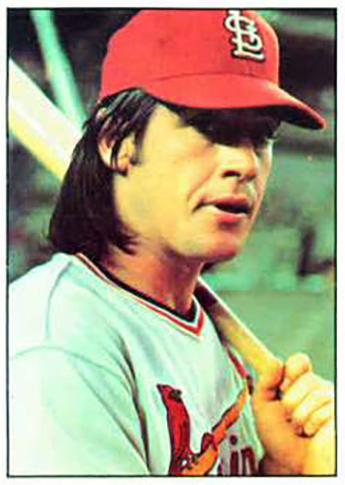

Ted Simmons

He was an eight-time All-Star, batted .300-plus seven times, and upon his retirement after the 1988 season, held the major-league record for hits (2,472) and doubles (483) by a catcher, to go along with 248 home runs and 1,389 RBIs. In December 2019, 25 years after receiving only 3.7% of the vote in his first year of eligibility for baseball’s Hall of Fame and being dropped from the ballot, he was elected by the Modern Baseball Era Committee to be enshrined in Cooperstown.1 His name was Ted Simmons.

He was an eight-time All-Star, batted .300-plus seven times, and upon his retirement after the 1988 season, held the major-league record for hits (2,472) and doubles (483) by a catcher, to go along with 248 home runs and 1,389 RBIs. In December 2019, 25 years after receiving only 3.7% of the vote in his first year of eligibility for baseball’s Hall of Fame and being dropped from the ballot, he was elected by the Modern Baseball Era Committee to be enshrined in Cooperstown.1 His name was Ted Simmons.

Ted Lyle Simmons was born on August 9, 1949, in Highland Park, Michigan, the last of four children of William “Bill” Finis and Bonnie Sue (Webb) Simmons. He grew up in Southfield, a suburb on Detroit’s northwest side, where his father’s job as a trainer for harness-racing horses afforded the family a stable middle-class, no-frills lifestyle. An athletic youngster, the right-handed-throwing, yet natural left-handed-hitting Ted began playing organized Little League ball by the time he was 9 years old at East Southfield school. His two brothers played an instrumental role in shaping his development. Jim, 15 years older than Ted, encouraged his sibling to begin switch-hitting by the age of 13 [“(He’d) whistle Wiffle Balls at me from 30 feet away,” remembered Simmons2; while brother Ned also spent hours practicing the fundamentals of the game with him.

The teenage Ted emerged at Southfield High School as one of the best all-around athletes in the Detroit metropolitan area. Standing about 6-feet-1 and weighing 175 pounds, Ted was quick, sinewy strong, and agile, athletic traits that enabled him to excel on the hardwood court and especially the gridiron, where he was a star halfback. He scored 14 and 15 touchdowns in his junior and senior seasons respectively, and was named to the Detroit-Area All-Star team and Third Team All-State in his final season.3 He was heavily recruited and purportedly received scholarship offers to play football at the University of Michigan, Ohio State University, Purdue University, and the University of Colorado, among others. Baseball, however, was his passion. His baseball and football coach, Ed Bryant, called him the “best athlete I have ever seen.”4

Big-league scouts were hot on Simmons’s trail by the time he was a high-school junior. Especially interested was scout Louis D’Annunzio of the hometown Tigers, for whom he worked out as a 16-year-old in 1966 in Tiger Stadium and participated in summer clinics. After his junior year, Simmons helped lead the A&B Brokers to the title in the Class D Detroit Amateur Baseball Federation5 and then to the National Amateur Baseball Federation Championship.6 Local sportswriter Hal Schram noted that the switch-hitting catcher drew 8 to 10 scouts every time he played in his senior year, when he batted .490.7 Widely anticipated to be a first-round selection in 1967, the still 17-year-old made it known that he’d prefer to fulfill his dream of playing baseball than signing a letter of intent to play baseball at the University of Michigan; however, he also expected a hefty bonus from a big-league team. Just days before he graduated, Simmons was chosen by the St. Louis Cardinals on scout Mo Mozzali’s recommendation with their first pick, and 10th overall, in the first round. According to St. Louis sportswriter Neal Russo, Simmons was initially disappointed that the Redbirds chose him because they already had 25-year-old All-Star Tim McCarver behind the plate, but a $50,000 bonus helped influence his decision to sign a few days later.8

“When I came to the rookie camp in Sarasota, I was 17, hot, and cocky,” recalled Simmons of beginning his professional career with the Cardinals’ rookie-level Gulf Coast League in mid-July.9 The brash youngster was introduced to the “Cardinal Way” by longtime minor-league instructor George Kissell, who “helped me grow up,” said Simmons, and he learned not just the fundamentals from the Redbirds lifer, but also “the ethical part of the game.”10 Simmons spent the bulk of the summer with Cedar Rapids in the Class-A Midwest League, where he hit .269 in 47 games. He also picked up the habit of smoking, which he continued for the rest of his career. “We took long bus rides. … (T)here was a lot of time on your hands with nothing to do,” he once offered as explanation.11

Simmons attended college at the University of Michigan in the offseason and his school requirements limited him to only a few days of spring training in the Cardinals’ minor-league camp in 1968. Back in Class A, Simmons tore up the California League with Modesto, leading the circuit with a .331 batting average and 119 RBIs, and was named the league’s MVP. In September he was back in Ann Arbor taking classes, but joined the big-league club on four weekends. He made his major-league debut on September 21, starting as catcher, and singling in his second at-bat against Claude Osteen of the Dodgers in Los Angeles.

