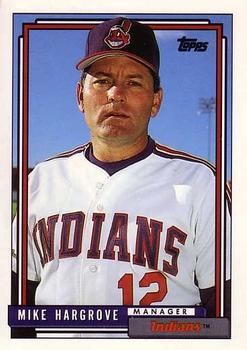

Mike Hargrove

His nickname says it all: The Human Rain Delay. In the years before seemingly every big-league ballplayer stepped out of the box after every pitch to go through a routine of incessant equipment adjusting, Mike Hargrove was an anomaly and drove pitchers, managers, fans, and even broadcasters mad. “With machine-like precision,” wrote Bob Sudyk, “Hargrove approaches the plate, calls time, grabs some dirt, taps at his pants, sleeves, hitches up his waistband, adjusts his hair, taps down his helmet, squeezes his hand deeper into his batting glove, drains all the moisture from his mouth and steps in after raking some dirt in the batter’s box with his cleats.”1 The origins of Hargrove’s routine are innocent. After damaging a nerve at the base of his left thumb as a minor leaguer, in 1973, he devised a sponge doughnut ring to minimize the pain. “It was hard to break in,” Hargrove once explained, “and if I didn’t screw it down my thumb, it would fly off.”2 He claimed his preparation helped him concentrate, but he also admitted candidly, “I wouldn’t like to pitch to myself. … If it also bothers the pitcher, well and good. Maybe he’ll hang a curve.”3

His nickname says it all: The Human Rain Delay. In the years before seemingly every big-league ballplayer stepped out of the box after every pitch to go through a routine of incessant equipment adjusting, Mike Hargrove was an anomaly and drove pitchers, managers, fans, and even broadcasters mad. “With machine-like precision,” wrote Bob Sudyk, “Hargrove approaches the plate, calls time, grabs some dirt, taps at his pants, sleeves, hitches up his waistband, adjusts his hair, taps down his helmet, squeezes his hand deeper into his batting glove, drains all the moisture from his mouth and steps in after raking some dirt in the batter’s box with his cleats.”1 The origins of Hargrove’s routine are innocent. After damaging a nerve at the base of his left thumb as a minor leaguer, in 1973, he devised a sponge doughnut ring to minimize the pain. “It was hard to break in,” Hargrove once explained, “and if I didn’t screw it down my thumb, it would fly off.”2 He claimed his preparation helped him concentrate, but he also admitted candidly, “I wouldn’t like to pitch to myself. … If it also bothers the pitcher, well and good. Maybe he’ll hang a curve.”3

Hargrove hit his fair share of hanging curves. Two years after playing semipro ball, he made an improbable jump to the big leagues and was named AL Rookie of the Year with the Texas Rangers, batting .323 in 1974. The line-drive-hitting first baseman antagonized pitchers, hitting a robust .290 over 12 seasons, the final seven with the Cleveland Indians. Regularly among the league leaders in walks, he finished with a .396 on-base percentage. After his active playing career, he made a seamless transition into coaching. He was a big-league manager for 16 years; the first nine of those were with the Indians, whom he led to five consecutive AL Central crowns and two pennants (1995 and 1997).

Dudley Michael Hargrove was born on October 26, 1949, in Perryton, Texas to Dudley and Rita Ann (Hurter) Hargrove. Like many of the roughly 8,000 residents of the town, located in the northeastern corner of the Texas Panhandle, the elder Hargrove worked in the oil industry, as a pumper; his wife was a nursing-home administrator. The Hargroves provided a sturdy middle-class lifestyle for the four children (Mike, followed by Dennis, Cynthia, and Paula) and instilled in them a relentless work ethic. His father had tryout offers from the Dodgers and Giants in the mid-1940s but couldn’t make either one because of his duties on his family’s farm. Mike played Little League and Babe Ruth baseball and was later coached by his father in American Legion and YMCA ball, but did not take baseball too seriously. A natural athlete, Mike’s passion was football, the king of sports in the state. At Perryton High School he was a defensive back and punter, an accomplished golfer, and an all-conference basketball player, but his school did not field a baseball team. Upon graduation in 1968, Hargrove accepted a basketball scholarship to Northwestern State College (now known as Northwestern Oklahoma State University), in Alva, about 150 miles from Perryton.

