Hal Keller

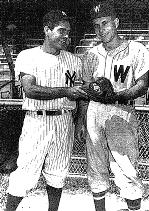

Hal Keller was 12 years old in 1939 when his brother Charlie became a hitting sensation for the New York Yankees. “I was in sixth grade when he played in his first World Series,” Hal remembered 71 years later. “I was proud as a peacock. They were all day games, and the teacher brought a radio in the classroom and we’d listen.”1 As the Yankees swept Cincinnati in four games, Charlie Keller, in his rookie season, batted .438 and hit three home runs, and that performance served notice that the man the press had dubbed King Kong was well on his way to a brilliant major-league career.

Little could Hal have imagined at the time the path his own life would take. If he never reached the level of stardom that his celebrated brother experienced nor even became a household name among fans, still, in a baseball career that stretched over 50 years as a player, manager, farm director, and front-office executive, Keller enjoyed success at every level of the professional game. Indeed, as Keller, then 82 years old, told a reporter in January 2010, “Baseball was good to me, no two ways about it.”

Perhaps it was inevitable that he would be a ballplayer. Born July 7, 1927, on a farm in Middletown, Maryland, a rural community in the western part of the state, Harold Kefauver Keller was the youngest of four children and the third son born to Charles Ernest and Naomi Kefauver Keller. Hal was 11 years younger than Charlie, and by the time Hal began to hone his skills his brother had already left home and was gaining renown in college and the minor leagues. So Hal developed as a player without much input from the future Yankees slugger.

In addition to Charlie and Hal (a sister, Ruth, was the oldest child), another brother, Hugh, two years Charlie’s junior and nine years older than Hal, was also a gifted ballplayer. Hugh was a shortstop, and a cousin, Jack Remsberg, who grew up with the Kellers in Middletown, remembered him as “a great hitter.”2 As Charlie had before him, Hugh starred at the University of Maryland. During World War II Hugh entered the service, and by the time he got out he was too old to pursue a baseball career. (When Hugh was a star in the local Frederick County League, Hal served as a batboy on Hugh’s team. Later, Hugh became a high-school coach and also played semipro baseball.) With older brothers like those, it was only natural that Hal, too, would take an interest in the game.

Growing up on a farm, the brothers of course had plenty of chores to do. Through their daily labors both of Keller’s brothers had developed powerful physiques that formed the foundation of their hitting power, and Hal was no exception; fully grown, the left-handed slugger reached 6-foot-1 and weighed 200 pounds. Unfortunately for the Kellers, during the Depression they lost their farm to foreclosure, so Hal worked instead on the Remsbergs’ neighboring tract, milking cows each evening after school. He also accompanied Jack Remsberg to fairs, where the finest of the cattle were displayed.

Still, there was always time for play. Given the age disparity between Hal and his brothers, their influence on him was minimal, so he was largely on his own when it came to developing fundamentals.

“I learned to play ball in a church parking lot in Middletown,” Keller recalled during a phone conversation with the author in 2010. “However many kids showed up, that’s how many played — even two on a side, if need be, although there were usually three or four. If you hit the ball to the opposite field, you were out. I think that was better than the pressure of Little League.” Later, as his brothers had, Keller attended Middletown High School, where he played second base on the baseball team.

During those years Charlie’s celebrity understandably provided some advantages for his little brother. Charlie often visited home when the Yankees traveled to Washington to play the Senators; Middletown is about 50 miles from Washington. Hal said Charlie never brought any of his teammates to Middletown, but during a series in 1939, his rookie season, 12-year-old Hal attended a game and met Lou Gehrig. Despite having already been diagnosed with his fatal disease Gehrig was still traveling with the team, and Hal was mesmerized by the introduction. The meeting remained as vivid to Hal more than seven decades later as it did the day it took place.

During those years Charlie’s celebrity understandably provided some advantages for his little brother. Charlie often visited home when the Yankees traveled to Washington to play the Senators; Middletown is about 50 miles from Washington. Hal said Charlie never brought any of his teammates to Middletown, but during a series in 1939, his rookie season, 12-year-old Hal attended a game and met Lou Gehrig. Despite having already been diagnosed with his fatal disease Gehrig was still traveling with the team, and Hal was mesmerized by the introduction. The meeting remained as vivid to Hal more than seven decades later as it did the day it took place.