After another abbreviated spring camp, Simmons was on the fast track to the majors and was assigned to Tulsa in the Triple-A American Association in 1969. As expected, he excelled with the bat, hitting .317 with 16 home runs and 88 RBIs and was named catcher on the Topps-American Association Triple-A All-Star Team. It was a different story while donning the tools of ignorance. “I was awkward,” admitted Simmons.12 He credited a minor-league coach and former Cardinals player from the 1930s, Mike Ryba, for helping him develop footwork, proper shifting, balance, and throwing techniques, but it was an arduous learning experience. Simmons made the most of another late-season look-see with the Redbirds. In his first start, on September 18 in St. Louis, Simmons laced a two-out run-scoring single to drive in Curt Flood for a dramatic 8-7 victory over the Pittsburgh Pirates. He provided the fireworks again two weeks later, belting a two-out triple to drive in Joe Torre for another walk-off victory, 6-5, against the Philadelphia Phillies.

After two consecutive pennants, the Cardinals dropped to fourth place in the NL East in the first year of divisional play, 1969, prompting GM Bing Devine to execute a blockbuster trade. He shipped McCarver, Flood, reliever Joe Hoerner, and journeyman Byron Browne to the Phillies for enigmatic and disgruntled star Richie Allen, Cookie Rojas, and Jerry Johnson in a transaction that altered the baseball landscape forever. (Flood refused to report the Phillies and subsequently challenged the legality of baseball’s reserve clause.) To make room for Allen, the Cardinals planned to move former catcher and regular first sacker in 1969 Joe Torre to third base and the veteran agreed to hone his skills at the Florida Instructional League that fall; however, the Cardinals’ master plan fell apart when Simmons was called for a six-month tour in the Army Reserve beginning in December.

Praised by GM Devine as “the most promising young (player) we’ve got,” Simmons missed all of spring training and was discharged in early May.13 He celebrated his freedom by marrying his high-school sweetheart, Maryanne Ellison, an art student at the University of Michigan, on his way to Triple-A Tulsa to get in shape. Simmons hit .373 in 51 at-bats and was promoted to the Cardinals at the end of the month. With the Cardinals struggling to play .500 ball, Simmons made his first start on May 30, and never looked back. On June 7 he belted the first of 248 career home runs, connecting off the San Diego Padres’ Roberto Rodriguez for a two-run shot in the Cardinals’ 10-7 victory at Busch Stadium. It was one of Simmons’s three hits to give him 10 in 18 at-bats in his last five games. “I finally feel I belong here,” he exclaimed. “I feel confident at the plate now.”14

But the transition to a full-time big-league spot was anything but smooth for Simmons. While the Cardinals (76-86) finished in fourth place with their worst record since 1959, Simmons seemed overwhelmed by big-league pitchers. His batting average plunged to .226 on September 16 before he caught fire, going 15-for-45 over his last 13 games to finish with a .243 average, but slugged an anemic .317 with three homers. Just 20 years old, he struggled at times behind the plate, allowing 15 passed balls (second-most in the NL) in just 74 games. “When I came up … I didn’t have time to know what a catcher does,” said Simmons.15

Thrust into the starting position without a chance to apprentice behind a veteran, Simmons needed help, and the Cardinals provided it with former Redbird All-Star catcher Hal Smith, who served as Simmons’s personal tutor, instructing him on basic fundamentals, strengthening his arm on throws to first and second, and developing better balance and agility.16

In 1971 Simmons finally participated in his first full spring training, in St. Petersburg. GM Devine preached patience with the 21-year-old and thought the club could “make allowances for his inexperience.”17 In addition to Simmons’s defensive learning curve, there were also questions whether he could hit big-league pitching. He himself wondered if he should continue switch-hitting, given his feeble .167 batting average as a right-hander (compared with .269 batting left-handed). “I almost quit,” he said. “[Hitting coach] Kenny Boyer and Red Schoendienst saw something in my swing and told me that I’d eventually come [around].”18 He worked with Boyer and Bob Kennedy, the team’s director of minor-league operations, to improve the strength of his left hand, which controls the bat when hitting right-handed. His regimen over the next several seasons paid off handsomely, though he admitted that he “put less control and more aggression” into his swing from the right side.19

