Danny Tartabull

For several years baseball was very, very good to Danny Tartabull. The game gave him honors and recognition, though not quite as much as he thought he deserved. Baseball paid him millions of dollars, enabling him to live a luxurious life style that most people could barely imagine. But it wasn’t enough. He was unable or unwilling to support his youngest sons. His photograph had once graced the cover of Sports Illustrated for Kids. More recently it has appeared on Most Wanted posters in post offices throughout the state of California.

For several years baseball was very, very good to Danny Tartabull. The game gave him honors and recognition, though not quite as much as he thought he deserved. Baseball paid him millions of dollars, enabling him to live a luxurious life style that most people could barely imagine. But it wasn’t enough. He was unable or unwilling to support his youngest sons. His photograph had once graced the cover of Sports Illustrated for Kids. More recently it has appeared on Most Wanted posters in post offices throughout the state of California.

Danilo Tartabull Mora was born on October 30, 1962, in San Juan, Puerto Rico, a son of Antonia Maria Mora and José Milage Tartabull Guzman. His family had been prominent in Cuba until Batista was overthrown by Fidel Castro in 1959. Maria’s father had owned a sugar factory in Cienfuegos, José’s father was a college professor; his grandfather was a judge.1 Factory owners and supporters of the Batista regime did not fare well under the new order.

José Tartabull was a professional baseball player. After five years of semipro and minor-league experience, he made his major-league debut for the Kansas City Athletics a little more than six months before Danny was born. During the baseball season, the family lived wherever José’s club was based. They spent their winters in South Florida. Danny’s earliest memories were of romping in the ballpark in Winter Haven during spring training.

As the son of a ballplayer, Danny learned the game of baseball at a very early age. During the summer of 1967, the Tartabulls lived in Brookline, Massachusetts, while José played for the Boston Red Sox. There was a park near their residence, where José was often seen playing catch with his four-year-old son.2

The youngster developed his skills on the sandlots of Miami. “I grew up in baseball because of my father, not because of Miami,” he said. “I thought everybody’s dad went to the ballpark every day at 3 o’clock and played a game of baseball.”3 Danny didn’t just play baseball at 3 o’clock. Sometimes he played in three leagues at once. He could play a game in the morning, another after lunch, and a third in the evening. His teammates on one Little League team included José and Ozzie Canseco, Rafael Palmeiro, and Junior Valdespino. Who was the star? “I hate to say this,” he said, “but I was. I think my development was quicker because of being around the game more than all of them.”4

In 1978 15-year-old Danny played American Legion baseball in suburban Miami for Hialeah Post 32 and helped the club win the American Legion World Series. He played high-school ball for Miami’s Carol City High School. At age 17 he was selected, as a second baseman, out of high school by the Cincinnati Reds in the third round of the 1980 amateur draft.

The Reds sent Danny to Billings, Montana, in the Pioneer League. He hit .299 in 59 games for the Mustangs in 1980 and played mainly at third base (34 games), although he logged one game at second and 22 in the outfield. In 1981 Tartabull hit .310 for the Tampa Tarpons in the Class-A Florida State League, while playing 46 games at second base and 78 at third. He led the league in batting and doubles, was tied for fourth in home runs, and tied for third in triples and RBIs. He was named the circuit’s Player of the Year. Hal Keller, Seattle’s director of player personnel, was enthusiastic about the youngster. He told a reporter for The Sporting News, “I must have checked with a dozen people who saw this guy play and there was little doubt he could play in the big leagues. I think he’ll be a second baseman, but as a fallback, he has enough pop to be a legitimate third baseman.”5

In 1982 Tartabull hit a career-low .227 for the Waterbury Reds in the Double-A Eastern League, while playing exclusively at second base. That was his final season in the Cincinnati farm system, as the Seattle Mariners chose him on January 20, 1983, as a compensation pick after the loss of Floyd Bannister to free agency. At that time clubs could prevent the loss of players to the draft by putting them on a “protected list.” Years later, Cincinnati’s farm system director said the failure to protect Tartabull was the most regrettable decision the Reds had made in his quarter-century with the team.6

In 1983 the Mariners shipped Tartabull to Chattanooga, their affiliate in the Double-A Southern League. He hit .301 for the Lookouts and played the entire season at second base. The following year the Mariners promoted him to Salt Lake City in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League and switched him to shortstop He hit .304 for the Gulls, earning a late-season callup to the big leagues.

