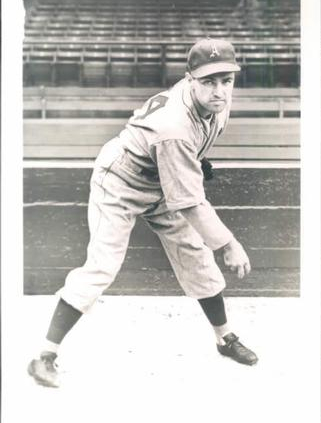

Nels Potter

Entering the twilight of a 12-year major league career, Nelson Potter joined the Boston Braves in midseason of 1948 and became the top relief man and spot starter for the NL champs with an impressive 5-2 record and a 2.33 ERA. This was his second stint with a pennant-winning team; as a nearly full-time starter, he had been the ace of the 1944 St. Louis Browns staff with a 19-7 record. He was on his way to a 20-win season in that campaign when he became the first player in big-league history to be ejected (and suspended) for throwing a spitball, but always denied “loading up” then or at any time in his career. His screwball and slider were tough enough on batters, and while he is not remembered with the reverence of a Warren Spahn or Johnny Sain, his success with these two legal pitches played a big role in Boston’s National League club reaching its first World Series in 34 years in ’48.

Entering the twilight of a 12-year major league career, Nelson Potter joined the Boston Braves in midseason of 1948 and became the top relief man and spot starter for the NL champs with an impressive 5-2 record and a 2.33 ERA. This was his second stint with a pennant-winning team; as a nearly full-time starter, he had been the ace of the 1944 St. Louis Browns staff with a 19-7 record. He was on his way to a 20-win season in that campaign when he became the first player in big-league history to be ejected (and suspended) for throwing a spitball, but always denied “loading up” then or at any time in his career. His screwball and slider were tough enough on batters, and while he is not remembered with the reverence of a Warren Spahn or Johnny Sain, his success with these two legal pitches played a big role in Boston’s National League club reaching its first World Series in 34 years in ’48.

Born August 23, 1911, in Mount Morris, Illinois to farmer Irving Potter and his wife, Ida Mae, Nelson was an all-sport high school star — leading both the baseball and basketball teams into state tournaments. In addition to his pitching prowess he captained the football squad and, despite being just 5-feet-11, jumped center for the hoopsters. He even won trophies in track for the shot put and discus. Mount Morris teammate Everett Henderson remembers Potter as a “superb athlete” who was equally proficient in tennis and horseshoes and later in life shooting pool and bowling (after retiring, Potter built and managed a bowling alley).

As an example of Potter’s ability to dominate in any sport, Henderson recalls a tournament basketball game when Mount Morris was trailing by five points with less than a minute to go: “In those days there was a center-jump after every basket. Nelson said, ‘Buck, I am going to tip the ball to you, shoot it to Dopey and then he is going to pass it back to me for the shot.’ (Everyone in our small town of 3,000 had a nickname.) We did the same play three times in a row and won the game by a single point.”1

Potter’s son Nelson Jr. similarly recalls his father as a “gifted natural athlete at any sport he tried. He never played a round of golf but he could drive golf balls out of sight. He had not bowled before building the bowling alley but soon carried an average around 200. He was also an expert pool and billiards player who made a modest amount of money playing those sports at a time when money was no doubt hard to come by.”2

Given his skills, it was not a big surprise when Potter left Mount Morris College in his junior year to sign with the Chicago White Sox after helping the school tie for a 1932 title in the Little Nineteen League (made up of small Midwestern colleges). His son James recounts the story passed down to him: “The local doctor in Mount Morris knew a trainer with the White Sox and through that contact he was given a tryout and inked to a minor league contract.”3

His first pro experience was likely also Potter’s first time struggling on the diamond. Assigned to Waterloo, Iowa, in the Class “D” Mississippi Valley League, he ended the season with a 5-10 record and a 4.86 ERA. He had no better success the next year, 1933, with Lincoln in the Nebraska State League (4-6, 6.72) but in his second summer with Lincoln he turned around. Potter pitched his only no-hit, no-run game as a pro against Norfolk, and his earned-run average of 1.71 led the circuit. He posted a 17-9 record, struck out 200 in 216 innings, and received honorable mention in league All Star balloting. In a letter recapping his minor-league career Potter described his no-hitter, which was nearly a perfect game: “… (I) struck out 14 men and only pitched to 27 batters. One man walked but the next man hit into a double play.”