Obsessively driven to improve all aspects of his game, Simmons emerged as one of baseball’s biggest early-season surprises in 1971. He started 16 of the first 17 games of the season, batted .396 and drew 10 walks. “By not crouching too much, I’m able to open up more,” said Simmons about his carry-over success from the previous campaign. “I’m not tying myself up at the plate.”20 He finished the campaign with a .304 batting average and 77 RBIs, both of which were second-best among catchers in the majors behind the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Manny Sanguillen. Led by Simmons and ’71 NL MVP Torre, the Cardinals made a run at the eventual NL East champion Pirates, coming as close as 3½ games on August 15, but finished runner-up. The day before, Simmons called Bob Gibson’s first and only big-league no-hitter, an 11-0 shellacking of the Bucs at Three Rivers Stadium; Simmons belted four hits and scored three times, culminating a torrid nine-game streak when he collected 17 hits in 38 at-bats.

Labor strife racked baseball in 1972 and in no city was the tension between players and management more pronounced than in St. Louis – and Ted Simmons was in the middle of it. While Curt Flood waited for his case to be heard by the US Supreme Court, five Cardinals refused to sign contracts in an ugly standoff that played out over the summer in the newspapers, as team owner Gussie Busch became increasingly disillusioned with player salary demands and what he considered insubordination. The first casualty was Steve Carlton, a 20-game winner in ’71, who was shipped to the Phillies on February 25; four others, Torre, Simmons, 14-game winner Jerry Reuss, and utilityman Bob Burda refused to report to camp. While Torre eventually signed a lucrative two-year deal, Devine invoked the renewal clause on the other three players. “Signed may not be the word,” said a statement issued by a Cardinals spokesman, “but they are under contract.”21

Reuss and Burda were ultimately traded, leaving Simmons the last man standing. And he kept standing. This was transpiring as the Major League Baseball Players Association, led by Marvin Miller, voted to strike less than a week before Opening Day. In the first work stoppage in big-league history, 86 games over 13 days were canceled and not made up. When the season started, Simmons was widely described as the first known player to play without signing a contract.22 While Busch dug in (“Let ’em strike,” he said famously, “I won’t give then one more cent.”23), Simmons articulated his principled stance. “I’m not a crusader,” he said. “I don’t even have a lawyer. All I want is more money.”24 He freely admitted that the Cardinals had treated him well and even offered him a raise of $7,500 to $25,000; however, he wanted $35,000 and later reduced his demand to $30,000, but Busch and Devine stood pat.

In the meantime, the season started, but save for a hot streak in June and early July, the Cardinals (75-81) were a lackluster fourth-place team. Their biggest offensive weapon was Simmons, who set a team record for home runs (16), RBIs (96), and hits (180) as a catcher, and batted .303. As the summer wore on and Simmons refused to accept the Cardinals’ contract offer, St. Louis sportswriter Bob Broeg noted that “sympathy is with Simmons” as the Cardinals endured a public-relations nightmare.25

When the Supreme Court rejected Flood’s case for free agency on June 19, widespread speculation emerged that Simmons would sue baseball. One day before Simmons was to participate in his first All-Star Game (he was chosen as a backup and did not see action), he signed a two-year deal reported to be for $70,000 on July 24.26 Devine attempted to save face by claiming that Busch had wanted the club to operate within the spirit of President Nixon’s wage-price guidelines, and had waited until the US Pay Board announced that professional athletes were exempt from wage control before they addressed Simmons’s demands.27

Simmons’s 10 full seasons with the Cardinals (1971-1980) read like a broken record: He was regularly the team’s most dangerous offensive weapon, leading it in home runs five times (and the runner-up three times) while the team finished last or next to last in the league in round-trippers six times; he led the Cardinals in RBIs seven times (runner-up two times), batted .300-plus six times and earned six All-Star berths.

Described by teammate Joe Torre as “about as strong a human as I’ve ever seen,” Simmons was remarkably durable.28 He caught an average of 135 games per season over that 10-year stretch, more than any catcher in the big leagues, and led the NL in games played as a catcher three times.

Simmons’s reputation as one of the best catchers of his generation has suffered because he played at the same time as three of the most prolific and most beloved catchers in baseball history: Johnny Bench, Carlton Fisk, and Thurman Munson (and a fourth beginning in 1975, Gary Carter). Nonetheless, during that 10-year stretch, Simmons collected more hits (1,631) than anyone in baseball except for Rod Carew, Pete Rose, Al Oliver, and Steve Garvey; drove in more runs (902) than anyone but Reggie Jackson, Bench, and Tony Perez. He hit for a higher average (.301) than any of the aforementioned catchers and finished second in round-trippers (169) among them, though well behind Bench’s 269.

