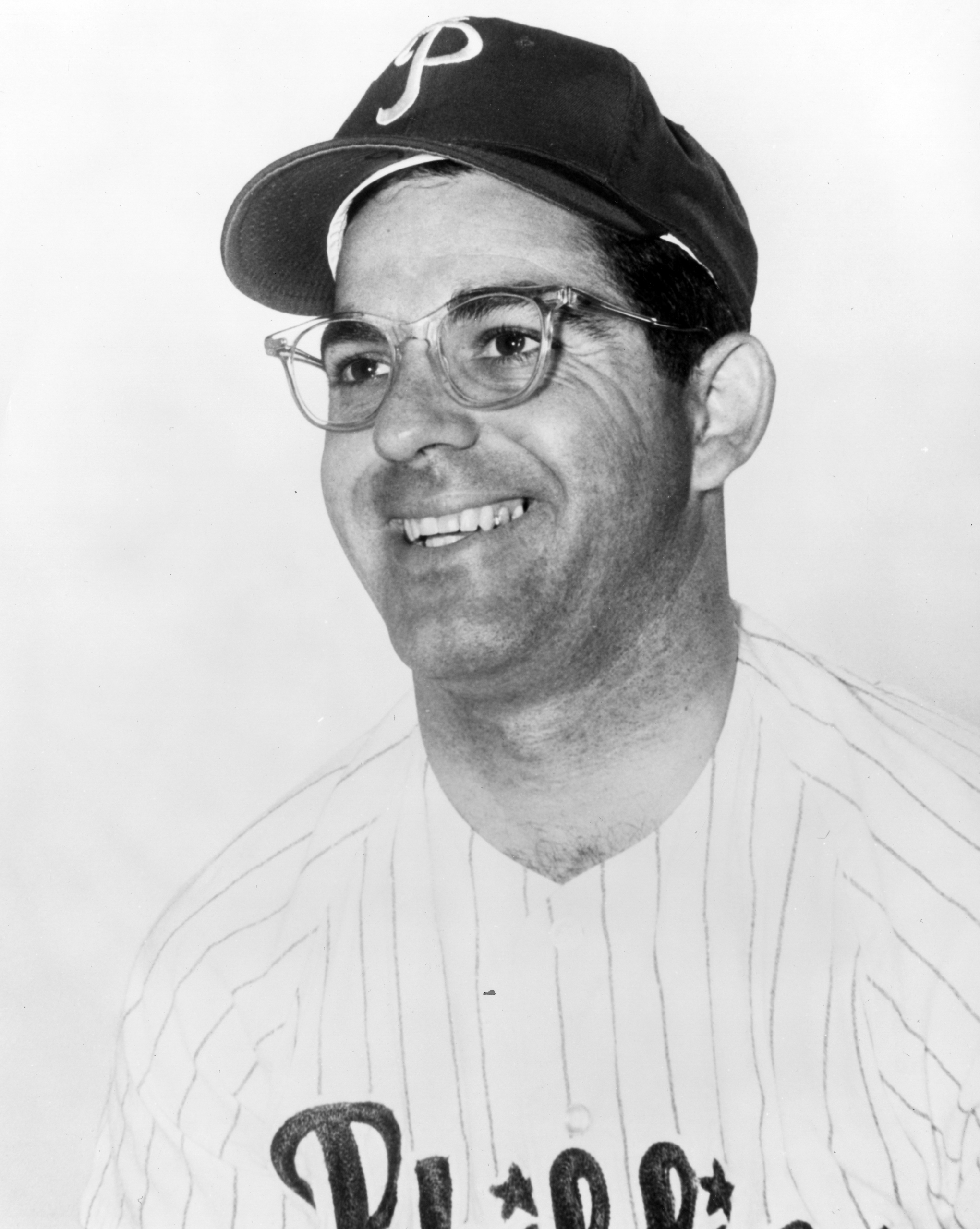

Cookie Rojas

Cookie Rojas is one of a handful of major leaguers who played every position in his career including pitcher. Of that group, he is the only one to make both the American and National League All-Star teams. Rojas worked in the major leagues as a player, coach, manager, and broadcaster for more than five decades. As of 2013, he was still in baseball, working as an analyst for the Miami Marlins’ Spanish-language telecasts.