When the Mississippi Valley League folded, Potter wrote, the White Sox released him rather than pay his back salary. He signed with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1934 and spent three years with farm teams in their organization — one year at Houston (1935), followed by two with the powerful Columbus Redbirds of the American Association (1936-1937). St. Louis did bring him to the big leagues in ’36, but he pitched just one scoreless inning before being returned to Columbus for more seasoning. While there, he shared the mound with future major leaguers Mort Cooper and Max Lanier. Potter was regarded as a “right-hand relief hurler de luxe,”4 appearing in that role in 33 of 44 games pitched in 1937. He went 11-11 with a solid 3.56 ERA, and really shined in the postseason. As Potter later recalled, after once winning three games in three days during the regular season, he pitched in five of seven games against Newark in the Little World Series in 1937. He was a relief pitcher in the first four games and started the seventh and final contest, but was the losing pitcher.

After his playoff heroics, the Philadelphia Athletics took Potter in the Rule V draft and brought him up to the majors the next year. He started 62 games over the next 3½ years before being traded to the Boston Red Sox in midseason of 1941, and while his record with the woeful A’s was an unimpressive 20-37, he did have several bright spots. In the spring of ’38, for example, he relieved at Detroit with the bases loaded and preserved a one-run lead by retiring the heart of the Tigers’ order — Charlie Gehringer, Rudy York, and Hank Greenberg. On August 10 of that year he pitched perfect ball for six innings against the Red Sox, and in a 1940 game he stopped an A’s losing streak with a seven-hitter in early May. The same month he hurled the last six innings against the White Sox, yielding only two hits and facing 19 batters to preserve a 3-2 victory.

The A’s never rose above seventh place and averaged 99 losses a year from 1938-40. There was little room for pitcher error, and Potter’s overall 1940 performance — he went 9-14 with 13 complete games for a 54-100 team — prompted Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich to note, “The pitcher that’s getting a tough break this year is Nelson Potter of the A’s. He’s pitching great ball and the A’s are kicking ‘em away for him. He’d win 20 games with a good ball club.”5 Arch Ward of the Chicago Tribune wrote, “American League players vote the title of the year’s tough luck pitcher to Nelson Potter.”6

His fortunes were far better off the diamond during this period. On October 10, 1937, “Nels” (one of his several nicknames that also included “Clint” and “Popcorn”) married his high school sweetheart, Hazel Park. Nelson Jr, who was born two years later, explains the Clint nickname: “My father was called Clint because, the story goes, during high school he was put upon by a local bully named Clint, and one day he took care of the problem by giving him a thorough enough beating that the bully never bothered him again. After that my father was called Clint.”7

Such toughness clearly served Potter well, since throughout his baseball career he was plagued by a high school basketball knee injury. As he recalled, “It was a game in Rochelle, Illinois. I had the ball and started to make a quick pivot when one of the heavier opponents ran over my right foot, pinning it to the floor. My knee pivoted, but my foot didn’t. It sure ripped hell out of the cartilage.” The injury became worse in 1938, and after a dismal 2-12 season with Philadelphia, he decided on surgery. The procedure was not successful (the doctor removed the wrong ligament) and two years later Nels went under the knife for a second time.8 It required a full year of therapy for the knee to regain its full strength, and Potter developed his own method to strengthen it.

