August 17, 1882: Radbourn The Slugger

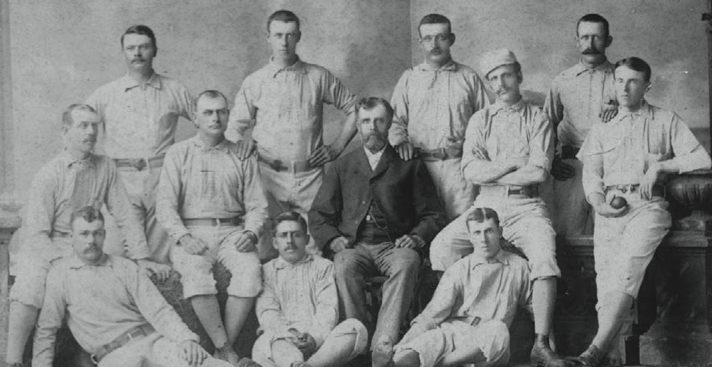

1882 Providence Grays. Back: Paul Hines, Jerry Denny, Hoss Radbourn, Jack Farrell. Middle: Tom York, Joe Start, Harry Wright, George Wright, John Ward. Front: Charlie Reilley, Sandy Nava, Barney Gilligan.

Harry Wright had seen dozens of electrifying games over the years, both as a star player and brilliant manager—leader of the undefeated Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1869 and the mighty Boston Red Stockings of the 1870s.

But moments after the contest of August 17, 1882, ended, Harry told reporters point-blank that it was the greatest baseball game he had ever witnessed.1

The game was an 18-inning, 1-0 masterpiece of wily and resolute pitching, gritty catching, and dazzling fielding during the era of barehanded play, when contests of such meticulous beauty were rare. And it was capped by a home run so dramatic that people talked about it for decades.

Some 1,200 fans paid their way into Providence’s Messer Street Grounds that hot Thursday afternoon.2 The third-place Detroit Wolverines, trailing by 4½ games in a still-competitive National League pennant race, were anxious to keep from slipping too far behind the first-place Providence Grays.

They sent out their ace, George “Stump” Wiedman, a 21-year-old en route to a career-high 25 wins. Providence manager Wright countered with John Montgomery Ward. Three years earlier, at 19, Ward had led the Grays to the pennant, but his young arm was already showing signs of serious wear, and he was being phased out as the club ace, replaced by the ornery Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, who was resting up on this afternoon by playing in right field.

Almost from the start, both clubs knocked on the door. In the fourth inning two Providence throwing errors landed Detroit’s speedy Ned Hanlon on second base, and when Martin Powell drove a single to center, Hanlon tore around third for home. But Paul Hines, a graceful fielder who was so deaf he needed an ear trumpet to hear anything, snatched up the ball and fired it to “the Spaniard,” the Grays’ Latino catcher Sandy Nava, who fell on the sliding Hanlon to retire the runner inches from the plate.3

On and on it went, inning after inning: fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth—still 0–0. That was, in part, because Grays third baseman Jerry Denny was snaring everything that came his way—barehanded, of course. One woman in attendance, noting that Denny seemed to catch the ball even with his knees, suggested he wear an apron.4

Nine innings down, a “second game” commenced with the opening of the 10th.5 “Neither Ward nor Wiedman appeared to have suffered much from the great strain imposed upon their pitching arms,” the Star observed. In those days, pitchers considered it unmanly to quit before the finish, no matter how many innings it took.

Meanwhile, in downtown Providence, 20 minutes away by horsecar, a throng had gathered around the first-floor window of the Providence Journal for telegraphed updates. As inning succeeded amazing inning, hundreds more jammed around the building, following the historic contest with rapt attention.6

With two out in the 15th, and a man on third, the Wolverines got a terrific chance to end it. As Hanlon broke for home, Detroit catcher Sam Trott lofted a pitch to deep right field. Radbourn turned and sprinted toward the fence, straining to reach for the escaping sphere. “The ball was over Radbourn’s head, and very nearly got by him,” the Star observed, but Charlie snared it out of the sky with his bare hands, and Detroit was out.

Then it was the Grays’ turn. Shortstop George Wright—Harry’s brother, nearing the end of a legendary career—hammered a drive to left field. In the corner was a gate, used to admit the posh carriages of well-heeled New Englanders who could, for a fee, park along the outfield fences. The ball scooted through this half-open gate, through a crowd of spectators and into the street, followed closely by left fielder George Wood, while Wright tore around the bases. Disappearing for a moment, Wood somehow recovered the ball— whether some accommodating fan tossed it to him is not clear—and heaved it over the gate to third baseman Charlie Bennett. Catcher Sam Trott got it just in time to tag out the luckless Wright. Providence sportswriters contended that veteran umpire George “Foghorn” Bradley should have declared the ball dead once he lost sight of it, returning brother George to third. But the bang-up play at home plate stood, and the Grays got nothing from their first extra-base hit but a heartstopping out.

On it went … 16th, 17th. Dusk was settling over the smoky city, and workers were already munching their supper. Radbourn, hitless in six attempts to that point, whacked a soaring fly toward the offending gate in left field, now safely shut.

“It was very close to the foul line and high in the air,” recalled Detroit second baseman Tom Forster, who lived until 1946, the last survivor of the great game. “George Wood could have caught it if there hadn’t been a fence in the way. To me it looked as if it came down foul outside the fence. But the umpire, Foghorn Bradley, waved me away. He said it was a fair ball crossing the fence.”7

Even Radbourn, a notoriously cantankerous fellow who would enter the Hall of Fame on the strength of his pitching—most notably his astonishing 59 wins in 1884—could not suppress a grin. “It was laughable to see Rad smile as he saw the ball moving over the left field fence,” the Telegram noted.

The telegraph clicked out the news to the hundreds downtown, setting off “deafening applause.”8 Back at the ballpark, people cheered wildly, filling the air with hats and pouring onto the field. “Everybody shook hands with the members of the nine, with Manager Wright, with their neighbors, and then went out and shook hands with themselves,” the Star reported.

The Telegram called it “the most beautiful base ball game in the history of the League.” It was “one long to be remembered by those so fortunate as to be present,” the Journal added—a sound prediction, because, for years, people talked about the 18-inning scoreless tour de force, broken at last by a clout from the bat of the greatest pitcher of the age.

Notes

1 Providence Morning Star, August 18, 1882.

2 Providence Morning Star, op. cit., reported 1,200. The Providence Evening Telegram, August 18, 1882, put the number at “about 1,400.”

3 Providence Morning Star, op. cit, refers to Nava as “the Spaniard” in its game account.

4 Providence Evening Telegram, op. cit, cites the apron quip.

5 Providence Morning Star, op. cit., refers to “second game.”

6 Providence Journal, August 18, 1882.

7 Brandt, Bill. Do You Know Your Baseball? (A.S. Barnes and Company, New York, 1947), p. 37.

8 Providence Journal, op. cit.

Additional Stats

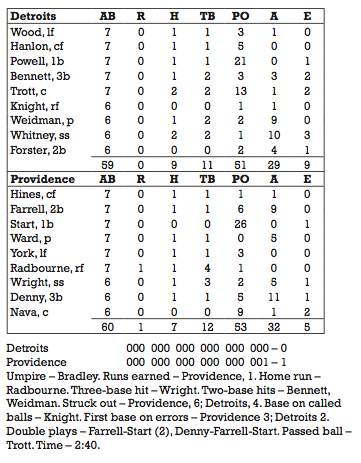

Providence Grays 1

Detroit Wolverines 0

At Messer Street Grounds

Providence, RI

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.