Tartabull made his major-league debut on September 7, 1984, at Royals Stadium in Kansas City. He was 21 years old, stood 6-feet-1, weighed 185 pounds, and batted and threw right-handed. He entered the game as a pinch-runner for Alvin Davis in the ninth inning of a 5-3 loss to the Royals. His next appearance came in Seattle’s Kingdome on September 11. The Mariners and the Texas Rangers were tied, 3-3, in the bottom of the ninth inning. The bases were loaded with two outs. Tartabull hit a game-winning RBI single. In his first major-league at-bat he had a walk-off hit.

On February 18, 1984, Danilo Tartabull and Monica Anita Cusseaux were married in Hillsborough County, Florida. In compliance with Florida law at the time, the race of the bride and groom was shown on the marriage certificate. Both were identified as “black.” The marriage lasted about 5½ years. The couple divorced in Pinellas County, Florida, on August 4, 1989.

In 1985 Tartabull played a few major-league games for Seattle, mainly at shortstop, but he spent most of the season with the Calgary Cannons, who had replaced Salt Lake City as the Mariners’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. What a season he had! He hit .300, scored 102 runs, and batted in 109, the first time he had topped the century mark in either category. He experienced a real power surge, blasting 43 home runs. In five previous seasons in professional baseball, Tartabull had never clouted more than 17 homers in a season. He ranked second in the league in runs scored, led in both home runs and runs batted in, and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player.

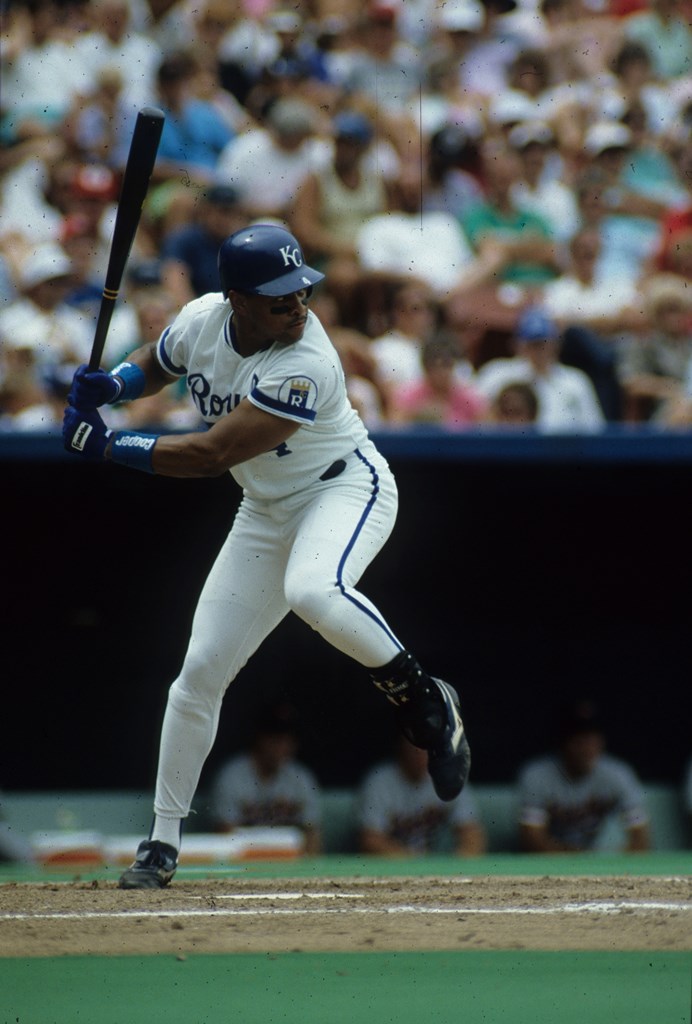

After that performance, Tartabull could no longer be kept down on the farm. He never returned to the minor leagues, playing 12 more years at the major-league level. In 1986 Tartabull hit .270 with 25 homers for the Mariners. He ranked fifth in voting for the American League Rookie of the Year Award. Although he had been primarily an infielder throughout his earlier career, Seattle converted him into an outfielder and he roamed the outer garden the rest of his career. On December 10, 1986, the Mariners traded Tartabull along with minor-league pitcher Rick Lueken to the Kansas City Royals for outfielder Mike Kingery and pitchers Scott Bankhead and Steve Shields. Many Seattle fans were stunned by the trade, as they envisioned the young power hitter as a possible superstar of the future.

