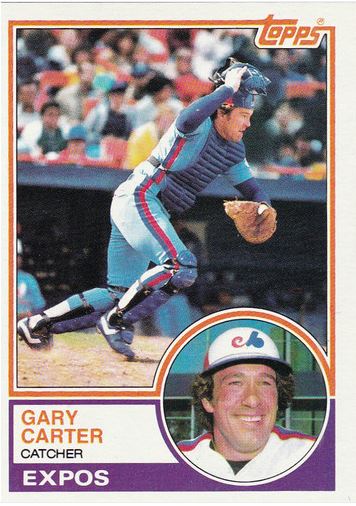

Gary Carter

It simply should not have taken six years for Gary Carter to get into the Hall of Fame. He was one of the best catchers of his era, and many observers put him in the top ten in major-league history. He was an outstanding defender with a strong arm who did all the other things expected of a receiver. He combined that with a powerful bat – Carter’s 298 homers as a catcher are sixth-most at that position – and a gung-ho competitive spirit. A broad grin and pumping fist were The Kid’s visual trademarks.

Carter’s best years came with the Montreal Expos in the late 1970s and early ’80s, but he was still in his late prime when he joined the New York Mets in 1985. Carter was the final ingredient that helped a promising young club become a World Series champion in 1986. He became the team’s cleanup hitter and handled its excellent pitching staff. One of those hurlers, Ron Darling, called Carter the moral compass of the hard-living squad.1

Knee injuries ground Carter down – in part because he always wanted to stay in the lineup. His last season as a full-time regular came at age 34 in 1988, though he hung on for four more years. Subsequently, he stayed involved in baseball as a broadcaster with the Florida Marlins and Expos. He then coached and managed in the minors, independent ball, and college, but his hopes of returning to the majors went unfulfilled. Alas, Carter also died in 2012 at the too-young age of 57.

For the definitive account of this man’s youth and family background, one must turn to Before the Glory (2007), by Billy Staples and Rich Herschlag. All the details one could want are in Carter’s chapter, as told by The Kid himself. Of necessity, this story offers only a tiny selection.

Gary Edmund Carter was born on April 8, 1954, in Culver City, California, near Los Angeles. He was the second of two boys born to James H. Carter and his wife Inge. Jim Carter, a mechanically minded man from Kentucky, moved to California after World War II to work in technical jobs in Hollywood. When Gary was born, he was working as an aviation-parts inspector for Hughes Aircraft Company.2 (The aerospace industry was a big employer in Southern California.)

Inge Charlotte Keller was born in Chicago in 1929. Her parents were German immigrants who came to the U.S. in the 1920s. Gary later attributed his athletic ability to Inge, a champion swimmer, although Gary himself said, “Funnily enough, I’m a terrible swimmer.”3 His older brother Gordon was also good enough to be a second-round draft pick of the California Angels in 1968 and the San Francisco Giants in 1971. Gordy played two years of Class A ball (1972-73) in the Giants organization.

Gary Carter started playing Little League at age six, but he also loved and was talented at football. In 1961, the National Football League sponsored the first Punt, Pass & Kick contest. At the Los Angeles Coliseum, seven-year-old Gary became the national champion in his age group. He was a finalist again two years later, but lost in sub-zero conditions in Chicago.

When Carter was 12 years old, his mother died at age 37 after a battle with leukemia. This crushing loss at a young age was at the root of Carter’s later charitable work, raising funds for leukemia research and on behalf of children with other disorders. Jim Carter took on the role of both parents, making great sacrifices for his boys. In addition to his job in procurement for McDonnell Douglas, another aerospace/defense company, he coached Gary at various levels of youth baseball and supported him in all his sporting endeavors.4 Brother Gordy was also a mentor and role model for Gary.

Carter followed Gordy to Sunny Hills High School in Fullerton, California (the family had moved there when he was five). There he was a three-sport star, becoming captain of the football, basketball, and baseball teams. He was also a member of the National Honor Society. In football, he was a high school All-America quarterback and received nearly 100 scholarship offers. He signed a letter of intent with UCLA. (If he had played for the Bruins, he would have competed with and/or backed up Mark Harmon, who went on to become a well-known actor.) Carter suffered torn knee ligaments in his senior year, however, and had to sit out the football season. Noted sports surgeon Dr. Robert Kerlan warned him that one more bad hit could end his athletic career.5

That prompted Carter to turn pro in baseball instead. The Expos had selected him in the third round of the 1972 amateur draft. He had played shortstop, third base, and pitcher for Sunny Hills – and only six games as a catcher.6 But scout Bob Zuk, special assignment scout Bobby Mattick, and farm director Mel Didier looked at the ruggedly built teenager (6-feet-2, 205 pounds) and envisaged him behind the plate. Zuk also craftily downplayed his interest in Carter, which enabled Montreal to draft him earlier than other teams expected.7

Although Carter was totally raw as a receiver, his ascent through the minors was rapid. He played in rookie league and Class A in 1972 and jumped to Double A for 1973. He got his first promotion to Triple A at the end of ’73 and needed just one more year at that level in 1974, when he became the Topps Triple-A All-Star catcher. He never returned to the minors except for a brief injury-rehab stint in 1989.

