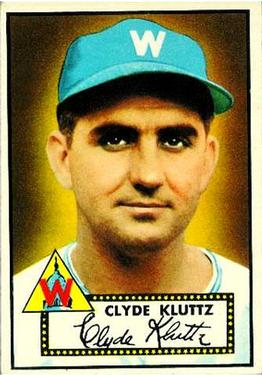

Clyde Kluttz

Clyde Kluttz, a journeyman catcher-turned-scout, convinced Charlie Finley to pay a young North Carolina pitcher named Jimmy Hunter $50,000 to sign with the Athletics in 1964. A decade later, Kluttz, then a super scout with the Yankees, persuaded the All-Star now known as “Catfish” to accept $3.75 million to come to New York in the first of a flood of big free-agent contracts.

Clyde Kluttz, a journeyman catcher-turned-scout, convinced Charlie Finley to pay a young North Carolina pitcher named Jimmy Hunter $50,000 to sign with the Athletics in 1964. A decade later, Kluttz, then a super scout with the Yankees, persuaded the All-Star now known as “Catfish” to accept $3.75 million to come to New York in the first of a flood of big free-agent contracts.

Kluttz earned a World Series ring with the 1946 Cardinals. From 1942 to 1947, he also spent time with the Boston Braves, New York Giants and Pittsburgh Pirates. After two years at AAA, he spent 1951 with the St. Louis Browns and Washington Senators before his big-league career ended after the 1952 season in Washington.

“Clyde was shopped around,” sports columnist Jim Murray wrote in 1975, “usually landing on teams that had whole dugouts of Clyde Kluttzes.”1

In addition to managing in the minors and scouting for the A’s, Kluttz scouted for and was the director of player personnel for the Yankees and Orioles in the years before he died in 1979. He spent his entire adult life working in professional baseball.

Clyde Franklin Kluttz was born in Rockwell, North Carolina, on December 12, 1917.2 His parents were Arthur L. Kluttz, whose family was of German descent, and the former Rosanna Parks. Clyde was the sixth of their seven children. He had three older sisters — Esther, Maggie and Carrie — and two older brothers — George, the oldest of the siblings, and Carl.

Alvin, the youngest of the Kluttz family, also played professionally as a catcher in the Cardinals system and, after seeing combat in World War II, managed in the minors. Alvin was seriously injured in the Battle of the Bulge and was awarded a Bronze Star.3

Clyde spent his youth on the family farm in Rockwell in Rowan County, about 40 miles northeast of Charlotte. He lost the tip of his right thumb in a wheat thresher accident long before he began his baseball career.4 Kluttz had the “parchment skin of a man who had spent many a turn behind the plow,” Furman Bisher wrote in The Sporting News in 1975.5

Clyde’s mother was a homemaker whose children were born over a 17-year span. In the 1930 Census, Arthur Kluttz reported his occupation as the recorder of deeds for Rowan County, aside from farming. By 1940, in his 50s, he was a furniture salesman in a retail store.6

The Piedmont region always had been a hotbed for baseball and produced, among others, Enos Slaughter and Max Lanier long before Catfish Hunter. As Kluttz was growing up, “All we kids thought and talked about was baseball.”7

As a youngster, the strong-armed Kluttz was a pitcher, the position he most often played in high school. By his early teens, he was pitching against much older men in the semipro Piedmont Textile League, in which many North Carolina cotton mills sponsored teams in those days. A right-hand batter, he grew to an even six feet and played at 195 pounds.

It was by chance that he became a catcher. “I never caught a game up to our Textile League playoffs in 1936,” he later recalled. “Our regular catcher … was injured … so I volunteered and caught last two games. And from that time on, I was a catcher.”8

Clyde graduated from Boyden High School in nearby Salisbury, where he also played football. He played baseball for Catawba College in Salisbury for two years. Kluttz was scouted at Catawba by Pat Monahan and signed early in 1938 for the St. Louis Cardinals by Frank Rickey, brother of then-Cardinals General Manager Branch Rickey.9

The Cardinals sent Kluttz to Johnson City in the Class D Appalachian League for the 1938 season, where he hit .318 and made the all-star team. A serious knee injury required surgery and limited him to 79 games, however. The knee required a second operation in 1944 and kept him out of military service as 4-F during the war.

Kluttz was an all-star again in 1939 with Kilgore in the Class C East Texas League, hitting .316. But he tailed off in two stops at Class B in 1940, hitting a combined .248. He thought about quitting. But the woman he married in December 1940 — Elizabeth Wayne Fleming, who went her middle name — persuaded him to give it one more try. Kluttz had met Wayne two years earlier at a basketball tournament in North Carolina.10

Kluttz found himself back at Decatur in the Class B Three-I League to start 1941, but injuries to two catchers at Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League prompted what was expected to be a temporary promotion.

