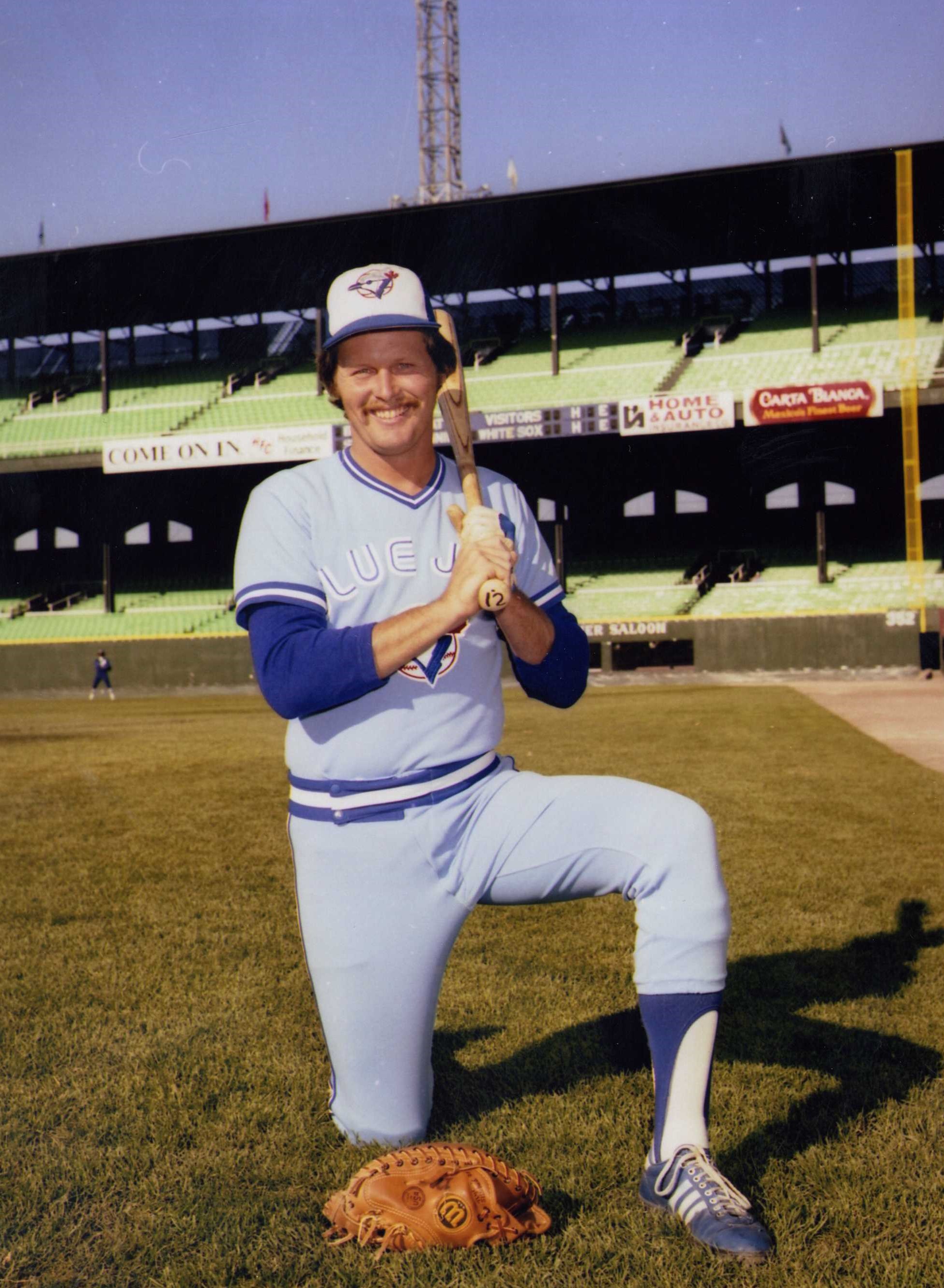

Ernie Whitt

On November 25, 2017, thousands of Canadians turned to the streets of Windsor, Ontario, for the annual Winter Fest Holiday Parade, and many went on that chilly Saturday to see Santa Claus ring in the holiday season. Others, though, were there to see someone even more popular in their eyes: Ernie Whitt, who served as the grand marshal. Ernie Whitt is synonymous with the early history of the Toronto Blue Jays. They grew up together. Whitt was selected in the expansion draft and through the 1980s was the solid rock behind the plate as the Blue Jays emerged into a pennant contender. He was there to guide the young pitching staff and provide eight straight seasons of double-digit home runs with his left-handed power. He was the last of the original Blue Jays, and after retiring as a player he remained in the game, coaching in the Blue Jays and Phillies farm systems and putting Team Canada on the baseball map. “We’re here, signing autographs and talking to people about the old days of baseball and the beauty of playing at Tiger Stadium, playing at Exhibition Stadium,” Whitt said. “Just talking baseball.”1 Even Santa couldn’t top that.

On November 25, 2017, thousands of Canadians turned to the streets of Windsor, Ontario, for the annual Winter Fest Holiday Parade, and many went on that chilly Saturday to see Santa Claus ring in the holiday season. Others, though, were there to see someone even more popular in their eyes: Ernie Whitt, who served as the grand marshal. Ernie Whitt is synonymous with the early history of the Toronto Blue Jays. They grew up together. Whitt was selected in the expansion draft and through the 1980s was the solid rock behind the plate as the Blue Jays emerged into a pennant contender. He was there to guide the young pitching staff and provide eight straight seasons of double-digit home runs with his left-handed power. He was the last of the original Blue Jays, and after retiring as a player he remained in the game, coaching in the Blue Jays and Phillies farm systems and putting Team Canada on the baseball map. “We’re here, signing autographs and talking to people about the old days of baseball and the beauty of playing at Tiger Stadium, playing at Exhibition Stadium,” Whitt said. “Just talking baseball.”1 Even Santa couldn’t top that.