Tartabull made an immediate impact in Kansas City. In 1987 he hit .309 with 34 home runs and 101 RBIs. The next year he hit .274 with 26 homers and 102 runs batted in. Those performances earned him a big boost in pay. In 1989 he received over a million dollars for the first time in his career. He got nice raises the next two seasons, even though his productivity fell off slightly. However, he came back in 1991 with one of his best years ever. He hit a career-high .316 with 31 home runs and 100 runs batted in. He led the league with a .593 slugging percentage. He was twice named the American League Player of the week, once in June and once in July. Tartabull was selected for the 1991 All-Star Game.

Despite his success at the plate, Tartabull was not universally popular among his teammates. Some Royals thought Tartabull had a bad attitude. He was regarded as aloof, arrogant, selfish, interested only in his own hitting, not a team player, and a lackadaisical outfielder. Some resented his ostentatious style of living. He certainly showed off his new-found wealth. One example was how he splurged on his proposal to his girlfriend, Kellie Van Kirk. One April night in 1989, he sent a limo to pick up Kellie, along with a dozen roses, and a note requesting that she wear his favorite dress and asking that she go with the driver to Wyandotte County Lake, just across the state line in Kansas. When she arrived, she found he was waiting for her in a rented tuxedo, accompanied by caterers and a harpist. A four-course meal with champagne was served, while the harpist played romantic music. After the meal Danny suggested they go for a walk up a nearby hill. When they reached the crest of the hill, they saw a fireworks display that spelled out in letters 25 feet high, “Kellie, will you marry me?” She said. “Yes.” Tartabull said, “I’ll get married, I’ll have kids, and I’ll have a lot of things happen in my life, but that was a night I’ll treasure as long as I live.”7 Little could he imagine the things that would happen in his life.

After the wedding, Kellie and Danny lived during the offseason in a lavish mansion in the Santa Monica Mountains near Malibu, California. The couch was made of Italian leather, the sound system was floor-to-ceiling, the works of art were well-chosen, the 300-gallon saltwater tank was filled with exotic fish, the wine cellar was stocked with expensive fine wines, including 50 bottles of 1985 Chateau Lafite Rothschild, valued at $450 each. “I enjoy making other people feel great,” he said. “I want to make my wife happy, and my kids happy, get them things they want.”8 In view of what happened later, how ironic were those words! In the garage were parked two luxury automobiles. The vanity license plates reflected the ego and talents of their owner: SLUGGER and I CAN HIT.

Tartabull professed to not know why some of the Kansas City players found him aloof and a poor teammate. He thought perhaps it was jealousy. “I don’t know where it came from, and I don’t waste my time trying to find out. It’s not true. I brush it off like dust.”9 Kellie said, “It bothers me more than Danny. I know he’s none of those things I hear about, not even close. He’s a family man, a person who enjoys having fun, going to nice restaurants. He always includes my whole family in the things we do.”10 Kellie accompanied Danny on every road trip. When he was with his wife, he wasn’t with his teammates, contributing to the feeling that he was aloof.

Tartabull professed to not know why some of the Kansas City players found him aloof and a poor teammate. He thought perhaps it was jealousy. “I don’t know where it came from, and I don’t waste my time trying to find out. It’s not true. I brush it off like dust.”9 Kellie said, “It bothers me more than Danny. I know he’s none of those things I hear about, not even close. He’s a family man, a person who enjoys having fun, going to nice restaurants. He always includes my whole family in the things we do.”10 Kellie accompanied Danny on every road trip. When he was with his wife, he wasn’t with his teammates, contributing to the feeling that he was aloof.