Two factors have contributed to Simmons’s relative inconspicuousness compared with those players. He was never able to shed the impression that he was average or even below average defensively. He led the NL in passed balls three times, including a record-tying 28 in 1975 (which was still tied as of 2019 for the most since the beginning of the twentieth century) and finished second four times. He allowed the most stolen bases four times and was runner-up two more times.29 SABR member Bill Deane has suggested that such “counting statistics” misrepresent Simmons defensively, and offered a detailed analysis that Simmons was a slightly better than average defensive catcher.30 In an exhaustive essay focusing on modern sabermetric analysis, Chris Bodig argues that Simmons was indeed a below-average defensive catcher, ranking 65th of 70 catchers with at least 4,800 plate appearances and at least 50% of their games played as catcher.31

“It takes a long time for a catcher to get established,” said Simmons’s former teammate Tim McCarver in a 1978 interview with Ron Fimrite of Sports Illustrated. “We’re a different breed. But Teddy is thinking like a catcher now, and that’s what it takes. He has everything else. He’s the toughest guy behind the plate since John Roseboro, and he has terrific stamina. Sometimes I think the Cardinals are trying to kill him, catching him in all those games in that St. Louis heat. If they caught him 130 games instead of 150, he’d hit .360.”32

Secondly, unlike Bench, Munson, and Fisk, who combined to play for eight pennant winners and four World Series champions in that stretch (1971-1980), Simmons toiled for Cardinals teams that were generally average clubs. The Redbirds finished as high as second place three times (all within Simmons’s first four seasons) and also finished with a losing record four times.

As the funky ’70s heated up, free-spirited Simmons began to wear his hair longer and gradually acquired the moniker Simba for his collar-length mane of brown hair. Simmons was also called Sleepy for his laid-back, droopy-eyed appearance. Notwithstanding that easygoing, nonchalant façade, Simmons was an intense, alert competitor with a killer instinct and occasional combative temper, who often spoke of the emotional toll that losing and slumping had on his life and even family. “Winning. Winning. That’s what I want. I’ve done all the things except one,” he said as a Cardinal.33

Sportswriter Dick Wagner of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat opined in an exposé from 1980 that Simmons didn’t “fit the glamorous and golden image of a pro athlete” and never cared much for what others thought about him.34 According to Wagner, Simmons was a free-thinker who preferred leather jackets, boots, and motorcycles over coats and ties. “Most of what comes out of his mouth you will never hear from most players who perhaps are not capable of or willing to rise above the jock stereotype,” wrote Wagner.

Simmons’s best chance for the postseason with the Cardinals occurred in 1973 and 1974. After the Redbirds hit an NL-low 70 home runs in 1972, the club decided to install an artificial outfield fence that reduced center-field and power-alley depth by 10 feet and the height of the wall from 10½ feet to 8 feet in order to increase offense.35 The effect was negligible: The team finished last in the majors in home runs (75) and below the major-league average in scoring and hitting. The Redbirds got off to a horrendous start, lost 12 of their first 13 games, and were 8-23 on May 14. Simmons too slumped, batting .194 on May 11; both heated up, but the season seemed to be feast or famine. Over a 19-game stretch from June 25 to July 12, Simmons hit .387 (29-for-75) and knocked in 18 runs.

Ten days later, the Cardinals moved into an unlikely tie with the Chicago Cubs for first place after Simmons hit an eighth-inning two-run single and then scored the winning run in a 5-4 victory over the Dodgers. The Cardinals withstood an eight-game losing streak in August, but held onto first place until September 12 when only three games separated the Pirates, Cardinals. Expos, Mets, and Cubs in an abnormally weak NL East. Praised for his “high degree of maturity and tolerance to pain,” the 23-year-old Simmons surged down the stretch when the club needed him most.36 From August 24 to the end of the season, he was one of the hottest hitters in baseball, batting .384 (56-for-146), but his teammates bottomed out, at one point losing 13 of 17 in September to fall four games off the lead in the final week, and eventually finished runner-up despite a .500 record.

Simmons finished with a .310 batting average and cemented his reputation as one of the best switch-hitters in baseball (batting .310 left-handed and .311 right-handed). For the second straight season he finished fourth in the NL in hits (192) and third in doubles (36), and once again led the NL in defensive games by a catcher (153). He received the J.G. Spink Award as the St. Louis Baseball Man of the Year for the second consecutive year.37

In 1974 the Cardinals battled for the East crown, leading the division by as many as three games and never trailing by more than 3½. Simmons commenced the campaign with a 15-game hitting streak (he had a career-best 19-game streak the previous year and again in 1975), but the Motor City native was uncharacteristically inconsistent with the bat. On May 15 he broke his season-long homerless drought by spanking two round-trippers in one game for the first time in his career and driving in four runs in a 10-1 win over the Mets at Busch Stadium. Two days later he knocked in four runs against the Cubs in a 9-8 win in St. Louis, en route to winning the NL Player of the Week honor for the first of two times that season.38