Whitt grew up across the river in Detroit and became one of the most popular athletes in Canada. As of 2017, his 131 home runs as a Blue Jay ranked him 10th in team history, while his 19.2 WAR ranked him third. As of 2018, he was sixth (1,218) in games played. Bill James listed Whitt as the 72nd best catcher in baseball history in his New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract:

“Whitt was never a hot prospect, never caught many breaks, didn’t get a real look in the majors until he was 28, [and] didn’t get 300 at-bats in a season until he was past 30. But he worked hard, stayed in shape, just kept doing his best, and wound up having a pretty decent career.”2

Leo Ernest Whitt was born to Ernest and Dolly (Perrigan) Whitt on June 13, 1952, in Detroit, just a few blocks away from Tiger Stadium. Originally from the rolling hills of the Cumberland Gap in southwestern Virginia, Ernest and Dolly had relocated to Detroit in the early 1950s when Ernest sought work as a truck driver. The family, including brother Mike and sisters Melinda and Bernadine, often returned to visit the grandparents and take in the fresh air of farm life in Virginia. When Ernie was 3 years old, the family moved to a house in the Detroit suburb of Roseville. “The house looks pretty small now,” Whitt wrote in his autobiography, Catch: A Major League Life, in 1989. “But when I was a kid I thought it was huge.”3

Roseville had a lot of young families with children who loved the open spaces to play baseball. “In our backyard, there were two trees that made great first and third bases, and we could always find something to throw out for second. We’d play baseball all day, run in for dinner and run back out to play until we couldn’t see the ball anymore.”4

“I started playing baseball with the VFW post when I was seven years old,” Whitt remembered. They were supposed to be 8 years old, but brother Mike got Ernie in. “They needed a catcher and I basically lied and said I was a catcher,” he said with a chuckle. “From the earliest grades that I can remember, whenever some school form came around asking what I wanted to be when I grew up, I’d always write ‘professional baseball player.’” His Little League team often traveled to Tiger Stadium on Saturdays, where they saw stars Al Kaline, Norm Cash, and Willie Horton. Whitt’s hero was Tigers catcher Bill Freehan.5

In his teen years, Whitt grabbed his glove on Saturday mornings, jumped on a bus and headed for sandlots where professional baseball scouts held clinics. “Kids used to come from all over the city,” he remembered. “It was a bit of a madhouse and pretty hard to impress anyone. But if you were good and a particular scout liked the way you played, you would get invited back the next Saturday. I had one of their [Tigers] scouts following me. They told me they would draft me. They never did. I heard the general manager thought I’d never make it past Double-A ball.”6

Whitt was an all-state quarterback at Carl Brablec High School, and also played baseball and basketball. He had the opportunity to play football in college, but changed his mind after visits to Central Michigan and Eastern Michigan Universities. “I saw guys who were bigger than me and faster than me. I knew if they hit me, it would hurt,” Whitt joked.7 Ernie also played baseball in the Adray League, named for an appliance dealer who sponsored local youth athletics. “I’d always be at their tryout camps at Butzel Field and they’d always tell me, ‘You’re our boy. We’re gonna get you. Wait and see.’ They’d pick all-star teams to represent Detroit in a series in Canada, and all I’d think about was the Tigers signing me up.”8

After graduating from high school in 1970, Whitt enrolled at Macomb Community College in Warren, Michigan. “Playing at Macomb gave me an opportunity to play baseball and basketball,” he said. “It got me seen.” Major-league scouts had seen Whitt play, and Ernie hoped to be drafted in June 1971 after hitting .324 in his first season at Macomb. As no calls came, he continued at the school for another year, batting .333 with 32 RBIs and was voted the baseball team’s MVP and the college’s most outstanding athlete.

Whitt waited by the phone on June 6, 1972, as baseball’s amateur draft was taking place. “When the telephone rang, I said to myself, ‘This might be it,’” he recalled of those anxious moments. “It was, but it was the wrong team.” Whitt naturally hoped his hometown Tigers had selected him, but the voice on the other end belonged to Maurice DeLoof of the Boston Red Sox. “Would you like to play professional baseball?” DeLoof asked. “Are you kidding?” answered Whitt.9 The Red Sox drafted him in the 15th round for $2,500 and an allowance for college.

Whitt arrived in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, to join the Red Sox affiliate in the rookie-oriented New York-Pennsylvania League. Sam Mele, an instructor with the club, was impressed with Whitt’s hitting. After the 1972 floods postponed the season by a week. Ernie finally got into a game, playing first base, and collecting two hits. After the game, he was promoted to Winter Haven of the Class-A Florida State League.

Whitt had trouble adjusting to professional ball, as he batted only .183 in 31 games. Over the winter, Mele helped his swing in the Florida Instructional League, allowing him to bat .300. Ernie was promoted to Winston Salem of the Class-A Carolina League in 1973. He batted .290 in 130 games. In 1974 Whitt played for the Red Sox’ Double-A affiliate in Bristol, helping them win the Eastern League’s American Division title.

