants needed to beat, losing all 5 starts to the Cardinals while recording a 2.33 ERA. On September 1st he tossed 16 shutout innings against the Reds, but received no decision. Perry was distraught: “There is just no way at all for us to go 16 innings and not score one little ol’ run. Or is there?” Apparently there was-the Giants finally pulled out the game, 1-0, when Dick Groat drew a bases loaded walk in the bottom of the 21st inning.

Following the season, the rules committee finally outlawed the practice of a pitcher putting his hand to his mouth anywhere on the pitcher’s mound, instructing the umpire to call a ball upon each infraction. According to Perry’s later confession, spitballers had to learn to use foreign substances like Vaseline or hair tonic, rather than saliva. In Perry’s words, “That rule virtually eliminated the pure spitball in baseball. I had the whole winter and spring to work out an adjustment. It wasn’t easy.” Prior to the rule change, Perry would touch his cap and mouth, and fake a wipe of his fingers. Now he had to get his moisture somewhere else on his person, and also learn a new series of elaborate decoy moves. He spent the winter practicing in front of the mirror. After a rocky spring training, he managed just fine.

By mid-summer it was obvious that the new rule had not decreased the illegal pitches at all, but merely added the new mystery of where the pitcher was hiding the lubricant. Perry was first searched in late June when Phillies’ manager Bob Skinner demanded that Gaylord’s ears be searched. A month later, Leo Durocher asked that Perry’s hair and cap be examined. On another night, first base umpire Al Barlick sneaked up behind Perry and yanked his hat off his head. This action was always particularly shocking because Perry was already nearly bald by this point.

In 1968 Perry’s ERA dropped to 2.45 while his record only inched up to 16-15. (Teammate Juan Marichal posted a nearly identical ERA, 2.43, while finishing 26-9.) This season was the low water mark for baseball’s offensive depression, as the National League’s ERA dropped to 2.98. During the month of July Perry posted a 2-5 record despite a 1.59 ERA. The highlight of his season was a no-hitter he threw against the Cardinals on September 17. The opposing pitcher was Bob Gibson, who pitched a four-hitter himself, but lost 1-0 on Ron Hunt‘s first inning home run, one of two round-trippers Hunt hit the entire season. The classic contest took just 1 hour and 40 minutes to complete. Amazingly, the Cards’ Ray Washburn no-hit the Giants the very next day, the first time back-to-back no hitters were pitched in a series. It was, indeed, the year of the pitcher.

In June of 1969, National League president Warren Giles instructed umpires to immediately remove any pitcher from the game if convinced the hurler was putting any lubricant on the ball. Two days later, with Perry on the mound against the Mets, Doug Harvey threw out several balls, checked Perry’s uniform and cap, and found nothing. A few weeks later, Ed Sudol made Perry pull his pants legs up over his knees to be checked. Soon thereafter, umpire Chris Pelekoudas wiped Perry’s face and neck with a towel. Eventually Giant general manager Chub Feeney complained to the league office about the harassment, and the protests slowed down.

The major leagues also reduced the strike zone and lowered the pitching mound in 1969, but Perry did not seem to be affected. His ERA stayed steady at 2.49, and he managed a 19-14 record, including 26 complete games and a league-leading 323 innings pitched. He also slugged his first ever big-league homer on July 20 off Claude Osteen. An oft-told story claims that Alvin Dark had once suggested that man would walk on the moon before Gaylord hit a home run; in fact, Neil Armstrong did step on the moon just prior to Perry’s grand hit. Interestingly, Perry hit five more home runs in his career, and his hitting record was not particularly unusual for a pitcher of his era.

The next season Gaylord’s ERA rose to 3.20, but he received enough offensive support this time to manage a record of 23-13. He finished strong, tossing four straight shutouts in September. Perry’s 23 wins led the league, as did his 41 starts and 328⅔ innings, and he finished second to Bob Gibson for the league’s Cy Young Award. His brother Jim won 24 games for the Twins that season, making the Perrys the first brothers to win 20 in the same season.

Gaylord followed up his big season with a 16-12 record and 2.76 ERA in 1971. He was involved in a bit of history on April 27 when he gave up Henry Aaron’s 600th home run, only the second time Aaron had homered off him. Aaron victimized Perry two more times, once in the 1972 All-Star game, and again in 1975 for Aaron’s first American League home run, the 734th of his career. In October Perry pitched in the post-season for the first and only time in his career, beating the Pirates in the first game of the playoffs before losing the clincher in Game 4 of the best-of-five series.