From June through August he hit just .234, but the Redbird offense was sparked by a trio of .300-hitting outfielders, offseason acquisition Reggie Smith, Bake McBride, and 35-year-old Lou Brock, who swiped a record-setting 118 bases. Heating up down the stretch, Simmons’s 13th-inning sacrifice fly gave the Cardinals a 2-1 win over the Pirates on September 17 and extended their division lead to 2½ games. The team lost five of its next eight games; Simmons was instrumental in all three wins, spanking a decisive three-run home run in one, lacing a walk-off single in another, and whacking an RBI double to begin the scoring in the 11th inning in a wacky 13-12 win over the Pirates on September 25. Tied with the Pirates with two games to play, the Cardinals lost to the Montreal Expos, 3-2, in Canada, when Gibson yielded a soul-crushing two-run home run to Mike Jorgensen. The Redbirds finished 1½ games behind the Bucs and did not seriously challenge for the NL East crown again until 1982. Though his batting average slipped to .272, Simmons belted 20 home runs for the first of six times in his career, knocked in 103 runs, and remained one of the hitters most difficult to strike out in baseball, whiffing just 35 times in 662 plate appearances.

While the Cardinals were in the doldrums in the next six seasons (1975 to 1980), fielding three losing teams and not finishing higher than third. Simmons was a model of consistency and emerged as a vocal team leader. In 1975 he established career highs in batting average (.332, second-best in the NL) and hits (193), knocked in 100 runs, and finished sixth in MVP balloting. He was named the The Sporting News NL All-Star catcher for three consecutive campaigns (1977-1979), averaging 23 round-trippers and 87 RBIs. Duplicating his feat from 1972-1974, he was also named to the NL All-Star team three straight seasons (1977-1979), once as a starter, in 1978 when he collected his first hit in seven at-bats in the midsummer classic. En route to another Simmons-eque season (21-98-.303) in 1980, the 30-year-old catcher set a new record for most home runs as a switch-hitter in the NL, breaking Pete Rose’s record of 155.

Simmons’s 13-year stint with the Cardinals came to an unexpected end during baseball’s winter meetings in 1980, but the writing was already on the wall during Whitey Herzog’s 2½-month stint as interim skipper before moving into the front office as GM in August. Wanting to rebuild the team based on defense and speed, Herzog signed three-time All-Star Darrell Porter, who had been his catcher when he managed the Kansas City Royals. Objecting to a possible move to first base that would push All-Star, Gold Glove winner, and former MVP Keith Hernandez to the outfield, Simmons was the odd man out.

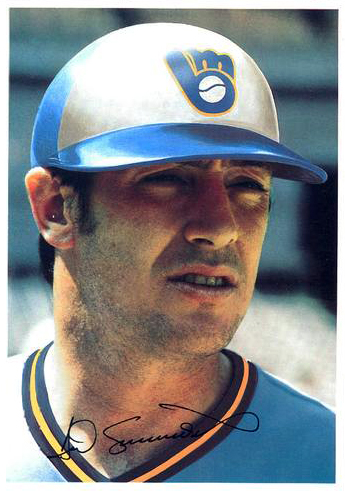

Just five days after Porter’s signing, the Cardinals executed one of the biggest blockbuster deals in club history, sending Simmons, perennial All-Star reliever Rollie Fingers (whom they had also acquired during the winter meetings in a stunning 12-player trade with the San Diego Padres), and right-hander Pete Vuckovich to the Milwaukee Brewers in exchange for workhorse right-hander Lary Sorensen, right fielder Sixto Lezcano, and two prospects, pitcher Dave LaPoint and outfielder David Green. Sportswriters tried to portray the trade as a rift between Simmons and Herzog, but the catcher flatly denied any controversy. Simmons had some leverage, though, as a 10-5 man (10 years in the majors and the last five with the same club) and had to agree to the trade, which he did when the Brewers paid him an estimated $750,000 to accept the deal. Herzog was vilified in the St. Louis press for jettisoning the fan favorite Simmons in a trade that seemed like a salary dump while receiving relatively little for three established players.