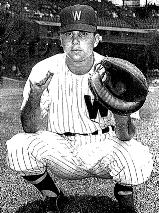

While Charlie Keller became a schoolboy legend at Middletown High School, ten years later circumstances were different for Hal. With the effects of World War II being felt across the nation, gas rationing dictated that teams had to reduce their travel. As a result, Hal remembered, he played in only three or four games throughout his high school career. Nonetheless, his name carried significance. Both Charlie (1934-36) and Hugh (1939-40) had starred at the University of Maryland playing for coach Burton Shipley, and once Hal graduated from high school in 1944, coach Shipley, in Hal’s words, “wanted to see what the next Keller could do.” So the coach secured a $500 scholarship for Hal from Sears Roebuck, got him a job in the dining hall, and the last of the Keller brothers enrolled at the University of Maryland. He played there during the 1945 season, shuttling between catcher and center field.3

That year Keller’s fortunes took a dramatic turn. Early in 1945 coach Shipley, who was a friend of Senators owner Clark Griffith, took Hal to Griffith Stadium for a tryout overseen by Washington’s general manager, Ossie Bluege. Bluege expressed interest in signing him, but Keller told him a baseball career would have to wait, because he was soon to enter the military.

“Soon” turned out to be the following year. Keller received an appointment to the Merchant Marine Cadet School, in San Mateo, California (Charlie had served in the Merchant Marine the previous two years). Hal headed off to become what was the equivalent of a plebe at the Naval Academy. After a year, however, with no opportunity to play baseball, Keller left the school and enlisted in the Army. That year he also married his first wife, Marietta, with whom he eventually produced five children. (Their marriage ended in divorce.)

Throughout 1947 Keller played baseball in the Army. Early in the year he joined the Sixth Infantry Division team as a catcher in South Korea, and that experience, he recalled, “was my real introduction to baseball.” The Sixth won a service title in 1947 and went to Hawaii to play in the FEC tournament, a service championship series among Army teams. “Those teams had older guys,” Keller recalled, some as old as 35, and the Sixth eventually lost. Nonetheless, the 20-year-old had gained invaluable experience, and he returned home eager to begin his professional career.

Keller was discharged from the Army on February 28, 1948. He had agreed to join the Senators in Orlando, Florida, for spring training the following week, but first he returned home to visit his family. He and his wife arranged for veterans housing in Frederick, 10 miles from Middletown. On March 6 Keller reported to training and signed a contract for the 1948 season.

For the next five years Keller remained in the Washington organization and tried to establish himself as a major leaguer. When he broke in, he hadn’t really played a lot of organized baseball; nonetheless the Senators considered Keller, in the words of owner Clark Griffith, perhaps their hottest prospect,4 and they were optimistic about his future. What they were not completely sure of, however, was what position the hot prospect would play. So divided had the Senators had been over Keller’s defensive abilities that it took them two seasons to decide. While he had spent some time at the University of Maryland playing in the outfield, he had been used most often at catcher. Many of the scouts who watched him at College Park considered it his strongest position. But General Manager Bluege, as well as several others in the Senators organization felt strongly that Keller possessed the speed and skills to play the outfield. So as the 1948 season got under way, that’s where he began his professional career.

His first season in pro ball proved only moderately successful. He split time between two teams in Class-B leagues, Charlotte in the TriState League and Hagerstown in the Interstate League, 30 miles from his Frederick home. Playing in both left field and center field, Keller usually batted third or fourth yet often struggled, hitting a combined .258 with a slugging mark of just .354. In spring training in 1949 it came out that during his time in the service Keller’s coaches had altered the stance and swing he had learned at Maryland, and so he had spent 1948 trying to “rearrange himself.” When he finally got his timing and mechanics restored, the Senators got the production they had hoped for, and 1949 turned out to be Keller’s finest season as a ballplayer. Back with the Hagerstown Owls, he batted .322, sixth highest in the league, with a .434 slugging average and 95 RBIs for a last-place team; typically batting fourth, he led the team in almost every offensive category. On defense Keller was shifted to right field, where he played the position, wrote one sportswriter, “like a veteran … pulling down line drives and sky balls that used to drop in for base hits.”5

“Equipped with one of the strongest throwing arms in the league,”6 a newspaper said, Keller “[threw] to third and home from his post in right field as if he was pitching strikes.”7 By the end of the season he was considered “one of the best outfielders in the league.”8 Not surprisingly, when the rosters expanded on September 1, Keller received a callup to the major leagues.