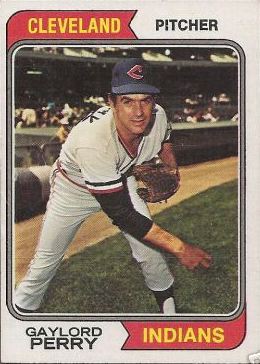

After the 1971 season Perry was traded to the Cleveland Indians, with infielder Frank Duffy, for pitcher Sam McDowell. McDowell was a talented, though frustrating, left-handed hurler, and four years younger than Perry. Most observers felt that that the Giants had made a great deal. They were seen as an aging team, and would soon part ways with Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Juan Marichal.

Joining the American League, Perry traded one set of protagonists for another, and if anything, the circus atmosphere surrounding his starts rose to a new level. In an early season game against the Athletics, Mike Epstein waved his bat at Perry and threatened to head for the mound. Perry was strip searched after a protest by A’s manager Dick Williams, and ordered to change shirts. Billy Martin brought a bloodhound to a game to sniff baseballs. In late August, Indians general manager Gabe Paul protested the treatment of Perry to league president Joe Cronin, who asked the umps to back off.

Through it all, Perry’s pitching was sensational in 1972. Pitching for a fifth-place Indians club that scored just 3.0 runs per game, Perry’s 1.92 ERA led him to a 24-16 record. He was a workhorse, tossing 342⅔ innings over 41 games, completing 29 of his starts. Eight times he pitched into extra innings for his poor-hitting teammates. Historian Bill James believes this was the best season by an American League pitcher since Lefty Grove in 1931. He was rewarded with the Cy Young Award even though one writer said publicly that he would not vote for Perry because of his illegal pitch. In any event, Gaylord edged Wilbur Wood 64-58 in the balloting.

In June of 1973, literally taking matters into his own hands, Yankee manager Ralph Houk charged the mound, pulled the cap from Perry’s head, tossed it on the ground and kicked it. After the game, in which third base coach Dick Howser was ejected during another greaseball allegation, Yankee outfielder Bobby Murcer lamented, “If the league president or commissioner had any guts, they’d ban the pitch.” Murcer was fined for his comments, but did not back off.

Did he or didn’t he? Perry relished the controversy, and did everything he could to make the hitter think he was throwing it on nearly every pitch. According his book, he could go entire games, or a series of games, without using the spitter. If his sinker, or later his forkball, was working, he didn’t need any help. He also perfected the application enough so that he only needed a bit of natural sweat. He continued to go through his elaborate series of feints with his hand, rubbing his neck, his cap, his belt, his glove, whether or not he had any intention of wetting the ball. “I don’t even have to throw it anymore,” he said, “because the batters are set up to believe it’s there, waiting for ’em.”

Not everyone was concerned. AL umpire Bill Haller said, “I watched Gaylord like a hawk. He never goes to his mouth. I never see him get any foreign substance. When we umpire, we check balls as well as the catcher’s glove. I’ve never found anything. I’ll tell you what he’s got: a good curve, a fine fastball, a good change, and a fine sinker. His sinker is the suspicious one. It’s excellent. But no better than Mel Stottlemyre‘s and they don’t complain about his. I’ll tell you what Perry is: he’s one helluva pitcher, a fantastic competitor.”

Perry struggled a bit more often in 1973, finishing 19-19 (winning his final four starts) for the last-place Indians, with a 3.38 ERA. After he shut out the Tigers on August 30, manager Billy Martin told the writers that he had ordered his pitchers to throw spitballs the last two innings: “The umpires are making a mockery of the game by not stopping Perry. Everyone knows he does it, but nobody does anything about it. We’re going to keep on doing it every time he pitches against us.” To emphasize his point, Martin called Joe Cronin and Bowie Kuhn, “gutless.” Cronin suspended Martin for three days, but before the suspension was up the Tigers fired him. A week later, Martin was managing the Texas Rangers.