As younger son Jim remembers hearing, “To get his knee back into shape he hunted fox every day that winter (of 1938-39). My mother would drive around with my dad looking to spot fresh fox tracks. He would count how many fox tracks went in and how many went out of the area. More going in than going out meant there was a fox in there, so he chose the freshest-looking track and then my mother would let him out of the car and go home. My dad would track foxes all day long from first light until night and then call my mother from some farmhouse miles from where she left him off. He would have several fox pelts, and then they would do the same thing the next day, all winter long. He and his knee got in excellent shape that winter.”9

Things weren’t perfect, however. Potter told Stan Baumgartner, a sportswriter for the Philadelphia Inquirer, that he had to pass up his usual offseason job in a print shop because of the knee trouble. The after-effects of the operation resulted in Potter’s being classified 4-F in the draft during World War II. As he assured journalist George Castle: “People asked then, how could you play ball and not serve in the military? I would have served, driven a truck, whatever, but they would not take me.”10

While recovering from surgery during the 1941 season, Potter was sold to the Boston Red Sox on June 30. Appearing in just 10 games for manager Joe Cronin’s club, he compiled a 2-0 record and an encouraging 4.50 ERA (he had been 1-1, 9.26 that year with the A’s). Unfortunately, the contending Red Sox didn’t see Potter for what he was — a determined pitcher about to blossom into a very successful one. In the spring of 1942, Boston sold Potter’s contract outright to Louisville of the American Association. That proved to be his turnaround year. He won 18 games for the Class “A” Colonels and four of his eight defeats were by either 1-0 or 2-1 scores. He pitched 212 innings, had an ERA of 2.12, and was second in the league with 148 strikeouts while giving up just 59 walks. He even boasted a .303 batting average with several pinch hits during the campaign.

Attributing his mound turnaround to developing a slider to go with his already effective screwball, Potter said he made the move to compensate for his sore arm and knee problems. At the end of the season, the hapless St. Louis Browns selected him in the major league draft for $7,500, an investment that would help result in the long-suffering franchise’s first and only pennant. Tommy Fitzgerald of the Louisville Courier-Journal noted: “If he had been blessed with a team less puerile at the plate, Nels probably would have bettered that glossy record of 18 and eight.… Potter’s specialty pitches are a screwball and a curve. He’s not fast, but uses his speed ball so judiciously in the midst of a lot of junk that he succeeds in slipping it by opposing batters quite often.”11

The 1943 season was Potter’s first winning campaign in the big leagues. He pitched in 33 games, both as a starter and reliever, and ended the year with a record of 10-5. He pitched eight complete games and had an ERA of 2.78, good for 10th in the American League. The Browns, however, were not much better than the A’s had been a few years before, going 72-80 and finishing sixth in the American League.

The ’44 season started on a low note for Potter when he was floored by a bad case of the flu during most of spring training, and failed to pitch even an inning before Opening Day. But he hurled a six-hitter in the third game of the season to beat the White Sox, 5-3, then followed this up with another complete game against Cleveland in a 5-1 victory. Nels had thus contributed two of the eight consecutive wins the Browns registered to kick off the season. In addition to putting the Browns into the uncharacteristic regions of first place, the opening streak also topped the previous record of seven straight wins at the beginning of a season (set by the Yankees in 1933).

Potter also registered the first shutout of the season for the Browns, a 2-0 performance against Detroit in early May. A few weeks later he retired the first 23 Red Sox he faced in a game at Sportsman’s Park, and by July 20 he was 9-5 when he took the mound against the Yankees in a game that would end up in the record books. Early in the contest, Browns manager Luke Sewell approached umpire Cal Hubbard to protest that New York pitcher Hank Borowy was moistening his fingers before delivering pitches. That, of course, brought the ump’s attention to Browns hurler Potter; Hubbard warned Potter that he was doing the same thing his manager was complaining about, but to no avail.

