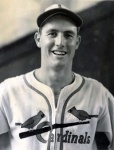

Mort Cooper

Mort Cooper was a big, burly pitcher who anchored the pitching staff for the St. Louis Cardinals’ three consecutive World Series teams from 1942 through 1944. Plagued by arm miseries his entire career, Cooper recovered from an elbow operation to lead the National League with 22 wins, 10 shutouts, and a 1.78 earned-run average in 1942 and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player. Following his third consecutive 20-win season, Cooper was involved in a bitter contract dispute and was traded to the Boston Braves in 1945. Soon thereafter his elbow problems re-emerged, and he never regained his form as one of baseball’s best pitchers. Enduring two additional operations and suffering from a life of excess off the field, Cooper was out of baseball by 1949.

Mort Cooper was a big, burly pitcher who anchored the pitching staff for the St. Louis Cardinals’ three consecutive World Series teams from 1942 through 1944. Plagued by arm miseries his entire career, Cooper recovered from an elbow operation to lead the National League with 22 wins, 10 shutouts, and a 1.78 earned-run average in 1942 and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player. Following his third consecutive 20-win season, Cooper was involved in a bitter contract dispute and was traded to the Boston Braves in 1945. Soon thereafter his elbow problems re-emerged, and he never regained his form as one of baseball’s best pitchers. Enduring two additional operations and suffering from a life of excess off the field, Cooper was out of baseball by 1949.

Morton Cecil Cooper was born on March 2, 1913, in Atherton, Missouri, a farming community about 25 miles east of Kansas City. His father, Robert, and his mother, Verne, were Missouri natives. Mort was the second oldest of six children, five sons and a daughter. (His brother Walker, also a big leaguer, was the third oldest.) Robert, a rural mail carrier and farmer, was a former sandlot pitcher who fostered in his boys an interest in baseball at a young age. Mort was a catcher in grade school, but when he injured his hand on a foul tip from a pitch thrown by Walker, they switched roles. Mort’s career as a pitcher was born. He attended William Chrisman High School in nearby Independence, Missouri, but dropped out by the age of 17 to work in construction to support his family.

Cooper’s high school didn’t field a team, and he played in the highly competitive Ban Johnson American Legion League in Kansas City. “I guess I was going pretty well,” Cooper said of the summer of 1932, when he pitched for a team managed by former big-league pitcher Ad Brennan and struck out 24 in a nine-inning game. “Brennan told Lee Keyser, the business manager of the Kansas City Blues, about me. I got a tryout in the fall of 1932.”1 Mort was invited to the team’s spring training in 1933 and was signed to a contract. The Blues’ manager, former Federal League center fielder Dutch Zwilling, was impressed by Cooper’s fastball, but recognized that the American Association, just one step below the big leagues, was not the place for a green 19-year-old right-hander to begin his professional career, and Cooper was optioned to the Des Moines Demons in the Class A Western League, where a series of events quickly tested his resolve. The Demons released him early in the season after he broke his leg on a liner back to the mound. Cooper caught on with the Western League’s Muskogee (Oklahoma) Oilers in late summer, but when the team could not meet its payroll obligations, he became a free agent. Joe Schultz, manager of the Springfield (Illinois) Cardinals and a St. Louis Cardinals bird-dog scout, had seen him pitch, and on Schultz’s recommendation, Cardinals boss Branch Rickey signed Cooper for $75 (two weeks’ back pay).2 To top it off, Mort told Rickey about his brother Walker (considered the better athlete of the two), and Rickey signed Walker to a contract. Mort finished the season with Springfield, his fourth uniform in five months.

Cooper spent most of the 1934 season with the Elmira (New York) Red Wings of the New York-Penn League after starting the season with the Columbus Redbirds of the American Association. Struggling with control, he walked 128 batters in 185 innings.

In the offseason Cooper had a scare that almost derailed his career and could have killed him. “An automobile wreck in the fall came near putting me on the shelf for keeps,” he told The Sporting News. “I broke my right shoulder and collarbone and four ribs.”3 Cooper struggled for the next two years from the effects of the injuries. He also gradually developed elbow pains that may have been caused by a change in his delivery to ease the pressure on his shoulder. With Columbus in 1935, Cooper logged just 101 innings while posting a 6-7 record.4 He began the following season with the Asheville Tourists in the Class B Piedmont League, making 11 relief appearances before being reassigned to Columbus. Manager Burt Shotton gave Cooper an opportunity to regain his arm strength and build his stamina. The big right-hander logged just 85 innings for the Red Birds, but exhibited better control and an exploding fastball. By the end of the season, rival manager Burleigh Grimes of the Louisville Colonels said Cooper was faster than Dizzy Dean.5 Convinced that Cooper was healthy, the Cardinals purchased his contract.

