Valmy Thomas

In 1957, Valmy Thomas became the first man from the U.S. Virgin Islands to play in what were then classified as the major leagues. Since Thomas was born in Santurce, Puerto Rico, some gave Joe Christopher this honor, but it really belonged to Thomas — until December 2020, when the Negro Leagues were recognized as major leagues. As a result, Thomas’s good friend and teammate in Puerto Rico, Alfonso Gerard, gained additional honor for his pioneer effort as a Virgin Islander.

In 1957, Valmy Thomas became the first man from the U.S. Virgin Islands to play in what were then classified as the major leagues. Since Thomas was born in Santurce, Puerto Rico, some gave Joe Christopher this honor, but it really belonged to Thomas — until December 2020, when the Negro Leagues were recognized as major leagues. As a result, Thomas’s good friend and teammate in Puerto Rico, Alfonso Gerard, gained additional honor for his pioneer effort as a Virgin Islander.

Aside from reaching “The Show” two years earlier than Christopher, Thomas’s Puerto Rican birth was just a technicality. Quite simply, his mother sought better medical attention, and she returned home to St. Croix as soon as she delivered her baby. This man was a Crucian through and through — “the best place on earth,” he happily insisted.

On October 21, 1925, Valdemar and Clemencia Martin Thomas brought their third of six children (five boys and one girl) into the world. For many years, various later birthdates circulated. During his big-league career, Valmy’s baseball cards showed the year as 1929 or 1930; after that baseball references gave it as 1928. Upon his death in 2010, though, the true year became more widely known.1

Thomas grew up in the Water Gut neighborhood of St. Croix, about nine or ten years behind Alfonso Gerard. For eight years, they would be teammates with the Santurce Cangrejeros of the Puerto Rican Winter League. They were also opponents from time to time in the Dominican Republic and Canada. Older brother Alfred Thomas was a very close friend of Gerard’s. Alfred was not a ballplayer, but he was a supervisor in the Civilian Conservation Corps camp where Gerard, then a lefty pitcher, played in the 1930s.

As a youth, Thomas remembered the main sports being cricket (which adults like his father played) and soccer. His generation took to baseball, however; Valmy remembered cutting his own bats in the bush and using a tennis ball. He also recounted how older boys ran him and his friends off the field. “But we shortly retaliated,” he said with a grin. “There was no transportation, so you had to walk. And you had to pass a particular area, and we would have the stones piled up. We’d make sure not to throw at their heads, but they was hop-skipping-and-jumping!”

There were four local teams on St. Croix in those days. Along with the CCC camp squad, there were the Braves (Valmy’s neighborhood favorites), the Rangers, and the Senators, “a rough team. They had guys, don’t get between them and the bag, you get a broken leg!” One of the diamonds, now D.C. Canegata Ballpark, had a 13-foot slope, putting a premium on fast outfielders who could cut the ball off. Thomas was part of the crew that literally leveled the playing field.

Valmy spent 1943 to 1949 with the Navy in Puerto Rico (although he might have fibbed about his age to join, this too supports a 1925 birthdate). He learned about electronics and was part of the underwater demolition team, which disposed of bombs near Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, among other sites.2

During this period, Thomas played ball with local teams such as La Asociación Deportiva Parada 20 (Stop 20 Sporting Club — the trolleys identified the hub of Santurce). His strangest game experience came when he represented Puerto Rico in amateur competition in Cartagena, Colombia. Stationed in left field that day, he noticed that two Indians “with loincloths and hair matted down” had come down out of the hills and were observing by the fence.

“I had one eye on the ball and one eye on them,” he recalled, worried that an arrow might be whizzing his way. “The next inning, I saw them throw something over the fence. I could see where it was at, but I couldn’t see what it was. So when the inning was over, and I went to take a look, the track stars, they couldn’t catch me when I saw what that thing was — a snake! So I tell them, ‘You want a left fielder, you send somebody else, cause I ain’t goin’ out there!’”