In an interview the next day, the umpire said, “I warned Potter in previous games and I feel that I have given him every possible break possible. Sewell himself forced the issue last night by kicking about Borowy’s pitching methods. The warnings were not prompted by any protest from the Yankee side until after Sewell asked me to warn Borowy.”12 Potter wound up being ejected by Hubbard in the fifth inning and ultimately was suspended for 10 days. The Browns did go on to win the game, however, which helped quiet a crowd of 13,093 — some of whom had pelted the field with an assortment of bottles and straw hats after Potter’s exit. In a 1982 interview with the Rocky Mountain News, Hubbard recalled the incident in the following manner, “He (Potter) has a wife, and I think he wanted a vacation anyway. They said his wife gave birth to a child nine months later. I gave him the chance to be home.” “That’s true,” said Potter when reminded of the story. “And one thing you can be sure of, I didn’t name him Cal Hubbard Potter.” (A son, James, was born to Hazel and Nelson on April 19, 1945.)13

Many years later, speaking before an audience at a convention of the Society for American Baseball Research, Potter said, “The truth is I have never thrown a spitball in my life. It was a cool, dry night and we were playing the Yankees. I was using the rosin bag, Cal Hubbard said I couldn’t go to my mouth with my hands that night. I then blew on my hand. Cal said, ‘You can’t do that.’ I threw the ball in and said there was no rule that says you can’t do that. He kicked me out of the game and I got suspended for 10 days.”14

Potter returned to the Browns’ lineup on August 6, winning the second game of a doubleheader against the Indians, 6-4, and helping his own cause with two hits in three trips to the plate. But more trouble — and more headlines — were in the near future. Later that month he fielded a bunt in foul territory and, without warning, he and the Washington Senators’ batter, George Case, started swinging fists. Both benches cleared, prompting the police and military police to join the fray and quiet the players; when it was over Case and Potter were tossed and fined $100 by league president Will Harridge. (This time, luckily, there was no suspension.)

Despite all the turmoil, Potter pitched the best baseball of his career after the 10-day spitball “vacation.” He went 10-2 in August and September, and the Browns needed all of it during a heated pennant race. St. Louis was tied with the Tigers on September 26, when Potter blanked the Red Sox, 3-0, on two hits. Three days later the Browns ended the defending world champion Yankees’ hopes for a repeat with a doubleheader win, Potter shutting out the Bronx Bombers 1-0 in the nightcap. Amazingly, just 6,172 fans attended the Friday twinbill for the Browns, who had been laughingstocks for so long that some folks were no doubt still expecting they’d blow the race. They didn’t; two days later, with a team record 37,815 looking on at Sportsman’s Park (the Browns’ first sellout in 20 years), they clinched the pennant with a 5-2 victory.

The ’44 World Series was the first all-St. Louis match-up in the fall classic, and the seventh time that clubs from the same city competed for baseball’s highest team honor. It was also the first World Series for the Browns period in their 43-year history. Both the Browns and Cardinals played in Sportsman’s Park, and Potter worked out a deal with a Cardinals player to share a hotel room during the regular season since they were never in the city at the same time. During the Series, however, one of them had to move, for fear that if the media learned of the situation it might not look good.15 (Managers Sewell and Billy Southworth had the same roommate arrangement, but theirs did make the papers.)

Potter was the starter for the second Series game, and was lifted in the sixth inning for a pinch-hitter with his team trailing, 2-0. He was the victim of two unearned runs, throwing four-hit ball as the Browns made four errors in the game. Potter did not help his own cause as he committed a double error on what should have been a double play on a bunt by Max Lanier. Nels was taken off the hook later when the Browns scored two runs, but they lost in the 11th inning. The Cards won the next two games as well, so it was win or go home when the Browns took the field for the sixth contest. Manager Sewell started Potter, and after three innings he held a 1-0 lead. A three-run Cardinals explosion in the fourth, however, ended both Potter’s and the Browns’ hopes, and the Redbirds claimed their second championship in three years. It was hard to put blame on Nels, who again was the victim of shoddy defense; two of the three runs against him this time were unearned, and when combined with the two let in through miscues in the first game, left him with a sparkling Series ERA of 0.93 over 9⅔ innings.