According to Carter, he got his enduring nickname – “The Kid” – during his first spring training camp with the Expos in 1973. “Tim Foli, Ken Singleton and Mike Jorgensen started calling me Kid because I was trying to win every sprint. I was trying to hit every pitch out of the park.”8 One history of the 1986 Mets, Jeff Pearlman’s The Bad Guys Won, wrote that pitcher Don Carrithers (an Expo from 1974 to 1976) sarcastically hyped “The Kid” as a way to get the goat of incumbent catcher Barry Foote. Pearlman then went on at length to describe how Carter’s naïve enthusiasm rubbed a lot of his teammates the wrong way. Another nickname – “Camera Carter” – later came from his love of doing interviews. “Lights” and “Teeths” were two more labels that captured the behind-the-back sniping in Montreal.9

Yet there wasn’t anything phony about Carter – his chatty, cheery exterior truly reflected what was in his heart. As Ira Berkow of the New York Times wrote upon Carter’s induction to Cooperstown, “He delighted in relationships.”10

In that first camp in 1973, Montreal assigned Carter to room with John Boccabella, a veteran catcher. “Boc” was traded for Carrithers toward the end of March 1974, and after the deal, Boccabella said of Carter, “He impressed me both as a player and a person. He learns fast and I think he has the stuff to become a superstar.”11

Boccabella’s personal influence on Carter was even stronger. The veteran was a man of deep religious faith who attended Mass daily and had led Sunday services for the Expos. Carter, who had lost his faith after his mother died, found it again. As his daughter Christy recalled in 2013, “John Boccabella led Dad to Christ and he accepted Jesus in his heart.”12

Carter told Montreal sportswriter Ian MacDonald about this himself in 1977. He called Boccabella “a beautiful guy. Always enthusiastic. Always up. Always reading from the Scriptures or [basketball coach John] Wooden’s book. I had met Wooden two or three times when I was being recruited by UCLA but I hadn’t read the book until Boccabella gave me a copy. It was overwhelming. It reinforced everything that I believed in and gave me the physical strength to practice my beliefs – to be happy to be alive, to be enthusiastic, to not fill your life with hate over the stupid things…I learned a lot from ‘Boc’ and I’ll always be grateful to him.” 13

Playing winter ball in Puerto Rico also aided Carter’s development. He played for the Caguas Criollos in the 1973-74 season. Montreal sent a number of its prospects to Caguas, which was loaded with future big-leaguers. One of them, Otto Vélez, called that club the best Puerto Rican team he ever played on – they became league champions and went on to win the Caribbean Series. Vélez told author Thomas Van Hyning, “There was no envy on that team, though there were many who could really play. Gary Carter wanted to become a better player, [Mike] Schmidt had to overcome a season with a lot of strikeouts.”14

Carter started that winter in Instructional League, but a month into the Puerto Rican season, Caguas needed a backup catcher. Montreal’s general manager, Jim Fanning, recommended the 19-year-old, who became the youngest member of the Criollos. He got a chance to play when the regular catcher, Jim Essian, got hurt. As was true everywhere Carter played, the fans loved him for his enthusiasm and desire to win.15 In the Caribbean Series, Carter hit a homer off Pedro Borbón of the Dominican Republic and was named the catcher on the series all-star team.

The Expos called Carter up to the majors for the first time in September 1974. He made his debut at Montreal’s old Jarry Park on September 16. On September 28, also at Jarry, he hit his first of 324 regular-season homers in the majors. It came against a great pitcher, Philadelphia’s Steve Carlton. In 27 at-bats, Carter got 11 hits for a .407 average.

