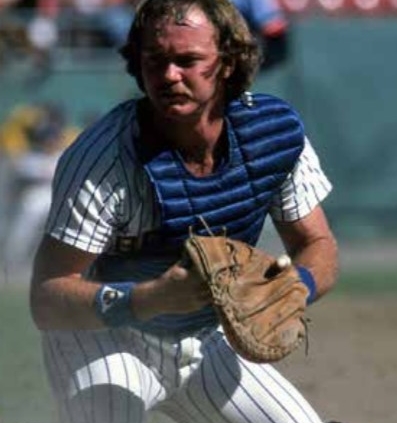

Charlie Moore

Charlie Moore played in the major leagues for 15 seasons, spending the first 14 with the Milwaukee Brewers and finishing up with a short stint with the Toronto Blue Jays. He is remembered as a key member the young Brewers teams that reached the American League playoffs in 1981 and the World Series in 1982.

Charlie Moore played in the major leagues for 15 seasons, spending the first 14 with the Milwaukee Brewers and finishing up with a short stint with the Toronto Blue Jays. He is remembered as a key member the young Brewers teams that reached the American League playoffs in 1981 and the World Series in 1982.

Charles William Moore Jr. was born on June 21, 1953, in Birmingham, Alabama, the son of a former minor-league baseball player. Charles Sr., pitched from 1949 to 1952, ending his career with the Evansville Braves of the Three-I League. He “hurt his elbow”1 and abruptly ended his career before his son was born. Because of his own injury he urged his son to become a catcher

Charlie Jr. had planned to attend Auburn University on a football scholarship after playing quarterback for Minor High School in Birmingham, but was drafted by the Brewers in the fifth round of the June 1971 amateur draft. “Dad preferred that I play baseball,” Moore said. “But he would have been happy with any decision I made.”2

Moore spent barely two years in the minors. Although his versatility was seen an asset from the start, he was used almost exclusively behind the plate in the minors.

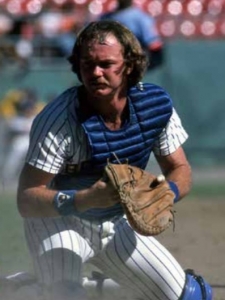

Moore played 1,334 games in the majors, all but 51 of them for the Brewers. He played most of them behind the plate and then fascinated many baseball fans by switching from catcher to right field in 1982.

He proved to be a competent outfielder, with 13 assists in his first year at the position, leading all right fielders in 1982 with six double plays and a .992 fielding percentage. He made a critical throw to third base to catch the California Angels’ Reggie Jackson as he tried to take two bases on a single in the fifth game of American League Championship Series.

After a September call-up for eight games in 1973, Moore was never sent back down. He made his major-league debut on September 8, 1973, during a 15-1 loss to the Yankees. Moore joined 21-year-old Darrell Porter, the Brewers’ first pick in the 1970 draft, and the presence of two promising young catchers allowed the team to trade Ellie Rodriguez to the California Angels.

Despite his rapid rise and acknowledged athletic abilities, Moore’s catching skills were still raw. “Our whole idea was to make him into an adequate catcher. That’s all we were hoping for,” said manager Buck Rodgers said years later. “We wanted to get his bat into the lineup for 80 or 85 games. He can do so much offensively — hit with men on, steal a base, go from first to third. He’s probably the fastest catcher in the major leagues. But Charlie’s done more than we hoped. He’s become better than adequate. He’s become an asset behind the plate.”3

As the backup to Porter, Moore played 72 games in 1974 (batting .245) and 73 games in 1975 (batting .290). In the winter of 1975 he joined fellow Brewers Jim Slaton and Kevin Kobel on the Dominican winter league champion Santiago team. “Moore played winter ball and improved tremendously,” said Brewers general manager Jim Baumer.4

Moore caught through August 1975, then played left field through May 1976, moved there to cover for injuries in the outfield. “Then, too, there is the fact that Charlie is hitting the ball,” said manager Del Crandall. “He has some speed and is an aggressive player.”5

The Brewers resisted trade offers for their pair of young catchers. Moore worked out at second base in the instructional league after the 1975 season. They were surprised by his outstanding play there as well as at catcher, third base, and right field.