Tartabull thought the high opinion he had of himself was justified. “I’ve always felt I’m a great player. I am great. I know that in certain situations I can do things that a lot of other guys can’t,” he said. “Let’s say I do tell everyone that I’m great. What does that have to do with having a bad attitude?”11

At least one of Tartabull’s Kansas City teammates defended him. Brian McRae said, “Some people say he had a bad attitude. People think he is arrogant, but that’s just the way he is. Not everybody can be your normal run-of-the-mill person. He likes fancy cars, he likes dressing nice, he has a lot of nice jewelry. That might rub some people the wrong way, but that’s just Danny.12

Kansas City granted Tartabull free agency on October 28, 1991. Several clubs were interested in obtaining the services of the young star. During the early part of the recruiting process, the California Angels, Chicago White Sox, and the Texas Rangers appeared to the frontrunners. The White Sox dropped out of the bidding when Tartabull insisted on a five-year contract. Chicago general manager Ron Schueler said, “Five years is too long for me.”13

Tartabull had been the Angels’ primary target, but their ardor cooled when the club’s vice president, Whitey Herzog, became bitter about the way Tartabull’s agent, Dennis Gilbert, had behaved during earlier negotiations involving Bobby Bonilla. (Gilbert represented both Tartabull and Bonilla.) 14

Although they had not been mentioned among the early contenders, the New York Yankees made Tartabull an offer he couldn’t refuse. On January 6, 1992, he signed a five-year contract with the Yankees for $25.5 million, the most lucrative contract in club history to that point. He was guaranteed an additional $1.5 million in an endorsement clause that covered the life of the contract. “Texas and the Angels were both very attractive to me,” Tartabull said. “But the New York Yankees, man, they’re something else. How can you not get excited about that tradition? There’s a great mystique to it. Everyone and everybody would love to have that prestige.”15

Tartabull expected that playing for the Yankees would be a joyful experience, but fate deemed otherwise. He was hampered by injuries every year he was in pinstripes, never logging more than 138 games in a season for New York. Some Yankees officials thought, perhaps unfairly, that he should have played through his injuries.

At first Danny was thrilled at the opportunity to play in New York. He and Kellie purchased a home in Saddle River, New Jersey, within commuting distance of the city. When he signed with the Yankees, they had two children, Danica Janelle, 5, and Danny Jr., 4. Kellie was pregnant with their third child, Zachary, who would be born in Teaneck, New Jersey, on June 23. “New York is the greatest city in the world,” Tartabull said. “I can live here (in California) in the winter and play in New York during the season. It’s the ultimate.”16 In New York he and Kellie could attend the opera, see Broadway shows, and visit world-class art galleries. “You can’t do that in Kansas City or Seattle,” he said. “I’ve always been interested in culture. I like going to plays, my wife and I love the ballet, and we both love art. You can tell just walking through my house. We spend a lot of time in galleries.”17

The house in Malibu was nice, but Tartabull wanted bigger and better. He had some property in Rancho Santa Fe Farms in the San Diego area. He hired an architect and planned to spend $30 million to build an 11-room, 27,000-square-foot house next door to the home of pop star Janet Jackson. The house would feature a batting cage with a viewing platform, a saltwater aquarium, a scaled-down train to take the family or visitors on a tour of the estate, with stops at a game room, Tiki bar, basketball and tennis court, putting green, and an indoor/outdoor swimming pool, with a 14-foot waterfall, and a water slide descending from the children’s bedrooms. He planned to also have a sports training center, with an exercise room and a health bar, a two-story movie theater, a pinball and video arcade, and an aviary.18 How many of these plans actually came to fruition is not known.

Although he missed 39 games his first year in New York due to injuries (strained left hamstring, lower-back spasms), Tartabull was the Yankees’ most productive hitter with 25 home runs and 85 runs batted in. The next year he was even better with 31 homers and 102 RBIs. However, he was unable to match those figures again, and he never hit more than .266 in New York. He struck out more than 100 times each season he wore pinstripes, with his 156 K’s in 1993 being second highest in the league. Because of a shoulder injury, incurred when he was making a throw on July 15, Tartabull was unable to play in the field during the second half of the 1993 season, being restricted to the designated-hitter slot.