Ernie married Christine “Chris” Louise Jordan on June 19, 1974. Originally from Iowa, Christine met Ernie while visiting family in Michigan. The couple planned a fall wedding, but Ernie grew lonesome and suggested they marry during the season. The wedding was at 1:00 P.M. and Ernie was at the ballpark at 3:00. He went 2-for-3 in a 3-1 win. For the third consecutive year, Whitt returned to the Instructional League. Scouts were concerned that success would entice other scouts to select him in the Rule 5 Draft. “We don’t want anyone to see you,” Whitt was told. “We’re not going to protect you on a major-league roster, but we’re protecting you [in] Triple A and we’re inviting you to spring training next year.”10

Whitt was invited to the Red Sox’ spring camp in 1975 but was ultimately returned to Bristol. Things deteriorated when he separated his shoulder, requiring an operation, during a home-plate collision. “The runner charged in, crashed into me and ripped my left shoulder apart,” Whitt gruesomely recalled. “I could actually tilt my head and touch my ear to the bone sticking out. The Harvard doctor who looked at the tendons said it looked like an explosion in a meat factory.”11 Whitt was limited to 82 games at Bristol, where he batted .254 with only two home runs. However, during the postseason, Whitt laid down a squeeze bunt in the 17th inning of the deciding Game 3 to bring the Eastern League championship to Bristol.12

Frustrated by the numbers game, Whitt had to remain at Bristol for yet another year; he felt he deserved a shot at Triple A. “I went home and told Chris it was time to get out and get on with our lives. But she told me, ‘I’ve always said that I’d live in a paper bag with you. But I won’t live with you if you’re going to be miserable. You know you can play in the big leagues. You just have to hang on. With your talent, there’ll be an opportunity.”13

Whitt played 26 games at Bristol in 1976, before his opportunity at Triple-A Rhode Island (Pawtucket) presented itself. A roster spot opened when Andy Merchant was recalled to replace an injured Carlton Fisk. Whitt shared catching duties with Bo Diaz. “I don’t know what the organization’s got planned for you,” his new manager, Joe Morgan, stated honestly. “I don’t know whether you’ll go back to Double A when Fisk gets healthy or what. So I’m going to play you the way I think is best for this team, and you just have to go out and do the best you can.”14 Whitt had a strong season, batting .266 with 7 home runs in 90 games. Once Rhode Island’s season was over, Whitt was promoted to Boston. He made his major-league debut on September 12, 1976. With the Red Sox ahead, 11-3, over Cleveland, manager Don Zimmer sent Whitt to pinch-hit for Carlton Fisk. Whitt grounded out to second, then remained in the game to catch.

Whitt had a homecoming when the Red Sox had a two-game series in Detroit. In the opener, Whitt replaced Fisk behind the plate in the ninth inning of an 8-3 Boston win. Fisk approached him after the game. “You’re from this area, right? Go home and tell your family and friends that you are going to start tomorrow.” The kid from Detroit was starry-eyed as he made his first at bat that day. “When I came up to hit, Bill Freehan was behind the plate for the Tigers and said ‘Welcome to the big leagues.’”15 Whitt went 0-for-2 before being replaced by Bob Montgomery in a 5-4 win. Whitt’s first major-league hit was a solo home run off Milwaukee’s Jim Colborn that clanged off the right-field foul pole in a 3-1 loss on September 21.16 He finished the season batting .222 in eight games.

Boston left Whitt unprotected in the expansion draft, and he was selected by Toronto in the third round. But there were no guarantees of a spot on Toronto’s roster, since the team had three experienced catchers in Alan Ashby, Rick Cerone, and Phil Roof. “I was depressed for a while the first few weeks of training,” Whitt admitted to Bill Newell of the Hartford Courant, “but lately I’ve been feeling great because I’m getting some opportunities to play. The first game manager Roy] Hartsfield let me start I hit a home run and threw out five runners trying to steal. I think I made an impression that day, but, truthfully, I’m just not hitting.”17 On the final day of spring training, Whitt was sent to Charleston (West Virginia) of the International League, a Houston affiliate, because Toronto had no Triple-A team. “I was very disappointed I wasn’t on the club,” Whitt recalled.18

Whitt played in 29 games for Charleston and was recalled to Toronto at the end of May when Cerone was sent down. Ernie played in 23 games as Ashby’s backup, starting 10 and batting only .171, but achieved a flawless fielding percentage. He was frustrated at being used strictly as a pinch-hitter, not starting a game behind the plate until late June. “Actually I don’t have fond memories of those first few years in the Hartsfield regime,” Whitt admitted late in his career.19 Frustrations continued when his season was truncated in August after a home-plate collision with California’s Andy Etchebarren, resulting in a dislocated tendon in his foot.20

Whitt spent most of 1978 with Triple-A Syracuse. Since the Blue Jays focused on developing Pat Kelly as a catcher, Whitt spent 20 games at first and a handful of games in the outfield, batting .246 with 12 home runs. He was recalled to Toronto for only two games in September.

Whitt spent all of 1979 with Syracuse, earning a Silver Glove Award for being the best defensive catcher in the International League, but still didn’t seem to be in the Blue Jays’ plans for the future. “I don’t know why [Hartsfield] didn’t care for me. It was a frustrating year.”21 Again he contemplated quitting. He admonished Hartsfield: “I don’t think you can manage at the big-league level. You don’t know talent.” He asked Toronto GM Pat Gillick for a trade, which never happened. Chris once again motivated him to persevere: “You’re in Triple A. You’re one step away. You’ll never know if you quit now. You’ll go to bed every night and your head will hit the pillow and you’ll lay there and think, ‘I wonder if I could have made it if I’d just stayed in’”22

Time was on Whitt’s side, as he was now out of minor-league options. He had to be called up or placed on waivers. But Ernie’s perseverance paid off when Hartsfield was fired and replaced by Bobby Mattick as manager. Mattick had been impressed with Whitt’s 1979 season, even trading Cerone to open a spot on the major-league roster for him. The first day Mattick was appointed, he called Whitt to say he would be the Blue Jays’ starting catcher in 1980. “I’ve got to give [Mattick] credit for giving me the opportunity to play, and for sticking with me, when I was trying too hard,” Whitt said. He platooned with Bob Davis, sitting against lefties. Although he continued to be platooned, he remained with Toronto for the entire decade. He finally made it.

