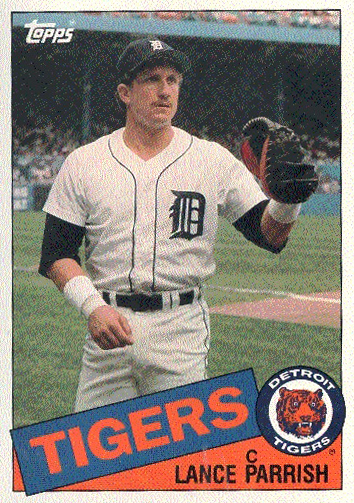

Lance Parrish

A potential championship baseball team should possess both a strong cleanup hitter and catcher to provide stability for the long season. One player left his mark on the 1984 Detroit Tigers by demonstrating to the blue-collar Detroit faithful that he had the strength and versatility to put on the so-called tools of ignorance and swing a powerful bat. It was appropriate that in a city with a history of making fine automobiles, Lance Parrish was nicknamed Big Wheel for keeping the team going on a daily basis during the long summers in Detroit.

A potential championship baseball team should possess both a strong cleanup hitter and catcher to provide stability for the long season. One player left his mark on the 1984 Detroit Tigers by demonstrating to the blue-collar Detroit faithful that he had the strength and versatility to put on the so-called tools of ignorance and swing a powerful bat. It was appropriate that in a city with a history of making fine automobiles, Lance Parrish was nicknamed Big Wheel for keeping the team going on a daily basis during the long summers in Detroit.

Parrish’s prowess on the baseball field earned him appearances in eight All-Star Games. Several questions about Parrish were often raised for most of his 1,988-game major-league career. Baseball officials and managers — including his own, Sparky Anderson — were skeptical of players who frequently did weightlifting, fearing it might hurt their flexibility. Other issues that seemed to be raised, especially in the middle of Parrish’s career were about his salary, major-league baseball collusion, and his back. Could the Big Wheel’s back withstand the everyday pounding that a catcher has to endure? Parrish answered many of these questions as he caught for seven teams during his 19-season career.

Parrish’s hitting and fielding skills earned him three Gold Glove awards and six Silver Slugger awards. Many fans remember the spectacular long-term keystone combination of Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker and the flair for the dramatic of Kirk Gibson. But Parrish had the steady hand that may have flown under the radar at times.

In the fifth game of the 1984 World Series, Gibson’s thrilling three-run homer in the dramatic eighth inning off the San Diego Padres’ Rich “Goose” Gossage will never be forgotten. In the inning before, crafty lefty Craig Lefferts had struck out Gibson. The Tigers were nursing a one-run lead, and Padres manager Dick Williams replaced Lefferts with the future Hall of Famer Gossage to face Parrish. The Big Wheel hit a solo, laser-like homer into the left-field seats to give the Tigers and their bullpen some breathing room with a brief two-run lead. Even though Gibson’s was the signature home run of the series, Parrish helped the Tigers prevail over the Padres with his critical blast.

Former Tigers catcher and Seattle Mariners and Arizona Diamondbacks manager Bob Melvin was impressed by Parrish as he developed in the Detroit system. “I learned a lot from him coming up,” Melvin said. “Lance was supposedly an offensive guy, but they called him the Big Wheel because he drove that train. He was very in tune with the pitchers and was very serious about what he did behind the plate. He was as good an all-around catcher as anyone that I have been around.”

Lance Michael Parrish was born on June 15, 1956, in Clairton, Pennsylvania. His father was a deputy sheriff. The family moved to California from the western Pennsylvania coal country when Lance was 6. As a child, Lance was a fan of Roberto Clemente and Johnny Bench. He attended Walnut High school in Diamond Bar, California, and had the distinction of briefly being a bodyguard for pop-music icon Tina Turner.

