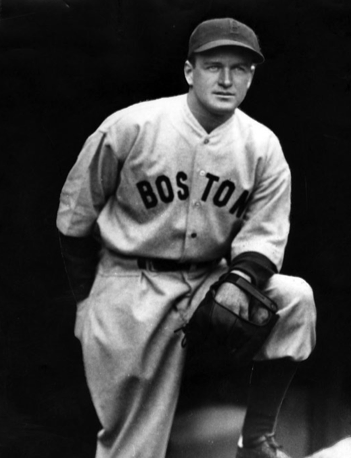

Joe Cronin

Star player, manager, general manager, league president—only one man in baseball history has followed a career path like this one. Joe Cronin, one of the greatest shortstops in the game’s history, spent 50 years in the baseball without being fired or taking a year off. Every job was a promotion, and he came within a whisker of being baseball’s commissioner in 1965. Late in life, reflecting on all his contributions and responsibilities over the years, Joe made it clear where his heart lay. “In the end,” said Joe, “the game’s on the field.”1

Star player, manager, general manager, league president—only one man in baseball history has followed a career path like this one. Joe Cronin, one of the greatest shortstops in the game’s history, spent 50 years in the baseball without being fired or taking a year off. Every job was a promotion, and he came within a whisker of being baseball’s commissioner in 1965. Late in life, reflecting on all his contributions and responsibilities over the years, Joe made it clear where his heart lay. “In the end,” said Joe, “the game’s on the field.”1

Joseph Edward Cronin was born in San Francisco on October 12, 1906, six months after the great earthquake and fire that devastated his home city. His father, Jeremiah, born in Ireland in 1871, had immigrated to San Francisco in either 1886 or 1887 in search of an easier life, but had found mostly hard work in the years since. His wife, Mary Carolin, was a native of the city, and the couple had two other boys—Raymond (b. December 1894) and James (b. July 1896). Jeremiah had a team of horses, which came in handy when it came to rebuilding the city. The family lost its home in the fire and was living with Jeremiah’s sister when Joe was born. In early 1907 they moved into a new house in the Excelsior District in the southern part of the city.2

The Cronins were Irish Catholics, and preached the virtues of family, hard work, and church. Joe’s brothers being much older, he was blessed with a lot of time to play sports, which neither of his brothers had done. San Francisco had a well-established system of playgrounds, with directors responsible for organizing teams in different sports, and playing games against other playgrounds. The Excelsior Playground, as luck would have it, was one block from the Cronin house.

Joe, a strong youth who grew to nearly 6 feet tall as a teenager, played soccer, ran track, and won the boys’ city tennis championship in 1920. But baseball was his first love, as it was for most athletes in the city. Though there were no major-league teams west of St. Louis, the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League became like the major leagues for the local fans. In addition, many San Franciscans had played for the Seals and then made good in the majors, including George Kelly, Harry Heilmann, and Ping Bodie, one of Joe’s early heroes.

In 1922 Joe teamed up with Wally Berger to help win the city baseball championship at Mission High. The following summer the school burned down, and while it was being rebuilt, Joe transferred to Sacred Heart, a Catholic school a few miles north of his home. Joe starred in several sports at his new school, and his baseball team won the citywide prep school title in 1924, his senior year. By this time, Joe was also playing shortstop with summer clubs and for a semipro team in the city of Napa, north of San Francisco.

Although Cronin had long dreamed of playing for the Seals, he passed up an offer to join the San Francisco club by taking a higher offer from scout Joe Devine of the Pittsburgh Pirates in late 1924. In the spring, Joe trained with the Pirates in Paso Robles, California, but soon joined the Johnstown club of the Middle Atlantic League, hitting .313 with just three home runs but 11 triples and 18 doubles in 99 games. At the end of the season, Joe and his friend and roommate Eddie Montague joined the Pirates, working out with major leaguers and sitting on the bench while Pittsburgh beat Washington in the 1925 World Series.