At the insistence of his father, Hargrove tried out for the college baseball team. “The first thing I noticed about Michael was how quick his hands were, the way he picked up the ball and threw it,” said coach Cecil Perkins of his initial reaction to the walk-on.4 Hargrove played football and basketball for two years, but his interest gradually shifted to baseball. The stocky 6-foot, 195-pound left-hander was a consistent hitter in college and a capable defensive first baseman but possessed neither the power nor the speed to be considered a hot prospect. He gained additional experience playing semipro ball during the summers. After graduating with a degree in education in 1972, Hargrove moved to Liberal, Kansas, less than 50 miles north of Perryton, where he worked in a meat-packing plant and played semipro ball for the Bee Jays. “I planned to become a high-school coach,” he once said, but those plans were derailed when the Texas Rangers selected him in the 25th round of the draft that June.5

Hargrove’s rise from semipro ball to AL Rookie of the Year in just over two years is as unlikely as it is surprising. After batting just .267 and slugging .350 in his first year of professional baseball, with the Geneva (New York) Senators in the short-season Class A New York-Pennsylvania League in 1972, Hargrove was assigned to the Single-A Gastonia (North Carolina) Rangers in the Western Carolinas League. Among the oldest players on the squad, Hargrove enjoyed a season-long surge and was named league MVP by pacing the circuit in hitting (.351), hits (160), doubles (35), and slugging (.542).

Hargrove’s numbers naturally caught the attention of the Rangers’ brass, who sent him to the Florida Instructional League in the fall of 1973. While there, he was heavily scouted by Billy Martin, who had taken over as the Rangers’ pilot in the last month of the season. Martin liked Hargrove’s compact body and natural swing, was impressed by his hustle, and ultimately invited the prospect to spring training in 1974.

The Rangers were coming off a horrible season in 1973 (57-105) in which they had ranked dead last in runs scored. Martin was in the process of rebuilding the team in his likeness — hard-working, scrappy ballplayers whose commitment to win and playing hard trumped any personal gains. That description fit Hargrove perfectly. Beat writer Merle Heryford reported that Hargrove was widely expected to be sent to Triple-A at best.6 “I’ll never forget how shocked he was when I told him he made the team,” said Martin. “I think he made me repeat it several times.”7 The 24-year-old rookie, described as having the “rugged good looks of a West Texas Brahma bull rider,” made an immediate impact and established himself as the club’s most consistent hitter.8 He saw most of his action against right-handed pitchers. Platooning with Jim Spencer at first base and serving as a designated hitter, Hargrove got off to a fast start, going 13-for-32 (.406) in his first three weeks in the big leagues as the Rangers unexpectedly held down first place at the end of April. “You watch him hit, then you talk to him, and you forget he’s a rookie,” said Martin of his prized Texan. “He’s mature and he’s got all the tools, including the right kind of head.”9 While the Rangers were the surprise of baseball, finishing in second place (84-76), Hargrove collected 134 hits, good for a .323 average (which would have ranked second had he had enough at-bats to qualify for the title). “I don’t consider myself a power hitter or pronounced pull hitter,” said Hargrove, who tallied just 4 homers and 18 doubles. “My best hitting is in right center, but I try to go with the pitch.”10