After the 1973 season, the Indians and Red Sox worked out a deal for Perry in which the Indians would receive pitchers Marty Pattin, John Curtis and Craig Skok. Both general managers agreed to the swap, and the Red Sox had scheduled a press conference to announce it, but the Indians’ board of directors overruled the trade. The Red Sox subsequently pulled off a big deal with the Cardinals, angering the Indians, who believed the deal could be resurrected.

In the spring of 1974, Perry and Bob Sudyk released their book, Me and the Spitter, An Autobiographical Confession. Perry told the story of how he learned the pitch, and numerous tales of particular confrontations with angry batters. “I reckon I tried everything on the old apple, but salt and pepper and chocolate sauce topping.” But he also said he was through with all such illegalities, writing, “Of course, I’m reformed now. I’m a pure law-abiding citizen.”

In related news, that winter the rules committee gave the umpires the authority to rule a pitch illegal if he thought the pitch behaved like a spitball. The first violation would be a “ball”; the second would result in an ejection. The first time the rule was enforced was on Opening Day, when Marty Springstead called a ball against Gaylord. Properly concerned, in early May the Indians set up a meeting with umpires in the bullpen at Fenway Park so that Perry could demonstrate his forkball to them. The umpires were impressed, and AL president Lee MacPhail sent a note to all league umps saying that Perry’s forkball did, indeed, behave just like a spitter.

After his opening loss, Perry embarked on the greatest pitching stretch of his career, winning his next 15 decisions spread over 17 starts, running his record to 15-1 with a 1.31 ERA by July 3. All 15 wins were complete games, as was the game he finally lost, 4-3 to Oakland in 10 innings. In the game against the A’s he was trying to tie the league record for consecutive victories, but gave up a run in the ninth to knot the score before losing in the next frame. Perry returned to earth in the second half, finishing 21-13 with a 2.51 ERA for the fourth-place club.

Perry’s great season was also spiced with regular complaints about his team’s defense, especially that of young center fielder George Hendrick. At one point Perry told manager Ken Aspromonte that he didn’t want Hendrick playing behind him again, and Aspromonte actually obliged a few times. On one occasion when both Perry and Hendrick were in the listed starting lineup, Hendrick refused to play and left the ballpark.

On September 12 the Indians made headlines by sending two players and cash to the California Angels for 38-year-old slugger Frank Robinson. Although Robinson had hit 20 home runs as the Angels’ designated hitter that season, his days as a star player were over. Rumors began to swirl that Robinson was actually acquired to become the team’s new manager. Before such a thing could happen, Perry was more interested in Robinson’s $173,500 contract, and told reporters that for his next deal he would demand “one dollar more than Robinson is getting.” His new teammate didn’t appreciate the comment, and the two had to be separated to avoid a fistfight. Perry later said that he wanted to be traded if Robinson was named the manager, which Robinson was at the conclusion of the season.

Robinson’s appointment was a huge story, as he was the first African-American skipper in major league history. Unfortunately, he began his managerial career in an uncomfortable feud with his only star player, a feud that was not destined to end. Although the two brokered a public peace during the off-season, the trade rumors soon took over the club. The Red Sox in particular spent the winter and the early part of the 1975 season trying to acquire the star pitcher.

In spring training Perry and Robinson argued over the manager’s enforced training regimen, and specifically that Perry would not be allowed to do his own routine. Perry wanted to run sprints, rather than the long foul-line-to-foul-line runs that Robinson imposed. Gaylord was used to special privileges, however: “I’m not training for a marathon race, and I’m not about to let some superstar who never pitched a game in his life tell me how to get ready to pitch.” Things continued along these lines well into the season. Perry’s departure became a foregone conclusion, and the story took some of the luster away from Robinson’s historic managerial debut.

Perry struggled for the Tribe in early 1975, attaining a record of 6-9 with a 3.55 ERA into mid-June. On June 13, he was finally dealt to Texas for pitchers Jim Bibby, Jackie Brown, Rick Waits, and $150,000. His new manager, ironically, was Billy Martin, who had been miraculously transformed: “I realize how wrong I was. I’d like to get on the record immediately as saying Gaylord does nothing illegal.” On the other hand, when Perry faced his old Indians team on June 15, Frank Robinson told reporters that, alas, Perry did throw a greaseball on occasion and that Robinson was prepared to protest if he saw any such pitches. Perry’s regular team-swapping in the latter half of his career led to several such changes of heart on the part of his new and old managers.