The 22-year-old made his major-league debut on September 13, 1949. Entering as a pinch-hitter for pitcher Joe Haynes in the eighth inning at Griffith Stadium, Keller singled off Randy Gumpert of the Chicago White Sox (“I was leading the league in hitting for about 12 hours,” he laughingly remembered) and moments later he scored the second run of a 3-2 Senators loss. His only other appearances that month were two more pinch-hitting appearances, both unsuccessful.

Keller’s career year at Hagerstown before his call-up wasn’t completely serene. In August he stayed behind when the Owls departed on a road trip. He had a back problem and, a sportswriter reported, “is in Washington undergoing special treatments under the supervision of the Senators’ trainer.”9 As Keller was at the time “highly regarded by Washington’s front office,”10 the article said, the team was “taking no chances with the future of the big boy.”11 As it turned out, the Senators had been less than impressed with Keller’s speed, and decided to make him a catcher. (In anticipation of the move, Keller had played 27 games at the position at Hagerstown.) In a 2010 interview Keller said he had reconciled himself to the move. Still, he felt the Senators had made a big mistake allowing him to “waste” two years in the outfield if they intended to make him a catcher. Still, he went home that winter prepared to compete for a roster spot the following spring. He didn’t make it. Keller never again was more than just a prospect at the major- league level. In retrospect, he said, “I was probably a pretty good Triple-A hitter, nothing more,” even though “I considered that my best asset — hitting.”

But there was to be one more highlight before he was through. Failing to make the Senators out of training camp in 1950, Keller was assigned to Augusta in the Class-A South Atlantic League, where he remained for the entire season, posting solid batting and slugging averages of .296/.427. When the Senators expanded their roster in September, they again recalled Keller and this time he got on the field, appearing in eight games behind the plate. Of his six hits, one was memorable. On September 29, in the top of the eighth inning at Fenway Park, the Senators trailed the Boston Red Sox 6-4 with a runner on base and one out. On the mound for Boston was a 29-year-old rookie right-hander named James Atkins, who was making his major-league debut.12 With three Senators having already homered, manager Bucky Harris sent Keller to the plate as a pinch-hitter, and the 23-year-old promptly homered against Atkins to tie the game, 6-6. (Boston eventually won, 7-6, in the bottom of the ninth.) It was Keller’s only major-league home run.

In 2010 Keller couldn’t remember the name of the pitcher who gave up the home run. However, he recalled with pride one thing quite clearly. After hitting the home run, Keller went behind the plate in the top of the ninth. That inning, when Ted Williams came to bat, Williams turned to Keller and said, “Didn’t that feel good?”

Keller spent all of the 1951 season with Chattanooga in the Double-A South Atlantic League (he never played for Washington that year), and began the 1952 season there as well. In July, when an injury sidelined Washington’s backup catcher, Clyde Kluttz, Keller was recalled to the Senators for what turned out to be the final time, and he saw action in his final 11 major-league games, the last of them on July 28. On August 7 Keller, now out of options, was sold to Toronto in the International League. His five-year Washington career was ended. He played three more seasons in the minors. In the first of them, 1953, Keller finally felt the effects of the back injury he had suffered in 1949, his second year in baseball. “I just couldn’t run anymore,” he recalled. In October 1953, after playing first in Toronto and later in Kansas City, Keller underwent surgery to repair a herniated disk.

In 1954, on loan from Toronto, Keller spent his last full minor-league season playing with the Memphis Chicks and, ironically, it was one of his best (.321 with 15 home runs). Toward the end of the season Toronto needed a catcher and recalled Keller. He got into one game and walked in his only appearance.

The next season, his last as an active player, Keller was playing for Oshawa, Ontario, in an outlaw league, when Toronto summoned him again. “They signed me to help out,” he remembered, “but I was essentially a bullpen catcher.” And with that, his playing career was ended.

It took Keller only a year, however, to set the remainder of his life in motion. In 1948, after his stint in the Army, he had returned to the University of Maryland to renew his education; he enrolled that year in the fall semester and for the next five years earned the equivalent of six semesters’ credits (“I’m very proud of that,” he said) and qualified for a degree in agricultural economics (the same degree as Charlie’s) in January 1953. Also, while still playing Keller had spent his winters substitute-teaching in Frederick County. With his playing career over, Keller became a full-time teacher and the baseball coach at Frederick High School.13 Charlie, too, had settled in Frederick after his career ended, purchased 300 acres of land and begun Yankeeland Farms, where for the remaining 35 years of his life he bred champion trotters and pacers. Both of Charlie’s sons, Charlie Keller III and Donald, attended Frederick High School and were coached by their uncle Hal.