Around the time Parrish was in high school, many of the veteran Tigers who had led Detroit to success in 1968 and 1972 were retiring or moving on to other teams. General Manager Jim Campbellecided the Tigers should devote more effort to scouting and drafting young players. He promoted Bill Lajoie to the position of scouting director. Lajoie was responsible for the 1974 draft, and drafted three future Tigers, including Parrish. The Tigers needed a catcher to replace Bill Freehan, and they were disappointed that they had missed out on Gary Carter in a previous draft. Jack Deutsch, a Tigers scout, had spotted Parrish in high school playing third base because he had injured his finger during his senior year.

Parrish had a scholarship offer to play football at UCLA. He demonstrated his baseball skills to the San Diego Padres, the Philadelphia Phillies, the Cincinnati Reds, and the California Angels. The Angels had put Parrish through a workout that tested his offensive and defensive abilities. On draft day in June 1974 Parrish anticipated that he was going to be picked by his hometown Angels as the 10th overall pick. He was surprised when his high school coach informed him that he had been drafted by the Tigers in the first round; the Angels had passed on him and taken shortstop Mike Miley. Detroit was foreign to his Southern California upbringing. Parrish was disappointed and confused about playing for a team and a manager, Ralph Houk, he knew nothing about.

The Tigers introduced Parrish to professional baseball at Bristol (Virginia) in the Rookie-level Appalachian League as a third baseman and outfielder. The Bristol Tigers finished 52-17, good for first in the circuit’s North Division. Parrish hit .213 with 11 homers in 68 games and made 20 errors. His manager was Joe Lewis, and he played alongside future Tigers Mark Fidrych, Bob Sykes, and Tim Corcoran. In 1975 Parrish returned to catching at Lakeland in the Florida State League (Class A). The Tigers tried to convert him into a switch-hitter during this season. The experiment did not work and was dropped at the end of the year. Parrish hit .220 with five homers and 15 doubles.

In 1976 Parrish was promoted to Montgomery in the Double-A Southern League. Les Moss was the skipper, and Parrish had the opportunity to play with future Tigers Alan Trammell, Steve Kemp, Tom Brookens, Jack Morris, and Dave Rozema. The Rebels won the West Division and defeated Orlando for the Southern League championship, three games to one. This was the second of three straight Southern League championships for Montgomery. Parrish’s batting average was still low (.221), but he increased his home run output to 14.

The Tigers promoted the 21-year-old Parrish to Triple-A Evansville, his third consecutive step up. It was the second year that Parrish played under Moss. Parrish improved as he led the team with 25 homers and 90 RBIs. He achieved his best average in the minors with a .279 mark. Moss touted Parrish as the next Johnny Bench. For his part, Parrish insisted that the comparisons with Bench did not bother him. “I modeled my catching after him as a teenager,” he said. As Bench did, Parrish caught the ball with one hand, keeping his throwing hand behind his right leg.

Parrish’s play at Evansville earned him a promotion to the Tigers in the traditional September call-up. On September 5, 1977, he made his major-league debut. There were 22,062 on hand to see the Tigers for the second game of a doubleheader. They faced Rudy May and the Baltimore Orioles at Tiger Stadium, and Parrish started at catcher, batting fifth. Parrish’s first plate appearance ended with a groundout to second base. Batting fifth in the lineup, he had four plate appearances and showed some patience as he walked twice. Two days later, Parrish made his second appearance, in another doubleheader against the Orioles — and made it a game to remember with his first big-league single, double, and home run. He singled in the third inning off Ross Grimsley, hit a bases-loaded double off Earl Stephenson in the fourth and homered in the sixth inning off Stephenson, finishing with four RBIs. On September 9, Parrish started the second game of a doubleheader against the Red Sox. This game featured the debut of Lou Whitaker and Alan Trammell, who continued to play with Parrish through 1986. Parrish finished his season by going 9-for-46 (.196) with three homers and seven RBIs.

