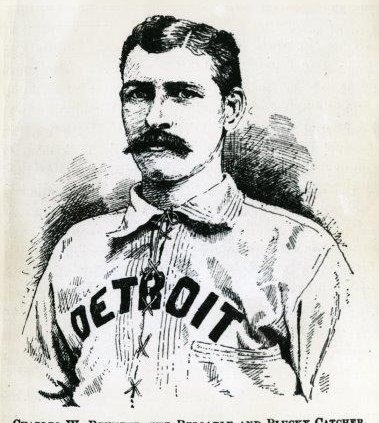

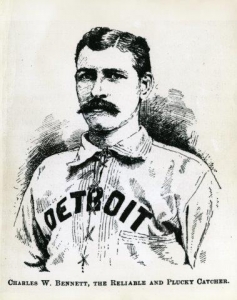

Charlie Bennett

When asked to name the best catchers of the nineteenth century, most baseball historians wouldn’t have to name very many before they mentioned Charlie Bennett, a fan favorite who was admired for his intense toughness and true love of the game. He was one of the most durable and best defensive catchers during an era when catchers lacked the benefit of large padded catcher’s mitts and modern protective equipment. He often played through injuries and took the punishment that resulted in battered hands, mashed fingers, and broken ribs in a manner that honored the game and the catching profession. In a similar manner, his dignified response to a tragedy that ended his career “elevated him to near-sainthood” among baseball fans across America.1

When asked to name the best catchers of the nineteenth century, most baseball historians wouldn’t have to name very many before they mentioned Charlie Bennett, a fan favorite who was admired for his intense toughness and true love of the game. He was one of the most durable and best defensive catchers during an era when catchers lacked the benefit of large padded catcher’s mitts and modern protective equipment. He often played through injuries and took the punishment that resulted in battered hands, mashed fingers, and broken ribs in a manner that honored the game and the catching profession. In a similar manner, his dignified response to a tragedy that ended his career “elevated him to near-sainthood” among baseball fans across America.1

Charles Wesley Bennett was born in New Castle, Pennsylvania, on November 21, 1854. New Castle at that time was a town of just over 1,600 inhabitants and a stop on the Western Pennsylvania canal system. He was the eighth of 11 children born to Silas and Catherine (Nickols) Bennett. Silas, a native of Connecticut, was a tinner and operated a hardware store in New Castle. When not playing baseball, Charlie helped his father in his shop.

Bennett began his career in Organized Baseball with the Neshannock team in the Pennsylvania League. He played with the team from 1874 to 1876. It was said he “broke the directors because of the number of balls knocked into the river.”2 Originally an infielder who divided his time between second, third, and shortstop before becoming a catcher, Bennett recalled the genesis of this transition in a 1908 interview with sportswriter George R. Pulford.

“When we played Beaver I noticed that their catcher stood up close behind the bat. You know in those days the catcher used to stand back and take the ball on the bound. But this fellow stood up there and grabbed the ball barehanded, and our fellows didn’t steal many bases.

“Well, we were playing one day after this, and our opponents stole bases right along. I told our catcher to go up behind the batter but he refused. ‘Not me,’ he replied. ‘If you want to try it, go ahead. I think too much of my hands.’

“Well, I went behind the bat and caught out the game and no more bases were stolen. I like the position, because it kept me doing something all the time, and from then on I caught.”3

At the end of the 1876 season, the 22-year-old Bennett, along with Nashannock teammates George Creamer and Ned Williamson, signed with the Detroit Aetnas.4 Though originally an amateur club, the Aetnas began dipping into the professional ranks in the summer of 1876, bringing an end to one of the strongest strictly amateur clubs Detroit had known.5

The next two seasons Bennett played for the Milwaukee Grays. The Grays were part of the League Alliance before joining the National League in 1878.