After the season Tartabull elected to have cosmetic facial surgery and then spend the first three weeks of November vacationing in Europe, delaying his shoulder surgery for more than a month. Dr. Frank Jobe performed the operation at Centinela Hospital in Inglewood, California.19 Some Yankee officials thought Tartabull should have given higher priority to the shoulder surgery.

In 1994 Tartabull played in only 104 games, mostly as a designated hitter. He hit .256, with 19 home runs and 67 RBIs. He appeared twice on the Seinfeld TV show and once on Married … With Children.

Unhappy with Tartabull’s attitude, the Yankees tried to trade him during spring training, 1995, but found no takers, even when they offered to eat as much as $2 million of his contract. On Opening Day the much-criticized slugger hit a homer and an RBI single. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner said, “I’m still disappointed in Tartabull. Very disappointed.”20

Upset by Steinbrenner’s criticism, in June Tartabull asked to be traded. He needn’t have bothered. The Yankees had been trying to unload him for months. “It’s easy for him to ask, but it’s not easy to move him,” general manager Gene Michael said. “Clubs don’t want to take that kind of money (Tartabull’s $5.3 million salary). I’ve tried to move him.”21

Disappointed with his performance, Yankee fans started booing Tartabull whenever he failed to deliver. Tartabull thought Steinbrenner encouraged the boos. The owner was famously hard to get along with, but Tartabull carried their feud to an extreme. His days in New York were numbered. The long-anticipated trade occurred on July 28, when the Yankees dealt the disgruntled slugger to the Oakland Athletics for veteran Ruben Sierra and minor-league pitcher Jason Beverlin. The Yankees sweetened the deal by agreeing to pay half of Tartabull’s salary. “I feel like I’ve been released from jail,” Tartabull said.22

With the deal completed, Tartabull was able to vent his bottled-up feelings. “It’s a zoo there. No I take that back; it’s a joke. The sad part is that the only reason for that is the owner. He wants to be the center of attention so bad he just destroys that team. It’s so hard for those guys to win because of that man. … The guys won’t say it on the record, but they’re just miserable there. … I’d still be there if it weren’t for George. I had no problems with anyone else, but when you’ve got an owner like him, he makes it impossible to play up to your capabilities. I mean why would an owner keep downgrading his own product? It’d be like Lee Iacocca telling people not to buy cars. That’s just stupid. He’s an idiot for doing that.”23

Tartabull played only 24 games for Oakland. On January 22, 1996, the A’s traded him to the Chicago White Sox for pitcher Andrew Lorraine and minor-league outfielder Charles Poe. The Sox had to pick up only half of his $5.3 million salary.

On January 31, 1996, Kellie gave birth to the family’s fourth child, Quentin Riley Tartabull. In 1996 Danny had a good season on the South Side of Chicago. Although he hit only .254, he clubbed 27 home runs and knocked in 101 runs. He became a free agent on November 18, and the Sox were willing to re-sign him only if he would accept a huge pay cut. He was unwilling to do so and went on the open market. Few clubs were interested in him. One exception was Philadelphia. Hal McRae, who had managed Tartabull one year in Kansas City, was now the Phillies hitting coach and lobbied on Danny’s behalf. Tartabull rejected the Phils’ first overture, saying he was insulted by the “lowball offer.”24 After months of negotiations and no better deals tendered, Tartabull signed with Philadelphia for $2 million on February 25, 1997.

On Opening Day, April 1, 1997, Tartabull was in the Phils’ starting lineup, playing right field and batting cleanup in a game at Dodger Stadium. During the game he fouled a pitch off his left foot. He was removed from the game and sat out the next three contests, thinking he had a contusion. He was back in the lineup for the games in San Francisco on April 5 and 7. He was unable to complete the latter game and was taken out in favor of Derrick May in the seventh inning. He didn’t know it at the time, but his major-league career was over at the age of 34. An MRI revealed that his foot was fractured, and he would be out for the season. For their $2 million investment, the Phils got virtually nothing in return. Tartabull drew four bases on balls and scored two runs, but he made no hits in his seven official trips to the plate.