Cookie Rojas is one of a handful of major leaguers who played every position in his career including pitcher. Of that group, he is the only one to make both the American and National League All-Star teams. Rojas worked in the major leagues as a player, coach, manager, and broadcaster for more than five decades. As of 2013, he was still in baseball, working as an analyst for the Miami Marlins’ Spanish-language telecasts.

Octavio Victor (Rivas) Rojas was born on March 6, 1939, in Havana, Cuba, to an upper-middle-class family. His mother gave him the Spanish nickname Cuqui, meaning charming or adorable, when he was young. The name got anglicized to Cookie when he started in baseball, and stuck with him throughout his long career.

Rojas’s father was a doctor who wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, but Cookie wanted more than anything to play baseball. Rojas was small, slight (listed at 5-feet-10 and 160 pounds), and wore glasses, three things that worked against many promising ballplayers during the 1950s. He wouldn’t give up his dream, and turned himself into a major-league prospect.

The Havana Sugar Kings (Triple A, International League) were a Cincinnati Reds affiliate during the ’50s, and as a result the Reds signed several Cuban players who played for them in the majors. They signed Cookie in 1956, when he was 17, and sent him to their West Palm Beach team in the Class D Florida State League. Cookie made steady if unspectacular progress through the minors, playing at the Reds’ Class C affiliate in 1957 and Class A in 1958. In 1959 the Reds returned Cookie to Havana to play second base for the Sugar Kings, where he teamed with future Reds shortstop and fellow Cuban Leo Cardenas.

The Sugar Kings won the International League title in 1959, but the Cuban revolution interrupted the next season. The Reds moved the franchise to Jersey City, New Jersey, in midseason to avoid the possibility of Fidel Castro nationalizing the team, and Cookie moved with it. He spent 1960 and 1961 with the Jersey City Jerseys while the Reds played Johnny Temple, then Don Blasingame at second base. The Reds won the pennant in 1961 and didn’t bring Rojas to the majors until 1962.

Rojas made his debut as a second baseman in the first regular-season game at Dodger Stadium, on Tuesday April 10, 1962, against the Los Angeles Dodgers’ southpaw Johnny Podres before a crowd of 52,564. He went 0-for-3 though he did lay down a successful sacrifice bunt in the first inning in a 6-4 Reds victory. Rojas was 0-for-4 the following evening against Sandy Koufax. After another hitless game in which he went 0-for-2 with two bases on balls, Rojas was dropped from second in the batting order to eighth, and got his first hit on April 19, in the second inning, a single to center field off Sandy Koufax at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. Rojas saw limited action as a utility infielder and batted only .221 with two extra-base hits in 78 at-bats. The Reds sent him down to Dallas-Fort Worth midway through the season, although Cookie finished the season with the club.

After the season the Reds traded Rojas to the Phillies for relief pitcher Jim Owens. The Phillies had an all-star Cuban second baseman, Tony Taylor, and in 1963 Cookie played in only 64 games backing up second and playing outfield. He hit only .221 again, but fielded well, and hit his first major-league home run, a solo shot, on September 17 off of the Mets’ Tracy Stallard at the Polo Grounds.

Rojas worked hard to improve his hitting and quickly developed a reputation as a player who would do whatever the team needed to win. During the 1964 pennant race, manager Gene Mauch used Cookie as a super sub, backing up short and second but also logging a great deal of time in center field when Tony Gonzalez was out, and worked at other positions as well. As Rojas put it, “When I was asked if I could play center field I said yes. When I was asked if I could play third base, I said yes. I never said no.”1

Rojas played in 104 games in 1964, hit a solid .291, and made some key hits that helped the Phillies get a 6½-game lead going into the last two weeks of the season. At the All-Star break Rojas was hitting over .300 as the Phillies surprisingly surged into first place. During a game on July 23 he doubled in the winning run in the top of the tenth to beat the Milwaukee Braves.

A game on July 19 typified how Mauch used Rojas throughout the season. He started in center field, then moved to shortstop and finished the game as the catcher in the Phils’ 4-3 victory over the Reds. During the Phillies’ ten-game losing streak in September, Rojas hit only .200, but several teammates, including shortstop Bobby Wine, hit for a lower average. Rojas was bitterly disappointed that the Phillies’ collapse prevented him from playing in the World Series.

The 1964 season provided Rojas with other unforgettable moments. In an article in Baseball Digest’s November 1979 issue, Rojas called his participation in Jim Bunning’s perfect game “The Game I’ll Never Forget.” Rojas played shortstop during the game and said that the longer the game went the more nervous he was about making a mistake and ruining the game. Rojas made a fine play at shortstop, going to his knees to spear a line drive, but it was clear that he was just as happy as the game went on to not have the ball hit to him.