Ernie struggled at the plate (.237-6-34) in 1980 but had a decent .986 fielding percentage and was fifth among catchers in the AL in assists (56). His second-half batting (.254) overshadowed his first-half slumps (.204), and the team had its first season with fewer than 100 losses (95). Whitt upped his fielding percentage to .991 in 1981 and was second in assists in the strike-shortened season. On a cold, damp May night in Cleveland, Ernie got a call while in the bullpen. He wasn’t thrilled with the idea of pinch-hitting, but he trotted in to bat in the ninth inning. He flied out to center and was the last out of Len Barker’s perfect game. “There were a lot of bad feelings around here at the time,” Whitt said. “We were losing. We couldn’t score any runs. Everybody was down, and then we were out of a job.”23 But the Jays, 16-42 before the strike, showed some spark and finished 21-27 in the second half, while Whitt, batting .232 before the strike, batted .286 from September on.

New manager Bobby Cox came aboard in 1982 and the team played near-.500 ball (78-84). Whitt had breakout numbers at the plate (.261-11-42), including a 4-for-4 game against Milwaukee on August 3. His 11 home runs began an eight-year streak of double-digit home-run totals. The 1983 season saw continued success for both Whitt and his team. Whitt started off hot, batting .308 at the end of April, and the Blue Jays were in first place in the AL East at 26-19 at the end of May. Cox’s catching platoon of Whitt versus righties and Buck Martinez against lefties was also successful. Whitt batted .272 against righties, with 17 home runs, while the veteran Martinez hit .270 versus southpaws.24 Whitt’s fielding percentage (.992) ranked fifth among catchers and he remained in the top five in that category in five of the next six years. The Blue Jays had their best season in franchise history yet (89-73) and finished in fourth place.

Whitt realized he was part of a rising team as the 1984 season dawned. “You could see the younger players developing,” he said. “In ’84 when the Tigers got out to such a great start (35-5), we were still right with them. I think if we would have had a closer that year, we could have competed with them and made it a lot closer.” Toronto hung close to the surging Tigers through May, but by the end of June were 10 games behind despite a strong 45-31 record. The Tigers easily won the division by 15 games and rolled over all opponents on their way to a World Series title. But the Jays (89-73) were primed for a run of their own. Whitt had his usual consistent numbers at the plate (.238-15-46), and his .994 fielding percentage was third among AL catchers.

The 1985 season was a memorable one, as the Blue Jays won the AL East for the first time. Whitt helped guide Toronto’s top four starting pitchers: Dave Stieb, Doyle Alexander, Jimmy Key, and Jim Clancy. Three of them had double-digit victories, and all four had ERAs under 3.78. The staff as a whole led the league in ERA (3.31), the fewest runs allowed per game (3.65), and WHIP (1.24). Stieb led the league with a 2.48 ERA, and Tom Henke arrived from Triple A to secure their need for a closer. Henke was unscored upon in his first 11 appearances, finishing with 13 saves down the stretch for a team that ranked second (47) in saves. On the batting side, their batting average (.269) and hits (1,482) were second only to Boston’s. Despite the artificial turf at Exhibition Stadium, the Jays were first in defensive efficiency. Whitt’s WAR value of 2.5 ranked him sixth on the team.

The Jays took over first place for good on May 20 and built their lead to 9½ games in early August. Defensively, Whitt (.245-19-64) ranked fifth in putouts (649), and third in games (134) as he joined five other Blue Jays with double-digit home runs. One of those home runs came in a memorable game on June 23. Earlier in the month, Boston pitcher Bruce Kison and Jays second baseman Damaso Garcia had words with each other and had to be restrained. On this day, Kison was facing the Blue Jays at Exhibition Stadium. He knocked Ernie down with a pitch and brushed back Rance Mulliniks. Then he hit George Bell, who charged the mound and karate-kicked Kison, with both benches emptying. Whitt later knocked Kison out of the game with his bat: a grand slam in the sixth inning for an 8-1 Toronto win. Whitt, so steamed at Kison, didn’t even realize it was a grand slam until he made it around the bases. “I was just yelling at Kison, calling him every nasty name I could think of,” he remembered.25

Whitt was an All-Star in 1985, serving as a backup to Carlton Fisk, nine years after pinch-hitting for Pudge in his first at-bat. “For me, it’s an honor to be here. I really didn’t think it would happen. I’m having a good season offensively, and that helped me get here. But I think I can do better defensively.”26 He replaced Fisk in the sixth inning. He caught two innings and didn’t bat in his only All-Star Game appearance.

Despite a seven-game lead in the division on September 24, the Jays slumped down the stretch. They lost four in a row and saw their lead dwindle to two games over the Yankees, who arrived for the final three-game series of the season. The champagne was ready to pop during the Friday night opener, but in heartbreaking fashion the Yankees stunned all of Toronto with a ninth-inning comeback. Now the pressure mounted on the Jays to win just one more game for the AL East title.