Thomas was briefly on the roster of the San Juan Senadores in the winter of 1949-50, but he was Rookie of the Year in 1950-51 with Santurce, batting .302 under manager George Scales. The Crabbers won the Puerto Rican championship that year and four more times during Valmy’s 13 seasons with them: 1952-53, 1954-55, 1958-59, and 1961-62. As a result, Thomas played in five Caribbean Series, plus a sixth as a reinforcement with the Caguas Criollos in 1957-58.

Nearly 60 years later, one of the best-remembered games in the annals of the PRWL remains that of February 16, 1951. The Crabbers were facing Caguas in the seventh and deciding game of the championship series at old Sixto Escobar Stadium. José St. Clair, better known as Pepe Lucas, stroked a two-out, series-ending home run in the bottom of the ninth. The Dominican’s blow went down in history as the Pepelucazo.

Valmy recounted a previous incident involving him and Vic Power (known at home as Víctor Pellot) that indirectly influenced this dramatic outcome. In a play at the plate, Vic spiked Valmy in the hand. “When I was about to tag him, he jumped. Two guys asked me about it, was it an accident or did he mean to do it? They pulled out knives and showed me where they would stick them in him!

“Liquito Traboux was the other catcher. Pepe Lucas moved up one spot in the order to where I normally batted — not that I would have hit a homer!” Santurce went on to win the third annual Caribbean Series in Venezuela that year. It was the first of the three double winter titles for the club that also featured “Piggy” Gerard. Valmy recalled, “People took up a collection, but I didn’t want to go. I still have the mark there on my hand!”

In the summer of 1951, Thomas became another of the black players who went to Canada’s Provincial League. Canada had integrated earlier and was generally a much more receptive environment. Under a working agreement with the Pittsburgh Pirates, who owned his U.S. rights, he played for St. Jean, about 20 miles outside of Montreal. Although he performed well, going 9-48-.296 in 91 games, he left the club for economic reasons, even though it held up his progress to the majors. “Consider I played in Canada, making $400 a month, led the club in everything, played everywhere, and the next year Branch Rickey cut me $50. So what do you expect me to do? Bye!”

So Thomas “voluntarily retired” to protect his eligibility — but he actually played in the Dominican Republic from 1952-1954 (statistics remain unavailable). Pro ball had resumed there in 1951 but did not switch over to the winters until 1955.

“I go to Santo Domingo, play one game on Saturday, two games on Sunday, and I was making $1,100 a month.” Of that era, he recalled, “Trujillo, they didn’t tolerate no craziness there.” His first year, he played with Escogido, run by the Generalissimo’s brother-in-law, Paquito Martínez, but he then moved to Licey. Valmy remembered the rivalry between the two clubs and the intensity of fan emotions.

“To show you how they took their baseball, there would be a taxi driver. He is for the blue team [Licey]. This is his living. Do you know, if he sees a guy with the red cap [Escogido], he’s not going to pick him up? If the guy wants a ride, he takes his cap off and puts it away. We lived in a hotel, we looked out at a government sugar warehouse. At 5:00 in the morning they were struggling with these 200-pound bags to get the money for these three games on the weekend. They had bongo drums, they had si-renes. They was fanatics and they come to have a good time.”

Back with Santurce in the winters, Thomas became a part of two more double champions. On February 15, 1953, he had a big hit named after him too. The Tomatazo was a two-run triple in the 13th inning of Game Six of the finals versus San Juan.3 It sent the Crabbers to Cuba, where they beat the heavily favored Havana Reds in the Caribbean Series.4 The manager was another Negro Leaguer, Buster Clarkson.

Valmy split the catching duties with Harry Chiti on the truly outstanding 1954-55 squad, which Don Zimmer called “the best winter league baseball club ever assembled.”5 This time Herman Franks was the skipper. The cast of Latinos, Negro Leaguers, and both black and white major-leaguers featured an extraordinary outfield of Bob Thurman, Willie Mays, and Roberto Clemente. The staff was also strong; in particular, Thomas remembered handling Sam Jones, who won the Triple Crown of pitching that season. Jones had the guts to throw three straight curveballs after falling behind in the count 3-0 — in the ninth inning with the bases loaded. Working his trademark toothpick, glaring in, the meanest man Thomas ever played with would warn any batter who crowded the plate, “Motherf***er, cover it up!”