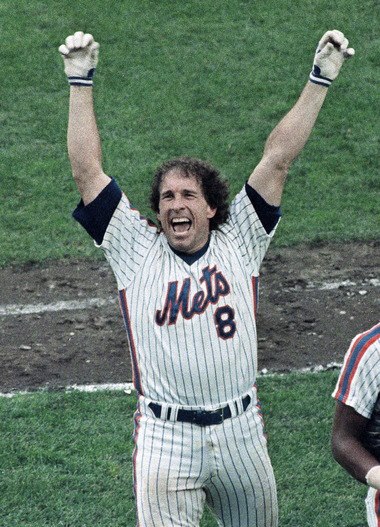

Carter wore uniform number 57 in that brief appearance. The following season, Carter was assigned the number 8, and considered it fate. “I was born on April 8. I got married on February 8. We moved into our first home in California on November 8. And look at all the great players who wore No. 8. Carl Yastrzemski. Willie Stargell. Yogi Berra. Bill Dickey. Joe Morgan. Cal Ripken, Jr. All Hall of Famers. So when I was assigned No. 8, I remembered all those things and figured it would be a lucky number for me, and it was,” Carter wrote in 2008.16 He wore it for the rest of his career.

Carter played with Caguas again in the winter of 1974-75. He hit .261 with five homers and 32 RBIs; of interest was that he alternated between catcher and third base. Though the Criollos wanted him behind the plate, Jim Fanning sought to get him action at third and in right field. The experiment at the hot corner was curious, since one of Montreal’s other prize prospects was third baseman Larry Parrish.17

The Criollos made it to the league finals once more, and had they repeated as champions, the resulting trip to the Caribbean Series would have endangered Carter’s wedding date. The Bayamón Vaqueros won in seven games, though – and so, on February 8, 1975, Carter married his high school sweetheart, Sandra “Sandy” Lahm.18 At the time, Sandy was training to be a flight attendant. The couple spent their honeymoon in the Expos’ training camp at Daytona Beach!19 They later had three children: Christina (“Christy”), Kimberly (“Kimmy”), and Douglas James (“D.J.”).

In March 1975, sportswriter Brad Willson of the Daytona Beach News-Journal wrote a spring-training feature about Carter and his enormous promise. He quoted Karl Kuehl, who had managed Carter in the minors and in Instructional League, as well as Jean-Pierre Roy, the Montreal native and former Brooklyn Dodger who later went into broadcasting with the Expos. They both gave glowing assessments – but what mattered even more were the opinions of Fanning and manager Gene Mauch.

Fanning said that Carter’s tools were as good as those of any player they had, but added, “He also has the intangibles not all the others possess – desire, determination, and hustle. He’s a superkid.” After much deliberation, Mauch said, “Gary Carter is a highly gifted, intelligent young man. In every league in which he’s played, he’s adjusted to the caliber of play. In Double A, Triple A and winter ball he had some difficulty at first. But he adjusted; that’s where the intelligence comes in. I’ve seen players who can run better and who can hit better but I’ve never seen a better package. I’ve never seen someone who loves to play the game more.”20

Carter finished second in the voting for National League Rookie of the Year in 1975 behind San Francisco Giant pitcher John “The Count” Montefusco. He was also named to his first of 11 All-Star teams. That year, however, he started 80 games in right field and only 56 behind the plate. Carter and Barry Foote continued to share the catching duties for Montreal in 1976, though Carter missed most of June and July after breaking his thumb in a “spectacularly ugly” outfield collision with Pepe Mangual.21 It was his worst season in Montreal.

The Expos had a new young star in right field: Ellis Valentine, who had power and a cannon arm. Carter seized the catching job from Foote in 1977. From then through 1984, he started 89% of the games that Montreal played and posted an OPS of .823 (simple averages of seasonal statistics are distorted by the strike of 1981). He won three Gold Gloves in succession from 1980 through 1982 and was runner-up to Mike Schmidt for the NL’s Most Valuable Player award in 1980. His Wins Above Replacement (WAR) numbers were consistently high.

At the plate, Carter was an imposing figure. Players were not nearly as bulked up in that era, and Carter had one of the burlier upper bodies in the game then. He gave the impression of using his upper half and especially his forearms when he swung – it was a chopping horizontal stroke, like a lumberjack attacking a tree. He stood up almost straight at the plate, with just a slight knee bend; he held his bat high and nearly vertical.

As a receiver, Carter cited his own hard work and natural progression with experience, especially once he could focus on catching full-time. He also seconded the opinion that Norm Sherry, whom Expos manager Dick Williams had hired as catching coach after the 1977 season, had been a very helpful tutor.22

Carter remained one of the best in the game at stopping enemy runners. From 1974 through 1976, he threw out 49% of would-be base stealers (49 of 99). That ratio remained at 40% from 1977 through 1984 (481 of 1189). Larry Bowa, who stole over 300 bases in the majors, offered extra insight in 2003. “This guy put a little fear in you when you were on first base even if you got a good jump…A lot of catchers were on ego trips, they didn’t want you to steal, so they would call just fastballs…I respect Gary Carter because he would call breaking balls. He was not intimidated by any base stealer. He would call his game.”23

The Expos became one of the better teams in the National League in the late 1970s, thanks to Carter, Parrish, Valentine, André Dawson, pitcher Steve Rogers and other members of a homegrown core. In 1981, they made it to the postseason for the only time in the franchise’s history. Carter was 8 for 19 with two homers as Montreal beat the Phillies in five games in the NL Division Series. He was 7 for 16 in the NL Championship series against the Dodgers, and drew a walk in the bottom of the ninth after Rick Monday’s homer had put L.A. ahead. The Expos could not get the tying run in, though, and their chance for a pennant was gone. They fell back to third place in 1982, despite another strong year from their catcher.