In 1976 Moore batted a disappointing .191 with 3 home runs and 16 RBIs in 87 games, suffering through several minor injuries. New Brewers manager Alex Grammas benched him, sending him back to backing up Porter. Despite his difficulties, on October 3 at Milwaukee County Stadium, he was part of a historic moment as the last runner batted in by Hank Aaron, crossing the plate on Aaron’s sixth-inning single in the Brewers’ 5-2 loss to the Detroit Tigers.

The Brewers finished a disappointing 66-95 in 1976. Grammas had replaced Crandall as manager in 1976 with a reputation of being a better motivator of players, but his first season was rancorous and led to the exit of some veteran players. Porter was included in a trade to the Kansas City Royals with the promise that Moore was ready to become the full-time catcher, backed up by Larry Haney. Brewers pitcher Bill Travers opined after the deal, “Porter probably had more potential, but Charlie Moore called a better game. He mixed his calls a lot more. Darrell might have been afraid to call for my forkball when I had a good one going because he thought it would bounce off his glove.”6

After the 1976 season, Moore once again played winter ball, this time alongside Brewers teammates Jim Gantner and Tim Johnson with the Zulia club in Venezuela. As the team gathered for spring training in 1977, Moore was rewarded with a new two-year contract.

“You know when they asked me to sign at the end of last year,” said Moore, “I told them I’d wait and see what happens. If they had kept Darrell, I would have asked to be traded or played out my option.”7

The 1977 season was disappointing for the Brewers and unsettling for Moore, and cost Grammas his job. Moore caught in 137 games (116 as the starting catcher) and batted .248, an improvement over the previous year but far below expectations. On his way out the door, Grammas suggested that a change might be needed behind the plate, and Moore said he had the feeling “that I’m available for trade.”8 He said he was happy in Milwaukee, but he was not interested in going back to being a backup catcher.

He returned in 1978 to find that he was one of seven catchers on the Brewers spring-training roster. Harry Dalton, the new general manager, identified newly signed free agent Ray Fosse as number one. Besides Fosse, Moore had to contend with the others Dalton had assembled — Buck Martinez, Andy Etchebarren, Larry Haney, Ned Yost, and Ron Jacobs.

But Fosse’s time with the Brewers virtually ended during spring training when he tripped in a hole while running down the first-base line and injured his right leg. Reconstruction of a knee ligament forced him to miss the entire season.

Buck Martinez emerged as the starter, but in 1978 Moore hit better in a reserve role and new manager George Bamberger brought the team new magic as Bambi’s Bombers. The team finished third in a tough division with 93-69 record. Moore caught 95 games and began a successful professional relationship with newly arrived left-handed pitcher Mike Caldwell.

Although Moore was never identified as Caldwell’s personal catcher, they always seemed to form a battery in their years with the Brewers. They started 28 times together in 1978, Caldwell’s first year with the team, even though Moore had only 74 starts at catcher. In 1979 Moore caught 89 games and Caldwell was the starter in 30 of them. And in 29 of Moore’s 77 starts at catcher in 1980, Caldwell was the starting pitcher.9

In 1979 Moore, after signing another multiyear contract, shared considerable time behind the plate with Buck Martinez, with a few appearances by Fosse. His playing time and productivity had steadily increased, as he appeared in 138 games in 1977 (batting .248), 96 games in 1978 (batting .269), and 111 games in both 1979 and 1980 (batting .300 and .291). In 1979, he and Martinez were both hitting for high average with Moore peaking at .377 at midseason.

“A lot of people ask me, ‘Who is your number-one catcher?’” manager George Bamberger said in 1980. “I don’t have a number-one catcher. They are both number one.”10 Moore recovered from knee surgery for torn ligaments in the offseason and again shared time with Martinez in 1980. Remarkably, batting ninth on October 1, 1980, in a Brewers 10-7 win over the California Angels, he hit for the cycle and had two stolen bases in the same game.