Another amusing anecdote from this period came about as the result of a losing streak. According to Valmy, owner Pedrín Zorrilla and coach Monchile Concepción were both fairly superstitious. So to get the hex lifted, they suggested going to a woman up in Valle Obrero who practiced santería. “I drove Alfonso Gerard, Willard Brown, Bob Thurman, and Johnny Davis up there. I said if you don’t believe, don’t come in this place. And we’re gathered around a table, and the lady lights a candle. Can you imagine, these big guys, six-foot-something and 200 pounds, holding hands and jumping around! And we went out the next day — and we got slaughtered!”

Valmy’s shot at the majors came courtesy of the friendly working relationship between New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham and Pedrín Zorrilla. In order for this to happen, though, he had to come back and play the 1955 season in St. Jean. (The absence of Dominican summer ball no doubt influenced his decision.) Then the Giants organization was able to draft him from the Pirates.

Valmy’s first stop was Minneapolis, where the frigid early-season weather disagreed with his Caribbean blood. “The first night, Eddie Stanky was making the lineup, and I told him ‘Don’t even look my way.’” After a game was snowed out, he told his roommate, future Cardinals star and NL president Bill White, “I think I have to be going south.” (He had kept enough money back to make the trip home.) When the GM said he was jeopardizing his chances of going to the big leagues, he replied, “I’m increasing my chances of pneumonia!”

Valmy wangled an assignment to the desert climes of Albuquerque, and on the strength of his .366 average there, the Giants wanted to call him up that fall. But he said, “I ain’t goin’ up to sit on no cold bench!” and went home to get ready for winter ball instead. He reached the majors the next spring, in 1957. In spring training, the unheralded invitee did everything well while names ahead of him on the depth chart got hurt.

He sealed his roster spot late in camp during a game against the Indians. Sam Lacy of the Washington Afro-American wrote, “In the second inning, he cupped a difficult, short hop peg from Willie Mays to nail Vic Wertz at the plate in a bang-bang play. In the fifth, the 160-pound Virgin Islander pulled Rubén] Gómez out of a ticklish, bases-full hole by picking Gene Woodling off first with a rifle shot throw to Gail Harris. Although Valmy is merely on loan from the Millers, Manager Bill Rigney said after the game: ‘If that’s the stuff to expect from this fellow, well — you just can’t tell.’”6

Valmy’s business sense remained sharp — as did his temper. “The year when I went up, the minimum salary was $6,000, but if you made the club, it was $7,500. On the cutdown day, Stoneham’s son-in-law, which was Chub Feeney [another future NL president], tried to pull a fast one. He was telling me, ‘We appreciate this and that, and we’re going to give you a raise.’ And when he brought out the contract, it was for $7,500. As if I’m so stupid that I don’t realize that’s no raise, that’s what he had to pay. And I cussed him out, I told him a few things. And I called Stoneham, and he came down, and he gave me a contract for $8,500. That’s the type of individual he was.” Thomas also remembered the owner allowing Willie Mays to fill in his own salary on a blank contract.

Shortly thereafter, the Virgin Islands Daily News announced that the territory had proclaimed Sunday, May 12, as Valmy Thomas Day.7 However, “he asked that formalities of the Day be postponed until he had proven himself under fire.”8 This he did on May 11 by hitting his first homer in the big leagues. It was a game-ending blow in the 15th inning at the Polo Grounds off Don Bessent of the archrival Brooklyn Dodgers. Another top sportswriter, Red Smith (then of the New York Herald-Tribune), provided more colorful detail. “A delegation of 15 Virgins from the Virgin Islands was shattering records for non-stop oratorical flight in tribute to their home grown catcher, Valmy Thomas. Thomas is a stubby half-bottle of muscle, the first ball player from the Virgin Islands to reach the big leagues. Aware that his countrymen had designated Valmy Thomas Day, he had cooperated with the committee in Saturday’s dank dusk.”9