Cooper reported to his first big-league spring training in 1937 hoping to secure a spot on the Cardinals, whose staff had finished an uncharacteristic seventh in the league in team ERA the previous season. Manager Frankie Frisch was impressed with big Mort’s fastball, which The Sporting News called the “fastest in the Cardinals organization.”6 But Cooper’s tender elbow worsened after he was optioned to Columbus.7 Cooper seemed to take a step backwards, finishing with a 13-13 record and 4.10 ERA. A poor showing in the team’s seven-game loss to the Newark Bears in the Junior World Series (11 hits, seven walks, and eight runs in five innings) led to Cooper’s demotion to Houston in the Texas League for 1938.

Despite Cooper’s promise, he was an injury-prone pitcher with a losing record (41-45) heading into his sixth professional season, making his breakout campaign with Houston all the more unexpected. For a second-division club, Cooper won 13 games, led the league with 201 strikeouts, innings, and threw seven shutouts. At one point he pitched 34 consecutive scoreless innings. He credited pitcher Mike Ryba, a teammate at Columbus the season before, who showed him how to pitch a screwball.8

Cooper also possessed an independent streak and was determined not to let anything keep him from being promoted to the Cardinals. On August 13 he refused to accompany the Houston team on a road trip.9 Claiming that his ailing arm needed medical attention, Cooper went back home to Missouri. Houston president Fred Ankenman suspended him. Branch Rickey, who needed a strong right-handed presence in the Cardinals’ starting rotation after Dizzy Dean suffered a career-altering injury in the 1937 All-Star Game, intervened and called Cooper up to the Cardinals when the roster expanded in September. Later Cooper justified his actions, saying, “I was pitching a lot and knew the Cardinals would call me in after the season closed in the Texas League. Had I reported to the Cards late in 1938 with a bum arm, my chances of sticking would be hurt.”10

Cooper made an auspicious big-league debut by pitching a three-hitter to defeat the Philadelphia Phillies, 3-2, in Shibe Park on September 14. (He also issued a career-high eight walks.) He made three more appearances and, relying primarily on his fastball, finished with a 2-1 record. He attributed his heater’s effectiveness to the way he snapped his wrist as he released the ball. “If I didn’t pop the wrist, I wouldn’t be faster than any infielder,” he said.11

Cooper began his first full season with the Cardinals as a spot starter and reliever. He struggled until just before the All-Star break, when he earned a victory by tossing three scoreless innings in relief and then pitched his first complete game of the season, a six-hit win against the Pirates, to improve his record to 4-3. Given a chance to start regularly, Cooper fulfilled his promise, winning eight of 11 decisions and finished 12-6. Only the Dodgers’ Hugh Casey (15 victories) had a better rookie season.

The Cardinals and Cooper again got off to sluggish starts in 1940. Team owner Sam Breadon had little patience with managers who did not produce immediate results, and with the team 14 games below .500, he fired Ray Blades. New manager Billy Southworth, an agreeable and communicative skipper, and a fatherly figure to his players, instituted a platoon system and juggled his pitching staff to create the best matchups. The team responded by going 69-40 to finish in third place. But Cooper was inconsistent. Through August 6 he won just six games and lost eight. He caught fire in the last seven weeks, completing seven of ten starts and tossing two six-hit shutouts. Though he finished with a losing record (11-12), Cooper was a workhorse, logging 230 2/3 innings and completing 16 of 29 starts. With a surfeit of major-league-ready pitchers in the minors, the Redbirds were on the verge of a decade-long period of pitching excellence.

Copper inaugurated the 1941 season with an overpowering five-hitter over the reigning World Series champion Cincinnati Reds on April 16. Then disaster struck. Cooper complained of elbow tenderness after an ineffective outing against the Reds on May 29 (five runs in 3 2/3 innings), and lasted just 11 innings (surrendering 17 hits and 13 earned runs) in his next three starts. Despite a complete-game victory over the Phillies on June 17, Cooper was removed from the rotation. The team physician, Dr. Robert Hyland, discovered bone spurs and performed surgery on June 23.12 Cooper returned on July 27, and was shelled for four runs in a third of an inning on July 27. Still, Southworth pinned his pennant hopes to his big right-hander. Often pitching on short rest, Cooper started eight times in August, wining six. But in September the normally hot-hitting Cardinal batters went cold, and Cooper, worn out from the previous month and complaining once again of pain in his elbow, lost all four of his decisions that month. The streaking Brooklyn Dodgers won 40 of 58 games and took their first pennant since 1920. Cooper finished with 13 wins and nine defeats.