Then GM Dalton made a deal for Ted Simmons (along with relief ace Rollie Fingers) before the 1981 season in a trade thought to establish the team firmly as a contender. Moore’s response endeared him to the Brewers fans: “I had always done what the organization told me to do. Whatever I can do to help the team win, that’s what I try to do, in whatever role they want me to play.”11 During the strike-shortened 1981 season, Moore played in 48 games, batting a career-high .301. In addition to 34 games behind the plate, he also appeared in the outfield and as designated hitter. And he played right field in the playoffs against the Yankees.

During the 1981 season the Brewers signed Moore to a new five-year contract that made him one of the highest-paid catchers in the majors. He had been eligible for free agency at the end of the season, the players strike was looming, and he faced an uncertain future backing up Simmons. Columnist Peter Gammons gave credit to Moore: “How many players can catch, play two outfield positions and third base, hit one-two in the order, run and hit .300? He’s more valuable than his physical skills which is why he is getting paid the way he is.”12

Even the new contract did not seem to be a guarantee of playing time, and there were reports that the Moore had asked to be traded, but by the end of spring training was assured that he had a clear shot at earning the starting job in right field. Moving him to the outfield in 1982 was a surprise to some, who expected Paul Molitor to finally find a permanent role there for the Brewers. Instead, Molitor eased Don Money into sharing time at designated hitter, and took over at third base.

The transition was not easy, and some joked that Moore seemed to be playing right field in self-defense. In spring training in 1982, he complained about his playing time. He suffered a muscle tear in his rib cage, preventing him from taking the field. “I was supposed to be given a shot in right field,” he said, “but as of now I’ve hardly played there.”13

Mark Brouhard was actually thought to be the right fielder at the end of spring training. Moore found himself platooning with Marshall Edwards and stressing at the plate. After hitting .283 in April, he slumped to .203 in May and .200 in June. Despite a boost to a .324 average in July, he got only 59 at-bats in August and hit .169.

In mid-August, Dalton and manager Harvey Kuenn met with Moore. “They told me they knew I was pressing, struggling, putting too much pressure on myself,” said Moore in October. “They said, ‘You have nothing to prove to us. You’ve done it in the past. You’re part of the club. We know you can play. Don’t worry about anything.’ That was the turning point. That helped me a lot. It took a lot off my mind.”14

Moore ended the season with a .254 average but was strong in September, hitting .308. Along with Robin Yount and Molitor, Moore showed speed on defense and the bases. By the end of the season he considered himself a right fielder. “People assume we’re like nine lumberjacks dragging our bats up there, and we take three swings trying to hit the ball out of the ballpark,” said Ted Simmons of the Brewers’ glory years. “We have our guys — Molitor, Yount, Moore and Jim Gantner — who can do a lot of interesting things.”15

While national television commentators debated his shift to the outfield during the 1982 playoffs and World Series, Moore was 6-for-13 (.462) in the American League Championship Series against the California Angels. Moore then hit .346 (9-for-26) with three doubles and two RBIs in the 1982 World Series, which the Brewers lost to the St Louis Cardinals in seven games.

Moore had perhaps his best season in 1983 when he had 605 plate appearances, by far the most in his career. Even after Simmons’s catching days virtually ended that season, Moore did not take a regular role behind the plate until 1985. He continue to play in right field during the next two seasons; in 1983 he played in a career-high 151 games, batting .284, but in 1984 he played in just 70 games while batting .234. He became part of a right-field platoon with Dion James, and went on the disabled list for the first time in his major-league career. By midseason James was playing everyday.

During his final two seasons with Milwaukee, Moore returned to catching, playing in 105 games and batting .232 in 1985, largely because of an injury to starter Bill Schroeder, and playing in 80 games and batting .260 in 1986.

In November 1986 Moore became a free agent. The Brewers had put him on the field for the ninth inning of the last home game of season so that he could get one final at-bat with the team. He was now among the rare players to have spent more than a decade with one team. Although Dalton advised him to pursue free agency, the Brewers offered him a one-year contract, but with a significant pay cut. Moore called the offer “disgusting and insulting.”16

Writer Peter Gammons recounted Moore’s frustration as his career ended as a Type-B free agent during the collusion era of 1987. No team had been willing to give up a first-round draft choice for a 33-year-old catcher. Gammons wrote, “Former Brewers catcher Charlie Moore knew that no major league team would sign him until after the June draft, when no compensation would be needed. So he hooked up with the San Jose Bees. The airplane ticket the Bees sent him put him the middle seat between two enormous women. After renting a car and driving to his first workout, he took the field and was immediately hit in the knee by a line drive. Informed that there was no trainer around, Moore drove to a 7-Eleven and bought five bags of ice for his knee. When he returned to the car, the battery was dead.”17

Moore eventually joined the Toronto Blue Jays. As a backup catcher for Ernie Whitt, he appeared in 51 games with the Blue Jays, batting .215 with one home run and seven RBIs. Toronto released him in November, bringing his career to a close.