As a small consolation, the Browns were voted the number one sports comeback in the United States by the Associated Press and Potter received several votes for American League most valuable player. During the offseason he returned to Mount Morris and worked as a high school basketball referee, claiming it was “great for the legs.” And, of course, he spent much of his time on his usual hunting and trapping. (This hobby had once proven extremely lucrative. In his youth he was known to trap as many as 14 muskrats in a single morning, for which he earned the sum of $2.50 per pelt. In his biggest year in baseball, by contrast, he earned $19,000.)16

The Browns dropped to third in 1945, but Potter continued his winning ways with a 15-11 record, three shutouts, and a terrific 2.47 ERA (sixth in the league). He helped his own cause during his first game of the season when he delivered a game-winning single in the ninth inning against the Indians, and a month later he scattered eight hits in winning his first shutout of the season, 5-0, over the Red Sox. But in the late spring and early summer, he lost seven consecutive games, before finally winning a 5-1 rain-shortened contest against the Washington Senators. And later in the season he racked up eight wins in a row, topped off with a masterful two-hit shutout against the first-place Tigers on September 24. One of his teammates in that season, the worst of World War II in terms of player shortages, was the one-armed Pete Gray. Although other Browns players ridiculed the .218-hitting Gray and grumbled that his presence on the team was a publicity stunt that cost them a second pennant, Potter had great respect for his teammate and made it a point to visit Pete after they both retired from the game.17

As a final reminder that the ’45 Browns had lost their magic of the previous year, Potter gave up a ninth-inning grand slam to Hank Greenberg of the Tigers on the last day of the season to help Detroit capture the American League pennant. St. Louis landed in third place with an 81-70 record, but they likely would have been much worse off without Potter; in addition to his stinginess on the mound, he was also one of St. Louis’ best hitters with a .304 average (28-for-92).

On April 16, the second day of the 1946 season, Potter faced the Tigers again, pitching against Detroit ace Hal Newhouser in Briggs Stadium. Potter lost, 2-1, as nemesis Hank Greenberg walloped a line drive into the left-field seats for the game-winner. This was a sign of things to come; both Potter’s and the Browns’ fortunes further declined during the year, with Potter posting an 8-9 record (with a 3.72 ERA) and the team dropping to seventh place. The season was also plagued with the defection of several St. Louis players to the Mexican League, including slugger Vern Stephens. Toward the end of the season Luke Sewell was replaced as manager by Zack Taylor.

Things got still worse in 1947; the Browns ended up in the cellar with a 55-95 record, while attendance dwindled to 320,474, lowest in the league. Potter had a bleak 4-10 record and was used much more as a reliever — starting just 10 games among his 32 appearances. It was also in 1947, however, that Potter, in his role as the Browns’ player representative, helped establish baseball’s first pension plan. “We made cash contributions to get it started [at the time of the interview in 1986 he noted that he was receiving less than an $800 monthly benefit].”18

In May 1948, Browns management declared its intentions to rebuild with a younger team. Potter, then almost 38 years old, was sold back to the Philadelphia Athletics, where he had pitched from 1938 to 1941. The A’s badly needed relief help, and Potter started by downing the Yankees twice in three days over the Memorial Day weekend. He relieved starter Lou Brissie in one of the contests with the bases loaded and no outs in the fifth inning, and pitched his way out of the jam without being scored upon. In his first five games with Philadelphia, Potter pitched 14⅓ innings and allowed just three runs while striking out 12. Longtime doormats since their last dynastic run in the early 1930s, the A’s were surprising contenders in the American League race thanks in part to the familiar face in their bullpen.