In 1965 Cookie played everywhere except third base and pitcher, and was the regular second baseman. He appeared in 142 games, batted .303, made his first All-Star team, and received some MVP votes from sportswriters. He was statistically the toughest player to strike out in the National League that year. Rojas had now improved his batting average in each of his major-league seasons. In 1966 his average fell to .268. He played in 156 games.

Even as the Phillies slipped out of the pennant races, Rojas continued to perform. In 1967, he played every position except first, including pitching one inning in the second game of a doubleheader, and joined the small group of major leaguers who played every position during their career. He allowed no runs and never pitched again, so his lifetime ERA remains 0.00. He played in 147 games and hit .259. Mauch liked to bunt, and Cookie led the National League with 16 sacrifice hits. He finished second in double plays by NL second basemen, behind only Bill Mazeroski.

In 1967 Cookie teamed with shortstop Bobby Wine to make, as the reporters called it, “The Plays of Wine and Rojas,” a takeoff of the popular film The Days of Wine and Roses. In 1968 Rojas supported his defensive reputation by leading all NL second basemen in fielding percentage with a .987 figure.

In 1969 the Phillies slipped toward the back of the NL East and Cookie’s batting average slipped to .228, marking the fourth straight year his batting average declined. With hot prospect Denny Doyle coming up through the minor leagues the Phillies included Rojas in a postseason blockbuster trade that sent him, slugger Dick Allen, and pitcher Jerry Johnson to the St. Louis Cardinals for Curt Flood, Tim McCarver, outfielder Byron Browne, and pitcher Joe Hoerner. Curt Flood refused to report and demanded to be made a free agent after the trade. His subsequent suit to overturn the reserve clause made it all the way to the Supreme Court, where the reserve clause was upheld. Yet Flood’s case laid the groundwork for eventual player free agency.

For Rojas, the trade was a personal disaster but ended up providing him with a great opportunity. He said, “I was 31 years old and didn’t fit into their (the Phils) plans. When I got to St. Louis they had Julian Javier and didn’t really need me.”2 In limited action, Rojas hit .106 with few highlights. He did win a game with a tenth-inning pinch-hit single on April 14. On June 13 the Cardinals sent him to the expansion Kansas City Royals for outfielder Fred Rico, another example of the Royals’ trading acumen in their early years that landed them players like Amos Otis and John Mayberry.

The Royals were a young team that benefited from Rojas’s veteran leadership. Given an opportunity to play every day, and reinvigorated by his new environment, Cookie finished the year with a solid .268 average and played steady and sometimes spectacular defense for the young team. He teamed up with shortstop Freddie Patek to form one of the best double-play combinations in baseball. Longtime Royals broadcaster Denny Mathews said of them, “They were the first guys I ever saw work the play where, on a groundball up the middle, the second baseman gets to it, backhands it and flips it to the shortstop with a backhand motion of the glove.”3

Despite his success, Cookie considered retiring after the 1970 season. His wife was ill, and he thought his family needed him. When his wife’s health improved, he returned to the Royals and at the age of 32 had arguably the best season of his career, batting .300, leading AL second basemen in fielding percentage with a .991 mark, and finishing 14th in the MVP voting. He represented the Royals in the All-Star Game four consecutive years, 1971-74. In the 1972 midsummer classic, Cookie’s pinch-hit home run in the eighth inning gave the AL a one-run lead, although they would go on to lose the game in extra innings. It was the first time a foreign-born player hit an All-Star Game homer.

Royals broadcaster Mathews said, “He brought the element of experience, class, and big-league smarts to the team. That really helped the expansion team at the time.”4 The Royals rewarded Cookie, increasing his salary from $30,000 in 1971 to $67,500 in 1975. In 1973 Cookie achieved his career high in RBIs (69) and doubles (29).

