King Lear

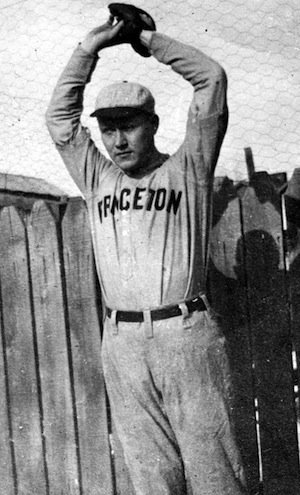

Charles Bernard Lear, a pioneering knuckleballer for the Cincinnati Reds, was born on January 23, 1891, in Greencastle, Pennsylvania. He was Frank and Mary Lear’s first-born child; his sister Mildred followed nine years later. Frank Lear worked in the metal trades, with his census professions indicated as moulder and tinner.

Charles Bernard Lear, a pioneering knuckleballer for the Cincinnati Reds, was born on January 23, 1891, in Greencastle, Pennsylvania. He was Frank and Mary Lear’s first-born child; his sister Mildred followed nine years later. Frank Lear worked in the metal trades, with his census professions indicated as moulder and tinner.

Greencastle, a small borough nestled within the Cumberland Valley not far from Gettysburg, provided a healthy baseball heritage for the boy. Frank Lear played in the 1880s alongside the hamlet’s first contribution to the majors: Bert Goetz, possessor of the “whip-poor-will swoop” – a colorful name for an ordinary curve, who pitched one game for the Baltimore Orioles in 1889.1 A decade later, Charles Pittinger ascended from the Greencastle lots to the majors, starring for the Boston Beaneaters and the Philadelphia Phillies. Young Charles Lear purchased his first baseball uniform from his hero Pittinger. Although Lear’s nickname was perhaps inevitable, Pittinger was also called “King” in south-central Pennsylvania. Perhaps local fans had more than just Shakespearean tragedy in mind when they bequeathed the handle to young Lear.2

After high school, Lear went on to nearby Mercersburg Academy, which had the “reputation of turning out one of the best preparatory school [baseball] teams in the East.”3 In 1910 his first season with the varsity, Mercersburg finished 19-0. Lear reportedly won 14 of these, including eight shutouts.4 In addition to prep and club teams, Mercersburg’s competition included freshman teams from regional collegiate powers Penn and Princeton. Lear shut out Penn on April 16, and pitched in relief when Mercersburg topped Princeton on May 20.

Duly impressed, Princeton recruited Lear, and he arrived on campus that fall. When the freshman baseball season arrived in the spring of 1911, he was a mainstay of its staff. But the freshman unit was a mild disappointment, finishing with a 6-5-1 mark, in part due to “erratic pitching.”5

Nonetheless, with graduation creating holes in the rotation, sophomore Lear figured to play a large role in the 1912 varsity season. Baseball was serious business at Princeton. Former major-league catcher Bill Clarke coached the Tigers and that spring, former major-league pitcher Carl Lundgren assisted him.

Under this tutelage, Lear emerged as one of the “best pitchers in the college ranks” that season.6 He shut out a strong Penn squad on ‘Straw Hat Day’ in early May, then lost narrow contests to Cornell (with President William Howard Taft in attendance) and Williams, before rebounding with a strong stretch that included victories over Harvard and Yale, bringing the Big Three championship to Princeton. When the season concluded, the Tigers were considered the best college team in the country, with the possible exception of the Williams College Ephs.7

Despite being at the core of such a squad, King Lear did not return to Princeton in 1913. Later in his life he claimed money as the reason. Contemporary reporting, and Coach Clarke, indicated “college conditions,” that is, some form of ineligibility, as the cause.8 It may well have been one and the same, if Lear had been discovered pitching for pay under an assumed name while at Princeton. As it was, his 1913 season indicated he was quite adept within the semipro circuits. He began with the Nassaus of Princeton in the spring, then put in brief appearances with Harrisburg and Chambersburg outfits in Pennsylvania, twirled for a Baltimore club, then concluded with a 15-3 stint for the Woodstock, Virginia, team.