On Saturday, October 5, before 44,608 anxious fans, Whitt made sure the Jays got on top first by blasting a second-inning home run off Joe Cowley. “We thought it was very important for us to score first,” Whitt said. The Blue Jays won, 5-1, and clinched the division. Whitt joined Jim Clancy and Garth Iorg as original Blue Jays who now celebrated a division title. “The first four years here seemed like a century,” he said. “We’ve been able to put tough losses behind us. I don’t think we’ve ever had a tougher one than Friday.”27

The Blue Jays suffered more heartbreak, however, failing to reach the World Series. “For us to win the Eastern Division and to play in the Championship Series was nice,” Whitt said. “It was disappointing, though, because we were up three games to one on Kansas City, but they came back to beat us.”28 Whitt batted a meager .190 in the ALCS against the eventual World Series champion Royals. Whitt later revealed he had played through a muscle tear in his shoulder after breaking up a double play in an early September game, which hampered his performance.29

Back trouble plagued Ernie during spring training in 1986, and he missed a couple of weeks in April. Injuries mounted for the Jays as well; they played sub-.500 ball through the end of May. Whitt and Martinez were batting a combined .175 at the end of May as the Jays found it a difficult road to repeat as division champions. But both player and team started to improve. Ernie’s 11th-inning walk-off home run gave Toronto an 8-7 win over Texas on August 17 in a game that was going to be suspended within the hour because of a Bill Cosby concert. Had the suspended game resumed the following day, it would have interfered with Whitt’s charity golf tournament. “I wanted to play golf tomorrow, not baseball,” said Whitt.30 The Jays had a strong August but couldn’t overcome the Red Sox, who beat them, 12-3, on September 28 and clinched the AL East. Whitt batted .336 in August and September to finish with his usual dependable numbers (.268-16-56).

Whitt’s contract expired after the season, during the era when the owners colluded not to sign free agents. Ernie felt he was worth $900,000 a year and a three-year contract, on par with other veteran catchers like Fisk, Rich Gedman, Lance Parrish, Ozzie Virgil, and Jody Davis. Settling for arbitration would give him only a one-year deal. Pat Gillick offered two years at $700,000 a year with an optional third year. The back-and-forth negotiations with the Jays resulted in an unsatisfactory deal in which Whitt felt he was not being paid what he was worth. “I feel like I’ve got a cauliflower ear from all the phone calls,” he said after negotiations ended in the wee hours of the morning of January 9, 1987. “I’m glad I’ve got one of those call-waiting things on my phone. It paid for itself this week,” he said. The contract was reported to be a two-year deal for $2.3 million with a third-year option. “I don’t think I got what was my worth, I feel, in today’s market,” he said. “Definitely the swing is on the owners’ sides and your hands are tied. I felt I gave up an awful lot.”31

Whitt had consistent numbers at the plate again in 1987 (.269-19-75) for what he considered the best team he ever played on. Blue Jays pitchers again led the league in ERA (3.74) and WHIP (1.30). Whitt ranked second in the AL in games as a catcher (131), first in putouts (803), second in throwing out basestealers (46) and second in fielding percentage (.994). The Jays spent much of the season in second place, within a handful of games of the division lead. Witt’s two-run ninth-inning double in Chicago on August 5 gave Toronto a dramatic 3-2 win to stay one-half game behind the Yankees. Whitt batted .344 in August to help the Jays’ cause.

His bat cooled in September, however, as the Blue Jays made their move toward their second division title in three years. Mired in a 3-for-29 slump on September 11, Whitt came through against one of the toughest lefties in the game. With the winning run on second in the bottom of the 10th of a 5-5 game, Whitt, who batted only .238 against lefties all year, lined a single to right off Dave Righetti to win the game and keep Toronto tied with Detroit for first place. On September 14 he had a career night and was part of baseball history in an 18-3 mauling of the Orioles. Whitt smashed three home runs off three Orioles pitchers and the Jays hit 10 home runs in the game, still a major-league record through 2017. “I don’t know. I’ve never been on a streak like this before,” Whitt said after the game. “I can’t deny I wasn’t thinking home run that last time. I’ll never forget this night, but this is no time for celebration. It’ll be something I can, one day, tell my grandkids but, let’s face it, tonight means nothing if we don’t win this thing.”32 The win kept the Blue Jays tied with Detroit at 86-57.

Whitt was involved in a controversial play on September 17 that cost the Blue Jays a win in the heat of the pennant race. With the Blue Jays leading the Yankees, 5-4, in the eighth inning at New York, Toronto’s David Wells fanned right-handed hitter Phil Lombardi on a pitch down and in. Home-plate umpire Larry Young was blocked from seeing the pitch, so first-base umpire Joe Brinkman raised his hands indicating a strikeout. Whitt, the out recorded, threw the ball to third so it would go “around the horn.” But while he was doing so, Yankees manager Lou Piniella thought Whitt had not fielded the ball cleanly and yelled at Lombardi to take off for first, where he stood. Piniella stormed out of the dugout to plead his case. Third-base umpire Tim Welke agreed with Piniella that Whitt had not caught the ball cleanly. The umpires decided Lombardi was safe. Toronto manager Jimy Williams went on a tirade and was ejected. Whitt was irate. “It’s the first time I’ve ever heard of a guy [Welke] who was in the worst position to see a play overruling the guy [Brinkman] who was in the best position. He [Lombardi] didn’t take off right away. He knew he was out so he went to the dugout. He didn’t run to first until Lou started shouting at him.” The Yankees wound up tying the score and winning that game. It was a costly loss which may have changed the entire season. Williams called Brinkman “gutless.” “If he saw the play and he called it a catch, why is he running around getting dissenting opinions?” wrote Al Strachan of the Globe and Mail. “Once he has decreed that Whitt caught the ball, how can he expect Whitt to make the play to first? The batter has been called out. The play is over. End of chapter. Get another hitter up.”33

Whitt didn’t mince any words in his autobiography concerning Brinkman. “Joe Brinkman hates our ballclub,” he wrote, creating national headlines when the book was published. “I used to talk to Joe all the time until 1987. Now we don’t speak at all. He’s one of the few I purposely won’t speak to because I think he’s gone downhill as an umpire. He’s incompetent. And the scary part is he runs an umpiring school.” In remembering the call, Whitt wrote, “(Brinkman) let a rookie umpire (Welke) from the opposite side overrule him, and that should never have happened.”34

After a thrilling, 10-9 walk-off win over Detroit on September 26, the Blue Jays led Detroit by 3½ games with just seven games to play. The season unraveled for the Blue Jays and Whitt from that point on. After a loss to Detroit, the Jays had a series against the Milwaukee Brewers. They would drop the opener, but still held a 2½-game lead with five games left. On September 29, Whitt collided with Paul Molitor at second base and broke two ribs. “I felt the knee go directly into my ribs,” he said. “I had trouble breathing. It was pain I’d never experienced before.”35 He watched the Blue Jays lose that and the following game to the Brewers, and the Tigers cut the lead to one game. Motown now anticipated the closing-weekend three-game series between the two clubs at Tiger Stadium while Whitt hoped to get back on the field.