Bennett made his major-league debut on May 1, 1878, against the Cincinnati Reds at Avenue Grounds in Cincinnati. He went 2-for-4 and scored a run in the Grays’ 6-4 Opening Day loss. The next day the Reds best the Grays again as Bennett attempted to catch back-to-back games. However in the fourth inning, Bennett’s hands gave out and he moved to center field.6 Injuries hampered Bennett throughout the season.

The 23-year-old Bennett was still learning the position and was not the defensive standout he later became. On June 12 the Grays dropped a 1-0 10-inning decision to the Chicago White Stockings in a game during which Bennett made seven errors.7 After the game, Bennett was released. At the beginning of July, before the Grays series with Boston, “Bennett was re-engaged” and spent the rest of the season with the team.8

Bennett played in 49 games, 35 as a catcher, and batted.245 with one home run and 12 RBIs. The home run came on July 25 off 18-year-old rookie right-hander John Montgomery Ward in Milwaukee’s 7-1 win over the Providence Grays. The top of the ninth home run helped end Milwaukee’s 14-game losing streak that extended more than a month. Milwaukee finished the season in last place with a dismal 15-45 record and disbanded early in 1879.

In late February of 1879 Bennett and Bill Holbert, a fellow catcher who had most recently played with the Louisville Grays, attempted to organize a new professional club in Milwaukee. The pair set out to raise $1,000 in capital from investors but within two weeks the club fell through and the money was returned to the backers. Bennett dropped the attempt, concluding that the baseball business in Milwaukee was a thankless job: “If you ever catch me undertaking such a task again here, you can just lift my head from my shoulders and use it for a football.”9

With no prospects for baseball in Milwaukee, Bennett joined the Worcester Grays of the minor National Association, a team organized and managed by vagabond manager Frank Bancroft. With the additions of Bennett and backstop Doc Bushong, the Grays had two outstanding catchers. This was an asset during an era when catchers lacked the protective equipment and needed time to recuperate after catching a game. Bennett played in 42 games for Worcester and hit .328. Bushong played in 46 games and hit .290.

On June 2, 1879, Bennett played a key role in in the no-hit professional debut of left-hander Lee Richmond.10 The last-place Worcester club sent Richmond, a 22-year-old star pitcher on the Brown University team, to the mound to face the National League-leading Chicago White Stockings. The White Stockings were 14-1 at the time. Bennett played first base and went 1-for-2 with a triple, scored two runs, and made what was described as “a remarkably fine foul catch” in support of Richmond.11 The Grays shellacked the White Stockings, 11-0.

During the winter of 1879-80, Bancroft persuaded Bennett and some of his teammates to barnstorm through the Southern United States and Cuba. In late November the group, which included Bushong, George Wood, Lon Knight, Art Whitney, Chub Sullivan, Curry Foley, Arthur Irwin, and Tricky Nichols, made its way to Cuba. Calling themselves the Hop Bitters, the club became the first American professional team to visit Cuba.12 The trip was a flop, both financially and otherwise. Only a few games were played and the Americans dominated their Cuban hosts. Bennett and the Hop Bitters arrived back in New Orleans at the end of December and continued barnstorming.

In 1880 Worcester was admitted to the National League and became known as the Ruby Legs. That season, Bennett played in 51 games, 46 as a catcher, and hit .228 with 18 RBIs. The team finished in fifth place with a record of 40-43, its highest finish in its three years of existence. The Ruby Legs’ season included one notable highlight.

On June 12, 1880, Bennett’s name was etched into the annals of baseball history when he caught major-league baseball’s first perfect game. Richmond, who had tossed two National Association no-hitters in 1879, retired all 27 Cleveland Blues he faced in a 1-0 Ruby Legs victory at Worcester’s Agricultural Fair Grounds. Years later Richmond, who left baseball for a career in education, said that Bennett was his favorite catcher to work with and “the best backstop that ever lived.”13