One afternoon Hal’s friend and former teammate, Joe Haynes, who scouted for the Senators, came to Frederick High School to watch Charlie’s sons play, and Hal suggested to Haynes that he wouldn’t mind returning to the game in some capacity. “I wasn’t making much money,” Hal remembered, “and I told Joe if he had a Rookie League job, I wouldn’t mind managing.” Hal hadn’t necessarily had any aspirations to manage; he simply wanted to make more money.

In 1958, Keller became the manager of the Senators Rookie League team in Superior, Nebraska, a town with a population of about 3,000, where, he recalled, “you could shoot a cannon down Main Street and never hit a soul.” The team dressed in a high-school gym, drew a total attendance of 8,953, and finished last in the Nebraska State League with a record of 22-41. Other than as a player, it was the only on-field job Keller ever held in professional baseball.

The following year he took on an even bigger challenge. After the season Keller boldly asked Senators farm director Sherry Robertson for a job, and Robertson offered him the position of assistant farm director. (“I talked myself into two jobs,” Keller told me, referring also to his managerial stint.) Keller held the position for the next two years.

During our interview there was one point about which Keller was adamant. “I want you to highlight this when you write,” he said. “The Griffiths had a reputation for being cheap. They were never cheap. They did everything first class — what they could afford.” In fact, he said, the team took the entire front office, including secretaries, to both Mexico City and Hawaii for the winter meetings.

As Keller began his front-office career, for several years he continued to live in Frederick and commute to Washington. Throughout, he and Charlie remained close. “He was kind of a quiet guy,” Hal said. “He didn’t like people talking too much; he would say someone was ‘popping his bill when he should have been listening.’” They remained close even after Hal later moved 50 miles away, to the Washington suburb of Greenbelt, Maryland.

In his two years as an assistant, Keller learned the ropes of player development. Then, when the “original” Senators moved to Minneapolis after the 1960 season, Keller was named farm director of the expansion Senators team that replaced them. He remained in that position until October 1962.

As farm director Keller assumed broad responsibilities, effectively serving as both director of scouting and player development. Back then, he recalled, “you had all those responsibilities under one hat. Now they have five guys.”

During his first year in the position the Senators spent $300,000 in bonuses and Keller doubled the size of his scouting staff. When the bonus money was cut in half the following year, Keller no longer felt he had the tools to operate successfully. So in October 1962, he left and took a position with the Minnesota Twins as their Eastern scouting supervisor. There, Keller soon fell victim to the hit-or-miss horrors of scouting. In 1964, he traveled to New York to watch a young second baseman play for a team sponsored by a department store. Later, he discussed the prospect with one of his scouts.

“I said I thought [the prospect] would make a pretty good second baseman,” Keller remembered almost 50 years later. “But I questioned whether he could hit.” Eventually, Keller said, “he became a much better hitter than he was a second baseman.” The player was Rod Carew. “So that goes to show how smart you are.” Still, he eventually recommended signing the future Hall of Famer.

After two years with the Twins, in October 1964, at the urging of Washington general manager George Selkirk, Keller returned to the Senators as farm director. At the time Washington had about 130 players in the organization, including 40 at the major-league level, many of whom Keller had brought to the organization during his first go-round, including Eddie Brinkman and John Kennedy, an infielder whose development later allowed the Senators to trade for Frank Howard.

As farm director, Keller recalled, he maintained a simple philosophy. “I always tried to do two things. I tried to place a player high enough that it was challenging, but not too high he couldn’t succeed; and I tried never to send a player down. If he was hitting .200 at Double-A, I’d rather he stayed there and finish at .240, rather than hit .300 at A.

“I never liked to promote them, either. If [a player] was having a good year, I’d rather he finish with a good year and then have him jump a class at the beginning of the next season.”

And there was one final credo Keller adhered to, the one he was most proud of: “I never told a lie to a ballplayer. I always felt that at that stage you’re screwing around with a man’s life.” It was a sentiment that served him well for a very long time.

Within the farm system, decisions about a player were democratic among all minor-league personnel, Keller said, but he always reserved veto power over managers who wanted to place a player too high.