Before the 1978 season Parrish toured Michigan with Ron LeFlore, Mark Fidrych, Jason Thompson, Dave Rozema, Steve Kemp, and Milt Wilcox in the annual late-January press tour to promote interest in the Tigers. In spring training the Tigers anticipated that he would back up Milt May at catcher, but Ralph Houk made a critical decision to platoon the catching spot during the season. Parrish appeared in 85 games and had 304 plate appearances, hitting .219 with 14 home runs and 41 RBIs. He was disappointed in his season and indicated that it was the first time he had platooned in his career. “I felt good in spring training. I had a lot of confidence going into the season,” he said. “Then, all of a sudden, I lost it. When you’re in and out all the time, it makes it hard to get any momentum going.”

But Lance’s personal life had a positive change as he married Arlyne Nolan after the 1978 season. They were married while Parrish Lance played winter ball for Mayaguez in Puerto Rico. His bride was a former Miss Diamond Bar, Miss Hollywood, and Miss Southern California, and first runner-up Miss California. She met Lance while rooming at his home during her senior year in high school. “It was nice to find out the best-looking girl in school was going to stay at your house,” said Parrish, who is 21 months her junior. Their wedding banquet included hamburgers at a Dairy Queen in the Virgin Islands.

Houk retired from managing (at least for the time being) and was replaced by Les Moss after the 1978 season. Parrish was “going to be the next superstar in the American League,” Moss said. “He will be one of the best in the business. He has tremendous power and throws as good as anybody. When I had him at Evansville, he was the best player in the league. I think he’s ready to be an outstanding player.”

In 1979 Milt May was sent to the Chicago White Sox during the Memorial Day weekend to clear the way for Parrish. May said he had all but demanded that the Tigers trade him as far back as spring training when Moss, speaking candidly, told him that Parrish would be the No. 1 catcher that year. Parrish must have gained some confidence immediately after the trade; he won the American League Player of the Week honor after he hit .591 (14-for-27) with an on-base percentage of .567 and slugging percentage of .852. (Through May 30 he had hit.320.) After Les Moss had managed the Tigers to a 27-26 record, the Tigers made a bold move by firing him on June 12 and hiring Sparky Anderson, who had won two World Series with the Cincinnati Reds. Parrish received some positive news the next day, though, as his first son, David Michael Parrish, was born on June 13. (David played baseball for the University of Michigan and was drafted as a catcher by the New York Yankees.)

Parrish ended his 1979 season with a .276 batting average and contributed to the Tigers’ offense by launching 19 homers and knocking in 65 runs. He did, however, have the dubious distinction of leading the American League in passed balls with 21. This became a perpetual problem — as of 2010 he held the career record for passed balls by a catcher (192). “I divide the season in two, I was satisfied at the plate, but disappointed defensively,” Parrish said after the ’79 season. “I did too many things wrong, too many passed balls. There’s a lot I’ve got to work on.” Parrish did rank second in the league in catcher assists. “I’m not worried about Lance,” Anderson said. “He learns quickly and will be our leader on this team for a long time. He’s one of our undiscussables.” After the season, Major League Baseball placed Parrish on the American League roster to tour Japan and play nine games. He hit two home runs in Japan. “The Japanese pitchers drove me wild,” Parrish said. “They’re all side-armers over there.”

Anderson decided at spring training in 1980 that he wanted to get Parrish some playing time in the outfield and at first base to give him some rest at catcher and add longevity. But Parrish was injured in spring training during a collision at first base with former Tiger Ron LeFlore, then with the Montreal Expos. Once the season started the team slumped, but Parrish maintained a .300 batting average for a while and showed more confidence. “It shows in the dugout,” said Anderson. “Lance is talking it up with the pitchers more. You can see that he is handling them with more authority.” Relief pitcher John Hiller said, “The pitchers aren’t shaking him off as much as they used to, he calls an excellent game now.” Parrish did show off a bit of a temper in a game in Oakland on May 3, as he broke a water cooler pipe after the A’s stole some bases against Morris and him.