Hargrove began his sophomore season platooning again with Spencer at first base. Recognizing that he needed his most consistent hitter in the lineup every day, Martin switched Hargrove in mid-May to left field, a position he had never played save for a few games the previous year. Hargrove understandably struggled and never felt at home. “I’ll admit I never counted on being an outfielder,” he said.11 A streaky hitter, Hargrove batted .432 (51-for-118) over a 34-game stretch from May 10 to June 20 to raise his average to .365 while the Rangers fought to play .500 ball. Named to his first and only All-Star Game, Hargrove pinch-hit and popped out in his only appearance in the AL’s 6-3 loss. [The AP reported that residents of Perryton cast 96,000 votes in an effort to get their hometown hero selected to the game.12] With the Rangers failing to live up to expectations, Martin was replaced by Frank Lucchesi on July 21. The former Philadelphia Phillies skipper righted the ship, leading the club to a 35-32 record, but Hargrove entered a prolonged slump, batting just .229 from July 28 through September 18, and saw his average dip under .300 before a late-season surge pushed his average to .303, easily the best mark on the club. He pounded righties for a .329 clip but struggled against lefties (.212).

In 1976 Lucchesi moved Hargrove back to first base, where he was once again the Rangers most consistent hitter, leading the fourth-place club in average (.287), runs (80), and hits (155). He led the AL with 97 walks and finished second with a .397 on-base percentage. In the field, however, the laid-back Texan had a season evoking memories of Dick “Dr. Strangeglove” Stuart. Hargrove committed 21 errors, the most by an AL first baseman since Stuart’s 24 in 1964. “I get sick every time I think about it,” a disappointed Hargrove said after the season.13

“We almost have to be better,” Hargrove told Rangers beat writer Randy Galloway as he headed to spring training in 1977. “Our consolation is that we can’t be any worse than we were in July and August last season (20-41).”14 The season reached its nadir after an ugly incident on May 28. Disgruntled second baseman Lenny Randle, who had lost his job to Bump Wills, attacked Lucchesi, knocking him out. The brouhaha resulted from Lucchesi’s incendiary comments just days earlier, “I’m tired of these punks saying play me or trade me. Anyone who makes $80,000 a year and gripes and moans all spring is not going to get a tear out of me.”15 The fight led to Randle’s suspension for 30 days (and ultimate trade) and to Lucchesi’s dismissal. With the team floundering (34-35) in fifth place, but only 5½ games off the lead, Billy Hunter took over as the skipper. After hitting primarily third in 1976, Hargrove batted in every position in the chaotic campaign before Hunter made an unusual decision. “Let’s just say that I’m not a classic example of what most people expect out of the guy who bats first in the order,” said the slow-footed Hargrove.16 Almost exclusively leading off for the rest of the season, Hargrove batted .308 with a .440 on-base percentage in the final 74 games. Even more surprising was his sudden power surge; he belted 16 home runs in just 260 at-bats. Hargrove’s also improved his glove work dramatically, finishing fifth among first sackers in fielding percentage and becoming a Gold Glove candidate. Texas responded to Hunter, winning 60 of 93 games to finish in second place with a franchise-record 94 wins. “Grover,” as Hargrove’s teammates called him, led the club in hitting (.305), runs (98), hits (160), and on-base percentage (.420).

On paper the 1978 Rangers seemed like one of the best teams in baseball. They had acquired two All-Stars, left fielder Al Oliver and DH Richie Zisk, in the offseason, and Bobby Bonds in a mid-May trade; they had arguably the best defensive catcher in the league (Jim Sundberg), one of the best third basemen (All-Star Toby Harrah), and Hargrove. Widely expected to capture its first division crown, Texas unexpectedly struggled to score runs and was under .500 as late as mid-September before a season-ending surge (15-2) provided window dressing to what beat writer Randy Galloway called a “bad season.”17 Hargrove was mired in a season-long slump, batting just .251, though he led the AL with 107 free passes. A disappointing season was made worse when he injured his left ankle jumping back to first base to avoid a pickoff throw by Oakland’s Matt Keough on September 16. He was carried off the field and missed the final two weeks save for one pinch-hitting appearance.