The day Kluttz arrived in California, his three-run homer won the game. “That homer under the circumstances was the biggest thrill of my baseball career,” Kluttz later said.11 Kluttz kept on hitting and playing regularly. When the season ended, he was hitting .336, second best in the league, and was acquired in the minor-league draft by the Boston Braves.

On April 20, 1942, Kluttz made his major-league debut with the Braves in Brooklyn. With Boston down, 7-0, in the sixth, he replaced Ernie Lombardi behind the plate. In the seventh against Kirby Higbe, he grounded to short, but reached on Pee Wee Reese’s throwing error and later scored. Kluttz singled off Higbe in the ninth for his first big-league hit. The Dodgers won, 9-2.

Kluttz appeared in 72 games that season as Lombardi’s backup and hit .267. In 1943 and 1944, he was part of a platoon of three Braves’ catchers. It was more of the same in 1945 until mid-June, when he was traded to the Giants for Joe Medwick and Ewald Pyle.

A hot start with New York — he was hitting .345 as a Giant after a July 4 doubleheader — earned him more playing time. He was in the lineup three out of every four days the rest of the season and finished with a .279 average. This would be the only season in the majors that he would get up more than 300 times.

In 1946, however, he found himself as the Giants’ third-stringer. He told manager Mel Ott that if he wasn’t traded, he’d jump to the outlaw Mexican League.12 On May 1, Kluttz got his wish. With the Giants in St. Louis that morning, Ott told Kluttz to pack because he’d been traded to the Phillies for outfielder Vince DiMaggio. Two hours later, the Phillies called to tell Kluttz he was going to the Cardinals for second baseman Emil Verban. Without leaving town, Kluttz had become a member of the team that would win the NL pennant and the World Series.

Kluttz, who hit .271 overall in 1946, became the Cards’ primary catcher when the team faced a left-hander. Even so, although he was expected to catch Game Two of the World Series against Red Sox lefty Mickey Harris, starter Harry Brecheen asked manager Ed Dyer to let him pitch to Del Rice.13 Brecheen shut out the Red Sox, and Rice had two hits. The series went seven games, but Kluttz didn’t play in any of them.

The day after Christmas, the Cardinals sold Kluttz to Pittsburgh, where in 69 games in 1947, he led NL catchers by throwing out 57.5 percent of runners trying to steal. He also had a career-best fielding percentage of .987. His career average of runners caught stealing was 50.3, which ranks 14th all-time. In what was his best overall offensive season, Kluttz hit .302 in 255 plate appearances. He hit six homers and drove in 42 runs, both career highs. He was finally playing regularly when he suffered a hairline wrist fracture in a home plate collision on June 8 in Philadelphia. He was out for a month. That injury came after he had broken his left thumb in spring training and missed the first two weeks of the season.

Although he played more in 1948, his offense fell off. His .221 average produced a .275 on-base percentage (down from .355) and just 20 RBIs in 297 plate appearances. That was bad enough to get him demoted to Indianapolis.

In a backup role with the American Association team in 1949, he hit .248 in 46 games. But at age 31, he wasn’t ready to call it a career. In late December, the Pirates sold Kluttz to Baltimore in the International League.14 There, he hit .291 in 96 games in 1950 and showed surprising power, with 11 homers. He was named the catcher on the league’s all-star team. He struck out just 16 times in 282 plate appearances. (In the majors, he never fanned more than 22 times in a season.)

The Browns decided that Kluttz had enough left to be the team’s third-string catcher in 1951 and purchased his contract from Baltimore. In early June, however, after just five plate appearances in four games, the Browns waived Kluttz. On June 12, he was picked up by Washington. He appeared in 53 games with the Senators and overall produced career-highs in batting (.313) and OBP (.389).

Kluttz played in 58 games for the 1952 Senators, who finished over .500 at 78-76, the last time the Griffith-era franchise did that. Manager Bucky Harris relied on Kluttz for more than just his catching. “He’s making my job easier…. He’s all business, and I wish I had discovered him 10 years ago,” the veteran skipper said of Kluttz in March 1952.15

Bob Porterfield, who won 22 games, threw nine shutouts and was AL Pitcher of the Year as a Senator in 1953, credited Kluttz “for working with him to perfect his change-up,” Warren Corbett wrote in Porterfield’s SABR bio essay.16 While with Washington, Kluttz sang in a quartet with Porterfield, Tom Ferrick, and Irv Noren.