Parrish made his first appearance in an All-Star Game on July 8, 1980, at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. Parrish struck out against Bruce Sutter as the National League prevailed, 4-2. The Tigers’ season was frustrating as they finished in fourth place. Parrish missed the final week after suffering a fractured right wrist when he was hit by a pitch. Parrish finished the season with a .286 batting average, 24 home runs and 82 RBIs. He won his first Silver Slugger award, given to the best offensive player at each position.

In the strike-shortened season of 1981 Parrish struggled and hit .244 with 10 home runs and 46 RBIs. In May, pitching coach Roger Craig started calling pitches. In 1982 Anderson said, “Lance will never be a leader with his mouth, and the sooner people realize it, the better off we’ll be. He is not one to pop off. He gets things done in his own way and I kind of envy him.” For his part, Parrish said, “I’m enthusiastic, but I have to do things my own way. People think I’m lazy. I hear that all the time. I’m not. It’s just that I can’t be something I’m not, and what I’m not is a catcher who is always jumping up and down and gets excited. I get just as fired up as the next guy, but I don’t have to get crazy to show it.”

Parrish had a tough start in 1982, straining ligaments in his left hand on a checked swing in the second game of the season, against Kansas City. But on April 27, in his first game back in the lineup, Parrish hit a home run. He hit safely in 18 of 21 games and raised his batting average to .309. Anderson suggested that Parrish would hit better if he stayed away from weightlifting. “Look at him, he’s a lot looser now and he’ll get even more so the longer he stays away from the weights. … Lance can become anything he wants in this game,” Anderson said. Parrish played in the 1982 All-Star Game, held in Montreal. Taking over from Carlton Fisk in the fifth inning, he set an All-Star game record by throwing out three runners, Steve Sax, Ozzie Smith, and Al Oliver, trying to steal second base. Parrish went 1-for-2 as he doubled off Cincinnati’s Mario Soto.

After the All-Star Game Parrish homered in three consecutive games. The 1982 season became even more special as the Parrishes had a second son, Matthew Thomas Parrish, born on August 25. (Matthew played as an outfielder in the Tigers’ minor-league system.) The Tigers, who had built up a record of 35-19 by June 12, struggled and went 16-32 afterward to send them back to .500; they finished 83-79, fourth in the American League East. Parrish, the highest-paid Tiger at $550,000, expressed displeasure with the team management. “We’re always a couple players short because the team is looking for ways to save money,” he said. “What we’re going through gets old after a while. The people who get ripped off are the fans.” Aside from that, the season was notable for him as he set a record for home runs in a season by an American League catcher. His 32 homers, 87 RBIs, and .284 batting average earned him another Silver Slugger award. He was named Tiger of the Year by the Detroit chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America.

The 1983 season was disappointing for the Tigers as they fell short of the Orioles in the pennant push. Parrish, however, became the first Tigers catcher in 45 years to drive in more than 100 runs. (It was the only time he had 100 or more RBIs in a season.) He finished with 27 homers and 114 RBIs. Parrish, Trammell, and Whitaker were awarded Gold Gloves. This was the first time in the history of the award that there were three winners on the same team.

Detroit got off to a sizzling start in 1984, and the fourth game, on April 7, was a harbinger of a special season. Jack Morris walked six batters, but more importantly allowed no hits by the White Sox at Comiskey Park. After the game, one of the clubhouse kids approached Parrish in the locker room: Jim Campbell had placed a call to the clubhouse. After Campbell spoke glowingly to Parrish awhile, Campbell suggested that there would be a bonus coming his way. But when Campbell realized he was talking to Parrish and not to Morris, Campbell told Parrish to get off the phone — and that would be no bonus.

Parrish continued to show leadership with the team and especially with Morris. On May 8 Morris lost his composure in a game. “Nobody likes to play behind you when you act this way,” Parrish told him. The ace was crushed. “Lance saved me,” said Morris. “I try, but sometimes I can’t control myself. I needed something. Lance has so much more class than I have. I’m not going to cross Lance. He’s like a big brother to me and he knows just what to say to me.” Baseball fans selected Parrish to start for the American League in the All-Star Game. “I feel like I’ve come a long way,” he said. “This puts me over the hump. People are realizing and appreciating my ability.”