Whitt dominated his hometown Tigers throughout his career, slamming 23 home runs, or 17 percent of his career total. Eleven of those homers came at Tiger Stadium. His 73 RBIs against them also proved headaches for Tiger pitchers. “I just really enjoyed hitting at Tiger Stadium,” Whitt said. “A lot of teams you play, [pitchers] make a mistake and you foul it off. It seemed with the Tigers, I was always able to hit their mistake pitches.”36 This series would not be a celebratory homecoming for Whitt, however.

“I remember going through all types of hell, basically trying to get in there to play,” Whitt recalled. “I had shots to numb the area, flak jackets, the whole nine yards. I never got in. There was no way Friday.” The Jays lost the opener, 4-3, and now the two clubs were tied for first with two games remaining. Whitt was available for pinch-hitting, but even that was a stretch. On Saturday he sat on the bench in stunned silence as Alan Trammell’s bases-loaded single in the 12th inning gave the Tigers a 3-2 win. The Blue Jays now needed to win the season finale to force a one-game playoff. Whitt sat out Sunday as the Jays faced tough lefty Frank Tanana, who threw a complete-game six-hit shutout in the 1-0 victory. The Jays had an epic collapse. “I was more than a little pissed off that I had gone through all the agony of trying to numb the pain, getting myself ready to pinch hit, showing (Williams) in batting practice that I could swing the bat and then not get used in a situation where I could have helped,” Whitt said.37

The 1988 Blue Jays started a sluggish 21-29 and were 12 games out of first to start the season. Whitt struggled too, as he allowed the most stolen bases in the AL (90) and was second in passed balls (10) but was also was fourth in throwing out basestealers (34) and second in putouts (643) and fielding percentage (.994). He batted .251 with 16 home runs and 70 RBIs and played 123 games behind the plate. The team came alive in September, going 20-7 and cutting a 9½-game deficit to two at the end of the season, but had still too many games to overcome. Yet they were resilient to the end. On September 27 Boston was a win away from clinching the AL East, but Whitt tied his career best with six RBIs to go with two home runs as Toronto blasted Boston, 15-9.

At the end of the season, the Jays exercised their $850,000 option on Whitt for 1989. He had been granted free agency by an arbitrator in the Collusion II case but preferred to stay in Toronto. Now 37, he hit 11 home runs, his fewest in seven years, and his RBIs (53) were his lowest in five years. But one of those home runs was a memorable one in Boston on June 4. The Red Sox led 10-0 in the seventh when the Jays mounted a dramatic comeback. They scored two runs in the seventh, four in the eighth, and five in the ninth, highlighted by Whitt’s grand slam against Lee Smith. Toronto prevailed, 13-11, in 12 innings.

The team flew back to Toronto and the next day played the inaugural game at SkyDome. Appropriately, Whitt, the last of the original Blue Jays, was the starting catcher. Two nights later he went 3-for-3 with three RBIs in the first baseball game played both indoors and outdoors, as SkyDome’s retractable roof was closed during the game.38

The Blue Jays played poorly early in the 1989 season, costing manager Jimy Williams his job. He was replaced by Cito Gaston on May 15, and the Jays caught fire in the second half, playing .627 ball. After falling 10 games behind Baltimore in the AL East race on July 5, the Blue Jays were one game ahead on September 1 and survived the division race by two games over Baltimore to reach the postseason for the second time. Whitt, who batted .300 in the first half of the season, hit only .220 in the second. He was platooned with Pat Borders. Whitt went 2-for-16 in the ALCS, his last appearance in the postseason, and the Jays lost the series to the Oakland A’s, four games to one. Whitt’s last at-bat in a Blue Jays uniform was a groundout in the ninth inning of Game Five, a 4-3 loss that ended Whitt’s season and lengthy playing tenure in Toronto.

The Blue Jays planned their future catching core around Borders and Greg Myers, but wanted to keep Whitt as a third-string catcher and DH. That was not the direction Whitt wanted to go in. “I wasn’t ready to accept being a third-string catcher,” he said. “I’ll always cherish my time in Toronto — I’ll miss the city, the fans, my teammates — but this, apparently, was something that had to be done. It was tough but, because I wanted to keep playing, I felt it was the only decision I had.” Whitt, as a 10-year veteran with five consecutive years at Toronto, could veto any trade. He agreed to be traded to Atlanta (where his former manager Bobby Cox was the GM) on December 17, when he was sent with outfielder Kevin Batiste for reliever Ricky Trlicek. “Negotiating with Bobby was the easy part. Basically, I got an offer I couldn’t refuse, but the tough part was accepting … actually saying, ‘Yes, we have a deal.’ I’m leaving with good feelings and I hope the Jays feel the same way about me,” Whitt said.39

The trade meant the Braves picked up the remaining year left on Whitt’s contract, which paid him $1.15 million and included an option year with a buyout clause. “We got a catcher that can hit,” said Cox. “He’s so much better than the other guys who are available. He’s an outstanding competitor. All Ernie wants is to play.”40

At 37, Ernie was surrounded by young stars who made the Braves the celebrated “team of the ’90s.” But they were still a year away, and the Braves of 1990 would have their sixth straight season of at least 89 losses. Manager Russ Nixon planned to platoon Whitt with veteran Jody Davis, who had hit a meager .169 as the Braves starter in 1989.