Kluttz got off to a solid start in 1952 and was hitting .300 after the games of June 1. But he slumped the rest of the way, spending most of July on the disabled list after an appendectomy.17 He finished at .229. Washington released him in October. Still, he was recruited to be part of a group of active players for a postseason barnstorming tour of New York State and Canada.18 Bad weather canceled most of the tour.

About to turn 35, Kluttz signed on as a player-coach with Baltimore, still in the IL, in early December. He appeared in 42 games in 1953, hitting just .192 in what was his last full year as a player. Baltimore, a season away from inheriting the Browns, was the top farm club of the Philadelphia Athletics during its last year as a minor-league city. The link to the A’s paid off for Kluttz, who was hired to manage the Savannah A’s in the South Atlantic League in 1954. He signed on as a player-manager but hurt a knee going after a foul popup in his second game.19 That ended his playing days.

Kluttz guided Savannah to a second-place finish, three games behind Jacksonville, in 1954. He described winning the postseason playoff and pennant as his fondest baseball memory, next to winning the World Series with the Cardinals.20 He managed Savannah to another second-place finish in 1955.

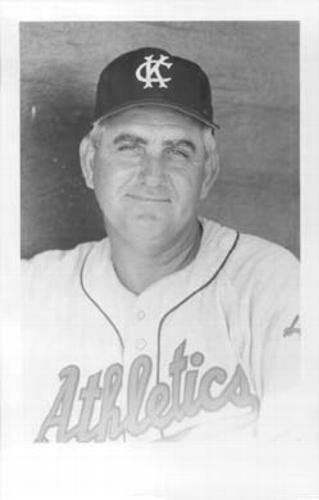

The A’s, now in Kansas City, made him a scout beginning in 1956. He began a close working relationship with Hank Peters that lasted through their time there and later with Baltimore until Kluttz died. Among the players Kluttz signed for the A’s was high schooler Ken Harrelson in 1959.

In 1960, Tommy Giordano, a player he had managed on the 1952 Savannah team, joined Kluttz as a scout for the A’s. He and Giordano would rejoin Peters, both of whom became close allies of their boss, as executives in the Orioles’ front office in the mid-1970s.

Kluttz managed the A’s entry in the Florida Instructional League in the fall of 1961. He got an even better look at some of the other teams’ prospects when he led a league all-star team against the Tigers entry to close the season after the Tigers prospects finished first.

In 1962, 19 years after their first daughter was born, Clyde and Wayne Kluttz had a second daughter, Lisa Dawn.21 She was still in grade school when her sister Donna gave birth to her first child in 1973, making Clyde and Wayne grandparents.

The biggest scouting catch for Kluttz came in 1964 when young Carolina Piedmont neighbor Jimmy Hunter agreed to terms with Finley’s A’s. Kluttz, who by this time had a farm nearby in Salisbury, “took a liking to Jim and made himself a regular visitor at the Hunter home,” Jeff English wrote in his SABR bio essay on Catfish.22

The biggest scouting catch for Kluttz came in 1964 when young Carolina Piedmont neighbor Jimmy Hunter agreed to terms with Finley’s A’s. Kluttz, who by this time had a farm nearby in Salisbury, “took a liking to Jim and made himself a regular visitor at the Hunter home,” Jeff English wrote in his SABR bio essay on Catfish.22

Kluttz kept his faith in Hunter, visiting him after the young pitcher suffered a serious foot injury in a hunting accident before his senior baseball season in high school. “Seeing his face was certainly no surprise,” Hunter wrote in his 1988 autobiography. “He’d almost earned himself a spot in the family portrait, stopping by as he pleased, having dinner, talking to my daddy in the fields and my mom in the kitchen.”23

After Hunter signed, he was sent to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota to have shotgun pellets removed from his right foot. He had pitched well in his high school playoff despite his wounded foot, but the injury had scared off many other scouts. The surgery went well enough that Hunter pitched in the fall Florida Instructional League, where Kluttz was the A’s camp coordinator.

Hunter was among the players Peters and Kluttz signed who would help the Oakland A’s to three World Series after both had moved on. Peters joined Cleveland’s front office. Kluttz left to become a Yankees scout in 1967. In August 1970, he was promoted to field director for player development and in 1974 was put in charge of the Yankees minor-league operations, but mostly he was a super scout. In that role, he was instrumental in getting the Yankees back to the World Series.