The Phillies declined to renew his contract, and Tartabull opted for free agency on October 10, 1997. He worked out during the winter, getting himself in shape, and hoping for a return to the big leagues. The San Diego Padres offered him a minor-league contract, but he turned it down. His baseball career was over. He returned to California, and stayed out of the limelight for a few years.

The next time Tartabull was in the national news involved family problems. He and Kellie split up around 2007, and a family court judge ordered Danny to pay child support for the two youngest children, Zach and Quentin. (Having passed the age of 18, neither Danica nor Danny Jr. was entitled to support.) Both boys were star football players, Zach at Valencia High School and Quentin at Bishop Alemany High School in Mission Hills. Zach graduated from high school in 2010 and became a male model. Quentin graduated in 2014 and accepted a football scholarship at the University of California, Berkeley.

Tartabull fell far behind on his child-support payments. On January 24, 2011, he entered a no-contest plea to charges that he willfully disobeyed the court order.25 Zach had already reached the status of “emancipation” and Quentin would soon join him in that category. Danny would not be liable for child support in the future, but he was liable for payments missed in the past, amounting to $276,204.93. Tartabull was placed on probation, but he violated the terms of the probation. On May 2, 2012, he was sentenced to 180 days in the Los Angeles County jail. He failed to report to jail, and the court issued a warrant for his arrest with bail set at $200,000. When authorities were unable to locate him, he was declared a fugitive from justice.26

If anyone knew where Danny was hiding out, they were not talking. “Most Wanted” posters went up in California post offices in July 2013. It took four years before police found him — after Tartabull himself called to report that his car had been broken into. Police ran his name through the system and finally arrested him.27

When Danny Tartabull was a baseball star, he was called “The Bull.” Now he is called a “deadbeat dad.”

Last revised: August 1, 2017

This biography originally appeared in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández. It also appears in “Kansas City Royals: A Royal Tradition” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Joanne Hulbert, “Jose Tartabull,” https://sabr.org/bioproj/person,54213446.

2 Ibid.

3 Craig Davis, “Yanks’ Danny Tartabull Has $25.5 Million, Wants More: A World Series Paycheck,” Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), April 5, 1992.

4 Ibid.

5 Tracy Ringolsby, “No-Trade Clauses Create Contract Woes,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1983.

6 Mike Bass, “Cincinnati Reds,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1992.

7 “Best of Plans Made for Night to Remember,” Los Angeles Times, April 29, 1989; Bruce Newman, “Bright Light, New City,” Sports Illustrated, March 23, 1992: 76.

8 Michael Martinez, “Bronx Is Up, but Tartabull Will Take Manhattan,” New York Times, February 6, 1992.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Newman.

12 Ibid.

13 Joe Goddard, “Chicago White Sox,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1992.

14 Dave Cunningham, “California Angels,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1992.

15 Moss Klein, “Yanks Give Tartabull a Record Number,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1992.

16 Martinez.

17 Ibid.

18 “Yanks’ Danny Tartabull Building a $30 Million House in California,” Jet, May 11, 1992: 48.

19 Jack Curry, “Tartabull Has Operation Yanks Preferred,” New York Times, December 1, 1993.

20 Jon Heyman, “New York Yankees,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1995.

21 Jon Heyman, “New York Yankees,” The Sporting News, June 19, 1995.

22 Bob Nightengale, “Tartabull Loves New York but Loathes Steinbrenner,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1995.

23 Ibid.

24 https://cornerpubsports.com/2015/06/phillies-all-train-wreck-team.

25 Sam Gardner, “Call him Deadbeat Danny Tartabull.” foxsports.com/mlb/story/danny-tartabull-former-mlb-allstar-shows-up-atop-deadbeat-dad-list-n-la, July 9, 2013.

26 Ibid.

27 Pete Grathoff, “Ex-Royal Danny Tartabull forgets he’s a fugitive, calls police and is arrested,” Kansas City Star, July 28, 2017, https://www.kansascity.com/sports/spt-columns-blogs/for-petes-sake/article163946127.html

Full Name

Danilo Tartabull Mora

Born

October 30, 1962 at San Juan, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.