Despite a much lower batting average that season (.237), Parrish had 33 homers and 98 RBIs to cap a wonderful Tigers season, and he won the Silver Slugger and Gold Glove awards. Lance played in his first and only World Series, against San Diego.

“I’m sure no one is going to accept the fact we are as good as we are unless we win it all and that’s what everyone on this team intends to do,” Parrish said. “I don’t know what else you can ask of this club but all you hear about is the fact we got off to that 35-5 start. It seems to me we played the rest of the way pretty well too.” He hit a homer in the American League Championship Series against the Kansas City Royals and the one off Gossage in the World Series. The 1984 season was also special for Lance as his wife gave birth to a daughter, Ashley, on October 4.

Parrish had a unique moment in 1985 as he received a kiss from Morganna the Kissing Bandit during the NBC telecast of the Tigers-Angels game on June 1. Parrish was concerned about the incident because after she kissed Fred Lynn, the Orioles’ outfielder went 3-for-40 at the plate. After a good start to the season, the Tigers lost 24 of 45 games. Parish did not catch from July 10 to July 29 due to a strained lower back. The Tigers and Parrish’s agent, Tom Reich, were close to a long-term deal, but there concerns about the back injuries. Still, Parrish won another Gold Glove.

In 1986 Jim Campbell, by this time the team president, said player contracts should last no more than three years — or maybe even just one year. Parrish said he was disappointed by Campbell’s new philosophy. “I’d like to play in Detroit my entire career,” he said. “I haven’t had any problems with the Tigers in the past about contracts. I really don’t anticipate any now. When the time comes, I think we can work something out, at least I hope we can.” Anderson had a goal of having Parrish, despite his creaky back, catch 120 games in 1986 with the remaining games at first or as designated hitter. Still, Parrish caught 39 of the first 41 games at catcher and hit his 200th career home run. He had 21 homers and 59 RBIs at the All-Star break. Then he went on the disabled list with a sore back. Despite the long-term injury, Parrish won his fifth Silver Slugger award. After the season, Parrish took part in a rigorous therapy program.

For 1987 the Tigers, wary of Parrish’s back problems, offered him $850,000, the same salary as the previous season. Parrish declined arbitration and became a free agent. He did not like the way he was treated by the Tigers and Campbell, and decided not to sign a contract with the only major-league team that he had known. On March 13, 1987, he signed with the Philadelphia Phillies, though the negotiating process became tedious. Phillies President Bill Giles insisted that Parrish accept a provision that he could not sue Major League Baseball or file a grievance over collusion allegations. The contract provided Parrish with additional money if he was able to stay off the disabled list due to a back ailment. It helped that one of Parrish’s best friends from their Tigers days, outfielder Glenn Wilson, played for the Phils. Lance was also good friends with the Phillies’ perennial All-Star third baseman, Mike Schmidt. “I’m very happy it’s over,” Parrish said of the contract talks. “I’ll miss my teammates at Detroit, but I had to do what was best for Lance Parrish. I realize there are those concerned about my back condition. But I never felt better. I’m going to prove them wrong.”

But Parrish struggled through much of the 1987 season. Opposing baserunners stole 13 straight bases against him early in the season. At the 29-game mark, he had a batting average of .187 with four homers and 14 RBIs. The Tigers had moved on with catchers Matt Nokes and Mike Heath. Parrish blamed Sparky Anderson for his hitting problems with the Phillies. He said he believed that Anderson had advised National League managers how to pitch to him. “Tell Sparky he did a good job,” said Parrish, who in early July was hitting .224 with seven home runs and 34 runs batted in. In August he hit .290 with five homers and 15 RBIs despite being booed by Veterans Stadium fans. Parrish concluded his disappointing season by hitting .245 with 17 home runs and 67 RBIs.