Ahead of the 1983 season, Sports Illustrated put Carter on its cover, proclaiming him “The Best in the Business.” In the accompanying feature article, Ron Fimrite covered Carter’s game and personality in depth. Among the notable points, in summary:

Batting: It wasn’t just about slugging for Carter – he had worked to cut down on his strikeouts. “I’ve learned to be more disciplined,” he said. “If you want a sacrifice, I’ll do it. If you need someone to go to right field on the hit-and-run, I’ll do that.”

Fielding: Aside from his strong arm and quick release, Carter excelled at all the other valuable catching skills – framing pitches, blocking the plate, and calling the game. Fimrite also observed, “Carter’s nonstop commentary behind the plate has been known to drive even the most single-minded and level-headed hitters to distraction.”

Character: Beyond the ceaseless boyish enthusiasm (which caused cynics to doubt his sincerity), the genial Carter could also get angry on the field. He once shattered Bill Buckner’s bat and the two came to blows. Johnny Bench called Carter, “a fiery, forceful, aggressive player.”24

In February 1982, Carter had signed a seven-year contract for roughly $14 million plus incentives – then the sport’s richest deal, or close to it. “He’s a franchise-type player,” said Expos president (and general manager) John McHale. “If you can ever justify paying that kind of money, he’s one who earns it.”25 The Expos could not make it back to the playoffs, though, and owner Charles Bronfman was disappointed because he was also losing money on the club. In September 1983, Bronfman said, “Two months before Carter signed the contract, we were perfectly aware we were making a mistake. The next day and a month later we still knew we were wrong. I’ll know it until my dying day. And I’m not just saying that because Carter had a bad year.”26

Indeed, Carter had fallen off with the bat while battling assorted injuries. He bounced back in 1984, but Montreal still finished fifth in the NL East. The club decided it was time to reload and get value for their star. (John McHale also said that Carter wanted out, though Carter denied that he broached the idea.27) That December, after lengthy talks, the Expos traded the catcher to the Mets. They got four players in return: infielder Hubie Brooks, catcher Mike Fitzgerald, outfielder Herm Winningham, and pitcher Floyd Youmans. Brooks moved to shortstop and gave the Expos some solid (if not huge) years. Fitzgerald was a good defender, though not a big hitter, whose career was spoiled by a badly broken finger in 1986. Perhaps the biggest setback for Montreal was the talented Youmans, who developed arm and substance abuse problems.

Meanwhile, Carter fit in immediately with the Mets. On Opening Day 1985, he hit a game-winning homer in the 10th inning at Shea Stadium, smacking former Met Neil Allen’s 1-0 curveball over left fielder Lonnie Smith’s head and the fence. The delighted Met fans roared and Carter got his first-ever curtain call. “I learned right away that New York was going to be different,” Carter wrote later. “I was now playing for a special breed of fans. If hitting a walk-off home run in your first game with a new team is not special, I don’t know what is.”28

He set a career high with 32 homers that year while making less visible yet invaluable contributions. Manager Davey Johnson later called Carter “a one-man scouting system.” Both Johnson and Ron Darling observed how important the catcher’s detailed knowledge of hitters was to working with the talented but young staff.29

Carter was back on a home field with natural grass at New York’s Shea Stadium, which helped ease his main physical concern. In a 2010 interview, he referred to “that god-awful Olympic Stadium [in Montreal] that tore our knees up, ’cause I’ve had 12 knee surgeries and both my knees replaced.”30 Torn cartilage was a concern in mid-1985, but he gutted it out with a brace and waited until the season was over before getting arthroscopic surgery.

The Mets could not overtake the St. Louis Cardinals in 1985, but ran away with the NL East in 1986. Carter had his last truly big year, remaining a near-constant in the lineup except for a two-week stretch on the sidelines in August. (He hurt his thumb diving for a ball during one of his occasional starts at first base.) He finished third in the NL MVP voting.