While playing in Worcester, Bennett met Alice Spears, a young woman from Vermont. The couple married in 1882 and Alice would later play a key role in the development of the chest protector worn by catchers. According to Bennett, his wife was constantly worried about his safety as she watched him catch fastballs, block curves and fend off foul balls, all without the modern tools of ignorance. So the two set out to design something that would protect his rib cage and chest area. Bennett and his wife designed and made a “crude but very substantial shield … made by sewing strips of cork of a good thickness in between heavy bedticking material” that faintly resembled the modern catcher’s chest protector.14

Fearful of being taunted by spectators for wearing such a cowardly apparatus, Bennett wore the protective device under his jersey. After testing his new invention, Bennett wore the chest protector in a regular game, and with the eyes of thousands of spectators gazing upon him he would let a fast one hit him square on the chest, the ball would rebound back almost to the pitcher much to the amazement of the fans and players who weren’t onto the hidden cause.15

Years after his playing career ended, Bennett reflected on the evolution of the equipment and how it affected the position: “I remember the first gloves we had were padded across the palm, and the fingers were cut off at the second joint. Later on we used the big mitts, mask and breast protector, and catching became a cinch.”16 Indeed, mutilated hands, broken fingers, and cracked ribs were common injuries suffered by catchers during Bennett’s era.

At the end of the 1880 season, Bancroft was hired to manage the new National League franchise in Detroit and took several Worcester players with him, including Bennett, third baseman Art Whitney, and outfielders George Wood and Lon Knight.17 While the Wolverines finished above .500 only once in their first five years, the popular 26-year-old was entering his prime. He enjoyed the best years of his career in Detroit and soon became recognized as one of the game’s early stars.

In his first season with the Wolverines, Bennett established himself as one of the best players in the National League with a MVP-caliber season. He played in 76 games, 70 as the catcher, and hit .301 with a team-leading 7 home runs, 64 RBIs, and a .476 slugging percentage. His home-run and RBI totals were the second highest in the National League. Defensively he was even better, leading all catchers with 418 putouts and a range factor of 7.19. He also established a major-league record for catchers with a .962 fielding percentage. Bennett’s WAR rating for position players was 4.3, the second highest, as the Wolverines finished their inaugural season with a respectable record of 41-43.

According to baseball historian Peter Morris, Bennett took the first recorded “curtain call” in baseball on Opening Day of 1881. After hitting a home run off Buffalo’s Jack Lynch, Bennett was “loudly applauded, and the crowd would not desist until he bowed in acknowledgment.”18 While the home run had little impact on the outcome of the game, the Wolverines lost 6-5, the fans’ tribute to Bennett was a foreshadowing of the special relationship he would have with Detroit and its baseball fans.

Despite the team’s surprising fourth-place finish and Bennett’s immense popularity with Detroit fans, the Wolverines’ star catcher was quickly growing disenchanted. Bennett, who wanted to play for a winner, later said that he was unhappy playing for the Wolverines during the franchise’s early years. “During the next four years I wished many times I was out of Detroit, or rather out of that team,” he said. “It was awful.”19

Bennett continued to lead the Wolverines offense and enjoyed another fine season in 1882. In 84 games, 65 behind the plate, he again hit .301. He hit 10 triples and 5 home runs, drove in 51 runs, and had a .450 slugging percentage. Behind the plate, he led National League catchers in putouts (446) and range factor (7.94). Again, he was among the league leaders in WAR among position players (4.2) and helped the Wolverines finish above .500 for the first time.

Despite the team’s modest improvement, Bennett contemplated leaving the Wolverines at the end of the 1882 season.

Toward the end of the 1882 season, Bennett signed a preliminary agreement with the [Pittsburgh] Alleghenys of the American Association for his personal services for the next year. But then he had a change of heart, chose to stay in Detroit, and refused to sign the 1883 contract. The Alleghenys’ principal owner, Harmar Denny McKnight, sued, seeking a federal court injunction compelling Bennett to sign a formal contract and restraining him from playing for Detroit. The court dismissed the charge, deciding in Bennett’s favor that a preliminary arrangement did not amount to a final agreement; and, furthermore the contract that was presented for signature lacked mutually equitable terms between club ownership and the ballplayer.20