The last contract Hunter signed with the Athletics called for him to receive deferred payments in the form of an annuity. In the summer of 1974, as Hunter was leading the A’s to a third straight World Series, Hunter’s attorney repeatedly wrote to Finley demanding compliance with the contract terms. Getting no response, Hunter and his lawyer turned to the Major League Baseball Players Association. The association’s general counsel sent a telegram to Finley on October 4, 1974, declaring that Hunter was entitled to become a free agent.

Under terms of the union contract, the dispute went to arbitration. On December 16, Peter Seitz, an independent arbiter, sided with Marvin Miller, head of the players union, over the counsel for the owners, and declared Hunter a free agent.

Hunter already had alerted Kluttz of the contract dispute and his hope to be able to sign with any team. “I’m going to be declared a free agent,” Hunter told Kluttz in a telephone call about a baseball camp the pitcher was supposed to attend in December. The two men had been hunting buddies over the year since Hunter signed with the A’s. After the call, Kluttz paid a visit to Hunter and his family at their Hertford, North Carolina, home. This was before the arbitration ruling.24

Once Hunter was free to sign anywhere, representatives of every team except the Giants came to talk to Hunter and his legal representatives. Kansas City and San Diego reportedly offered as much as $1 million more than the Yankees, but the relationship Kluttz had with Hunter won out. At a breakfast meeting between the two, Kluttz wrote out the Yankees offer on a napkin. It called for a $100,000 bonus, $150,000 a year for five years, and deferred payments that brought the total to $3.75 million, the largest ever offered to a ballplayer. On New Year’s Eve, Hunter signed the five-year contract, against the advice of his lawyer.25

“I don’t think I would have signed with the Yankees if anybody but Clyde had contacted me,” Hunter told Phil Pepe for The Sporting News in January 1975. “Clyde never lied to me about anything and I knew he wouldn’t now.”26

A year later, after Peters had taken over as Baltimore’s general manager, his first hire was Kluttz as director of player development. “I have always had a high regard for his abilities,” Peter said of the hiring. “I asked [Yankees President] Gabe Paul if I could have permission to talk with Clyde. He gave it to me somewhat reluctantly.”27

“I was happy with the Yankees, and they treated me fine,” Kluttz said. “But I look forward to working with Hank again.”28

Six months after hiring Kluttz, Peters made a multi-player trade with the Yankees that laid the foundation for the Orioles 1979 AL pennant. The trade netted Baltimore pitchers Scott McGregor and Tippy Martinez and catcher Rick Dempsey, key parts of the championship team. Rudy May, also obtained in the deal, was traded in 1977 for reliever Don Stanhouse and outfielder Gary Roenicke, two others who helped the Orioles win. All but Stanhouse also were key players in the World Series winners in 1983. The four veterans Peters gave up in the 1976 trade did nothing to help the Yankees win in 1977 and 1978 and were soon gone.

After Peters was voted Major League Executive of the Year by his peers in November 1979, he gave Kluttz credit for the big trade. “Clyde had worked with the Yankees,” Peters said. “We depended very heavily on his advice.”29

In 1975, Kluttz began to have health problems. He needed surgery to clear an artery. In August 1977, Kluttz suffered a stroke and spent two months recuperating. “My doctor tried to talk me into going on total disability,” Kluttz said in April 1979. “I told him I wouldn’t live six months….This job may kill me, but at least I’ll die happy.”30

Kluttz kept up his busy travel schedule to get a look at Orioles farmhands, but it took a toll. In April 1979, he suffered heart failure and was hospitalized. A day after he assured Hunter, who called to check on Kluttz, that he was doing well, a blood clot caused a fatal heart attack. Kluttz was 61 when he died at home on May 12, 1979.

Rochester, the Orioles’ top farm team, was in the seventh inning of a game against Toledo that night when word reached the dugout that Kluttz had died. “You could see everybody hit the floor when they found out,” said Rochester manager Doc Edwards, who had been hired by Kluttz. “They loved him. He was special.”31

Hunter, Peters, and Edwards were among the many baseball luminaries to attend the funeral for Kluttz. The service was held at Haven Lutheran Church, where he taught Sunday school. He was buried at Rowan Memorial Park in Salisbury.