Parrish had the opportunity to be a free agent again, but re-signed with the Phillies on a one-year deal. He made the National League All-Star team, but his batting average dipped still further, to .215. The Phillies did not perform as the pundits had expected. “There was not a winning attitude,” Parrish said. “It always seemed that we were in a tight game and we just didn’t do the right thing to win. I think everybody should accept some of the blame.”

Parrish left Philadelphia on October 3, 1988, when he was traded to the California Angels for a minor leaguer, David Holdridge. He waived his right to free agency based on arbitrator George Nicolau’s ruling that major-league baseball colluded to keep salaries down and to make it difficult for free agents to leave their teams. Former teammate Kirk Gibson had elected to leave the Tigers prior to 1988 and play for the Los Angeles Dodgers. The decision turned out well for Gibson. He was the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1988 and led the Dodgers to the World Series championship over the Oakland Athletics. Parrish had the choice of returning to Detroit or going to the Angels. Returning to the Tigers “would’ve meant again packing up my family (already settled in Yorba Linda, a suburb of Anaheim). It was just so much easier this way. Collusion was a very convenient excuse for the teams. It started with the Tigers making an issue out of the back to hold down my salary.”

Parrish replaced Bob Boone, the longtime Angels catcher, in Anaheim and received much credit for handling the starting pitchers. He was thought to have contributed significantly to the Angels’ pitching staff having a 2.69 ERA into June. Kirk McCaskill, Chuck Finley, Bert Blyleven, Jim Abbott, and Mike Witt formed the Angels’ rotation. Parrish had a spark in his offense as he started using a 36-inch, 36-ounce bat, bigger than the one he had used for the earlier part of his career. The injury bug bit Parrish as he hurt his ribs in a collision with Milwaukee’s Glenn Braggs. Still, he caught in 122 games, had a good season, and signed a three-year deal with the Angels.

Parrish had some happy years back home in California. On April 12, 1990, he backstopped a no-hitter shared by Mark Langston and Witt, and he won a sixth Silver Slugger award. Only Mike Schmidt and Parrish had six Silver Slugger awards at that point. At the age of 34, he had a .268 batting average with 24 homers and 70 RBIs in 1990. In 1992 he became the eighth catcher to reach 1,000 games with 1,000 RBIs. Six of the eight are in the Hall of Fame, with Parrish and Ted Simmons being the exceptions.

Parrish concluded his career with short stints in Seattle, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Toronto from 1992 to 1995. He played briefly with Albuquerque in the Dodgers’ system and with the Toledo Mud Hens in 1994 in an attempt to play again with the Tigers. His last major-league game was with the Toronto Blue Jays on September 23, 1995. Parrish was struck out by Joe Hudson in the ninth inning against the Boston Red Sox in Fenway Park.

After his playing career ended, Parrish was a minor-league catching instructor for the Kansas City Royals in 1996. He coached the San Antonio Missions in 1997 and 1998, taking over as manager during 1998. From 1999 to 2001 he was a coach for the Tigers, then a television color analyst for the Tigers in 2002, then a Tigers coach again through 2005. In 2006, Parrish was manager of the Ogden Raptors of the Pioneer League and was named inaugural manager of the 2007 Great Lake Loons of the Midwest League. The Loons went 57-82 and Parrish was fired after one season. Afterward, he and Arlyne moved from California to Nashville, Tennessee, although in 2010 he expressed his desire to get back into the game.

Parrish’s playing career concluded with 324 homers, three Gold Gloves, six Silver Slugger awards, and eight All-Star team selections. Even though he played with other teams, Lance Parrish will always be known for helping the Tigers by using his catching and hitting prowess so that the Tigers could achieve one of their four world championships in 1984.

Sources

Publications

Zaret, Eli. ’84 The Last of the Great Tigers. South Boardman, Mich.: Crofton Creek Press. 2004.

Articles

The Sporting News

Baseball Digest

Sports Illustrated

Websites

http://www.baseball-almanac.com

http://www.baseball-reference.com

http://www.minorleaguebaseball.com

http://www.retrosheet.org

Full Name

Lance Michael Parrish

Born

June 15, 1956 at Clairton, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.