That first season, as a semi-regular for New York, was Valmy’s best. He wound up starting more games than any other catcher for the Giants that year. Still another influential sportswriter, Leonard Koppett (then of the New York Post), found Valmy to be good copy. That July, Bill Rigney told Koppett, “I’d never seen him, all I knew was that Eddie Stanky at Minneapolis didn’t keep him. But I liked what I saw, and I like him now. He does a good job in calling pitches, mixes them up. He’s a good receiver, has a fine arm, and look how he hits. He’s got to be No. 1 as long as he’s all right.”10 When Thomas came home after the season, St. Croix finally held the long-promised island-wide holiday, pulling out all the stops with the welcome and ceremony.11

Thomas also saw a good bit of action for the first San Francisco Giants team in 1958, although rookie Bob Schmidt (whose injury had opened the door in 1957) became the starter. Valmy’s roommate during his first two years was another Caribbean, Bahamian cricketer turned shortstop André Rodgers, “who loved the bright lights of the city.” In December 1958, though, the Phillies obtained Thomas and Crabber batterymate Rubén Gómez for Jack Sanford. The deal looked logical but turned out poorly, as Sanford became a 24-game winner.

Although Thomas still played in 66 games for the ’59 Phillies, he spent most of 1960 and ’61 in the minors, though he did get time with the Orioles and Indians. (Around then he became one of the first blacks to play ball in Las Vegas, which was still partly segregated.) He was the only major-leaguer to play five years, each in a different city. His career totals: 12 homers, 60 RBI, and a .230 average in 626 at-bats over 252 games. An innovator, the backstop wore a light, flexible chest protector inside his uniform, even when he was at bat.

Valmy’s last year in the minors, 1962, was tumultuous. In just over two months, the feisty Crucian got into a volatile on-field argument and then became embroiled in a life-threatening love triangle.

Seventeen years later, future Royals manager Jim Frey told the story from his angle:

“Years ago, when I was playing in the International League, one of the umpires was Eddie Lopat’s brother. He was having trouble with the high pitch. He called two above the letters strikes on me, and I stepped out and said, ‘Look, you screwed me all last year on that pitch. It’s about time you learned it’s not a strike.’

“Lopat said, ‘Get back in and use that bat on the next pitch or I’ll call you out no matter where it is.’ Imagine that? Here was a guy telling me he was going to rob me. I said, ‘If you do, I’ll take this bat and beat you to death with it.’

Valmy Thomas was the catcher. He listened to all this.”

Later that game, Valmy was at bat.

“When the pitch came, and Valmy didn’t like it, he called him an S.O.B. Lopat threw him right out of the game.

“Valmy said, ‘How can you throw me out for calling you an S.O.B. and not throw out a man who has just threatened your life?’”12

The rhubarb escalated quickly. According to Ted Lopat, Thomas put both hands on the ump’s shoulders and pushed, then punched him on the chin and lip. Lopat’s two partners, Augie Guglielmo and Harry Shedd, had to restrain the catcher.

The next night, June 17, Jacksonville sold Thomas to Rochester (for whom he never played; he went on to the Atlanta Crackers). George Trautman, president of the minor leagues, suspended Valmy for 30 days. Lopat resigned in protest that the punishment was not stiff enough.

Then in Atlanta on August 21, Valmy was shot twice in the chest by a rival “who came in through the window — and it wasn’t even his house.” Sad to relate, mortician/musician Cleveland Lyons, 42, then took his own life.13

Although Valmy was in critical condition, he pulled through and put the unsavory sequence of events behind him. It was really rather remarkable that he played as much and as well as he did for Santurce that winter.

But to return to Frey’s account, the next time they saw each other, “[Thomas] runs up to me and grabs me by the throat and is screaming, ‘You dirty S.O.B., you almost got me killed! How’s that for logic?’”