Perhaps Bennett’s change of heart was related to the realization that the grass might not have been greener on the other side of the fence. The Alleghenys finished the 1883 season in seventh place in the American Association with a record of 31-67. Regardless of the reason why, Bennett’s case was “baseball’s first real case of contract litigation.”21

The Wolverines were unable to build upon their first winning season and finished with a 40-58 record in 1883, dropping to seventh place. But it may have been Bennett’s best all-around season. He played in a career-high 92 games and established career highs in average (.305), hits (113), and OPS (.825). He hit five home runs, the sixth most in the National League, and drove in 55 runs. In 72 games behind the plate, he led National League catchers with 11 double plays and a .944 fielding percentage. His career-high WAR of 4.9 ranked third among all position players.

Bennett’s three-year performance between 1881 and 1883 (.302, 170 RBIs, .811 OPS) is impressive when one considers how grueling catching was in the early 1880s and the evolving nature of the game, which resulted in vast differences in players’ performance.

Bennett experienced an offensive falloff in 1884 as the Wolverines continued their downward spiral. He caught a career-high 80 games and appeared in 90 overall. He finished the year with a .264 average, 3 home runs and 40 RBIs. The Wolverines finished a dismal 28-84, 56 games behind the National League champion Providence Grays. Bennett recalled, “I thought sometimes we were lucky to finish last. Every week I caught a new pitcher.”22 The revolving door of Wolverines pitchers may have contributed to Bennett’s decline in fielding percentage and career-high passed balls.

After a decade-long absence from the game, bunting began to re-emerge in 1884, with Arthur Irwin and Cliff Carroll of Providence among the more adept practitioners of the art.23 Not everyone was pleased about the bunt’s return. Bennett was among those displeased. In a 1906 interview published in the Detroit News Tribune, Bennett said, “Bunting has destroyed baserunning. There is no necessity for a runner to take chances like they did before the bunt came into general use. As a result, one of the finer points of the great game has become almost a lost art.”24

Things hit rock bottom for the Wolverines at the start of the 1885 season. After opening with three straight wins against the Buffalo Bisons, Bennett and his teammates won only two of their next 28 and were buried deep in the National League cellar by the end of May. The team’s fortunes began to turn in June after they acquired Sam Thompson and eight other players from the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the Western League.25 From July 1, the team went 33-34 to finish the season in fourth place.

Bennett appeared in 91 games in 1885 and compiled a WAR of 4.5, the second highest of his career and fifth highest among position players, on the strength of his 42 extra-base hits and stellar defensive play. He finished the season with a .269 batting average, 5 home runs, and 60 RBIs.

In September of 1885, the Wolverines acquired the entire Buffalo roster when the Bisons disbanded. Among those acquired were Dan Brouthers, Hardy Richardson, Jack Rowe, and Deacon White. With a strong nucleus in place, Bennett was soon to realize his dream of playing on a winning team. The Wolverines’ record improved dramatically in 1886. The team finished with an 87-36 record, 46 wins more than the previous year and good enough for a second-place finish, 2½ games behind the first-place Chicago White Stockings.

Bennett’s offensive production dropped noticeably that year. However, he may have enjoyed the best defensive season of his career. In 72 games Bennett hit .243, his lowest average during his eight years with the Wolverines, with 4 home runs and 34 RBIs. Defensively, he played in 69 games behind the plate and compiled a defensive WAR rating of 2.0. He led all league catchers with a .955 fielding percentage and 13 double plays.

The 1887 season was the high point in the Wolverines’ history as they captured their first and only National League pennant with a record of 79-45. Bennett, however, was limited to only 46 games as the toll of catching for more than a decade began to take its toll. He finished the season with a .244 average with 3 home runs and 20 RBIs.