Perry was hit hard in his first few starts, but settled down to finish 12-8, 3.03 for Texas. He was the Rangers’ best pitcher, and still a workhorse, hurling over 300 innings combined for his two employers. By the end of the season, Martin had been fired by the Rangers and then hired by the Yankees, where he was free to resume his crusade against Perry’s dastardly pitch.

The next season Gaylord posted a 15-14 record with a 3.24 ERA. Though he was now 38 years old, after the 1976 season Texas surprised many observers by protecting Perry in the expansion draft. Owner Brad Corbett reasoned, “Gaylord’s value to this team is much more than just as a pitcher.” In 1977 the Rangers finished a surprising second, and Perry (15-12, 3.37) was a big contributor to their success. Texas had put together a solid group of starters around Perry, including Bert Blyleven, Doyle Alexander, and Dock Ellis.

By this point in his career, Perry was spending his off-seasons near his boyhood home. Earlier in his baseball years, Perry sold insurance during the off-season. By the late 1960s, he and Blanche and their four children (three daughters and a son) lived in the Bay Area, and Gaylord sold cars for an auto dealership. By the middle 1970s, the Perrys had moved back to North Carolina for good, and Perry spent his off-seasons living and working on his farm.

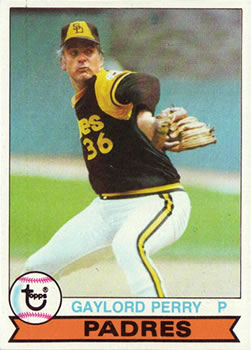

In February 1978, the 39-year-old Perry was dealt to the Padres for Dave Tomlin and $125,000. Like the Indians three years earlier, the Rangers needed the money, including the savings from Perry’s $200,000 contract, and wanted to get younger players. The Padres, on the other hand, felt they needed a veteran pitcher to stabilize their young pitching staff. Gaylord delivered, posting a record of 21-6 with a 2.73 ERA, as the Padres finished 84-78, the best record of their 10-year existence. Perry became the third hurler to win 20 games for three different teams, following Carl Mays and Pete Alexander. He also won his second Cy Young Award, becoming the first hurler to capture the award in each league. As a small concession to age, Perry showed a willingness to leave the game to the bullpen, and completed just five games.

In February 1978, the 39-year-old Perry was dealt to the Padres for Dave Tomlin and $125,000. Like the Indians three years earlier, the Rangers needed the money, including the savings from Perry’s $200,000 contract, and wanted to get younger players. The Padres, on the other hand, felt they needed a veteran pitcher to stabilize their young pitching staff. Gaylord delivered, posting a record of 21-6 with a 2.73 ERA, as the Padres finished 84-78, the best record of their 10-year existence. Perry became the third hurler to win 20 games for three different teams, following Carl Mays and Pete Alexander. He also won his second Cy Young Award, becoming the first hurler to capture the award in each league. As a small concession to age, Perry showed a willingness to leave the game to the bullpen, and completed just five games.

Back in San Diego for the 1979 season, Perry had another solid campaign, managing a 12-11 record with his 3.06 ERA. Unfortunately, he became disillusioned with the direction of the team, and at different times publicly criticized manager Roger Craig and general manager Bob Fontaine. Early in the season he called out Craig for playing Gene Richards in center field, causing the skipper to complain that Perry put a lot of pressure on the team by constantly criticizing their defense. After a couple of mistakes cost Perry a game in May, the veteran pitcher fumed, “Fielders are supposed to make plays in the big leagues. We’re giving games away.”

In August, Texas owner Brad Corbett was quoted saying that trading Perry was the biggest mistake he made in baseball, and said that he had promised Perry a front office position at the end of his career. Likely crossing the line to tampering with the Padres player, Corbett also indicated that he wanted to reacquire Perry. In late August, Perry informed the Padres that he wanted to be traded, preferably back to Texas. On September 4, he took it a step further by quitting the team, saying he would retire unless a deal could be worked. The Padres were justifiably upset, since Perry had recently extended his contract through 1980. After spending a few months trying to get their star to reconsider, they reluctantly dealt Perry back to the Rangers in February 1980.