And he continually sought innovative ways to teach. In fact, he may have been a trend-setter. “I think I was the first man to use a radar gun,” he said. Sometime in the early ’70s, Michigan State baseball coach Danny Litwhiler, who used the gun, wrote to each major league team suggesting that they also might benefit from its use. Keller was intrigued, and bought one. Although he and Joe Klein, a former Senators minor leaguer then working in the front office, initially used the gun as a scouting tool, they soon found it had coaching possibilities, and so the radar gun as a teaching tool for Rangers’ prospects was born. Each scout in the organization was given a radar gun.

By January 1979 Keller had been with the organization almost 15 years. When Senators owner Bob Short moved the club in 1972, Keller moved with the team to Arlington, Texas, where the Senators became the Rangers, and retained his position. He had no nostalgia about relocating the franchise, he remembered, saying, “I was being paid, so I didn’t care.” Besides, “I thought Washington was a dead end.”

While in Texas Keller oversaw the drafting of such future major leaguers as Mike Cubbage, Dave Righetti, Roy Smalley, Bill Madlock, and Len Barker, as well as the blossoming of Jeff Burroughs, whom Keller had earlier developed in Washington. Keller was unhappy when new owner Brad Corbett began trading them away (“they wanted to trade Jim Sundberg too,” Keller recalled, “but I wouldn’t let them”), and “I got discouraged.” So when the new Seattle Mariners came along with a job offer, “I took it.”

On January 22, 1979, Keller was named director of player development for the Mariners. He and Mariners President Dan O’Brien had worked together for five years in Texas, and when O’Brien left Texas to head the Mariners, Keller was the first person he considered to run Seattle’s farm system. Keller “has proven his ability to put together a farm system in an expansion franchise setting, one which is currently producing top quality major league players,” O’Brien said. By then more than 50 players whose development Keller had at one time supervised had played in the major leagues.14

Keller retained his post for the next four years. During that time he oversaw the drafting and development of such future Seattle stars as Spike Owen, Harold Reynolds, Phil Bradley, Mark Langston, Bud Black, Darnell Coles, and the 1984 American League Rookie of the Year, Alvin Davis.

A final front-office challenge awaited Keller. In 1983, after the Mariners finished with a dismal record of 60-102, Dan O’Brien, the team president and general manager, was fired, and the 56-year-old Keller was named vice president of baseball operations and general manager. The Mariners won 74 games in each of the next two seasons. But the everyday demands of his new position soon became too great. “I didn’t like being the GM,” Keller recalled in January 2010. “It’s a pressure-packed job. I would have liked it ten years before.” Negotiating contracts “was much tougher with the players than it was in the old days, and I felt the pressure. My blood pressure felt it,” he said. As well, “the game had kind of passed me by.” In July 1985, “I thought it was best for me to retire.”

Keller remained away from the game for three years. By 1989, though, he felt an urge to return and joined the Detroit Tigers as a national cross-checker, evaluating players who had already drawn the attention of other scouts, a job in which “You try to rate the cream of the crop for the draft.” Later, he performed the same scouting function for the California Angels.

In 1998 Keller underwent a heart bypass, and the following year he finally retired for good. During his years in the Mariners’ front office he had resided in the town of Issiquah, outside Seattle. In 1999 he and his second wife, Carol, whom he had married in 1967, moved to Sequim, Washington, near the Olympic Mountains. In addition to five children by his first wife and two stepchildren from Carol’s first marriage, Carol and Hal also had one child together. There were 11 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

A few years after he retired Keller’s right leg was amputated below the knee. In 2010, he said, “I’m not at all active but I have people that call. … I try to keep up with what my acquaintances are doing. You need to. They move around a lot more now than they used to.”

On January 16, 2010, in a ceremony in Los Angeles, Keller received the George Genovese Lifetime Achievement Award from the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation for “long and meritorious service in the world of professional baseball scouting.” Keller, said foundation chairman Dennis Gilbert, was a natural choice to receive the award. “He is a very well thought-of person in the baseball community,” Gilbert said15. It was a just reward for a life well spent. About receiving the award, Keller said, “When you recognize talent, you like to see them develop. That’s the fun part of the business.”

In his last years, Keller’s health markedly declined. In addition to battling the diabetes that had caused the amputation of his foot, he also developed a growth on his vocal cords, which was eventually diagnosed as esophogeal cancer. After enduring chemo and radiation therapies, in May 2012 he was hospitalized due to dehydration brought on by an inability to intake enough liquid. On Thursday, May 31, Keller finally asked to go home to Sequim, Washington, where during the early hours of June 5, 2012, he died peacefully in his sleep.