Cookie turned 36 in 1976 and started losing playing time to a promising young star, Frank White. In 1976 Rojas batted only 132 times, hitting .242. Although he wanted to play, Cookie understood the Royals’ reasoning. “They had to give Frank White a chance,” he said.5 In Cookie’s final season, 1977, he played even less as White became an All-Star for the Royals. Rojas did achieve his goal of playing in the postseason in 1976 and ‘77, hitting .308 (4-for-13), in part-time play in losses to the New York Yankees in the American League Championship Series. Rojas summed up his playing career like this: “I came in with a reputation of not being able to hit and I developed a reputation as a winning player who would do anything and play anywhere to help you win, who could not only contribute with his bat and glove but with the experience he passed along to the other players. And the more I played, the more determined I became to remain in the game when I retired.”6

Rojas signed with the Cubs ostensibly as a defensive replacement in 1978, but never appeared in a game. After he retired from playing, the Cubs hired him to coach and scout, and as of 2013 he’s been involved in baseball ever since. In the 1980s he moved to the Angels as a coach and advance scout. In 1988 the Angels made him the third Cuban-born manager in baseball history. He didn’t last the season, however. The team fired Rojas with about two weeks remaining in the season and their record at 75-79.

The Angels still valued Cookie’s baseball knowledge, and offered him his former job of advance scout after the season, which he accepted. In 1992 the expansion Florida Marlins hired him as the third-base coach for their inaugural 1993 season. He then became Bobby Valentine’s third-base coach on the Mets from 1997 through 2000, participating in his first World Series. In the 1999 playoffs he got into an argument with umpire Charlie Williams over a ball hit down the left-field line that Williams called foul and Rojas thought was fair. He was suspended for five games for bumping Williams. Bobby Valentine hung Cookie’s jersey in the dugout until he rejoined the club.

Rojas went to the World Series as a coach with the Mets in 2000. The next two seasons he served as bench coach for the Toronto Blue Jays. In 2003 Cookie took the job he still held as of 2013 as a Spanish-language broadcaster, a color commentator for the Florida Marlins. His son Victor was also a broadcaster, for the Anaheim Angels.

In addition to Victor, Cookie, and his wife (the former Candy Rosa Boullon) had three other sons – Octavio Jr., Miguel, and Bobby, and a number of grandchildren.

Rojas is a member of the Philadelphia Phillies, Kansas City Royals, and Cuba’s baseball Hall of Fame, and played the second most games at second base in Royals history (789), after Frank White (2,151). Rojas continued to be a popular and revered figure in the game. In 2012, when Marlins manager Ozzie Guillen made a statement saying he admired Fidel Castro, which upset and alienated some of the Marlins’ Cuban-American fan base and threatened to harm ticket sales, Rojas did his best to repair the damage and stem controversy. As a Cuban, he acknowledged that Guillen’s comments “opened a wound.”7 Then he added some words that probably summed up not only his feelings about Guillen’s remarks, but also how he dealt with many of his own professional disappointments:

“Let’s get over it and play ball.”

Last revised: August 27, 2014

This biography appears in “Kansas City Royals: A Royal Tradition” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bill Nowlin. An earlier version appears in “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin, and “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Bjarkman, Peter, A History of Cuban Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, 2007).

Golenbock, Peter, Amazin’: The Miraculous History of New York’s Most Beloved Baseball Team (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002).

Matthews, Denny, and Matt Fulk, Denny Matthews’ Tales from the Royals Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2006).

Palmer, Pete, and Gary Gillette. The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2004).

Rossi, John P., 1964 Phillies: The Story of Baseball’s Most Memorable Collapse (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, Inc., 2005).

Thorn, John, et. al. Total Baseball (Wilmington, Delaware: Sports Media Publ., 2004).

Westcott, Rich. Phillies Essentials (Chicago: Triumph Books. 2006).

Rojas, Cookie, “The Game I’ll Never Forget,” Baseball Digest, November 1979.

Soderholm-Difatte, Bryan, “Gene Mauch and the Collapse of the 1964 Phillies,” Baseball Research Journal (The Society for American Baseball Research), Fall 2010.

Huffington Post

Los Angeles Times

Miami Herald

Nevada (Missouri) Daily Mail

Philadelphia Inquirer

Markusen, Bruce, Thehardballtimes.com.

Philly.com.

Royalsreview.com: The 100 Greatest Royals of All Time.

Notes

1 Ross Newhan, Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1988 (Rojas interview).

2 Nevada (Missouri) Daily Mail, September 22, 1976.

3 Denny Matthews and Matt Fulk, Denny Matthews’ Tales from the Royals Dugout, 95.

4 Ibid.

5 Nevada Daily Mail, September 22, 1976.

6 Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1988.

7 Huffington Post, April 16, 2012.

Full Name

Octavio Victor Rojas Rivas

Born

March 6, 1939 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.