“The Lord may make me quit,” Kluttz had said months before his death, “but I want to stay in the game until they put dirt on my face.”32

“He helped stabilize the Yankees,” owner George Steinbrenner said on hearing that Kluttz had died. “He’s one of the reasons we’re where we are today.”33 “People like Clyde make baseball the game that it is,” Peters said of his friend. “He had a rare dedication.”34

His soft Southern drawl, accessibility, and easy manner made Kluttz many friends in the press, so it was no surprise that an example of his humor about an exhibition game in April 1954 was widely reported. When the Yankees publicity department wired Kluttz to notify the local press that New York would be pitching Ed Lopat and Allie Reynolds against his Savannah team, Kluttz immediately sent a reply. “Notify the New York press we will pitch the same guys who stopped Milwaukee last Tuesday.”35

Milwaukee had beaten Savannah 27-0 on Tuesday.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb, Chris Rainey, and Phil Williams and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Jim Murray, “Thank Mr. Kluttz for Jim Hunter,” Lebanon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, April 16, 1975: 29.

2 Kluttz listed his birth year as 1918 on his player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame and on his Sporting News contract card.

3Mike London, “A True Ballplayer: In Spite of Injuries, Kluttz Had a Solid Baseball Career,” Salisbury Post, May 29, 2016,salisburypost.com/2016/05/29/kluttz/ and baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/wounded_in_combat/kluttz-alvin.html

4 Chester L. Smith, “The Village Smithy” column, Pittsburgh Press, April 8, 1947: 23.

5 Furman Bisher, “Guiding Hand of Clyde Kluttz,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1975: 2.

6 1930 and 1940 US Census, accessed through familysearch.org

7 Frederick G. Lieb, “Backstop Kluttz Back-Tracks to Cards After Four-Year Detour,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1946: 7.

8 Lieb, “Backstop Kluttz Back-Tracks to Cards After Four-Year Detour.”

[9] Lieb, “Backstop Kluttz Back-Tracks to Cards After Four-Year Detour;” Bob Broeg, “Cards Father-Son Scout Team, The Sporting News, January 30, 1952: 8.

10 March 12, 1942, clipping from an unidentified newspaper in Kluttz’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame research center.

11 Lieb, “Backstop Kluttz Back-Tracks to Cards After Four-Year Detour.”

12 Dan Daniel, “Daniel’s Dope,” New York World-Telegram, May 15, 1946, page unknown, clip in Hall of Fame file.

13 Stan Musial as told to Bob Broeg, “Stan Musial: The Man’s Own Story, Philadelphia Inquirer, May 20, 1964: 51; and “Brecheen 4-Hitter Blanks Bosox, 3-0,” New York Daily News, October 8, 1946: 55.

14 St. Louis Browns news release, September 17, 1950, in his Hall of Fame file.

15 “Kluttz Rides Herd to Make Winner Out of Johnson,” Washington Post, March 16, 1952: C1.

16 Warren Corbett, “Bob Porterfield,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/90794a98

17 Shirley Povich, “In and Out with Catchers,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1952: 9.

18 Povich, “Hal White Leads Barnstormers,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1952: 25.

19 “Aunt Sally’s Gossip,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1954: 24.

20 “Where Are They Now?” Baseball Digest, January 1973: 80.

21 “Where Are They Now?” Baseball Digest

22 Jeff English, “Catfish Hunter,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/a5c18e54

23 Jim “Catfish” Hunter and Armen Keteyian, Catfish: My Life in Baseball (McGraw-Hill, 1988): 29

24 Jim Murray column, “Ruth, Gehrig, DiMag — and Clyde Kluttz,” Des Moines Register, April 10, 1975: 23.

25 Bisher, “Guiding Hand of Clyde Kluttz.”

26 Phil Pepe, “Yankees’ $2.85 million Lands Catfish,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1975: 45.

27 Jim Henneman, “Kluttz Rejoins Peters as Orioles’ Exec,” The Sporting News, January 24, 1976: 50.

28 Henneman, “Kluttz Rejoins Peters as Orioles’ Exec.”

29 Ken Nigro, “Execs Hail Hank Peters as No. 1,” The Sporting News, November 17, 1979: 52.

30 Greg Boeck, “Kluttz Committed to Baseball on the Farm,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 15, 1979: 55.

31 Boeck, “Kluttz Committed to Baseball on the Farm;” “Kluttz’s Death Stuns Wings,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 13, 1979: 50.

32 “A Huge Hole Left in Baseball,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle,” May 13, 1979: 50.

33 “A Huge Hole Left in Baseball.”

34 “A Huge Hole Left in Baseball.”

35 “Wire Exchange Threat or Promise?” New York Herald Tribune, April 3, 1954: 15.

Full Name

Clyde Franklin Kluttz

Born

December 12, 1917 at Rockwell, NC (USA)

Died

May 12, 1979 at Salisbury, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.