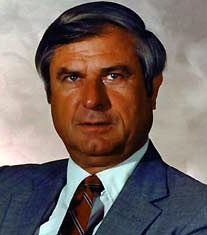

Harry Dalton

He was born Harry I. Dalton on August 23, 1928, in West Springfield, Massachusetts, the same hometown as Leo Durocher. He graduated as an English major from Amherst College in Amherst, Massachusetts. Historically, Amherst faced Williams in the world’s first intercollegiate baseball game in 1859. He had been accepted to the Columbia University School of Journalism, but was drafted into the military; Dalton joined the Air Force and fought in Korea where he earned a Bronze Star.

He was born Harry I. Dalton on August 23, 1928, in West Springfield, Massachusetts, the same hometown as Leo Durocher. He graduated as an English major from Amherst College in Amherst, Massachusetts. Historically, Amherst faced Williams in the world’s first intercollegiate baseball game in 1859. He had been accepted to the Columbia University School of Journalism, but was drafted into the military; Dalton joined the Air Force and fought in Korea where he earned a Bronze Star.

After leaving the military he had a brief stint as a sportswriter in Springfield. After the 1953 season, the St. Louis Browns franchise relocated to Baltimore. Coincidentally, Harry’s parents had moved there earlier, and in early 1954, while in Baltimore to visit his parents, Dalton phoned the Orioles and asked for an interview and was hired by scouting director Jim McLaughlin as a gofer in the Orioles organization. The job paid so little that Dalton had to drive a taxicab at night just to make ends meet.

McLaughlin was so impressed with the young man’s intelligence and work ethic that he moved him over to the baseball operations side to become his assistant. During his stint as farm assistant, Dalton was put in charge of the Birds’ minor-league spring camp in Thomasville, Georgia.

Just prior to the two major-league All-Star Games in 1960, he married Pat Booker on July 9, 1960. The couple had originally met on a blind date. They had three daughters – Kimberly (1962), Cynthia (1965), and Debbie (1967.)

Before the 1961 season, McLaughlin left the Orioles after a dispute with manager Paul Richards over the signing of pitcher Dave McNally. Ironically, Richards left the Orioles late in the 1961 season to accept the general managership of the expansion Houston Colt .45s.

General manager Lee MacPhail replaced McLaughlin with the 32-year-old Dalton, who assumed his new position on February 1, 1961. Dalton, having spent seven years under McLaughlin, had developed a reputation as a man with good baseball sense and a wonderful memory for names and maintained the work ethic which had first secured him the job. The Orioles farm system had been magnificently successful under McLaughlin so Dalton decided in the early days to maintain the status quo. Dalton later credited McLaughlin with training him well. That training led to a smooth transition from assistant to farm director.

Among the things Dalton did in his first year on the job was to name Cal Ripken, Sr., a 25-year-old catcher in the Orioles farm system, as player-manager of the Class D farm club at Leesburg, Florida. Ripken would manage the major-league team a quarter of a century later.

Dalton was very proud of his scouts and gave them a lot of credit for the success of the team’s minor-league system. In the minor-league draft of December 1962 the Orioles lost an astounding 18 players to other organizations. While disappointed in losing so many players, Dalton also noted that the losses were a credit to the scouts who had signed so many talented players. Dalton gave his scouts a lot of leeway in negotiating with potential signees. He asked only that they call him in the cases where a particular signee might require a large bonus.

During his nearly five years in the position of farm director, the Orioles produced such talent as Jim Palmer, Dave McNally, Boog Powell, and Dave Johnson.

In the autumn of 1965, new Commissioner of Major League Baseball Spike Eckert brought Oriole president and general manager Lee MacPhail aboard to assist him in baseball matters. MacPhail’s departure led to a reorganization of the Orioles’ front office. Chairman of the Board Jerry Hoffberger assumed MacPhail’s former role as team president with Frank Cashen assuming the executive vice presidency. Cashen was put in charge of improving the club’s public image and increasing ticket sales. While Dalton would be reporting to Cashen, Cashen was given no power in player moves. This power was vested entirely in the 37-year-old Dalton.