During the National League Championship Series against the Houston Astros, Carter got just one hit in his first 21 at-bats. But in the bottom of the 12th inning of Game Five, with the count full, he hit a game-winning single. It was a grounder up the middle, past Astros reliever Charlie Kerfeld (who, according to some viewers, had taunted Carter by showing him the ball after making a behind-the-back play in Game Three). Carter said after the game, “I kept telling myself, ‘I’m going to come through here.’ I knew it was just a matter of time.” At that point – he had no idea of the drama to come – he also said, “It’s at the top of all the games I’ve ever played in.”31

After the Mets finally overcame the Astros – the concluding Game Six was an excruciating 16-inning battle – they faced the Boston Red Sox in the World Series. Carter was 8 for 29 (.276) with 9 RBIs. He cracked two homers in Game Four at Fenway Park as the Mets tied the Series. Yet his most crucial hit came three days later, in Game Six. Carter’s single in the bottom of the 10th sparked the most improbable two-out, three-run rally that snatched the championship away from Boston.

After the Mets finally overcame the Astros – the concluding Game Six was an excruciating 16-inning battle – they faced the Boston Red Sox in the World Series. Carter was 8 for 29 (.276) with 9 RBIs. He cracked two homers in Game Four at Fenway Park as the Mets tied the Series. Yet his most crucial hit came three days later, in Game Six. Carter’s single in the bottom of the 10th sparked the most improbable two-out, three-run rally that snatched the championship away from Boston.

In 2012, teammate Bob Ojeda said, “If you watch the video with Gary walking to the plate, you see that sense of determination…in his step, in his swing. . .he was not going to make that out. You can see [it] in his face.”32 Carter told reporters exactly the same thing after the game. According to first base coach Bill Robinson, when Carter reached base, he let loose a rare expletive –“No f***ing way” – to intensify the statement.33 (Carter is credited with coining the euphemism “f-bomb” in 1988.34) It’s also noteworthy that he had donned his catcher’s gear, ready to play another extra inning, when the winning run scored on the ball that got by Bill Buckner.

In April 1987, Carter published the first of his three books, A Dream Season. That year, the physical pounding of his position became harder to endure. Ahead of the 1988 season, the Palm Beach Sun-Sentinel wrote, “It took six cortisone shots [for Carter] to get through last season – to sustain a troublesome ankle, knee, shoulder, back and elbow. No wonder his offensive production slipped (.235, 20 HR, 83 RBI).” Carter said, “I was hurting every day last year. I should have been put on the disabled list several times, but they weren’t disabling injuries. In my early- to mid-20s, a lot of the type of injuries I have today were easier to shake off. You learn to appreciate the good days in which you feel like a human being.”35

That spring, Davey Johnson also made Carter a co-captain of the Mets. In 2012, Johnson said, “I had a captain of the team – Keith Hernandez, he ran the infield – before Gary got there, but after seeing what he did, he was so special, I made him a co-captain. It was an honor he deserved.”36 The drop-off continued, however: even though Carter still started 116 games behind the plate, his basic batting line fell off to .242-11-46. His caught stealing percentage also hit a career low of 19%. He was 6 for 27 in his final postseason activity, as the Mets lost the NLCS to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

The decline was even more severe in 1989 – Carter played in a career-low 50 games after knee problems forced another arthroscopy, costing him nearly three months from early May through late July. He hit just .183-2-15 in 153 plate appearances. The Mets released him (and Hernandez) after the season. In typical form, Carter said, “I know I can still play this game. I know there will be an opportunity out there.”37

In January 1990, he signed as a free agent with the San Francisco Giants. He platooned with another veteran, Terry Kennedy, who had been with the Giants during their pennant-winning season in 1989. Nonetheless, he still had the desire to play every day and didn’t want to hang on if he wasn’t contributing.38 Indeed, he made a respectable comeback (.254-9-27 in 92 games).

Even so, Carter became a free agent again, and did not sign with another team until March 1991. This time it was the Dodgers, the team he had followed as a boy. He made good on a non-roster invitation from manager Tommy Lasorda and backed up Mike Scioscia. When Scioscia was sidelined by a broken hand, Carter played every game for two straight weeks, including both ends of a doubleheader against the Braves. He did another creditable job (.246-6-26, while throwing out 32% of base stealers).

Late 1990 and early 1991 marked the release of a series of baseball novels for young adults under Carter’s aegis. The Gary Carter’s Iron Mask books followed a youth named Robbie Belmont – who wore number 8 and had been converted to catcher – from high school to the majors. Carter did none of the writing, but he signed the introductions and shared in the royalties. In 2014, author Robert Montgomery said, “I did meet with Gary before a game for an hour interview, and found him high-energy and very forthcoming. I sent him a few follow-up questions after the interview, which he promptly answered.”39

Carter did not file for free agency after the 1991 season, and the Dodgers placed him on waivers. As a result, he returned to Montreal in 1992 for his final year as a big-leaguer. He said it was something he’d always had in the back of his mind.40 At age 38, his teammates still called him “The Kid.” As it developed, he played more than any other catcher for the Expos that year, and though he didn’t hit much (.218-5-29 in 95 games), he still helped the team rebound from sixth place to second in the NL East. Carter went over the 2,000 mark in games caught and the 1,200 mark in RBIs in 1992, both milestones he wanted to achieve.