That offseason, the Giants traded Buck Herzog to Cincinnati, where he was promptly appointed the Reds manager. Herzog was a Baltimore native, and financially backed the city’s semipro team that Lear had pitched for. Looking to build a stockpile of young arms for the coming 1914 season, Herzog signed Lear.9

Lear arrived at the Reds training camp in Alexandria, Louisiana, in late February 1914 as a lean (just under 6-feet, weighing 165 pounds) right-hander. He was a collegian in spirit, impressing teammates with his ability at billiards, and Southern belles with his dancing. Herzog saw a recruit with a serviceable curveball and a fastball that ran a bit. Then one day when he was warming up Lear himself, the manager recalled, the pitcher had mentioned another pitch. Years later, Lear recalled the moment: “Herzog said, ‘Let’s see that knuckle ball.’ I fired away, and he missed it. It bounced off his kneecap. Herzog then said, ‘If you don’t have any other pitch to throw, this will keep you in the league.’”10

The first two major-league knuckleballers of note came to prominence in 1908, with Eddie Cicotte joining the Red Sox staff and Ed Summers proving a rookie sensation with the Tigers. Cicotte’s pitch was reportedly held “on the three fingers of a closed hand, with his thumb and forefinger to guide it.”11 Summers’ pitch was “held between the lower thumb and the third finger, the index and second fingers being turned in much after the fashion of Cicotte’s hold.”12

Lear apparently threw the same pitch as Summers, stating in a 1915 interview that he used the “first and index fingers” to pinch the ball.13 (One’s first finger is usually referred to as one’s ‘index finger,’ or ‘forefinger.’ Thus it seems Lear was referring to his index finger and second finger. Modern fans can see the same grip in images of Tim Wakefield and R.A. Dickey holding a ball.) Lear reported first practicing the pitch in his Greencastle days, but seems to have used it sparingly until 1914; there is no mention of it in his Mercersburg, Princeton, and semipro career.

Lear survived the cut in the Reds training camp, and traveled north with the team for the start of the 1914 season. His debut came in the second game of the season, on April 17, when he pitched a scoreless top of the ninth against the visiting Chicago Cubs in a 6-5 loss. Lear continued to pitch well, in sporadic relief appearances in the early weeks of the season.

Cincinnati was off to a hot start. On June 3, at 26-17, the Reds stood in second place, a half-game behind the Giants. At this juncture, outfielder Armando Marsans argued with Herzog and was suspended by the manager. Without this valuable cog at the center of their offense, the Reds tumbled down the standings.

Lear remained mostly removed from action. But Reds business manager Frank Bancroft was fond of scheduling exhibition games (and barnstorming trips) and the rookie kept busy with shutouts of Toronto, Jamestown, and Toledo that summer. Finally, in the second game of a September 19 doubleheader at Brooklyn, Herzog gave Lear a starting assignment. The Reds had lost 14 games in a row, and occupied the cellar at 56-79. Lear lasted six innings and left with a 6-4 lead. Then Herzog sent in Phil Douglas, who surrendered four runs over the remaining two innings, and the Reds lost again.

Herzog handed Lear the ball again on September 23, again in the second game of a doubleheader. This time the Reds, their losing streak now at 19 games, were visiting the Boston Braves. These were the Miracle Braves, whose 1914 good fortune provided almost a reverse image of the Reds’ collapse. Pitching for Boston was George Davis, who had gained fame by no-hitting the Phillies two weeks earlier. Davis also, as an Eph, had bested Lear, in the major Williams-Princeton battle two seasons before.

“There was no logic, no sense, no possibility, according to all laws of anything, but base ball, in the way the game turned out,” wrote W.A. Phelon in The Sporting News. For, on this sweltering day, with the temperature hovering around 100 degrees, King Lear brought the Reds miserable streak to an end by shutting out the Braves, 3-0, on four hits. “The Reds’ least-known pitcher,” Phelon noted, showed “perfect control, beautiful speed, and a jumping hop that the Braves struck at like peevish monkeys.”14

Lear made two more starts in 1914, losing 7-4 to the Phillies on September 26, and losing 1-0 to the Pirates on October 3. He finished with a 1-2 record in 17 games (four starts). His 3.07 ERA and 1.329 WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) stood a bit over the league average. But with the promise of the last month, Phelon suggested it a “rather better than even bet that Lear of Princeton will be one of the big pitchers next season.”15 At another Alexandria spring training, Herzog reported Lear looking better than he had in 1914.

Yet Lear did not progress in 1915. He finished with a 6-10 record in 40 games (15 starts). His 3.01 ERA and 1.276 WHIP again were some 10 percent over the league average.

Lear’s sophomore difficulties began when all three major leagues moved to outlaw the emery ball, a scuffed-ball pitch made notorious by Russ Ford several years before. “This year,” observed Phelon in September 1915, “even the small cuts left by finger nails on the surface of the horsehide are enough to make any umpire chuck away the ball that may be in action, and Lear’s pet delivery has been nullified.”16

Without his floating, unpredictable knuckleball, Lear was a more ordinary major-league pitcher. The King also showed a propensity toward inopportune walks, and despite an off-the-field friendship with Herzog, their on-the-field relationship snapped after the last-place Reds were swept in a doubleheader by the Phillies on July 24. In the first game, in relief, Rube Benton issued two passes at the onset of the eighth inning. In the second Lear issued two passes to begin the first inning. The fiery Herzog suspended both pitchers. Four games later they were back, and Lear promptly put in an even worse performance, in relief, against the Braves.