Even before the season ended, trade rumors swirled around Hargrove, whom The Sporting News called “one of the most popular players ever to wear a Rangers uniform.”18 On October 25, 1978, the financially strapped Rangers sent Hargrove to the San Diego Padres in a multiplayer and cash deal. Hargrove reacted bitterly to the trade: “There are some real (bleeps) on this team. Not a lot of them, but three of four of those ‘hooray for me, the heck with you guys .’ ”19 Al Oliver saw Hargrove as the glue that kept the team together. “This team is going to miss [him] next season. Mike has the same qualities of a Bob Moose and Roberto Clemente,” he said, comparing Hargrove to his Pirates teammates, both of whom died tragically.20

The contact-hitting Hargrove seemed ideally suited for the expanse of San Diego Stadium, but he hit rock bottom in his move to the NL. He batted a hard-to-fathom .192 and lost his starting job. “I didn’t go to San Diego with the best attitude in the world,” said Hargrove. “I went there with a lot of misgiving.”21

In what proved to be one of the more lopsided trades in baseball history, the Padres sent Hargrove to the Cleveland Indians on June 14, 1979, for utilityman Paul Dade. While Dade made only 375 more at-bats and was released after the 1980 season, Hargrove resurrected his career and remained with the organization for the next 20 years as a player, coach, and manager.

The Indians’ acquisition of Hargrove initially seemed like a bad move. With first base occupied by slugger Andre Thornton, Hargrove was moved to left field, where the transplanted Texan continued his batting woes (9-for-52, .173). He turned to coaches Dave Duncan and Joe Nossek for help. “They noted I wasn’t setting up the same way as (1976 and 1977),” said Hargrove. “[So] I lowered my bat and opened my stance slightly and I could wait longer on the pitch.” With his new stance and primarily leading off, “Grover” hit at a .353 clip with a .463 on-base percentage from July 6 through the end of the season for the sixth-place club (81-80). “A good hitter has to be tough mentally, and Mike is a tough, tough kid,” said skipper Dave Garcia, who took over on July 23 and led the Indians to a 38-28 record. “He fights the pitchers. He battles to win. You never hear him complain.”22

Described by Cleveland sportswriter Bob Sudyk as “the possessor of one of the sweetest swings in the game,” Hargrove put together a career-best 23-game hitting streak (32-for-84, .381, .500 OBP) early in the 1980 season. Since the offensive explosion throughout baseball beginning in 1977, teams had increasingly relied on the long ball for success; however, the Indians seemed out of place, ranking last in the AL in home runs (89). Hargrove’s 11 round-trippers tied for second on the club, trailing only rookie Joe Charboneau’s 23. Remarkably, the club finished with a 79-81 record despite the worst pitching staff in baseball (4.68 ERA). Dubbed “The Incredible Twitching Machine,” the 30-year-old Hargrove batted .304, set a new team record with 111 walks, and drove in a career-high 85 runs.23

Hargrove was an “old school” player before there was an old school. He wasn’t flashy, lacked power and the physical attributes of first basemen like Eddie Murray or Cecil Cooper, avoided the spotlight, and rarely criticized publicly his teammates or coaching staff. “The paycheck is anything but Mike’s first consideration,” Nossek once said of the Indians’ acknowledged team leader. “He’s gonna play the game no matter what kind of money he makes. I think he’s one of the big reasons why this club has grown over the years. Not so much because of what he says but by the example he sets.”24 In a poll of players and media, The Sporting News named Hargrove to the All-Hustle team in 1980, and the Cleveland chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America selected him as Man of the Year in 1980 and 1981.