That afternoon, Keller’s wife, Carol, related to the press, “He told three doctors he had a wonderful life and had done everything he wanted to do. He said he wanted to go home. He said he didn’t want to spend 10 years in a nursing home.”16

It had indeed, been a fantastic life.

On June 30, 2012, a memorial service was held for Keller at the American Legion in Frederick, Maryland. Very few baseball people attended. Among those who did were Keller’s good friend, Joe Klein, and Darnell Coles, one of the featured speakers.

Hal Keller was cremated and his ashes were scattered over his birthplace, his beloved Middletown Valley.

This biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

My sincerest thanks to Hal Keller for personal phone interviews on May 21 and 22, June 4, and August 30, 2010.

My sincerest thanks to Jack Remsberg, Hal Keller’s cousin, for a personal interview at Remsberg’s home, July 2, 2009

E-mail exchanges on May 24 and August 18, 2010, with Randy Adamack, vice president of communications, Seattle Mariners.

Telephone conversation with Carol Keller on July 21, 2012.

Many thanks to Jason Speck, an archivist at the University of Maryland Archives, for information on Keller’s career at the university.

The author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, the Hal Keller player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following newspapers:

News-Post (Frederick, Maryland), Pacific Stars and Stripes,The Sporting News, Oakland Tribune, and www.sportsillustrated.cnn.com, , and http://www.powerset.com/explore/semhtml/Nebraska_State_League

Notes

1 Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Hal Keller were from interviews the author conducted between May 21 and August 30, 2010.

2 Authors interview with Jack Remsberg, conducted July 2, 2009.

3 According to University of Maryland archives, during the later war years (1943-45) Maryland did not field a varsity team. The team was considered ‘informal’, and no varsity letters were awarded during those years. Additionally, the team mostly played local service units and not colleges and universities. No records exist of the 1944 team; however, in 1945 the team went 2-9. Hal was a starter at both catcher and centerfield and routinely hit in the middle of the lineup. On June 2, 1945, Hal faced off against Hugh, who was playing for a team at Ft. Myers, Virginia, and Maryland won, 10-9. Also, as had Charlie, Hal, too, played basketball at Maryland (during the winter of 1944). “I wasn’t a good shooter,” he remembered, “but I was a good rebounder.”

4 “Senators Consider Hal Keller Hot Prospect,” Wisconsin State Journal, March 8, 1948.

5 Dick Kelly, “The Spotlight on Sports,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, May 27, 1949: 14.

6 Ibid

7 Frank Colley, “The Colley-See-Um of Sports,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Morning Herald, April 21, 1949: 22.

8 Dick Kelly, “The Spotlight on Sports,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, September 30, 1949: 14.

9 Dick Kelly, “The Spotlight on Sports,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, August 5, 1949: 12.

10 Ibid

11 Ibid

12 This would be Atkins’ only appearance in 1950. Two years later he appeared in three more games for Boston, including one start, before finishing his career with a 0-1 record and 3.60 ERA in 15 total innings pitched.

13 One of Keller’s players was an outfielder named Don Loun. Impressed by the young man’s strong left arm, Keller switched Loun from the outfield to pitcher. Later, when Keller became Farm Director of the Senators, he drafted Loun for Washington. On September 23, 1964, Loun tossed a complete game shutout against Boston in his major league debut, and he ended his career with two appearances for the Senators, posting a 1-1 record and 2.08 ERA.

14 Among those players were: Bill Madlock, Mike Hargrove, Bump Wills, Toby Harrah, Tom Grieve, Dick Bosman, and Len Barker.

15 “Sequim resident, former Mariners general manager, to receive lifetime achievement award this weekend,” Peninsula Daily News, http://www.peninsuladailynews.com/sports/sports-sequim-resident-former-mariners-general-manager-to-receive-lifetime-achievement-award-this-weekend, accessed February 10, 2018.

16 “Keller remembered as top-notch scout,” Fox Sports, https://www.foxsports.com/mlb/story/hal-keller-obit-baseball-scout-radar-gun-060512, accessed February 10, 2018.

Full Name

Harold Kefauver Keller

Born

July 7, 1927 at Middletown, MD (USA)

Died

June 5, 2012 at Sequim, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.