Carter’s career ended on an upbeat note. At Olympic Stadium on September 27, he drove in the game’s only run with a double. As he told it in 2004, “I had announced my retirement, and [manager] Felipe Alou said, ‘You will catch that game.’ In the seventh inning, in my last at-bat, I got the opportunity. Felipe Alou was going to pull me out of the game. He said, ‘Go on up there. Whatever happens, happens, but this is your last at-bat.’ It turned out to be a game-winner in front of that fan appreciation crowd. Nice way to finish.”41

After retirement, Carter became a color commentator on television for the Florida Marlins. He held that job for four years, but his contract was not renewed after the 1996 season.42 Shortly thereafter, he returned once more to the Expos, working in their TV broadcast booth from 1997 through 1999. His main focus in 2000 was golf with the Celebrity Players Tour. Carter felt a desire to get back on the field, though – as early as 1998, he had expressed managerial ambitions.43 In 2001 and 2002, he was a part-time roving catching instructor in the Mets minor-league system.44 He took on that role full-time in 2003 and became minor league catching coordinator in 2004.45

Off the field, Carter’s strong character manifested itself again in 1995, when the Internal Revenue Service began investigating active and retired ballplayers for failing to report income earned from appearances and autograph signings at baseball card shows. Under the microscope were Met stars Darryl Strawberry, Lenny Dykstra, Hernandez, Darling, and Carter. But when the IRS subpoenaed Carter to appear before a grand jury, they found that he was as honest about his taxes as everything else in his life. Carter spent $25,000 in accountants’ fees to produce his invoices and receipts. When he left the witness stand and the courtroom, he said, “There was nothing the US Attorney’s office was ever going to be able to question me about.”46 Carter was swiftly dropped from the probe.

On another front, the Gary Carter Foundation began operations in 2000. Its mission, through its own donations and funds raised externally, is to better the physical, mental and spiritual well-being of children in addition to supporting faith-based initiatives. Among the endeavors it supports is the Autism Project of Palm Beach County, Florida. The Carter family made its home there for many years.

Carter was finally elected to the Hall of Fame in 2003, his sixth year of eligibility. The vagaries of the process are well known, but his pattern was still unusual. In his case, “first-ballot” bias may have reflected his lack of milestone career numbers, yet Carter suffered an odd dip in his second year before gaining momentum.47 The voting disparities between him and two other top catchers of his day – Carlton Fisk and Lance Parrish – were also peculiar.48

Carter’s Hall of Fame plaque shows him in an Expos cap. He suggested that “it would be nice to have a split hat” that also featured the Mets, but the decision rested with the Hall, and he abided by it.49 During his induction speech, Carter grew very emotional as he honored his parents’ memory – Jim Carter had died that January, less than a month after his son was voted in – and thanked his brother Gordy.50

In 2004, the press bandied Carter’s name about as a future manager of the Mets after some grooming in the minors.51 He drew some flak for lobbying for the job with the big club that September, while Art Howe was still the incumbent.52 Carter got his first opportunity as a skipper in 2005 and led their rookie-ball club in the Gulf Coast League to a 37-16 record. He then had another winning season with the St. Lucie Mets of the Florida State League (high Class A). In both 2005 and 2006, Carter was named Manager of the Year in his league. The Mets offered him a job with their Double-A affiliate, Binghamton, for the 2007 season. He turned down that promotion, however, citing the rigors of the long Eastern League bus rides.53

Carter was also disappointed not to have landed a coaching job with the Mets’ major-league squad – he wanted to bring his experience and inspiration. He hinted that it might have helped as the club folded down the stretch in 2007.54 As it developed, he took all of 2007 off. In 2008, though, he returned to managing with the Orange County Flyers (based in Fullerton) of the Golden Baseball League. That March Carter again voiced his desire to manage the Mets, while Willie Randolph still held the job.55 He stayed in Orange County and again was named Manager of the Year.

For the 2009 season, Carter was skipper of another independent team, the Long Island Ducks of the Atlantic League. After his year with the Ducks, he became head baseball coach at Palm Beach Atlantic University in Florida. That was near his home in Palm Beach Gardens. Carter joined his daughter Kimmy, who had been a star catcher in softball at Florida State University from 1999 through 2002. She was named head softball coach at PBA in 2007.