Aging A’s owner-manager Connie Mack soon became disenchanted with Potter, however, and fired him before a hushed clubhouse on June 13 after he blew a three-run lead in the space of only five batters. Mack exploded, “Go get your check. You are off the club.”19 Many of the A’s players thought the move cost the team whatever chance it had of winning the 1948 AL pennant. As Potter recalled, “Mr. Mack got excited about losing a ball game and flew off the handle. It isn’t true, as Mr. Mack inferred, that I wasn’t trying my best. I told him I was doing the best I could, but otherwise I kept quiet out of respect for his age. I won two games for him in New York and I saved one in Detroit. He thought I was doing all right then.”20

Potter quickly left for the Philadelphia airport and a flight home. When asked whether he felt down and out when let go by the A’s, Potter responded, “Down and out — no. I knew right then the A’s were doing me the biggest favor of my life. Some of the players wanted me to stay around until they could talk to Mr. Mack. But I would not have come back if he had asked me.”21 The firing did in fact turn out to be a blessing in disguise for Potter, as several strong teams lobbied for the versatile right-hander. The AL-contending Indians offered him $15,000, a large sum at the time, but he decided to sign with the National League-leading Boston Braves. It was the right move for both the pitcher and the club.

National League batters had not faced his screwball and slider, which helped Potter build an impressive 5-2 record with an ERA of 2.33 over the final three months as the team clinched its first NL pennant since 1914. He proved to be an effective backup for top starters Johnny Sain, Warren Spahn, and Vern Bickford, starting eight games while relieving in nine others. Pitching his first game as a starter on July 18 against the Pirates, he came away with a 10-2, seven-hit victory in which he helped his own cause with three hits and two RBIs. Nine days later he pitched a 5-1 six-hitter against the same club, and on September 12 he came out of the bullpen to win one of the most exciting games of the year by shutting out the Phillies in the 10th through 13th innings of a 2-1 victory. By year’s end he had compiled a fine 8-5 record with three saves and a 2.86 ERA over 28 games and 113⅓ innings with three teams.

Nels later claimed to have taught the screwball to future Hall of Famer Spahn during the ’48 season, which no doubt helped Spahnie stay a 20-game winner into his forties. In the World Series, however, Potter’s magic wore out. The aging hurler was hit hard by the Indians in two appearances totaling 5⅓ innings, including a Game Five start, as Cleveland took the Series in six contests. He was pleased and honored, however, that the Braves team voted him a full share even though he had been with the team for only part of the season.22

The next year, 1949, was Nelson Potter’s last in the major leagues; he pitched 96 innings, mostly in relief, and compiled a 6-11 record with seven saves. This dipped his career won-lost record under .500 for his 12 years as a big leaguer, to 92-97 with an ERA of 3.99. He had pitched a total of 1,686 innings and given up a meager 123 home runs, 62 of them coming during his first four-year tour with the A’s and prior to his knee operations.

At the end of the ’49 season, after finishing fourth, the Braves cast away many of their former heroes including Nels. Potter was picked up on waivers for $10,000 by the Cincinnati Reds, but declined the offer. He told Cincinnati president Warren Giles that he was returning to his native Mount Morris and his job as a pressman, and later explained, “I didn’t want to stay in baseball. I traveled for so many years, in a hotel on a road trip, you’d hang up your clothes for three days. So I was happy to hang my clothes in a closet at home.”23

One downside of Potter’s decision to retire is that it prevented a reunion with his Brownie skipper, Luke Sewell, now managing the Reds. In three seasons under Sewell at St. Louis, Potter had pitched 45 complete games in 74 starts, winning 44 times while losing only 23 with an ERA well under 3.00. Instead, back home, Potter coached a Junior American Legion team and played some semipro ball with the De Kalb Blue Sox retiring from the game altogether.