Thomas wrapped up his Puerto Rican career in 1962-63. Over 14 years, he amassed 23 homers and 322 RBI while batting .255 (670 hits in 2,628 at-bats; the number of games he played is incomplete). He gave way to his understudy, future Oriole Elrod Hendricks. In later years, Ellie described Valmy as a formative influence on his early pro career.14

Valmy’s last games as an active pro came during the weekend of February 9-10, 1963. For many years, an annual exhibition series took place between Puerto Rican winter leaguers and a combined Virgin Islands team. That year the men of St. Croix and St. Thomas featured two other big-leaguers in Elmo Plaskett and Julio Navarro (a Puerto Rican who grew up on St. Croix) along with Hendricks and Thomas. In a surprise, they took two out of three from the Puerto Rican squad, starring Orlando Cepeda, José Tartabull, and Chico Ruiz (the latter two Cubans who were then playing with Santurce).15 As late as 1969, though, Valmy was still part of the V.I. roster.16

Although Thomas felt he could have played another year, he chose to come home to St. Croix and get more involved in local business and sporting affairs. He was a sports consultant with the Bureau of Recreation for six years, setting up many baseball events. Along with the series between the local pro-am teams and PRWL players, there were Red Sox-Yankees exhibition games in Frederiksted, and clinics with the likes of Hank Aaron and Lou Brock.

Valmy was also a boxing promoter during this time. In August 1965, he brought Muhammad Ali (then still known as Cassius Clay) to D.C. Canegata Park for an exhibition.17 In 1969, he engaged popular showmen from another sport, as the Harlem Globetrotters came to St. Croix and St. Thomas.18

Thomas became Deputy Commissioner of the Department of Conservation and Cultural Affairs on St. Croix, where he oversaw all recreational programs on the island. He was also a supporter of horseracing, serving as president of St. Croix’s Turf Club in the 1970s and ’80s. In addition, for many years he served as a sports commentator on local radio and TV.

For more than four decades, Thomas owned the United Sporting Goods store in Christiansted, although he eventually turned over management to his daughter Lisa. Lisa and Valmy Jr. were the two children of Valmy’s marriage to Lydia Nico. A prior union produced three other daughters: Shelley, Florence, and Juliette.

In the mid-1990s, Thomas ran for the Virgin Islands Senate, a curious 15-member body that is the only chamber of the local legislature. Though he finished back in the pack, he remained full of plans and ideas. Valmy always eagerly discussed the local business climate at length, and his knowledge of V.I. politics was incisive. As he listened to radio broadcasts of Senate votes, he could predict with 100% accuracy how each member would vote as the roll was called.

This twinkly-eyed white-haired gentleman often displayed a subtle, whimsical humor. His Caribbean accent gave his delivery an extra droll dimension. “Where is the foul line?” he demanded. “It does not exist. It is the fair line. I have been meaning to write to the Rules Committee. There are many things I must correct.”

In later life, diabetes and arthritis slowed down the old catcher. His health took a turn for the worse in the summer of 2010; after being confined to his bed, on October 16 “he died peacefully at home of multiple problems.”19 He was less than a week short of his 85th birthday. He was survived by nine grandchildren, 10 great-grandchildren, and even one great-great grandchild. He was interred in the Veterans Section of Kingshill Cemetery.20

For much of his time on earth, the Valmy Thomas lifestyle revolved around St. Croix’s outdoor pastimes: boating, fishing, and hunting. He remembered one particular tree fondly because decades ago, he dropped his gun and scrambled up it to avoid a feral pig! He had no use for the Information Age. As he said in 1999:

“I don’t want to clutter up my head. No way! Ain’t nothing goin’ into my head right now that I got no interest in. I am not a young person where I need to worry about such things. I am pretty well satisfied with whatever I do or don’t do. I get a computer, and I get hooked on this computer — pfft! I get hooked on my fishing line!”

Last revised: June 17, 2025

Acknowledgments

This biography originally appeared on the now-defunct website “Baseball in the Virgin Islands,” from which it was adapted.