As the 1942 season began, there was legitimate concern that Cooper had lost the edge off his fastball. A poor showing as the Opening Day starter elevated the tensions, but they were diminished by a three-hit shutout of Cincinnati in his next start. He began May by pitching five consecutive complete games (wining three). But Mort was just warming up. In the best month of his career, he won all seven of his starts in June, tossed six complete games and four shutouts (including three in a row), and posted a minuscule 0.72 ERA. Notwithstanding his success, the Cardinals lagged nine games behind the Dodgers. “Cooper has come on so spectacularly and unexpectedly that the opposition doesn’t even know what his best pitch is,” wrote New York sportswriter Stanley Frank.13 Cooper’s diverse repertoire was confounding. Bill McKechnie, manager of the Reds, said the slider was his best weapon. Reds pitcher Paul Derringer said it was a screwball.14 Cooper had a different explanation: “I’ve stopped relying on my high hard one in every pinch. [My] forkball is not only a fine change of pace, adding to the effectiveness of my curve and fastball, but it’s good enough to fool hitters.”15

Cooper, who wore number 13, was not a superstitious player, but after winning just twice in six weeks, decided to don jersey number 14 on August 14 in search of his 14th win. The result was a two-hit shutout of the Reds, and Cooper decided to wear the jersey number corresponding to each win he needed on his march to 20 wins. During the last six weeks of the season, big Mort won nine of ten decisions, completed nine of ten starts, tossed four shutouts, and posted a 1.13 ERA.

Cooper was at his best against the archrival Dodgers, beating them five times against one loss. He faced off against Brooklyn’s ace, Whit Wyatt, in some of the most important games of the season, including a two-hitter on May 20 (one of his four two-hitters for the season) and a three-hitter on September 11. But the most memorable was an extra-inning affair on August 25 at Sportsman’s Park. Cooper and Wyatt were locked in a scoreless duel through 12 innings. Each gave up a run in the 13th, but Cooper emerged as the victor, 2-1, in a 14-inning masterpiece when Marty Marion scored the winning run on Terry Moore’s single.

On the strength of their dominant pitching staff, which set a big-league record with a 2.55 team ERA, the Cardinals won 68 of 89 games (.764) in the last three months of the season to overtake the Dodgers on September 13 and win the pennant by two games with a team-record 106 wins. Cooper was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player on the basis of his league-leading 22 wins, 1.78 ERA, and ten shutouts.

Cooper struggled against the Yankees in the World Series, leading sportswriter Dan Daniel to call him a “flop.”16 In Game One he yielded ten hits, walked three, and surrendered five runs (three earned) in 7 2/3 innings, and was collared with the loss. He fared worse in Game Four, giving up seven hits and five runs in 5 1/3 innings, but the Cardinals rallied in the seventh and won the game. Johnny Beazley won Game Five to secure the Redbirds’ first championship since 1934.

As the Cardinals ran away with the pennant again in 1943, besting the Reds by 18 games, the robust Cooper was the NL’s most dominant pitcher. He led the league in victories (21), and ranked second in ERA (2.30), complete games (24), strikeouts (141), and shutouts (6). He accomplished all of this while complaining of a sore arm the entire season and freely admitting that while pitching he chewed aspirin by the dozen to numb the pain. Cooper tossed consecutive one-hitters on May 31 against the Dodgers and the Phillies on June 4. On July 18 he pitched a complete-game victory against the Pirates in the first game of a doubleheader, then pitched two hitless innings of relief to secure the victory in the second game. On August 24 he pitched a ten-inning, 1-0 shutout over Boston, and on September 17 he hurled a ten-inning five-hitter to defeat the Cubs, 2-1. “To southpaw batsmen,” wrote Jack Cuddy of the United Press, “[Cooper] feeds them screwballs, keeping them on the outside so they can’t be pulled to leftfield. Right-handed hitters get the fastball and forkball. The latter approaches the plate in a drunken fashion like a knuckler’s butterfly pitch.”17

In the World Series, Southworth started Max Lanier instead of Cooper in Game One. “I decided to take the pressure off him,” the manager said.18 Cooper had been derided by the New York press for his failures in the previous World Series and his poor performance as the loser in the All-Star Game. Hours before World Series Game Two in New York, Cooper learned that his father had died. Pitching to honor his mentor, Mort responded with the Cardinals’ only Series victory. In Game Five he started strong, setting a Series record by striking out his first five batters, but yielded a two-run homer to Bill Dickey in the seventh. Spud Chandler gave the Yankees the crown with his 2-0 shutout.