In March 1988 Moore was one of the pallbearers — along with Gorman Thomas, Pete Vuckovich, Robin Yount, Paul Molitor, and Jim Gantner — at the funeral of the Brewers’ inspirational manager in 1982, Harvey Kuenn. Fans noted that Yount, Molitor, and Gantner were the only remaining players from the 1982 team on the Brewers spring-training roster.18

Moore and his wife, Lynn, lived in the Milwaukee suburb of Greendale in his playing days with the Brewers, but returned to Alabama with their three sons. For more than 15 years, Moore worked as a sales representative for a fastener company in Birmingham. His father and other members of his family were close by.

Fans warmly welcomed Moore when the 1982 team returned to Milwaukee in 2002 for a 20th-anniversary reunion.

In 2014 Moore was one of 58 Brewers inducted as a member of the Wall of Honor in Miller Park. He was one of three members of the All-Time Alabama Baseball Team in the group, along with Hank Aaron and Don Sutton. The Wall of Honor is open to Brewers who had at least 2,000 plate appearances, at least 1,000 innings pitched or 250 pitching appearances, won a major award, managed a pennant winner, earned induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame, or been honored with a statue outside Miller Park.19

Sources

In addition to the works cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball.Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the following:

Okrent, Dan. Nine Innings (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1985).

Schroeder, Bill, and Drew Olson, If These Walls Could Talk: Milwaukee Brewers (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2016).

Notes

1 “Moore Follows His Father in Solid Triplets Debut,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1973: 40.

2 Ibid.

3 “Face of the Franchise: 1983,” Brew Crew Ball, September 9, 2013, brewcrewball.com/2013/9/9/4710890/face-of-the-franchise-1983.

4 Lou Chapman “Pressure to Be Name of Brewer Game,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1975: 22.

5 Lou Chapman, “Moore Doing His Catching as Brewers’ New Outfielder,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1975: 19.

6 Lou Chapman, “Scott’s Exit to Aid Brewers — Travers,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1977: 33.

7 Lou Chapman, “Mitt Post Delights Brewers Moore,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1977: 40.

8 Lou Chapman, “Brewers Tap Vet Fosse to Help Young Hurlers,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1977: 57/62.

9 Michael Mavrogiannis, “Excruciating Baseball Lists — Personal Catchers,” members.tripod.com/bb_catchers/catchers/perscatch.htm.

10 Tom Flaherty, “Buck Is Settling in with Brewers,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1980: 21.

11 Brew Crew Ball.

12 Peter Gammons, “Goryl and Fregosi? Typical Fall Guys,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1981: 16.

13 UPI Archives, “Milwaukee Brewers Reserve Catcher Charlie Moore, Who Had Complained…,” March 25, 1982.

14 Tom Flaherty, “Moore Earning Brewer Praise,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1982: 25.

15 Doug Feldman, Whitey Herzog Builds a Winner: The St. Louis Cardinals 1978-1982 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2018), 191.

16 Associated Press, “Charlie Moore, Brewers Part Ways,” Green Bay Press-Gazette, December 8, 1986: B-10.

17 Peter Gammons, “Peter Gammon’s Midseason Baseball Report,” Sports Illustrated, July 20, 1987.

18 UPI Archives, “Former Milwaukee Brewers Manager Harvey Kuenn Was Remembered Thursday,” March 3, 1988.

19 Mark Inabinett, “Three State Baseball Greats Part of New Milwaukee Brewers Wall of Honor,” AL.com, June 14, 2014. al.com/sports/index.ssf/2014/06/three_state_baseball_greats_pa.html.

Full Name

Charles William Moore

Born

June 21, 1953 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.