Finally, in the last month of the season, with the Reds occasionally scrapping into the first division, Lear returned to promise. On September 10 he pitched a complete game 7-1 victory over the Cardinals, with Rogers Hornsby making his (0-for-2) major-league debut. Four days later, another complete-game victory came against the visiting Giants. But then, in Lear’s final appearance of the season, another leadoff walk in the eighth set in motion a 5-4 loss against the Cubs.

As the 1915 season drew to a close, the Reds reserved King Lear for the next season. But a torn ligament, apparently suffered in a postseason barnstorming trip that fall, made him expendable. Lear was released in December, and sold to the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. To replace the “unlucky Princeton man,” Phelon noted, the Reds had a “swarm of crack right-handers on the roster … to say nothing of what may come back from the Federal League.”17

Lear’s professional baseball career played out quickly. After several unimpressive weeks with Louisville in early 1916, he was released, signed by the Southern Association’s Atlanta Crackers, then two poor starts later released again. Lear then returned to Franklin County, Pennsylvania, pitching for Chambersburg of the Blue Ridge League. Several weeks later came another release.

Lear was pitching for the Newport, Pennsylvania, team of the Dauphin-Perry League in 1917 when he married Beryl Margaret Stafford, an Alexandria, Louisiana, native, on June 21. By the 1920 census, they were apart, and a decade later Lear was indicated as divorced. Lear worked in a number of professions after leaving baseball, including serving as Franklin County’s chief assessor. In 1929 he was granted a patent on an automobile heater. Throughout, he called Greencastle home.

After a lengthy illness, Lear died on October 31, 1976. He was buried in Greencastle’s Cedar Hill Cemetery.

Sources

I would like to thank Bonnie Shockey of the Allison-Antrim Museum and Ann Hull of the Franklin County [Pennsylvania] Historical Society for their assistance in obtaining materials related to King Lear’s life in Greencastle.

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Lear’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following sites:

Notes

1 On Goetz, see David Nemac’s entry in Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 230.

2 Several articles on Greencastle’s baseball history are available in The (Greencastle) Echo-Pilot, April 8, 1948.

3 “1913 vs. Mercersburg,” The Daily Princetonian,” May 20, 1910.

4 Tom Zullinger, “Lear Won Fame as School, College League Pitcher,” The (Greencastle) Echo-Pilot, April 8, 1948.

5 “Freshman Nine Fails to Fulfill Expectations,” The Daily Princetonian,” May 26, 1911.

6 “College Men in Big Games,” Boston Herald, May 6, 1912.

7 “College Sports in a Wonderful Year,” New York Tribune, December 29, 1912.

8 On his recollection: Tony Saitta, “Was Knuckleball Invented by Greencastle Pitcher,” Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, December 12, 1970; on Clarke’s take: “Sporting Notes,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, February 13, 1913.

9 Walter E. Hapgood, “James Wins – Then Reds Break Losing Streak at Davis’ Expense,” Boston Herald, September 24, 1914.

10 Saitta, “Knuckleball.”

11 Jim Sandoval, “Eddie Cicotte,” The Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/1f272b1a, accessed March 23, 2014.

12 “How Summers and Cicotte Pitch Knuckle Ball and Dry Spitter,” Indianapolis News, April 3, 1908.

13 Dixon Von Valkenberg, “ ‘King’ Lear and the Knuckle Ball – They Are Cincinnati Hopes,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, May 9, 1915. Note that in this interview Lear specifically did not claim to have invented the pitch. In his statements featured in the 1970 “Knuckleball” article (see endnote 7), he did claim to have done so. The 1915 statements seem more sustainable.

14 W.A. Phelon, “Reds Sure Upset All the Dope Pots,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1914, 2.

15 W.A. Phelon, “Another Week Gone and No Red Trades,” The Sporting News, January 7, 1915, 8.

16 W.A. Phelon, “Toney One Relief in Reds’ Failures,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1915, 2.

17 W.A. Phelon, “A Chance for Red Fans to Enthuse,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1915, 2.

Full Name

Charles Bernard Lear

Born

January 23, 1891 at Greencastle, PA (USA)

Died

October 31, 1976 at Waynesboro, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.