In 1944 Cooper matched his career high with 22 wins. He had a 2.46 ERA and led the league with seven shutouts. The Cardinals won 105 games, becoming the first NL team to win 100 games three seasons in a row and took the pennant by 14½ games. In his final start of the year, on September 24, Cooper pitched a career-high 16 innings, yielding 19 hits in a victory over the Phillies. (The Phils’ Ken Raffensberger also went the distance, but surrendered a game-winning home run to Whitey Kurowski in the 16th.)

In the “Trolley World Series” of 1944, the Cardinals faced the surprising St. Louis Browns. In Game One Cooper surrendered just two hits in seven innings, but one was a two-run homer by George McQuinn that gave the Browns a 2-1 victory. In Game Five, behind solo home runs by Danny Litwhiler and Ray Sanders, Cooper was dominant, striking out 12 in a seven-hit shutout. Victory in Game Six gave the Cardinals their second title in three years.

A week before Opening Day in 1945, brothers Mort and Walker Cooper engaged in a “strike” against club owner Sam Breadon for his penny-pinching ways and threatened to boycott the team’s season-opening series in Chicago. Mort had signed a contract in the offseason paying a reported $12,000 only after Breadon told him the team was limited by the federal Wage Stabilization Act of 1943, which prohibited teams from paying any player more than their highest paid player earned in 1942. For the Cardinals that was Terry Moore’s $12,000 salary. Cooper learned near the end of spring training that Marty Marion had received an exception, and he left camp. “We will not accept less than $15,000 salary, and we fail to understand why the [championship] St. Louis club … should be in the second division in relation to salary ‘ceilings,’” he said.19 But the brothers capitulated and were with the team on Opening Day. Walker was inducted into the US Army in late April. On May 23 the Cardinals traded Mort to the Boston Braves for pitcher Red Barrett and $60,000. Cooper shut out the Reds in his first start as a Brave, and logged complete-game victories in his next three starts. Then his elbow miseries re-emerged, limiting him to six ineffective starts and nine relief appearances before he had a second operation in late August to remove bone spurs from his elbow. His only appearance after that was two scoreless innings of relief in the last game of the season.

Cooper began the 1946 season unable to straighten his arm and with his career in doubt.20 His new manager, Billy Southworth, whom the Cardinals had fired after their second-place finish in 1945, gave him extra time between appearances; the 33-year-old responded by winning 13 games. Cooper, Johnny Sain (20-14), and rookie Warren Spahn (8-5) led the Braves to 81 wins, their second-best season in 30 years.

Despite Cooper’s promising comeback in 1947, his end came quickly. He had always battled his weight, but counted on his arm and a rigorous spring workout to get him ready for the season. However, his arm was no longer the same after the two surgeries, and his weight had ballooned to over 250 pounds at the start of camp in 1947. After ten mainly ineffective appearances, Cooper was sent to the New York Giants for pitcher Bill Voiselle and cash. He lost five of his first six starts, then had a third elbow operation to remove bone chips. He finished the season with a dismal 3-10 record and 5.40 ERA. At spring training in 1948, Cooper, overweight and battling the effects of an excessive lifestyle, announced his retirement.

Cooper’s personal life stood in stark contrast to the control he exhibited on the mound. In 1933, at the end of his first year in professional baseball, he married Mary Bunyar, a resident of Jackson County, where he lived. She died in a car accident in 1936, and soon afterward Cooper met 19-year-old Bernadine Owen, a friend of Walker’s wife. They were married three weeks after they met. Bernadine and Mort spent the baseball season together, but returned to their roots in Independence in the offseason. They had one child, Lonnie, whom Mort named in honor of his good friend and teammate Lon Warneke. To the nation, the Coopers seemed an ideal couple. Mort was a star and earned good money; Bernadine was attractive and played the role of supportive wife. When Bernadine filed for divorce in November 1945, it made national headlines.21 She charged that Cooper had a violent temper and drank excessively and demanded custody of their son. Their divorce proceedings played out publicly in the following years. In court proceedings, Mort revealed that he had squandered all his earnings from the Cardinals. His business investments, from a nightclub and liquor store in Independence, and excessive spending at home, such as a $2,500 basement bar, left him completely in debt and unable to pay $100 per month alimony and $200 per month in child support. He had enjoyed the bright lights of baseball stardom while shrugging off family and financial problems.