Whitt started the first game of an Opening Day doubleheader and went 0-for-1 before being pinch-hit for in an 8-0 loss to San Francisco. His only season in the National League was a lost one, as he batted a weak .171 at the end of May when he injured his thumb making a tag at the plate against Montreal. He did not return until the end of July. Rookie Greg Olson batted a hot .308 in June, was selected as an All-Star reserve, and all but secured the Braves starting catcher’s job.

By the time Whitt returned, Nixon was gone and Cox became the manager, where he would stay for the next 21 years of his Hall of Fame managerial career. But Whitt (.172-2-10 in 180 at-bats) had a disastrous season and the Braves bought out his contract for $475,000.41 “I just stunk the place out,” he admitted, conceding that his thumb injury contributed. “I don’t know whether the switch of leagues affected me, but I know the injury had a lot to do with it.”42

Whitt was given one final chance to extend his career. The Baltimore Orioles invited the veteran to spring training as a nonroster player for 1991. He was solely a backup to Bob Melvin and Chris Hoiles. He impressed the Orioles with his bat, batting .333 in his first 12 at-bats in spring training with two home runs. One was against Toronto at their spring park in Dunedin, Florida, where the crowd showed their appreciation for him with a standing ovation. “It’s nice when people respect you for what you have done,” Whitt said. “I was actually embarrassed a little bit.”43 Whitt made the club, receiving a $300,000 incentive-laden contract from Baltimore.44 He had a frustrating debut for the Orioles on April 14 when he struck out four times, three against Nolan Ryan. That is understandable against the future Hall of Famer, but for Whitt it ended his career against the Ryan Express: 0-for-10 with nine strikeouts.

The 1991 season was just as forgettable as 1990 had been. Whitt was batting .222 and starting only his 11th game of the season when he came up to bat in Toronto on June 14 for the first time since being traded. “Ern-nie, Ern-nie!” chanted the 50,000 fans who gave him a 40-second standing ovation at SkyDome as he came to bat. Whitt struck out and went 1-for-4 as his days were winding down. “It was really nice; the fans were great,” Whitt said. “I’m kind of excited, coming back home and all. I still consider this home. The fans here have been very supportive.”45 The end of the road came on July 5 when Baltimore released him. “I wasn’t surprised,” Whitt said. “If you look at it, I hadn’t started a game in 18 days. The writing was on the wall. Surprised, no. Disappointed, yes. I’d like to have finished the year with them, and I’m disappointed that I didn’t get to play more.”46

After 15 seasons, Whitt took off his catcher’s gear for the final time. “I wasn’t having fun,” he later said of his final season. “I told myself a long time ago that I’d get out of the game if it wasn’t fun anymore.” He stayed away from the game for the first couple of years to concentrate on having fun again: spending time with his family, golfing, and boating. But the game soon lured him back. In 1994, he and two groups of Canadian businessmen acquired the Blue Jays’ Class-A St. Catharines club. In 1996 he returned to his alma mater and coached the Macomb baseball team. “I’m doing something that I enjoy,” he told Bill Roose of the Detroit Free Press. “I guess I’m very fortunate because there are so many people out there that are doing what they don’t want to do out of necessity.” He also ran the Ernie Whitt Baseball Academy, which caused a public embarrassment to him in 1997 when the program suddenly closed due to mismanagement. Whitt had no ownership stake in the organization but approved instructors for the program. “It’s unfortunate what’s happened and I feel terrible about it,” Whitt said. “I feel like there’s egg on my face. I’ve worked too hard to have something like this blow up. The last thing I’d want to do is take advantage of any child, parent, or person. I’m going to do everything I can do from my end to get the money back to all the people.” He also shared a percentage of ownership of a golf and ski resort in Ontario. His tenure at Macomb lasted just the one season and in 1997 he was a roving catching instructor for the Blue Jays and also managed their Dunedin Class-A club for part of the season.47

Beginning in 1999, Whitt began managing Team Canada, which won its first-ever baseball medal (Bronze) at the Pan Am Games. The team placed fourth in the 2004 Olympic Games, won Bronze at the 2011 Baseball World Cup, and Gold at the 2011 and 2015 Pan Am Games. The team also participated in the 2006, 2009, and 2013 World Baseball Classics.

Whitt was a catching instructor in the Blue Jays organization until 2004. He then served as the Blue Jays bench coach from 2005 to 2007, then became their first-base coach in 2008. On June 20, 2008, manager John Gibbons and his entire coaching staff were fired, ending Whitt’s nearly two decades with the organization. He was hired by the Philadelphia Phillies in 2009 and spent a season as the manager of Clearwater of the Class-A Florida State League. After the season, Whitt became a roving catching instructor in the Phillies organization, where he continued into the 2018 season.

During his playing days in Toronto, Whitt gave back to his community, serving as chairman of the Canadian Cancer Society, and was actively involved in fundraising for the Special Olympics. Whitt was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 2009. The Whitts have three grown children: Ashley, EJ, and Taylor.

Last revised: December 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author was assisted by the following:

Cassidy Lent, Reference Librarian at the Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame, who provided copies of Whitt’s file and questionnaire.

“Ernest H. Whitt. Supervisor, Was Ballplayer’s Dad,” Detroit News, September 25, 2002.