In the strike-shortened season of 1981, Hargrove was one of the few bright spots for the Indians, who finished in sixth place for the fourth of five consecutive seasons. A paragon of consistency, Hargrove batted a team-high .317 and led the AL with a .424 OBP. In interviews after his playing career, he often mentioned playing in right-hander Len Barker’s perfect game against the Toronto Blue Jays on May 15 as “probably the highlight of my career.”25

A remarkably healthy player during his big-league career, Hargrove matched his career high by playing in 160 games in 1982. His batting average fell to .271, though the left-hander drew 101 walks for the sixth-place Indians. His final three years with Cleveland (1983-1985) marked one of the low points in the franchise’s history, as the club finished last in attendance each season while fielding horrible teams. Hargrove, entering his mid-30s, saw his playing time gradually reduced, and was platooned in ’84 and ’85 as Cleveland went to a pronounced youth movement.

Granted free agency after the 1985 season, Hargrove wanted to continue playing but went unsigned. “I talked to some ballclubs and there was some interest and all of a sudden there was no interest at all,” he said. “Since then, with the collusion being proved, I think that was just as much as anything.”26 After batting just a combined .275 and slugging .343 in the previous two seasons, he had a brief tryout with the Oakland A’s as a non-roster invitee during spring training in 1986. His release signaled the end of a 12-year playing career. The classic contact hitter collected 1,614 hits in 1,666 games, belted 80 home runs, and drove in 686 runs. His on-base percentage (.396) was higher than his slugging percentage (.391), an oddity for first basemen in the post-Deadball Era. He wore out Gaylord Perry (18-for-35, .514), Dick Tidrow (12-for-24, .500), and Wilbur Wood (9-for-18, .500) and had troubles with Dave Righetti (1-for-18, .056), Dick Bosman (1-for-15, .067), and Mike Flanagan (3-for-38, .079).

Given his attention to detail, his cerebral and selfless approach to the game, and his leadership skills, Hargrove seemed destined to become a coach. His 21-year career in coaching began in 1986 when Cleveland named him hitting instructor for the Batavia Trojans of the Class A (short season) New York-Pennsylvania League. A rising star in the organization, Hargrove quickly moved up the ladder. He piloted three different teams in as many years from 1987 to 1989 and was twice named manager of the year (with the Kinston Indians of the High-A Carolinas League and with the Triple-A Colorado Sky Sox of the Pacific Coast League). “As a coach and manager you’ve got 23 or 24 guys all wanting your time,” said Hargrove about his learning curve. “So your time is a lot less yours than as a player. That took a lot of adjusting to.”27

Hargrove was back in a big-league uniform in 1990 when he joined the Indians staff as first-base coach. The following season he replaced skipper John McNamara after a dreadful start (25-52), thus inaugurating his nine-year tenure as the Tribe’s manager. The easy-going Hargrove had an ideal temperament for a manager. In an interview with Bonnie DeSimone of the Cleveland Plain Dealer he explained that he learned one of his guiding principles from his college basketball coach, Roy Pennington, who “almost never chewed a player right after a mistake but waited until the emotion of the moment had passed and quietly made a correction.”28

“I’ve tried to take a little bit from every manager that I’ve been around and seen what I’ve thought he’s done well and what I’ve thought he didn’t do well and try to incorporate that into the way I treat my players and the way I run my ballclub,” said Hargrove.29 He cited Billy Martin as a great tactician and Dave Garcia as the best people-person. Players respected Hargrove for his candor, compassion, and patience. “They know they’ll get a truthful answer even if it is not the one they want,” said Indians coach Jeff Newman.”30

Hargrove’s first three full seasons (1992-1994) as Indians manager were marked by frustration, tragedy, and an eye toward a promising future. After two consecutive 76-86 records, the Indians were enjoying their best season in four decades since the days of Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, Mike Garcia, and Herb Score. In second place (66-47) but just one game behind the Chicago White Sox, the Indians saw dreams of their first postseason berth since 1954 dashed by the baseball strike which began on August 12, 1994, and ultimately forced the cancellation of the playoffs. A year earlier, Hargrove consoled his players after pitchers Steve Olin and Tim Crews were killed in a boating accident during spring training.