Texas did not prove to be the cure-all for Perry’s ills. In June manager Pat Corrales warned Gaylord to stop criticizing his teammates, and later chastised his pitcher for storming off the mound when being taken out of the game. Perry had the best ERA on the staff, 3.43, but only managed a 6-9 record in 24 starts. On August 24 he was dealt to the Yankees for pitcher Ken Clay, putting Perry in his first pennant race since 1971. He finished the season 4-4 for the division-winning Yankees, but did not pitch in the team’s three-game playoff loss to the Royals. After the season the Yankees set the 42-year-old Perry free.

Eleven victories shy of 300, Perry signed with the Braves in January 1981, and finished the season with an 8-9 record. He likely missed out on winning his 300th game with Atlanta because of the player strike that shut down the game for seven weeks in mid-summer. After the Braves let him go, he spent most of the winter without a job before finally signing in March 1982 with the Seattle Mariners. His career victory total then stood at 297.

Perry began the 1982 season with two complete-game losses, then won two straight decisions to get to 299 wins. On May 6, 1982 he hurled a complete game 7-3 victory over the Yankees for the historic #300, becoming the first 300-game-winner since Early Wynn in 1963. Pitching regularly for a mediocre Mariner team, Perry finished 10-12 with a 4.40 ERA over 32 starts and 216⅔ innings.

Other than his 300th win, Perry made his biggest headlines with with his controversial pitch. On August 23, Perry was first warned, then ejected, by plate umpire Dave Phillips for throwing two allegedly illegal pitches. It was the first and only time Perry, a 21-year veteran approaching his 44th birthday, had been kicked out of a ballgame for his famous pitch. Perry threatened legal action before eventually backing down.

Perry finally wound down in 1983, going 3-10 with the Mariners, drawing his release, and then finishing 4-4 with the Kansas City Royals. In keeping with his career-long reputation for skirting the law, Perry had a supporting role in one of the big stories of the 1983 baseball season. On August 18, 1983, teammate George Brett hit a home run at Yankee Stadium that was disallowed because he had too much pine tar on his bat. During the ensuing melee, Gaylord ran out and confiscated the bat, before being chased down by stadium security and promptly kicked out of the game.

At the end of the 1983 season, Perry retired from baseball. His 314 wins were good for 11th on the all-time list at the time, and his 3534 strikeouts placed him third. It took Perry three tries before gaining election into baseball’s Hall of Fame, likely due to the controversy surrounding his pitching repertoire.

His post-career life has had its share of disappointments. Perry’s 400-acre farm failed in 1986, causing him to take a job as a regional representative for Fiesta Foods, a company that made chips and tacos. The following season he signed a four-year contract to create a baseball program at Limestone College in Gaffney, South Carolina.

Tragically, in September 1987, Gaylord’s beloved wife Blanche was killed in a two-vehicle car accident. She was just 46 years old. A few years later Gaylord married Carol Caggiano, a board member at Limestone College. Perry remains close to his four grown children.

In the ensuing years, Gaylord Perry has been able to make a fair living just being Gaylord Perry, touring the country, signing autographs, appearing at ballgames. He was making a comfortable living, and his $100,000 annual major league pension kicked in when he turned 65 in 2003.

Wherever he travels, whether a minor-league game or a baseball card convention, he is repeatedly asked the same questions: “What did you put on the ball?” “Where did you hide the stuff?” “How often did you throw it?” The familiar grin is always accompanied by the same coy denial. Gaylord Perry is still playing with us.

Postscript

Perry died of natural causes on December 1, 2022 at the age of 84.

Sources

In preparing this biography, I relied heavily on hundreds of issues of The Sporting News, available via the Paper of Record web site (www.paperofrecord.com). During the prime of Perry’s career he was mentioned in TSN nearly every week, often more than once. I read every reference to Perry from 1958 to the present. I also relied on Perry’s thick file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. In addition, I used the following, especially including his wonderful autobiography.

Golenbock, Peter. Wild, High and Tight, The Life and Death of Billy Martin. St. Martins Press, 1994.

Perry, Gaylord and Bob Sudyk. Me and The Spitter. Dutton, 1974.

Schneider, Russ. Frank Robinson, The Making of a Manager. Coward, McCann & Gheogegan, 1976.

Photo Credits

SABR-Rucker Archive

The Topps Company

Full Name

Gaylord Jackson Perry

Born

September 15, 1938 at Williamston, NC (USA)

Died

December 1, 2022 at Gaffney, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.