“Ernie, Ernie!” Toronto Sun, June 19, 1989: A20.

Notes

1 Julie Kotsos, “Winter Fest Parade Draws Thousands to Downtown Windsor to See Santa,” Windsor Star, November 25, 2017. https://windsorstar.com/news/local-news/winter-fest-parade.

2 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 416.

3 Ernie Whitt and Greg Cable, Catch: A Major League Life (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1989), 10.

4 Ibid.

5 Whitt and Cable, 12.

6 Joe Sexton, “Blue Jays’ Catcher Rooted for the Tigers,” New York Times, September 28, 1987: C3.

7 Jim Evans, “The Whitt and Wisdom of Roseville High’s Athletic Hall of Fame,” Macomb Daily (Macomb County, Michigan), January 22, 2018. https://macombdaily.com/article/MD/20180122/SPORTS/180129897.

8 Mike Downey, “At Whitt’s End: A Position as Budding Big League Star,” Detroit Free Press, April 15, 1982: F1.

9 Bill L. Roose, “Ex-Major Leaguer Whitt Back in the Game as Macomb Coach,” Detroit Free Press, April 4, 1996: 6D.

10 Whitt and Cable, 41.

11 Whitt and Cable, 42.

12 “Six Players Sent Down; Tony Idle,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1975: 19; Peter Gammons, “Red Sox Cut 3; Guerrero Still Waits,” Boston Globe, April 3, 1975: 32; “Bristol Defeats Reading in 17th,” Hartford Courant, September 5, 1975: 58.

13 Whitt and Cable, 45.

14 Whitt and Cable, 47.

15 Evans.

16 Whitt and Cable, 50.

17 Bill Newell, “Whitt Living Baseball’s Highs and Lows,” Hartford Courant, March 31, 1977: 61.

18 Cathal Kelly, “Whitt, Ashby Share History: Ex-Jays Catchers Recall Excitement About April 7, 1977.” Toronto Star, April 10, 2007: C2.

19 Neil MacCarl, “Whitt and Jays Have Grown up Together; Veteran Catcher a ‘Father Figure’ Now,” Toronto Star, February 7, 1988: F11.

20 “Winfield Remembers Being Poor,” Detroit Free Press, August 18, 1977: 2D.

21 MacCarl.

22 Whitt and Cable, 69-71.

23 Downey.

24 Kevin Boland, “Witt’s Hit Testimony for Platoon System,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), June 22, 1983: S2.

25 Whitt and Cable, 2.

26 Larry Whiteside, “Catching the Fever; All-Stars Fisk, Whitt, Gedman of Same Mold,” Boston Globe, July 16, 1985: 33.

27 Bob Elliott, “Jays Finally Clinch It; Scoring First Run Was Crucial; Blue Jays 5, Yankees 1,” Ottawa Citizen, October 7, 1985: B1.

28 Roose: 6D.

29 “Whitt Wounded, Not Weary,” Globe & Mail, October 18, 1985: D14.

30 “Whitt Whacks Winner as Jays Jolt Rangers; Jays 8, Rangers 7,” Ottawa Citizen, August 18, 1986: B3.

31 Neil MacCarl, “A Look at Whitt’s Longest Day: Marathon Negotiations Result in $2.3 Million for Jay,” Toronto Star, January 10, 1987: D1.

32 Allan Ryan, “Home Run Kings Whitt, 3; Bell, 2; Mulliniks, 2, etc. etc. etc.” Toronto Star, September 15, 1987: E1.

33 Al Strachan, “Anatomy of a Controversial Call,” Globe and Mail, September 19, 1987: E5.

34 Whitt and Cable, 87-88.

35 Charlie Vincent, “Pain Sabotages Whitt’s Dream Night,” Detroit Free Press, October 3, 1987: 5D.

36 Roose: 1D.

37 Whitt and Cable, 243.

38 “Today in Baseball,” Baltimore Sun, June 7, 1991: 33.

39 Allan Ryan, “So Long, Ernie! Last of Original Jays Traded to Braves for a Minor-Leaguer,” Toronto Star, December 18, 1989: D1.

40 Joe Strauss, “Braves Acquire Whitt to Fill Need at Catcher,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 18, 1989: E1.

41 Joe Strauss, “Braves Will Buy Out Whitt for $475,000,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 12, 1990: D1.

42 Kent Baker, “Whitt OKs Invitation From Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, January 29, 1991: C1.

43 Kent Baker, “Whitt’s Hitting Gives Him Solid Chance to Catch On,” Baltimore Sun, March 19, 1991: 6D.

44 Kent Baker, “Orioles Complete Roster, Sending Milacki to Suns,” Baltimore Sun, April 8, 1991: B1.

45 “Whitt Still a Fan Favorite with Blue Jay Fans,” Edmonton Journal, June 16, 1991: D5; Neil A. Campbell, “Whitt Returns to Glory; Warm Reception Greets Former Jay,” Globe and Mail, June 15, 1991: A12.

46 Peter Schmuck, “Team Reaches Whitt’s End; Chito Martinez Brought Up,” Baltimore Sun, July 6, 1991: 23.

47 Roose: 1D; “Former Jay Catcher Whitt to Buy St. Catharines Team,” Toronto Star, November 10, 1994: B8; Randy Starkman, “Kids Feel ‘Ripped Off’ as Baseball School Closes; Ex-Blue Jay Embarrassed as Owners Tell 200 Cheques in Mail,” Toronto Star, February 15, 1997: A3; Jim Byers, “Moseby Back with Jays,” Toronto Star, October 18, 1996: C5; John Lowe, “Slumping Boggs, O’Neil Benched,” Detroit Free Press, October 12, 1996: 3B.

Full Name

Leo Ernest Whitt

Born

June 13, 1952 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.