The Pirates were a strong club, especially at the positions Joe would most likely play. Shortstop Glenn Wright and third baseman Pie Traynor were among the best at their positions in the game, and the 19-year-old Cronin had very little hope of playing much in 1926. He traveled with the team early in the season, pinch-running four times and scoring two runs, before being assigned to New Haven in the Eastern League. This club was operated by George Weiss, near the start of a long career in the game that would eventually land him in the Hall of Fame. By midsummer, Cronin was hitting .320 and earned another recall to the Pirates. In the latter stages of the season Joe played 38 games, mostly at second base, a position he had never played. He hit .265 for manager Bill McKechnie, a promising start for the youngster.

After the season McKechnie was fired, and the new manager, Donie Bush, moved George Grantham from first to second base, blocking Cronin’s best path. Joe stuck with the 1927 club the entire season, but played just 12 games, hitting 5-for-22 (.227). The Pirates won the NL pennant again, but Joe had a miserable time and hoped to play in the minors rather than sit on the bench again. After spending spring training of 1928 with the team, he was sold by the Pirates to Kansas City (American Association) in early April. He was back in the minor leagues.

With Kansas City, Joe played mostly third base and struggled to regain his batting stroke after a year of playing so infrequently. In July he was hitting just .245 and feared he might be sent to a lower classification club. Instead, Joe’s ship suddenly came in. Joe Engel, a scout for the Washington Senators, was making a scouting trip in the Midwest when he discovered that Cronin, whom he remembered from the Pirates, was available. The Senators, it turned out, needed an infielder, and Engel made the purchase.

Joe reported to Washington in mid-July. When Engel brought him to meet Clark Griffith, the Senators’ owner, they first had to meet Mildred Robertson, Griffith’s niece and secretary. In fact, Engel had sent a telegram to Mildred before his arrival, warning her that he had signed her future husband.3 As it turned out, Joe and Mildred soon began a long courtship before being married after the 1934 season.

The Senators needed a shortstop, oddly, because of an arm injury suffered by left fielder Goose Goslin which kept him from throwing the ball more than a few feet. The club needed Goslin’s great bat so the shortstop, Bobby Reeves, had to run out to left field to retrieve his relay throws. Though hitting well over .300 in June, Reeves began to lose weight rapidly in the summer heat, and the team at least needed a capable reserve. Cronin began as Reeves’ backup, but eventually manager Bucky Harris began playing the newcomer most of the time. Cronin hit just .242 in 63 games but played an excellent shortstop and became a favorite of his manager.

After the season Harris was fired and replaced by Walter Johnson. Johnson was a longtime Senators hero, but was not familiar with Cronin at all and said only that he would keep an open mind. The next spring Johnson moved Ossie Bluege from third base to shortstop and installed Jackie Hayes at third, but an early-season injury to Bluege gave Cronin an opening, and his strong play forced the recovered Bluege back to third base. In 145 games, including 143 at shortstop, Joe hit a solid .282 with eight home runs and 29 doubles. His 62 errors, due mainly to overaggressive throwing, did not cause alarm. Turning 22 that fall, Cronin was one of the brightest young players in the game.

In 1930 Cronin took his game up another notch, becoming the best shortstop and one of the best players in baseball. Joe hit .346 for the season, with 203 hits and 126 runs batted in. In fact, the baseball writers voted Joe the league’s MVP, ahead of Al Simmons and Lou Gehrig. It was not until 1931 that the writers’ award became the “official” MVP award, but Cronin was recognized in the press as the recipient in 1930. The Sporting News also gave Cronin its Player of the Year award. The Senators’ 94 wins were eight shy of the great Philadelphia Athletics’ 102-52 record.

Other than baseball, the principal excitement in Joe’s life was his relationship with Mildred Robertson. Per Joe Engel’s prophesy, Joe and Mildred had taken to each other right away, but it was anything but a whirlwind romance. Joe began by dropping in to the office more often than he needed to, but their courtship became more traditional in the spring of 1930 during spring training. As her uncle’s secretary, Mildred accompanied the team to their spring camp in Biloxi, Mississippi, every year. By the time the Senators returned from spring training to Washington in 1930, Joe and Mildred were dating twice a week when the team was home. Joe was adamant that the relationship remain a secret lest people write that Joe was trying to get in good with the boss.