“It’s like a chance to start all over again,” said Simmons about the trade. “A new league, new town, training in Phoenix for the first time.”39 The Brewers (86-76), coming off a third-place finish, were expected to challenge the Baltimore Orioles and New York Yankees for the AL East crown. GM Harry Dalton considered Simmons an “unknown factor” in the competitive division, but anticipated that he’d strengthen an already explosive offense.40 The Brew Crew had led the majors with 203 home runs in 1980, paced by Ben Oglivie’s 41 homers, which tied Reggie Jackson for the AL lead, and the ’79 home-run champ, Gorman Thomas, who blasted 38 in 1980. “I feel like I belong in the American League,” gushed Simmons after blasting a two-run shot against the Cleveland Indians on April 12 in his second game as a Brewer. “I got my first hit, a long ball.”41

The 31-year-old catcher’s transition to the junior circuit, however, was anything but smooth. Bothered by a sore shoulder, Simmons struggled at the plate, batting as low as .190 on June 2. Ten days later, the players union went on strike in protest of several issues, chief of which was free-agent compensation. Known for his players’-first attitude, Simmons served as the team’s player representative to the union. After the cancellation of 713 games (38% of the season), play resumed on August 9 with owners having split the season into two halves. After a retroactive third-place finish (31-25) in the first half, the Brewers were declared AL East Division winners (31-22) in the second half, thus earning their first playoff berth in franchise history. Simmons (14 home runs, 61 RBIs) finished with the second lowest batting average (.216) among qualifiers though he earned his seventh All-Star selection. After losses to the Yankees in the first two games of the ALDS at home, the Brewers took Game Three, 5-3, at Yankee Stadium, behind Simmons’s two run-home home run and RBI double, but the Yankees took the series in five games.

The 31-year-old catcher’s transition to the junior circuit, however, was anything but smooth. Bothered by a sore shoulder, Simmons struggled at the plate, batting as low as .190 on June 2. Ten days later, the players union went on strike in protest of several issues, chief of which was free-agent compensation. Known for his players’-first attitude, Simmons served as the team’s player representative to the union. After the cancellation of 713 games (38% of the season), play resumed on August 9 with owners having split the season into two halves. After a retroactive third-place finish (31-25) in the first half, the Brewers were declared AL East Division winners (31-22) in the second half, thus earning their first playoff berth in franchise history. Simmons (14 home runs, 61 RBIs) finished with the second lowest batting average (.216) among qualifiers though he earned his seventh All-Star selection. After losses to the Yankees in the first two games of the ALDS at home, the Brewers took Game Three, 5-3, at Yankee Stadium, behind Simmons’s two run-home home run and RBI double, but the Yankees took the series in five games.

Simmons experienced his most frustrating and torturous season in 1982. Despite a monstrous game against the Minnesota Twins on May 2, matching his career high with two home runs for the seventh of eight times and six RBIs (achieved twice previously), Simmons began the campaign in a prolonged slump. By the end of May he was batting just .217, eliciting regular boos from Brewers faithful at County Stadium. Struggling to play .500 ball, the Brewers fired manager Buck Rodgers on June 2, leading to an acrimonious departure. Rodgers blamed two clubhouse “cancers” for the club’s problems. Though he didn’t mention names, it was widely understood that he meant Simmons, whose perceived defensive liabilities, offensive meltdown, and outspoken personality grated on the former backstop, and pitcher Mike Caldwell.42 Simmons responded by closing himself off from the press and not granting any interviews for the remainder of the season, and never publicly addressed the matter, stating only, “The whole thing was about my integrity.”43

The entire clubhouse atmosphere changed when longtime Brewers minor-league coach Harvey Kuenn was named skipper. His famous epithet, “Have some fun,” relaxed the players.44 They won 30 of their next 41 games, moving into a sole possession of first place on July 15; and extended their lead to a season-high 6½ games on August 27. Simmons heated up, too, collecting 16 hits in his last 35 at-bats and knocking in 11 runs in 9 games to push his batting average to .273 at the end of August. Leading the division by four games with five more to play, the Brewers lost four straight, the latter three to the Orioles, with whom they fell into a tie in an epic season-ending four-game series in Baltimore. In the winner-take-all game on Sunday, October 3, the Brewers bats exploded for 10 runs and four home runs, including two by Robin Yount, cementing his eventual MVP award, and one by Simmons, who finished with 23 home runs and 97 RBIs. “It was a very difficult time,” said Simmons, emphatically ending his self-imposed silence and reflecting on the turbulent season. “I figured the only way out of it was to win.”45

After losing two straight to the California Angels in the ALCS, the Brewers won three in a row at County Stadium to advance to their first World Series. It was a contrast in styles: Harvey’s Wallbangers, the major-league leaders in home runs (216) and runs scored (891), vs. Whitey Ball, a reincarnation of the Deadball Era game, stressing speed, stolen bases, small ball, and defense. The Brewers exploded for 10 runs in a Game One shutout on October 12 at Busch Stadium, which erupted in cheers each time their former favorite son, Simmons, came to bat. In the fifth, Simmons belted a solo shot off Bob Forsch. “I was geared to take the gamble that they would throw me a fastball down, and it was right there, he said.46 Simmons hit another solo shot in Game Two, but collected only one more hit in the final five games as the Cardinals won Game Seven in the Gateway City.