Dalton was named to replace MacPhail in his role as director of player personnel. At the time of his appointment, MacPhail had been working on a trade with the Reds to bring outfielder Frank Robinson into the fold. Dalton’s first move was to try and get an additional player out of the Reds.

In what is still considered one of the most lopsided trades in baseball history, Dalton obtained the future Hall of Famer for pitchers Milt Pappas and Jack Baldschun and minor-league outfielder Dick Simpson. The trade was finalized on Dalton’s third day in his new job. Robinson had recently reached his 30th birthday and the Reds were concerned that he was about to enter the downside of his career. As it turned out, nothing could have been further from the truth. All Robinson did in his first year in Baltimore was to win the American League Triple Crown and the league’s MVP award.

Dalton immediately divided the team’s minor-league operation into two separate arms. Lou Gorman was put in charge of player development while Walter Shannon was put in charge of scouting. Shannon had spent 27 years as a scout with the Cardinals during which he was involved in the signings of players such as Bob Gibson and Tim McCarver. Gorman was a minor-league general manager before Dalton hired him.

In 1966, Dalton’s first year at the helm, the Orioles, managed by Hank Bauer, won the American League pennant with a 97-63 record, finishing nine games ahead of the second-place Twins. As they were coming down the stretch, Dalton tried to make a trade for additional pitching but found the price was too high. Teams wanted some Triple A talent and Dalton was unwilling to mortgage the team’s future. It was the first pennant the team had won in their 13 seasons in Baltimore. The Orioles were led by the bat of Robinson, who won the league’s MVP award, and second-year pitcher Jim Palmer who led the team with 15 wins.

During their pennant-winning season, Dalton proposed cutting the major-league schedule from 162 games to 144. He cited three reasons for the proposal. One: fans feel the season is too long; two, players get tired and their performances suffer as a result; three: a shorter season would lengthen the career of most players. Dalton’s plan called for the season to begin in late April and run until mid-September. This, other league executives noted, would not help ease the problem of fatigue as the schedule would require the same number of trips. The proposal was not accepted, and the schedule remained at 162 games.

In 1967 the Orioles fell from the top of the league standings to sixth. This was due in part to a sore shoulder suffered by Jim Palmer that limited him to nine starts and a 3-1 record. The Orioles quickly proved the 1967 season was an anomaly by rising to a second-place finish in 1968.

After Bauer got the team off to a 43-37 record at the All-Star break in 1968, he was fired by Dalton. The firing took place less than two years after Bauer led the team to their first World Series title. He was replaced by Earl Weaver who had been a longtime manager in the Orioles chain. Weaver took the team to a second-place finish in the league.

In his first three full seasons at the helm, 1969-71, Weaver led the team not only to the AL East title but to the World Series as well. This was a great credit to Dalton who as farm director and director of player personnel had led the Orioles in their development of such players as Jim Palmer, Dave McNally, and Boog Powell. In those three seasons, the Orioles won one World Series (in 1970) and lost two. The World Series title led to Dalton being named Major League Executive of the Year for 1970.

In late October 1971, Dalton accepted an offer from Angels owner Gene Autry to leave Baltimore and become executive vice-president and general manager in Anaheim. The five-year deal, at a reported $60,000 per year, included stock options. Oriole President Jerry Hoffberger originally charged Autry with tampering for stealing Dalton away from Baltimore but later stated that he only asked Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to prevent teams from talking directly with personnel from another organization in the future.

One of Dalton’s first moves as Angels general manager was to swap longtime Angels shortstop Jim Fregosi to the Mets for four players, one of whom was future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan. The trade, which took place three months after Dalton assumed his new position, reaffirmed his reputation as a shrewd trader and a keen judge of talent.