Bennett’s ability to play through pain was on full display during the Wolverines’ 1887 World Series against the American Association champion St. Louis Browns. Initially ruled out of the series by a doctor who feared he would be in danger of having his thumb amputated if he caught another game, Bennett was determined to play. Playing with “a pair of hands that could hardly grip the bludgeon,” Bennett performed admirably.26 In 42 at-bats, he hit .262, had two doubles, a triple, five stolen bases, and a team-leading 9 RBIs. Behind the plate, he held Arlie Latham and the other Browns basestealers in check as the Wolverines won the series 10 games to 5.

In 1888, the 33-year-old Bennett snapped back and enjoyed one of his better all-around seasons. In 74 games he hit .264 with 5 home runs and 29 RBIs. However, it was on defense that he shined brightest. Despite being the eighth oldest player in the National League, Bennett complied the highest defensive WAR rating of his career (2.2), as he broke his own single-season major-league record with a .966 fielding percentage. The Wolverines were unable to repeat the success they enjoyed the previous year, despite bringing back the most feared lineup in baseball. The team finished in fifth place with a 68-63 record.

With high salaries owed the team’s star-studded roster, gate receipts declining markedly, and debt mounting, the Wolverines folded in October 1888. On October 16, in an effort to recoup what cash they could, the club sold Bennett, Brouthers, Richardson, White, and Charlie Ganzel to the Boston Beaneaters for $26,000.27

Bennett was reported to have received a salary of $3,500 with the Beaneaters during the 1889 season, an enormous sum for that period, in part because of his ability to handle a pitching staff. During his five years with the Beaneaters, Bennett worked with legendary pitchers John Clarkson, Old Hoss Radbourn, and Kid Nichols. Bennett and Nichols were particularly close and remained friends for the remainder of their lives.

In his inaugural year in Boston, Bennett played in 82 games, all behind the plate, and hit a modest .231 with 4 home runs and 28 RBIs. He continued to pace National League catchers in fielding percentage with a .955 mark, 45 points higher than the league average for catchers and 18 points higher than Buck Ewing, who was considered the second-best defensive catcher of the era.

One thing that separated Bennett from most of his contemporaries was his ability to play through pain and injuries, especially to his hands. Jim Hart, the Beaneaters manager in 1889, said of Bennett’s ability to play through pain:

“He had more grit than any catcher I ever knew. A score of times when his hands were badly injured he would continue to catch, and the only way we would find out that he was hurt was to discover blood on the ball. I remember a game in Pittsburgh, the last one of the season in 1889 for the Boston club, when he refused to go out of the game until I simply refused to let him play any longer. Clarkson was pitching, and in the third inning he showed me the ball covered with blood. I called Bennett to the bench and asked to see his hands, and he refused to show them. Mike Kelly was playing right field, and I called him in to catch. Bennett wanted to catch the game out so much that he wouldn’t give Kelly the mask or the pad. I sent him home after the game, and two weeks later Bennett’s hands were so sore that he could hardly feed himself.”28

Another account of Bennett’s grit was cited by Peter Morris in his book Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero:

“Bennett declared that only a sissy would use a padded glove with the fingers and thumb cut off. During one of the games in which he figured a foul ball split the left thumb of Bennett’s hand from the tip right down to the palm. The flesh was laid open right to the bone. A doctor who examined it immediately told Bennett that it would be necessary for him to quit the game until such time as the thumb healed sufficiently. The physician pointed out … that blood poisoning might set in which would cause him the loss not only of the thumb but perhaps a hand or an arm. But despite all the doctor’s caution Bennett remained in the game catching day after day with his horribly mangled finger. He kept a bottle of antiseptic and a wad of cotton batting on the bench and between innings would devote his time to washing out the wound.”29

Despite Bennett’s decreased offensive production, the catcher remained in high demand after the 1889 season. After being offered a contract by the Boston Reds of the new Players’ League, Bennett was able to leverage the offer to sign a three-year contract to remain with the Beaneaters. The contract called for Bennett to receive a $6,000 signing bonus and a salary of $4,000 a year.30

News of Bennett’s shrewd deal with the Beaneaters was applauded by the Detroit Free Press, which praised him for his consistent work ethic and ability to handle pitchers:

“That Detroiters will rejoice in his good fortune goes without saying. No matter whether we had a tail end club or the world’s champions, there was no difference in the quality of his work. Young and nervous pitchers under his wise counsel and steady influence became valuable men. Detroit is more his house than any other place and it matters not how far away he goes, we shall always regard him as ‘our catcher.’”31

This was not a surprising commentary, given Bennett’s popularity in Detroit and the fact that he played with the Wolverines for all eight of the team’s seasons. He was one of only two players (the other was Ned Hanlon) to play for the Wolverines every season the franchise existed.

In 1890 Bennett played in 85 games and hit .214 with 3 home runs and 40 RBIs while leading all National League catchers in fielding for the third straight year with a .959 percentage. The Beaneaters, who were beaten out by the New York Giants by a single game in 1889, dropped to fifth place under first-year manager Frank Selee.

On August 12, Bennett hit a 12th-inning walk-off home run off Philadelphia left-hander Phenomenal Smith at Boston’s South End Grounds. The home run gave the Beaneaters a 1-0 victory. At the time, it was only the third time in National League history that a 1-0 game ended with a walk-off home run.32

Bennett’s 1891 season was nearly a carbon copy of the previous year, with one major exception. He hit .215 with 5 home runs and 39 RBIs, and for the fourth straight year led the league’s catchers with a .960 fielding percentage. The difference this season was that the Beaneaters finally won the National League championship. Boston finished 87-51, 3½ games ahead of the White Stockings.

By 1892 the wear and tear of catching had taken a tremendous physical toll on Bennett. King Kelly, who took over as the team’s number-one backstop that season, later commented on the effect catching had on Bennett’s hands. Kelly said, “If I had hands such as Charlie Bennett, I wouldn’t catch a game of ball for a whole church full of millionaires with their entire wealth stuffed in their pockets.”33 As a backup, Bennett played in only 35 games and hit .202 (13 points higher than Kelly) with one home run and 16 RBIs. The Beaneaters won 102 games on the way to their second consecutive pennant.

The 1892 season had a unique split-season arrangement, with Boston winning the first half and Cleveland the second. In the championship series against the Cleveland Spiders, Bennett went 2-for-7 with one RBI as the Beaneaters took the series, five games to none.34

Bennett shared the team’s catching duties with Ganzel and Bill Merritt in 1893, appearing in 60 games behind the plate. Still one of the better defensive catchers, the 38-year-old veteran of 15 major-league seasons hit only .209 with 4 home runs and 27 RBIs as the Beaneaters rolled to their third consecutive title.

Bennett’s baseball career came to a tragic end on January 10, 1894. He was on his way to a hunting trip with former Beaneaters teammate John Clarkson when his legs were crushed by a passenger train at a stop near Ottawa, Kansas. The accident occurred when Bennett stepped off the train to talk with an old friend who lived in the area. When the two friends said goodbye and the train started moving, Bennett turned to catch the railing of the train, but his foot slipped and went over the rail. Bennett pushed his right leg against the rail to push himself back, but it also slipped and went over the track.35 The train’s wheels ran over his left foot and right leg at the knee.

That evening, doctors at the North Ottawa Hospital amputated the 39-year-old Bennett’s left foot just above the ankle and his right leg just above the knee.36 Bennett’s nephew, George Porter, whom he was particularly close to, recounted the tragic tale in a 1934 Detroit Free Press interview:

“Five doctors worked on him. It was the blackest day of my life. His physical condition was so good that ten days later they were able to move him the 18 miles through zero degree weather to our home where we nursed him back to health.”37

Amazingly, just three months after the accident, Bennett had regained much of his strength and began the process of learning to walk with prosthetic legs.