Cooper’s fall from grace seemed sudden and unexpected, and his troubles worsened as his career was derailed by injuries, alcoholism, and poor physical shape. The nadir came in October 1948 when he was arrested in St. Louis for passing three bad checks. Sam Breadon, who had sold the Cardinals after the 1947 season, came to his player’s rescue and posted a $2,000 bond for his release. “[Cooper] doesn’t have a cent of his baseball earnings left,” said Breadon.22 Cooper seemed oblivious to his personal and professional situation. “This has taught me a lesson,” he said matter-of-factly. “I hope to find a baseball job for I feel I have five or six more years of good baseball in me.”23 He spent the 1948 season playing as a semipro in Kansas City.

Despite their contractual differences, Breadon had a soft spot for Mort. Dying of prostate cancer, Breadon asked Philip Wrigley, owner of the Cubs, for one last favor. In what The Sporting News later described as a “reckless bet,” the Cubs signed Cooper in January 1949.24 Coming into a game in relief on May 7, he gave up a walk, threw a wild pitch, yielded a single, and finally, on what turned out to be his last pitch in the big leagues, surrendered a towering home run to Duke Snider.25 He was unceremoniously released a week later. He attempted one last, unsuccessful comeback, in the Southeastern Saskatchewan Senior Independent League after his release.

Cooper won 128 games in his 11-year big-league career, with a 2.97 ERA. In his six-year minor-league career, he won 54 games.

Cooper’s fortunes faded quickly in retirement. Legal problems with his second wife persisted into the early 1950s, by which time he and his third wife, Viola Dee (whom he married in 1946), had settled in Houston. His health, too, was deteriorating quickly. In 1951 he was hospitalized for liver problems. In Houston he occasionally worked at baseball camps, briefly scouted for the Cardinals, tried his hand at running another tavern, Mort Cooper’s Dugout, and worked as a night watchman for the Sheffield Steel Company in Houston. While traveling, he was admitted to St. Vincent’s Hospital in Little Rock, Arkansas, suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, pneumonia, diabetes, and a staph infection. After three weeks in the hospital, Cooper died on November 17, 1958. He was 45 years old. He was buried at Salem Cemetery in Independence.

Last revised: April 12, 2023 (zp)

Sources

Newspapers

New York Times

The Sporting News

Online sources

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.com

Other

Mort Cooper player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Notes

1 The Sporting News, August 24, 1939, 3.

2 The Sporting News, January 31, 1946, 4.

3 The Sporting News, September 22, 1938, 14.

4 The Sporting News, February 20, 1936, 8.

5 The Sporting News, September 24, 1936.

6 The Sporting News, March 25, 1937, 5.

7 The Sporting News, May 27, 1937, 13.

8 The Sporting News, August 24, 1939, 3.

9 The Sporting News, September 22, 1938, 14.

10 The Sporting News, August 24, 1939, 3.

11 The Sporting News, September 22, 1938, 14.

12 The Sporting News, July 3, 1941, 3.

13 Stanley Frank, “Stanley Frank Reports: Arm Operation Made Ace Pitcher of Cooper,” undated New York Post article in Mort Cooper player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

14 Ibid.

15 Hy Turkin, “Mort the Mortifier,” New York Daily News, September 28, 1942, Mort Cooper player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

16 The Sporting News, October 15, 1942, 4.

17 Jack Cuddy (United Press), “Mort Cooper Hurls One-Hit Contest,” Ogden (Utah) Standard Examiner, June 5, 1943, 5.

18 The Sporting News, December 8, 1943, 18.

19 The Sporting News, April 19, 1945, 6.

20 The Sporting News, March 12, 1947.

21 The Sporting News, November 15, 1945.

22 The Sporting News, October 27, 1948, 19.

23 “Mort Cooper Free on Check Charges,” United Press, Milwaukee Journal, October 29, 1948, 6.

24 The Sporting News, March 16, 1949, 24.

25 The Sporting News, August 11, 1948, 37.

Full Name

Morton Cecil Cooper

Born

March 2, 1913 at Atherton, MO (USA)

Died

November 17, 1958 at Little Rock, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.