Hargrove guided the Indians to five consecutive AL Central crowns from 1995 to 1999, thus ending the club’s 41-year playoff drought. Favored to win the World Series in 1995 after barreling through the shortened regular season (100-44), the Indians lost the fall classic in six games to the Atlanta Braves. Two years later, the Indians were two outs away from their first title since 1948 when the Florida Marlins broke the hearts of Cleveland fans by tying Game Seven in the ninth inning, 2-2, and then winning in the 11th. Hargrove was never known as a tactician and was often criticized for his handling of relievers and the way some players seemed ill-prepared or even lackadaisical on the field. Blessed with sluggers, speedsters, and superstars, Hargrove got the most of his players while dealing with a cast of diverse characters, from the surly Albert Belle, whose contempt for the media and even fans was well documented; Manny Ramirez, whose sometimes bizarre on-the-field indifference helped engender his moniker, “Manny Being Manny”; to switch-hitter Eddie Murray, whom the Chicago Tribune called “the most churlish player ever.”31 The Indians’ success corresponded to their departure from cavernous Cleveland Municipal Stadium, which seated approximately 78,000 for baseball games, and move into fan-friendly Jacobs Field (later renamed Progressive Field) in 1994. The Tribe set a big-league record by selling out 455 consecutive games, from June 12, 1995, to April 4, 2001. Hargrove was fired in 1999 after the Indians squandered a two-games-to-none lead against the wild-card Boston Red Sox in the Division Series.

Hargrove’s experiences as a winner in a talent-laden Cleveland organization sharply contrasted with his four-year stint with the Baltimore Orioles (2000 to 2003). He guided the weak-hitting, pitching-challenged club to four consecutive losing seasons and four fourth-place finishes in the competitive AL East.

Hargrove took over the Seattle Mariners in 2005 and guided them to consecutive fourth-place finishes. With the club in second place, riding an eight-game winning streak, and playing their best baseball in four years, Hargrove unexpectedly resigned on July 1, 2007. “It was not a knee-jerk reaction,” he said. “It was something I turned over 15,000 ways.”32 Almost immediately speculation arose that he was forced out because of his increasingly toxic relationship with the team’s star, Ichiro Suzuki. “[Hargrove] never truly explained himself — to his bosses, players, fans or himself,” wrote the Seattle Times.33

Hargrove never donned a big-league uniform again as manager or coach. In 16 seasons as skipper, he amassed a record of 1,188-1,173 (.503).

In an interview with Linda Feagler of Cleveland Magazine.com, Hargrove said that he had lived in at least 23 cities in 13 states and had moved at least 100 times throughout his 35 years in professional baseball. The one constant, however, was his wife, Sharon. “No matter what we did or where we went, we did it together,” said Hargrove. “Sharon and I emphasized that our home was a safe haven and that family mattered above anything else.”34 High-school sweethearts, Mike and Sharon married at ages 20 and 19 respectively, in 1970, and raised five children, Kim, Missy, Shelly, Pam, and Andy. A big, 250-pound first baseman, Andy was drafted by the Seattle Mariners in the 47th round of the 2005 draft and spent three years in the Mariners organization.

Hargrove never forgot his roots, never let success go to his head, or let the millions of dollars he earned in baseball change him. “[He’s] a hometown boy,” said his father.35 After resigning from the Mariners, Hargrove’s path came full circle when he returned to Liberal, Kansas, to manage the semipro Bee Jays in the summers of 2008 and 2009. He also remained close to his alma mater. In 1992 Northwestern Oklahoma State University inducted him into its Hall of Fame, and in 2007 the school honored him on Mike Hargrove Day by retiring his number 30. He was inducted into the National Association of Intercollegiate Sports (NAIA) Hall of Fame in 1999.

Hargrove’s ties to the Indians also remained strong. His success as a player and especially as manager of the Tribe received more critical acclaim after he retired. The club inducted him into its Hall of Fame in 2008; five years later he was inducted into the Cleveland Sports Hall of Fame. He returned to the Indians in 2011 as a special adviser and was a regular presence at spring training through 2014, and also occasionally broadcast games.