After a few months of convalescing, Bennett and his wife returned to Detroit and, along with a partner, opened a cigar store on Woodward Avenue. According to the Detroit Free Press, after his intentions were announced publicly, “Charlie received over 100 letters from a friend asking if the report be true. One lady wrote to Mrs. Bennett: If Charlie Bennett opens a cigar store in Detroit, all the ladies will commence smoking.”38 For some time the cigar store was profitable, but increased competition from large tobacco manufacturers eventually forced him to sell the business.

The loss of Bennett was a shock to Boston fans and provided a terrible blow to the psyche of the Beaneaters. Following three consecutive National League pennants, they finished the 1894 season in third place with a record of 83-49, eight games behind the pennant-winning Baltimore Orioles and five behind the second-place New York Giants. According to some newspaper accounts, the absence of Bennett was one of the reasons given for the team failing to win a fourth consecutive pennant.39

On August 26, 1894, the team held a benefit to help Bennett pay his medical bills. At one point bowed to the crowd and stood speechless and legless at home plate. The benefit was attended by the heavyweight boxing champion, Gentleman Jim Corbett, who briefly played in the contest. A crowd of 9,000 fans attended and Bennett was given the $6,000 gate.40

Never one to complain, Bennett handled his fate in the most optimistic and dignified manner possible. After all, he was fortunate to have survived such a horrible accident. He continued to hunt (from his buggy) and fish. In fact, he was doing so well getting around that during his visit to Boston for a benefit game the Beaneaters were hosting, former teammate and fellow catcher Charlie Ganzel proposed a race between the two. Bennett, known for his good sense of humor, said he was willing if he could have a 98⅓-yard head start.41

On April 28, 1896, the Detroit Tigers of the Western League opened their new ballpark, named Bennett Park in tribute to Bennett. A cannon brought from nearby Fort Wayne was fired to signal the start of the season and Bennett himself caught the ceremonial first pitch from Wayne County treasurer Alex McLeod.42 Bennett caught the ceremonial first pitch for every Tigers home opener through 1926.43

In later years Bennett took up the hobby of painting china dishes. It was hard with his mangled fingers from catching, but “the perseverance that made him the greatest catcher base ball ever saw made it possible to master the art.”44 The former catcher’s intricate creations eventually commanded “a ready market and good price.”45

Bennett’s 15-year major-league career ended with modest offensive numbers: a .256 batting average, 55 home runs, and 533 RBIs. During his eight-year stint in Detroit, Bennett hit .278 with 37 home runs and 353 RBIs. It wasn’t until the long-term effects of catching with limited protection hampered his ability to grip the bat that his offensive numbers began to decline. Still, it was Bennett’s defensive prowess that differentiated him from his catching peers.

When Bennett began his major-league career, the National League record for games caught in a season stood at 63. He eclipsed that mark in 10 different seasons. Altogether he played in 1,062 games, 954 as a catcher, which at the time of his accident was a major-league record that stood until 1897. He led in fielding percentage seven times and retired with a fielding percentage of .942, a major-league record for catchers that stood until 1896. His career total of 114 double plays and 5,123 putouts also stood as major-league records until 1900 and 1901, respectively. In 1983 Bennett was recognized by SABR’s Nineteenth Century Committee as the best nineteenth-century catcher not in the Hall of Fame.46 In 2021, he was honored again as SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Legend of the year.

Bennett’s health began to deteriorate in early 1926 and in November he underwent surgery to remove a “superorbital abscess of the face.”47 He never fully recovered from the surgery. He died at his home in Detroit on February 24, 1927. Bennett was 72 years old. He was survived by his wife, Alice, who died in 1931. The couple had no children but always considered his nephew George and George’s wife, Sarah, as their own children. He was buried at Woodmere Cemetery in Detroit.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Richard Bak, “The Bittersweet Story behind Charlie Bennett’s Park.” Retrieved from https://detroitathletic.com/blog/2012/09/03/the-bittersweet-story-behind-charlie-bennetts-park/.

2 “The Boys Who Catch: Pen and Ink Portraits of the Receivers of the Country,” The Sporting News, November 10, 1888: 5.