Despite the emergence of Ryan as one of the American League’s best starting pitchers, Dalton was unable to duplicate the success he had had in Baltimore. In six seasons at the helm of the Angels he failed to produce a winning season and was never able to rise above fourth place in the AL West. At the end of the six years, Autry decided to replace Dalton with former Padres President Buzzie Bavasi. Autry announced that Dalton would remain with the Angels and left in charge of player trades and free agent negotiations while Bavasi would oversee baseball operations.

On November 21, 1977, Milwaukee Brewers president Bud Selig fired both GM Jim Baumer and field manager Alex Grammas. After receiving Autry’s permission to talk with Dalton, Selig hired Harry as his GM.

Dalton took over a Brewers team that had finished sixth in 1977 and had never had a winning season in the franchise’s nine-year history. But all was not bad. Four days before hiring Dalton, Selig had managed to lure defending AL RBI leader Larry Hisle from the Twins by signing him as a free agent.

Selig granted Dalton full power in all player moves. Coming to Milwaukee along with Dalton were Walter Shannon, Walter Youse, and Roy Poitevint. This group became known as Dalton’s Gang as they loyally followed him from Baltimore to the Angels and then to the Brewers.

With just weeks to go before the start of his first spring training in Milwaukee, Dalton named George Bamberger as his manager. Bamberger had been the pitching coach in Baltimore when Dalton was there and continued in that role until Dalton lured him away. Milwaukee was pitching-poor and Dalton valued Bamberger’s work in Baltimore.

It turned out to be a good move; the 1978 Brewers turned in the first winning season in franchise history going 93-69, good for third place in the AL East. They were spurred on by the emergence of Rookie of the Year candidate Paul Molitor and pitcher Mike Caldwell who won 22 games in ’78. Molitor finished second to Lou Whitaker in ROY voting.

The Brewers continued to win going into the early 1980s. In 1979 they won a franchise-record 95 games finishing second in the AL East – behind the Orioles. After posting a third-straight winning season in 1980 the Brewers made the first postseason appearance in franchise history in 1981. In that strike-ravaged season, the Brewers won the second-half title in the AL Eastern Division but lost the playoff to first-half champion New York Yankees. The Brewers were led by Cy Young Award-winning reliever Rollie Fingers, who also won the League’s MVP that year.

The Brewers entered the 1982 season with high hopes of winning a division title. The team got off to a slow start and manager Buck Rodgers found himself fired after a 23-24 start; he was replaced by hitting coach Harvey Kuenn, who took over the reins and led the team to their first-ever World Series appearance. They took it to the seventh game before losing to the Cardinals. Dalton’s accomplishment was recognized with his second Major League Executive of The Year honor.

Dalton was never able to return his team to that level of success, and team owner Bud Selig was forced to release him following the 1991 season. Selig replaced Dalton with assistant GM Sal Bando. Bando was hired in the hopes that his business acumen would help the financially-strapped franchise rebound. Dalton remained as a consultant in the team’s front office through the 1994 season at which time he retired.

Dalton’s contributions to the franchise were recognized when he was inducted into the Brewers Walk of Fame outside Miller Park in July of 2003. Dalton retired to Scottsdale, Arizona, and died there of complications from Lewy body disease, misdiagnosed as Parkinson’s disease, on October 23, 2005. Dalton was 77 years old.

Sources

Telephone interview with Pat Dalton, May 23, 2012.

Daniel Okrent, Nine Innings (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989)

The Sporting News, January 25, 1961.

The Sporting News, June 12, 1961.

The Sporting News, November 1, 1961.

The Sporting News, December 6, 1965.

The Sporting News, December 18, 1965.

The Sporting News, January 29, 1966.

The Sporting News, August 13, 1966.

The Sporting News, September 17, 1966.

The Sporting News, November 5, 1977.

The Sporting News, November 12, 1977.

The Sporting News, December 3, 1977.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Dalton

http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/BAL/1968-schedule-scores.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/BAL/

Full Name

Harry I. Dalton

Born

August 23, 1928 at West Springfield, MA (US)

Died

October 23, 2005 at Scottsdale, AZ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.