Now free to do what he wanted, where he wanted, Potter stayed close to home and became active in business and politics around Mount Morris. He continued to work as a skilled proof-press operator for several years until he built a bowling alley, Town and Country Lanes, in 1956, after inheriting land adjacent to the site. For a while the family lived in an apartment on the second floor above the establishment, and he later built a handful of homes including one for his family beside the lanes.24 The road is now named Potter Lane.25

For many years this dedicated family man served his community as township supervisor, maintaining 40 miles of rural roads. And for the last few years before his retirement he sold insurance, a job for which Nelson Jr. said he was well-equipped, “as he knew everyone and everyone knew him.” Four or five times a year the elder Potter would make the 2½-hour drive to Chicago and see the Cubs, and in 1988 he was named to the St. Louis Browns Fan Club’s Hall of Fame. He actually waxed nostalgic with teammates from both his pennant-winning clubs that year, as in August he went to Boston to participate in a celebration marking the 40th anniversary of the ’48 Braves’ NL championship, sponsored by the New England Sports Museum.

This would be the last time he saw most of his old friends from baseball. Nelson Potter died at his home of a heart attack while watching the Cubs play the Mets on television. The date was September 30, 1990 (the Cubs scored two runs in each of the last two innings and beat the Mets at Shea, 6-5). Potter was 79 years old. His wife, Hazel, had passed away in 1986, and they were survived by three children. Nelson Jr. teaches philosophy at the University of Nebraska, Barbara (now deceased) was a music teacher, and James is an executive with Tootsie Roll. In addition, he had three grandchildren. The memorial service and burial were in his beloved hometown of Mount Morris, and a more permanent tribute came in 2006 when Potter was inducted into the Manchester College Hall of Fame. Son James, representing the family, was in attendance. The inscription on the plaque reads:

Nelson “Clint” Potter Sr. ’34 is the first Hall of Fame inductee who attended Mount Morris College before it merged with Manchester College in 1932. Potter was a three-sport athlete-basketball, baseball and tennis, and was key to the Mount Morris offense and the leading scorer during the two years he attended the College.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Notes

1. Interview with Everett “Buckshot” Henderson, March 15, 2007

2. Interview with Dr. Nelson Potter Jr., April 4, 2007

3. Interview with James Potter, April 5, 2007

4. 1938 Spalding Guide, p. 143

5. Povich, Shirley. Washington Post, August 6, 1940

6. Ward, Arch. Chicago Daily-Tribune, August 14, 1940

7. Interview with Dr. Nelson Potter Jr., April 4, 2007

8. Ibid.

9. Interview with James Potter, April 5, 2007

10. Castle, George. Lerner Newspapers, August 12, 1986

11. The Sporting News, November 12, 1942, p. 9

12. St. Louis Post-Dispatch , July 21, 1944

13. Berler, Ron. Rocky Mountain News, February 22, 1982

14. Castle, George. Lerner Newspapers, August 12, 1986.

15. Interview with James Potter, April 5, 2007

16. Interview with Dr. Nelson Potter Jr., April 4, 2007

17. Ibid.

18. Castle, George. Lerner Newspapers, August 12, 1986

19. Povich, Shirley. Washington Post, July 9, 1949

20. Associated Press, Philadelphia Inquirer, June 14, 1948

21. Birtwell, Roger. The Sporting News, August 4, 1948

22. Interview with Dr. Nelson Potter Jr., April 4, 2007

23. Castle, George. Lerner Newspapers, August 12, 1968. Unlike many contemporary ballplayers Potter welcomed overnight travel. After a particular rough train ride the night before he was scheduled to start, Potter was queried by a sympathetic reporter as to whether he had been able to get much sleep. Potter responded, “Yes I slept fine. It’s a funny thing, but I can sleep better on a train than almost any other place I know.” To which Braves trainer Dr. Charles Lack interjected, “Nelson’s certainly in the right profession” The Sporting News, August 4, 1948.

24. Interview with Dr. Nelson Potter Jr., April 4, 2007

25. Interview with Everett Henderson, March 15, 2007

A number of the quotations ascribed to Potter come from a letter he wrote in longhand, in which he recapped his entire minor league career.

Full Name

Nelson Thomas Potter

Born

August 23, 1911 at Mount Morris, IL (USA)

Died

September 30, 1990 at Mount Morris, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.