In May 2011, Carter began to experience headaches and forgetfulness. He was diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. His case was inoperable, but he fought it with a course of radiation and chemotherapy, displaying the same positive outlook and competitive fire as always. Kimmy chronicled the grueling battle in an extensive journal on the website CaringBridge.org. The account was filled with hope and faith, which continued even after a magnetic resonance imaging scan showed the presence of several new spots on Carter’s brain in January 2012.

Carter’s assistants had taken over his coaching duties at Palm Beach Atlantic, but he visited his team on February 2, 2012, when it opened its season in Jupiter, Florida, against Lynn University. It was his last public appearance – two weeks later, he died in hospice care. He was survived by his wife, three children, and three grandchildren.

The Expos retired Carter’s uniform No. 8 in 1993, and it retains that status with the Washington Nationals (which the Expos became after the 2004 season). There have been frequent calls for the Mets to do likewise. In May 2013, the city of Montreal renamed a section of a street – adjacent to Jarry Park – Rue Gary-Carter. The following month, it inaugurated Gary Carter Stadium in Ahuntsic Park. A crowd of old Expos diehards greeted Gary’s widow Sandy and daughter Christy, who emphasized how much Montreal meant to the Carter family.

Gary Carter captured essential parts of himself in the titles of his two other books, The Gamer (1993) and Still a Kid at Heart (2008). Yet to round out the picture, one may choose from among the many tributes this man received from his teammates after his passing. Perhaps the most fitting came from Darryl Strawberry, “I wish I could have lived my life like Gary Carter…He was a true man.”

This biography is included in the book “The 1986 New York Mets: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Leslie Heaphy and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Christy Carter Kearce for her input. Continued thanks to David H. Lippman for his input during peer review.

Sources

Internet resources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.garycarter.org

Books

Billy Staples and Rich Herschlag, Before the Glory, Deerfield Beach, Florida: Health Communications, Inc., 2007.

Gary Carter and Phil Pepe, Still A Kid At Heart, Chicago, Illinois: Triumph Books, 2008.

Billy Staples and Rich Herschlag, Before the Glory, Deerfield Beach, Florida: Health Communications, Inc., 2007.

Notes

1 Tim Kurkjian, “This ‘Kid’ had a passion for the game,” ESPN.com, February 16, 2012.

2 Laurence Arnold, “Gary Carter, ‘Kid’ Who Helped Mets Win 1986 World Series Title, Dies at 57,” Bloomberg.com, February 17, 2012

3 Jim Murray, “He’s Hunkered Down and Worthy of Being the MVP,” Los Angeles Times, September 12, 1985.

4 Barry M. Bloom, “Carter dedicates speech to parents,” MLB.com, July 27, 2003. Murray, “He’s Hunkered Down and Worthy of Being the MVP”

5 Ron Fimrite, “His Enthusiasm Is Catching,” Sports Illustrated, April 4, 1983. Ian MacDonald, “Gary Carter finding his niche,” Montreal Gazette, October 7, 1977, 17.

6 Ian MacDonald, “Carter Winning Universal Acclaim for Canadian Progress Program,” The Sporting News, June 9, 1979, 3.

7 Andy O’Brien, “The Bubble Gum Kid,” Windsor (Ontario) Star, May 3, 1975.

8 “Montreal’s ‘The Kid’ tabbed baseball’s best,” Associated Press, May 9, 1981. Richard Goldstein, “Gary Carter, Star Catcher Who Helped Mets to Series Title, Dies at 57,” New York Times, February 16, 2012.

9 Jeff Pearlman, The Bad Guys Won, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2004, 89, 91.

10 Ira Berkow, “Two Different Stars Find Same Reward,” New York Times, July 28, 2003.

11 Tim Burke, “‘Boc’ gets what he hoped for with trade to San Francisco.” Montreal Gazette, March 28, 1974, 35.

12 E-mail from Christy Carter Kearce to Rory Costello, October 15, 2013.

13 MacDonald, “Gary Carter finding his niche”

14 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995, 133.

15 Héctor Barea, “Gary Carter,” El Nuevo Periódico (Caguas, Puerto Rico), February 29, 2012

16 Gary Carter and Phil Pepe, Still A Kid At Heart, Chicago, Illinois: Triumph Books, 2008, 22.

17 Bob Dunn, “Expos Place Carter, Parrish Under Lock and Key,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1974. Bob Dunn, Expos Searching for Spot to Play Prospect Carter,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1975, 47.