On the field, Joe maintained his new plateau of excellence. In 1931 he hit .306 with 12 home runs and 126 runs batted in, as his club won 92 games, again well back of the Athletics. The next year he overcame a chipped bone in his thumb, suffered when he was struck by a pitch in June, to hit .318 with 116 runs batted in and a league-leading 18 triples. His club won 93 games, its third straight 90-win season and the third best record in team history. Nonetheless, after the season, Clark Griffith fired Walter Johnson, the team’s greatest hero. Griffith surprised everyone by selecting Cronin, just turning 26, to replace him. Not only did Cronin have to gain the respect of the veterans, he still had to worry about hitting and playing shortstop. Of course, there was the extra financial reward.

Cronin silenced all of the doubters in 1933 by continuing his fine play on the field (.309 with 118 runs batted in and a league-leading 45 doubles), while simultaneously managing his team to a pennant in his first season, still the youngest manager in World Series history. The Senators finished 99-53, and held off the Babe Ruth– and Lou Gehrig-led Yankees by seven games. In the World Series, they ran up against the New York Giants and their great pitcher Carl Hubbell, and fell in five games.

The next season, 1934, was a difficult one for Cronin and the Senators. The club dropped all the way to seventh place, at 66-86, and Joe took several weeks to get on track. At the end of May his average had dropped to .215, before he finally began to hit. He got his average up to .284 with 101 runs batted in, but as the team’s manager he was more distressed by the showing of his club. On September 3 he collided with Red Sox pitcher Wes Ferrell on an infield single and broke his left forearm, finishing his season. Cronin spent a week away from the bench, but returned on the 10th. A few days later, at the urging of Clark Griffith, Joe and Mildred pushed up their planned wedding to September 27 with a few days left in the season. After the ceremony, Joe and Mildred boarded a cruise ship for a honeymoon trip through the Panama Canal to Joe’s hometown of San Francisco.

When the Cronins landed in California, Joe had an urgent message to call Griffith. The news was a shock. Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey had offered $250,000 plus Lyn Lary for Cronin, and had agreed to sign Joe to a five-year contract as player-manager at $30,000 per year. It only needed Cronin’s OK. Joe realized what this would mean for Griffith, and also for himself and his new wife. He told Griffith to take the deal.

Two hundred fifty thousand dollars? In 1934, during the height of the Great Depression, this was an unfathomable sum. Cronin was the Alex Rodriguez of his time — his purchase price and contract became part of his identity. Stories about Cronin long after he had retired mentioned his 1934 purchase price.

When Cronin joined the Red Sox, dubbed the “Gold Sox” or the “Millionaires” by the nation’s press corps, the club was expected to win. When they did not win, the fans and press around the country typically blamed the high-priced help, including Cronin. Even worse, many of the veteran players Yawkey had acquired — ornery men like Wes Ferrell, Lefty Grove, and Bill Werber — did not like or respect their manager. This should not have been a big surprise; Grove did not like Connie Mack telling him what to do, and he certainly was not prepared to listen to the rich kid shortstop. The team was filled with temperamental head cases, and Cronin was younger than most of them.

On April 26, 1935, just a week into Cronin’s first season in Boston, the Senators beat Grove, 10-5, thanks to five Boston errors, three by Cronin, which led to eight unearned runs. Grove did not hide his irritation at each bobbled ball, or his anger when Cronin removed him in the seventh. When Cronin came to bat the next inning the Fenway Park crowd showered him with boos, causing Mildred to leave the park in tears. Cronin tripled, which provided a temporary respite.

It was not always this bad, but it was often bad enough. In July 1936, Ferrell called Cronin to the mound and told him he would not throw another pitch until the pitcher warming up in the bullpen sat down. A month later he stormed off the mound and back to his hotel room after a Cronin error. When informed by a reporter of his $1,000 fine, he shot back, “Is that so? Well, that isn’t the end of this. I’m going to punch Cronin in the jaw as soon as I see him.”4 A month later, Werber cursed at Cronin during a game and was ordered off the field. Cronin was not yet 30 years old when all this was going on.

Yawkey and general manager Eddie Collins were no help. Lefty Grove hunted and drank with the owner, who looked the other way when his star pitcher openly blasted Cronin in the press. Ferrell apparently never paid his fine for storming off the mound. The Red Sox continued to acquire controversial veterans, players who had had trouble with managers over their careers, and invariably they caused trouble with Cronin. When Collins finally succeeded in dealing Ferrell (along with his brother Rick, who caused no trouble) in 1937, the club acquired Bobo Newsom and Ben Chapman, two of the bigger managerial challenges in the game.