As of 2018 the Hargroves reside in the Cleveland area.

Last revised: January 10, 2019

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Notes

1 Bob Sudyk, “Pokey Hargrove Streaks to Hot Start For Tribe”, The Sporting News, May 31, 1980: 33.

2 Gary Herron, “‘The Human Rain Delay.’ Former first sacker Mike Hargrove interviewed,” Sports Collectors Digest, June 22, 1990: 130.

3 Hal Lebovitz, “Can the Tribe keep Hargrove,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 26, 1979: III, 2.

4 Bob Colon, “Time’s Up! Hargrove Is the First,” Newsok.com, July 9, 1991. newsok.com/times-up-hargrove-is-the-first/article/2362281.

5 Dan Coughlin, “The Hargrove Mystery,” Cleveland Plain Dealer. [1979; undated article in player’s Hall of Fame file

6 Merle Heryford, “Sizzling Hargrove Confirms Billy’s Early Sizeup”, The Sporting News, July 20, 1974: 18.

7 Associated Press, “Mike Hargrove: Ranger rookie just a natural,” The Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), June 28, 1974: 19.

8 Ibid.

9 Randy Galloway, “Huge Leap by Top Rookie Hargrove”, The Sporting News, November 16, 1974: 46.

10 Heryford, The Sporting News, July 20, 1974: 18.

11 Merle Heryford, “Soph Jinx Merely Myth to Hot-Hitting Hargrove”, The Sporting News, October 18, 1975: 33.

12 Associated Press, “8,000 Residents of Home Town Cast 96,000 Votes for Ranger Hargrove,” Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, July 3, 1975: 17.

13 Randy Galloway, “Hargrove Looks For Different Year”, The Sporting News, February 12, 1977: 38.

14 Randy Galloway, “Hargrove Looks For Different Year”, The Sporting News, February 12, 1977: 39.

15 Jeff Merron, “Put up your dukes,” ESPN.com. espn.go.com/page2/s/list/basebrawl.html.

16 Randy Galloway, “Sizzling Sundberg, Hargrove Fuel Ranger Surge”, The Sporting News, September 3, 1977: 5.

17 Randy Galloway, “A Bad Season Already Over For Hargrove”, The Sporting News, October 7, 1978: 28.

18 Randy Galloway, “Rangers, Short of Funds, Decide to Gamble”, The Sporting News, November 11, 1978: 47.

19 Ibid.

20 Randy Galloway, “Ranger Revolving-Door Policy Ticks Off Oliver”, The Sporting News, December 2, 1978: 51.

21 Merron.

22 Lebovitz.

23 Merron.

24 Milton Richman (United Press International), “Neither side wants strike,” Ukiah (California) Daily Journal, May 26, 1981: 4.

25 Merron.

26 Merron.

27 Merron.

28 Bonnie DeSimone, “Affair of the heart,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 1, 1995: 20-D.

29 Merron.

30 DeSimone, 21-D.

31 Dan McGrath, “Stuff The Ballot Box,” Chicago Tribune, January 3, 1999.

32 Larry Stone, “Mariners manager Hargrove resigns,” Seattle Times, July 1, 2007.

33 Art Thiel, “Resignation is inexplicable, even for Hargrove,” Seattle Times, July 1, 2007.

34 Linda Feagler, “A New Ballgame,” Cleveland Magazine.com: clevelandmagazine.com/ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=E73ABD6180B44874871A91F6BA5C249C&nm=&type=Publishing&mod=Publications%3A%3AArticle&mid=1578600D80804596A222593669321019&tier=4&id=09B4813C341044E991A7C06DFD943494.

35 Joe Christiansen, “Old Indian guide hasn’t lost his way,” Baltimore Sun, March 19, 2002.

Full Name

Dudley Michael Hargrove

Born

October 26, 1949 at Perryton, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.