Grateful acknowledgment to Valmy Thomas for providing his memories (personal interviews on St. Croix, 1999 and 2001, plus several phone conversations from 2000 to 2007).

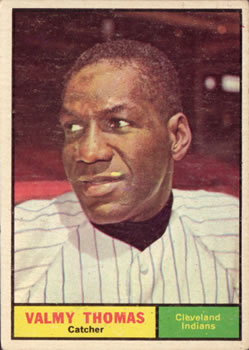

Photo credit: Valmy Thomas, Trading Card Database.

Sources

Valmy Thomas File at National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

Crescioni Benítez, José A. El Béisbol Profesional Boricua. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997.

Professional Baseball Player Database

Notes

1 Colón Delgado, Jorge. “Fallece Valmy Thomas.” El Nuevo Día (San Juan, Puerto Rico), October 23, 2010. The Social Security Death Index also shows 1925. So does a tribute delivered by the Honorable Donna M. Christensen (delegate from the U.S. Virgin Islands to the House of Representatives) on October 10, 2000. That tribute was drawn almost entirely from the original version of this biography. See Congressional Record, Volume 146, Part 15, October 6, 2000 to October 12, 2000.

2 Gray, Aaron. “V.I. baseball legend Thomas passes away at 81 [sic].” Virgin Islands Daily News, October 19, 2010.

3 Colón Delgado.

4 Van Hyning, Thomas E. The Santurce Crabbers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999: 41.

5 Van Hyning, 71.

6 Lacy, Sam. “Thomas thrills fans as Tribe clips Giants.” Washington Afro-American, April 13, 1957: 15.

7 “Day Set Aside to Honor Local Baseball Player.” Virgin Islands Daily News, April 23, 1957: 2. “Photos of Valmy Thomas on Display.” Virgin Islands Daily News, May 8, 1957: 1.

8 “Honoring Valmy Thomas.” Virgin Islands Daily News, September 3, 1957: 3.

9 Smith, Red. “[Johnny] Podres, [Pete] Burnside Remedies for Woes of Brooklyn Club.” New York Herald-Tribune, May 13, 1957.

10 Koppett, Leonard. “Valmy Thomas Is Surprising Everyone Pleasantly.” New York Post, July 22, 1957.

11 “Virgin Islands Honor Valmy Thomas Tues.” Virgin Islands Daily News, October 7, 1957: 3.

12 New York Daily News, October 8, 1979.

13 “Valmy Thomas, Ex-Giant, Shot.” United Press International, August 21, 1962. “Valmy Thomas Recovering From 2 Bullet Wounds.” Associated Press, August 22, 1962. “Atlanta Mourns Tragic Death Of Musician Lyons.” Jet, September 6, 1962. Among the four ministers who spoke at the last rites for Lyons were Martin Luther King Sr. and Jr., as well as Ralph Abernathy.

14 Hoose, Philip M. Necessities: Racial Barriers in American Sports. New York, NY: Random House, 1989. See also the biography of Elrod Hendricks by Rory Costello on the SABR BioProject.

15 “VI Stars Defeat Puerto Rico; Elmo, Elrod Blast Long Homers.” Virgin Islands Daily News, February 11, 1963: 1. “VI Stars Whip Puerto Rico; Take Two Out of Three.” Virgin Islands Daily News, February 13, 1963: 1. Al McBean of the Pittsburgh Pirates, a St. Thomas native, was at the opening game but not in uniform. Some reports said he was supposed to play, but others said he was never asked until the last minute.

16 “Major League Games Move To St. Croix.” Virgin Islands Daily News, February 15, 1969.

17 “Hundreds Attend Clay Exhibition.” Virgin Islands Daily News, August 4, 1965: 1.

18 “Globetrotters To Appear On Two Islands.” Virgin Islands Daily News, September 27, 1969.

19 Gray, op. cit.

20 St. Thomas Source, October 22, 2010.

Full Name

Valmy Thomas

Born

October 21, 1925 at Santurce, (P.R.)

Died

October 16, 2010 at Christiansted, St. Croix (V.I.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.