After a fine year at bat in 1935 (.295 with 95 runs batted in), Joe suffered through a frustrating season in 1936. The acquisition of Jimmie Foxx and others from the Athletics made the Red Sox a supposed pennant contender, but Joe’s injury-plagued season (a broken thumb limiting him to 81 games and a .281 average) helped the Red Sox finish a disappointing sixth. At this point many observers thought Joe, overweight, struggling in the field, and injured, might be through at just 30 years old.

Instead, Joe rebounded to hit .307 with 18 home runs and 110 RBIs in 1937, then .325 with 94 RBI and a league-leading 51 doubles in 1938. In the latter year, the Red Sox finished in second place with 88 wins, their most as a team in 20 years. On May 30 in Yankee Stadium, Joe got in a famous fight with Jake Powell on the field that carried over into the clubhouse runway after they had both been ejected. The runway was behind the Yankee dugout, and Joe had to hold off most of the Yankee team.

In 1938 Yawkey purchased the Louisville minor league club, perhaps partly in order to secure the rights to their young shortstop, Pee Wee Reese. After watching him play in a couple of exhibition matches against the Red Sox the next spring, Cronin was apparently not impressed and in July, coincidently or not, the Red Sox sold Reese to the Dodgers. Cronin was still a good player, and would be a better player than Reese for a few more years, but this transaction, in which his potential replacement was dealt, haunted Cronin in ensuing years.

Cronin started seven All-Star games, including the first three, and would have started a few more had the game existed earlier in his career. In the famous 1934 game, when Carl Hubbell struck out five Immortals in succession, Cronin was the fifth victim–after Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, and Al Simmons. Less remembered today is that Cronin managed the AL team, and that the AL won the game.

The Red Sox won 89 games in 1939, and Joe had another fine year — .308 and 107 runs batted in. Joe’s biggest problem in these years was the Yankees, who were one of history’s greatest teams. It was not any great shame to finish second to the Yankees in this era, and the Red Sox did so four times in five seasons beginning in 1938. Joe hit .285 with a career-high 24 home runs in 1940, then .311 with 95 runs batted in 1941.

After his All-Star season in 1941, he quietly stepped aside for rookie Johnny Pesky in 1942. Even with Pesky in the Navy for three years beginning in 1943, Cronin was mainly a utility infielder and pinch-hitter (setting a league record with five pinch home runs in 1943) during the war years. In April 1945 he broke his leg in a game against the Yankees, missed the rest of the reason, and hobbled away from his playing career.

In the heavily Irish culture of 1930s Boston, the Irish and personable Cronin remained personally popular with the fans and press. Even otherwise critical stories invariably mentioned what a swell guy he was. By the 1940s, Cronin was no longer the young upstart manager but was a veteran on a team that was developing young talent. The new generation, men like Ted Williams and Bobby Doerr, admired and respected Cronin.5

With his stars back and Cronin a full-time manager for the first time in 1946, the Red Sox cruised to the pennant but lost a seven-game World Series to the Cardinals. With most of the star players save Williams having off-years or hurting in 1947, the club fell back to third place. At the end of the season, Cronin took off his uniform for good, replacing the ill Eddie Collins as the club’s general manager.

In Cronin’s first act in his new role, he hired Joe McCarthy as his new manager. He followed that up with two big trades with the Browns that netted the club Vern Stephens, Ellis Kinder, and Jack Kramer, at the cost of a few players and $375,000 . These deals catapulted the team back into contention again, but they lost two heartbreaking pennant races in 1948 and 1949.

During Cronin’s 11-year tenure running the franchise (as general manager, president, and eventually treasurer), the team evolved from a contender to a middle-of-the-road club. The biggest problem, though by no means the only one, was the club’s failure to field any black players. The Red Sox famously had first crack at Jackie Robinson in 1945, and at Willie Mays in 1949. By 1958, Cronin’s last season as general manager, more than 100 blacks (either African-Americans or dark-skinned Latins) had played in the majors, 11 of whom went on to the Hall of Fame. None of the 100 played for the Red Sox.