In 1983 Simmons split his time behind the plate and as the DH and responded by batting .308, knocking in a career-best 108 runs, and earning his final All-Star section while the Brewers won 87 games yet finished in fifth place in the division. On June 12 Simmons doubled in the 10th inning against the Yankees in County Stadium to reach to reach the 2,000-hit plateau. He parlayed his successful season into a lucrative three-year/$3 million contract.

The wear and tear of catching of 1,700-plus games caught up to Simmons quickly. His batting average dipped to .221 and he hit just four round-trippers in 497 at-bats in 1984 despite not donning the tools of ignorance. He rebounded slightly in 1985 (12-76-.273) as a DH and first baseman as the Brewers (71-91) bottomed out with a sixth-place finish.

Traded to the Atlanta Braves in March 1986, Simmons spent his final three seasons playing sparingly behind the plate and at first and third base. A graybeard on a struggling young team, Simmons was a de-facto playing coach, helping players adjust to the major leagues.

After 2,456 games, the 38-year-old Simmons retired after the 1988 season, but he did not stay away from baseball long. As he had for almost his entire playing career, he returned in the offseason to St. Louis, where he resided with his wife, Maryanne, and their two children. He accepted a job as the Cardinals’ director of players personnel and thus commenced a three-decade career as a baseball executive.

In 1992 he was named GM of the Pittsburgh Pirates, won the NL East crown in his first season, then presided over a grueling transitional period that saw the club lose reigning MVP Barry Bonds and former Cy Young Award winner Doug Drabek to free agency. A three-pack-a day cigarette smoker, Simmons suffered a heart attack on June 8, 1993, and resigned less than two weeks later after just 16 months on the job to concentrate on his health.47

Simmons returned to baseball again in 1993, taking a less strenuous position with the Cleveland Indians as a special-assignment scout. During his stint in that capacity, the Indians rose from perennial also-rans to one of the best teams in the AL, winning the pennant in 1995 and 1997. In late 1997 Simmons was hired by the San Diego Padres to serve as vice president of scouting and player development, a position he held until 2007.

Simmons was back in a baseball uniform in 2008, as bench coach for the Milwaukee Brewers, and served in the same capacity for the Padres in 2009-2010. In 2011 Simmons was hired by the Seattle Mariners as senior adviser to Seattle Mariners GM Jack Zduriencik, and remained in that post through the 2015 campaign.

Simmons was unquestionably one of the most productive hitting catchers in terms of cumulative as well as peak performance in major-league history. Upon retirement, he ranked eighth all-time in games caught (1,771; and ranked 16th as of the end of 2019); his 2,472 hits ranked second all-time as of 2019 behind Hall of Famer Ivan Rodriguez; and his 1,389 RBIs rank second to Yogi Berra, as of 2019. He hit .300-plus seven times, knocked in at least 90 runs eight times, and finished in the top 10 in each category five times from 1971 to 1980; six times in doubles, and three times in total hits.

Despite those statistics, Simmons received just 3.7% of the votes in his first year of eligibility for enshrinement in baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, in 1994, and was consequently purged from the list for failing to receive the required 5% of the votes. He was later included on two other “second chance” ballots; on the Veterans Committee in 2011, and the Expansion Era in 2014. In 2015 Simmons received a measure of atonement when the Cardinals inducted him into their Hall of Fame. He was also inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame (2005); the St. Louis Sports Hall of Fame (2010), and the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame (2012).

Simmons’s chances to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame greatly improved when he was added in 2017 to the ballot of 10 “Modern Baseball Era” players which the 16-member Veterans Committee decided. In his first year of eligibility Simmons received 11 votes, one vote shy of the required 75% for election, while Alan Trammell and Jack Morris were elected. Simmons’s 25-year wait for the Hall of Fame finally ended in December 2019. During baseball’s winter meetings, it was announced that Simmons received 13 of 16 votes by the committee and was thus elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, to be enshrined in a ceremony in July 2021. “There’s never too long a time to wait if you finally make the leap,” Simmons told St. Louis Post-Dispatch sportswriter Rick Hummel upon learning that the news. “And today I finally did.”48

As of 2020, Simmons still resided in suburban St. Louis with his wife, Maryanne.

Last revised: August 15, 2020 (ghw)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, Simmons’s Hall of Fame file, the online archives via Newspaper.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 AP, “Marvin Miller and Ted Simmons Elected to Baseball Hall of Fame,” New York Times, December 8, 2019. Simmons received 13 of the 16 votes cast; 12 were required for election by the Modern Era Committee.

2 Neal Russo, “Plate Specialist,” Everyday Magazine, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 14, 1971: 1.

3 Hal Schram, “1966 Free Press Detroit-Area All-Star Team,” Detroit Free Press, November 19, 1966: 14.

4 Hal Schram, “Meet a Prep Superstar,” Detroit Free Press, September 22, 1966: 1D.

5 “Tigers Draftee Star,” Detroit Free Press, August 8, 1966: 39.