18 Billy Staples and Rich Herschlag, Before the Glory, Deerfield Beach, Florida: Health Communications, Inc., 2007, 164.

19 O’Brien, “The Bubble Gum Kid”

20 Brad Willson, “Press Box,” Daytona Beach News-Journal, March 23, 1975, 1B, 7B.

21 Bob Dunn, “Docs Work Overtime Repairing Expo Cripples,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1976, 25. Mangual suffered a concussion.

22 MacDonald, “Carter Winning Universal Acclaim for Canadian Progress Program”

23 Tim Kurkjian, “Congrats to The Kid,” ESPN The Magazine, January 7, 2003.

24 Fimrite, “His Enthusiasm Is Catching”

25 Fimrite, “His Enthusiasm Is Catching”

26 “Expos’ Chairman Claims Club’s Signing of Carter a Mistake,” United Press International, September 27, 1983.

27 Terry Scott, “Carter cleans out his Expos locker, sheds a few goodbye tears,” Ottawa Citizen, December 20, 1984.

28 Carter and Pepe, Still A Kid At Heart, 39.

29 Arnold, “Gary Carter, ‘Kid’ Who Helped Mets Win 1986 World Series Title, Dies at 57.” Kurkjian, “This ‘Kid’ had a passion for the game”

30 Patrick Reddington, “Hall of Fame Catcher Gary Carter on the Washington Nationals, Montreal Expos and Tim Raines,” federalbaseball.com, August 11, 2010.

31 Dave Anderson, “‘I’m Not an .050 Hitter’,” New York Times, October 15, 1986.

32 Steven Marcus, “Gary Carter sparked Game 6 rally in 1986,” Newsday, February 16, 2012.

33 Kurkjian, “This ‘Kid’ had a passion for the game”

34 Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (2012 edition) gave this article as the earliest known usage: Steve Marcus, “Carter Thrives as Pinch-Hitter,” Newsday, August 11, 1988. See also David Haglund, “Did Gary Carter Invent the ‘F-Bomb’?”, slate.com, August 14, 2012.

35 Craig Davis, “Men Behind the Masks,” Palm Beach Sun-Sentinel, March 3, 1988.

36 Kurkjian, “This ‘Kid’ had a passion for the game”

37 Ronald Blum, “Carter, Hernandez released by Mets,” Associated Press, October 4, 1989.

38 Erik K. Lief, “Gary Carter adjusts to new role,” United Press International, May 12, 1990.

39 E-mail from Robert Montgomery to Rory Costello, November 14, 2014.

40 Joe Gromelski, “For Gary Carter, there’s no place like Montreal,” Lewiston (Maine) Sun-Journal, May 11, 1992, 25.

41 Steve Rosenbloom, “Gary Carter: Our guy catches up to ‘The Kid’,” Chicago Tribune, August 31, 2004, Sports-8.

42 Scott Tolley, “Marlins Let Randolph, Carter Go,” Palm Beach Post, October 2, 1996.

43 “Carter has managerial ambitions,” Kitchener (Ontario) Record, March 21, 1998, E4.

44 “Kid Glad to Be back,” New York Daily News, March 3, 2001.

45 “Carter back as roving minor league catching instructor,” MLB.com, December 13, 2002. “Gary Carter to manage St. Lucie Mets,” MLB.com, January 9, 2006.

46 Bob Klapisch, High and Tight, New York: Villard Books, 1996, 140-141.

47 Carter’s vote percentage started with 42% in 1998, dipped to 33%, and was still just 49% in 2000. He then gained momentum, rising to 65% and 73% before finally breaking through with 78%.

48 One voter, Jack O’Connell of the Hartford Courant, wrote about this – “Fisk, Carter: Why Not Kid in Hall?” – on December 29, 1999.

49 Kevin T. Czerwinski, Kid catches Cooperstown spotlight,” MLB.com, January 16, 2003. André Dawson and Tim Raines are the two other members of the Hall whose plaques show an Expos cap (though Dawson would have preferred to show the Chicago Cubs).

50 Bloom, “Carter dedicates speech to parents”

51 Kevin Kernan, “Kid Stays in the Picture – Carter Could Be Next Met Manager,” New York Post, July 4, 2004.

52 Michael Morrissey, “The Kid Makes His Pitch,” New York Post, September 11, 2004.

53 Eric Pfahler, “Gary Carter currently has no job offer from Mets organization,” TCPalm.com, December 14, 2006.

54 Adam Rubin and Nicholas Hirshon, “Gary Carter thinks he was missing piece for Mets in 2007 collapse,” New York Daily News, February 20, 2008.

55 Adam Rubin, “Gary Carter would love to take Shea reins as Mets manager,” New York Daily News, May 23, 2008.

Full Name

Gary Edmund Carter

Born

April 8, 1954 at Culver City, CA (USA)

Died

February 16, 2012 at West Palm Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.