Joe and Mildred had four children—Thomas Griffith (named after Yawkey and Clark Griffith, born 1938), Michael (1941), Maureen (1944), and Kevin (1950). They bought a house in Newton, just outside the city of Boston, in 1939 and settled there. In 1946, they bought a second house in Osterville, on Cape Cod, where the family spent most summers once the children got out of school. When Joe was no longer managing, he would work in the team offices during the week and spend most weekends on the Cape with his family.

During his years as GM, he had to deal with occasional controversies with Ted Williams, the mental breakdown of outfielder Jimmy Piersall, and the shocking death of young first base star Harry Agganis. He also had to deal with rumors that the Red Sox were going to move to San Francisco, or that he wanted to take over an expansion team in his native city. Joe would protest these rumors, saying that Boston, not San Francisco, was his home, the only home his children had ever known.

Meanwhile, Cronin’s power within baseball continued to grow. While running the Red Sox, he also served on the major-league rules committee, pension committee, and realignment committee, and represented Yawkey at all the league meetings. When AL President Will Harridge was first rumored to be stepping down in October 1956, Cronin was thought to be the obvious successor. When Harridge finally quit two years later, Cronin was quickly hired to succeed him.

In deference to Cronin, the league office was moved from Chicago to Boston. Cronin scouted the new offices himself, settling on a location in Copley Square. His principal role was to preside over league meetings, building consensus to solve the problems of the moment. The leagues had much more power than they do today—leagues had their own umpires, could expand or move teams without consulting the other league, could have their own rules, their own schedules. During his 15 years running the American League, Cronin oversaw the league’s expansion from eight to 12 teams, and orchestrated the relocation of four teams.

In 1966, while league president, Cronin hired Emmett Ashford, the first black major-league umpire, nearly seven years before the National League integrated. In a later interview with Larry Gerlach, Ashford praised Cronin for having the guts to hire him: “Jackie Robinson had his Branch Rickey; I had my Joe Cronin.”6

Cronin was twice a leading candidate for the commissioner’s job: in 1965, when Ford Frick resigned, and again when William Eckert was forced out in 1968. Cronin ran the American League until 1973, the year the league introduced the designated hitter rule, a rule he did not like but which he helped write. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn wanted to move the two league offices to New York, where the commissioner’s offices were. Cronin did not want to move, and he chose to retire instead. At the end of his final season, he was given the ceremonial title of American League chairman.

Joe spent a life in the game, and he was renowned for his good works outside the game. He set up the Red Sox’ initial connection with the Jimmy Fund, which became the team’s signature charity after its original sponsor, the Boston Braves, left town, and worked with the fund for many years. He received dozens of honors for his work outside the game.

Joe Cronin entered the Hall of Fame in 1956, with his longtime friend and rival Hank Greenberg—they were rivals as players, and at the time of induction they were rival general managers. The Red Sox retired his number 4 on May 29, 1984; on the same rainy evening they retired Ted Williams’ number 9—the first two numbers the Red Sox officially put out of service. Joe was dying of cancer, and the ceremony was pushed ahead to ensure that he could attend. He made it to that park that night, but was only able to wave to the crowd from a suite high above the field.

Williams was there, and praised his former manager and longtime friend. After waving to Joe, he told the crowd how important Cronin was to him. “Joe Cronin was a great player, a great manager, a wonderful father. No one respects you more than I do, Joe. I love you. In my book, you are a great man.”7

After a long battle with cancer, Joe passed away on September 7, 1984, leaving his beloved Mildred and their four children. He may be the least known of the honorees on Fenway Park’s right field façade, but no man had a greater impact on Red Sox history than Joseph Edward Cronin.

Notes

1 Bob Addie, “The Last Time Washington Won A World Series,” Washington Post, April 6, 1975.

2 Most of the narrative from this story is from the author’s Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press: 2008).

3 Mrs. Joe Cronin, “The Private Life of a Baseball Wife,” Liberty, May 2, 1936.

4 Washington Post, August 22, 1936.

5 See Mark Armour, Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball for numerous quotes from former teammates.

6 Larry Gerlach, The Men in Blue (New York: Viking, 1980): 285.

7 Peter Gammons, “Numbers That Count,” Boston Globe, May 30, 1984.

Full Name

Joseph Edward Cronin

Born

October 12, 1906 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

September 7, 1984 at Barnstable, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.