6 Schram, “Meet a Prep Superstar.”

7 Hal Schram, “Southfield Draws All Baseball Scouts,” Detroit Free Press, May 10, 1967: 4-D; stats from Hal McCoy, “$$ or College? Prep Catcher Awaits Call,” Detroit Free Press, August 6, 1967: 4D.

8 Neal Russo, “Cards Pick a Winner – Workhorse Simmons,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1974: 3.

9 John Ferguson, “Cards’ Blue-Ribbon Prospect: Tulsa’s Catcher Ted Simmons,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1969: 35.

10 Ibid.

11 Dick Wagner, “This Man Isn’t What He Looks,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 28, 1980: 6B.

12 Neal Russo, “No Easy Rest for N.L. Hitters With Simmons Awake,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1970: 23.

13 Bob Broeg, “Shannon Is Out ‘Most of Year,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 18, 1970: 3E.

14 “Simmons Ready to Unpack Bags,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 8, 1970: 3C.

15 Jim Smith, “The Best Hitting Catcher in National League History,” Baseball Quarterly, Winter 1977: 40.

16 “Hal Smith Joins Cards as Ted Simmons’ Tutor,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1970: 12.

17 Bob Broeg, “Devine Flying Home on a Limb,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 26, 1971: 1B.

18 Smith.

19 Rick Hummel, “Simmons Became a Record Holder – And Didn’t Know It,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 3, 1980: 1H.

20 Neal Russo, “Simmons’ Bat a Pleasant Surprise to Cards,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1971: 15.

21 Joseph Durso, “Cards Invoke Reserve Clause on Two,” New York Times, March 8, 1972.

22 Bob Broeg, “Puppet Kuhn Can’t Pull Strings to Untangle Ted, Cards,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 27: 1972: 2C.

23 Ira Berkow, “Simmons Case: Cause Without a Rebel,” Poughkeepsie Journal, July 22, 1972: 13.

24 Ibid.

25 Bob Broeg, “The Simmons Case: A Touchy Issue,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1972: 4.

26 Dick Kaegel, “Simmons Is ‘Relieved’ With 2-Year Pact,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 25, 1972: 1C.

27 Ibid.

28 Russo, “Cards Pick a Winner – Workhorse Simmons.”

29 Earl Williams of the Atlanta Braves had 28 passed balls in 1972.

30 Bill Deane, “Simmons Deserves Better Break in Hall of Fame Balloting,” Baseball Magazine, October 1995: 13.

31 Chris Bodig, “Will Ted Simmons Ever Make the Hall of Fame,” Cooperstown Cred, August 9, 2018. https://cooperstowncred.com/will-ted-simmons-ever-make-hall-fame.

32 Ron Fimrite, “He’s Some Piece of Work,” Sports Illustrated, June 5, 1978. https://si.com/vault/1978/06/05/822710/hes-some-piece-of-work-cardinals-catcher-ted-simmons-is-a-collector-of-antiques-and-an-art-museum-trustee-but-none-of-his-old-treasures-is-as-masterfully-wrought-as-his-game.

33 Smith.

34 Wagner.

35 Bob Broeg, “Contrasting Cards’ Reactions to Shorter Fences at Busch,” The Sporting News, March 17, 1973: 36.

36 Bob Broeg, “’Losing Drives Me Crazy,” Says Simmons,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 20, 1973: 2B.

37 Simmons shared the award with teammate Lou Brock and St. Louis native Ken Holtzman, pitcher for the Oakland A’s.

38 Simmons won the award for the week of May 13-19 by going 13-for-24 with three home runs, 10 RBIs, and 9 runs; and then again for the week of September 2-8 with 10 hits in 22 at-bats, 5 doubles, 5 RBIs, and 5 runs.

39 Associated Press, “No Manager at Brewers Open Camp,” Manitowoc (Wisconsin) Herald-Times, March 1, 1981: 6.

40 Tom Flaherty, “Murder in Milwaukee,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1981: 3.

41 Tom Flaherty, “Slaton Wins It,” Milwaukee Journal, April 13, 1981: 13.

42 Steve Aschburner, “Simmons Talks Again,” Milwaukee Journal, October 4, 1982: 3.

43 Ibid.

44 Tom Flaherty, “Brewers Harvey, a Blast,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1982: 3.

45 Aschburner.

46 Dale Hofmann, “A Happy Homecoming for Simmons,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 13, 1983: part 2, 1.

47 Paul Meyer, “Players Stunned by Simmons’ Decisions, but Wish Him Well,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 21, 1993: B-3.

48 Rick Hummel, “After 25 years Cardinals catcher Simmons ‘makes the leap’ to Hall of Fame,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 9, 2019.

Full Name

Ted Lyle Simmons

Born

August 9, 1949 at Highland Park, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.