3 George R. Pulford, “Winter Journeys to the Homes of Celebrated Ball Players – Peerless Charlie Bennett,” Seattle Star, January 4, 1908: 2.

4 George Creamer was a light-hitting (.215) second baseman who played seven seasons (1878-1884) for the Milwaukee, Syracuse, and Worcester teams in the National League and the Alleghenys of Pittsburgh in the American Association. Ned Williamson had a 13-year major-league career, including 11 seasons with the National League’s Chicago White Stockings. The stocky third baseman and shortstop established the single-season major-league record of 27 home runs. The record stood until 1919 when Babe Ruth hit 29.

5 “Record of the Aetnas: The Four Years’ Career of the Club was a Brilliant One,” Detroit Free Press, February 24, 1889: 7.

6 Dennis Pajot, The Rise of Milwaukee Baseball: The Cream City from Midwestern Outpost to the Major Leagues, 1850-1901 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2009), 62.

7 Pajot, 66.

8 Ibid.

9 Evening Wisconsin (Milwaukee), as cited by Pajot, 70.

10 Left fielder Abner Dalrymple was the only Chicago batter to reach base, on a first-inning leadoff walk. Richmond pitched a second no-hitter later that year.

11 John R. Husman, “Lee Richmond’s No-Hit Debut,” in Bill Felber, ed., Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2013), 114.

12 Brian McKenna, “Doc Bushong,” SABR BioProject. Retrieved from https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/5d4b5fe8.

13 E. Bates, “Improved Game: J. Lee Richmond, Once a Great Pitcher, Is One of the Few Veterans Who Concedes Advance Base Ball,” Sporting Life, March 19, 1910: 12.

14 Maclean Kennedy, “Charlie Bennett, Former Detroit Catcher, Inventor of Chest Pad: Old-Time Star and Mrs. Bennett Made First One Out of Cork Sewed Between Bed-Ticking Strips,” Detroit Free Press, August 2, 1914: 19.

15 Ibid.

16 Pulford.

17 John R. Husman, “Roger Connor’s Grand Slam,” in Inventing Baseball, 133.

18 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 414.

19 “Poor Charley Bennett: The Afflicted Catcher Recites His Baseball Career,” Detroit Free Press, June 23, 1894: 4.

20 James K. Flack, “Becoming a Contract Jumper: Deacon Jim McGuire’s 1902 Decision,” Baseball Research Journal, (Phoenix: SABR, Fall 2018): 113.

21 Patrick K. Thornton, Legal Decisions, 33; Allegheny Base Ball Club v. Bennett, 14 F.257 (W.D. Pa., 1882), https://law.resource.org/pub/us/case/reporter/F/0014/0014.f.0257.pdf, cited by Flack.

22 “Poor Charley Bennett: The Afflicted Catcher Recites His Baseball Career.”

23 Morris, 55.

24 “Stories of Early Base Ball Days Told by Charlie Bennett, King of the Olden Catchers,” Detroit News Tribune, March 11, 1906, cited in Morris, A Game of Inches, 56.

25 On June 15, 1885, the Wolverines acquired Thompson, Chub Collins, Jim Donnelly, Jim Keenan, Larry McKeon, Gene Moriarty, Dan Casey, Sam Crane, and Deacon McGuire from the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the Western League for $4,000 (only $2,000 was paid due to dispute).

26 “C.W. Bennett, Veteran Baseball Star Dies,” Detroit Free Press, February 25, 1927: 2.

27 Ibid.

28 “Charlie Bennett: ‘Our Catcher,’” Retrieved from Bless You Boys, https://blessyouboys.com/2018/3/8/17097104/charlie-bennett-our-catcher.

29 Peter Morris, Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), 208-209.

30 “Sporting Matters: Some Facts in Relation to Bennett’s League Contract Signature,” Detroit Free Press, February 16, 1890: 6.

31 Ibid.

32 Lyle Spatz, ed., The SABR Baseball List & Record Book (New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 55.

33 “Charlie Bennett: ‘Our Catcher.’”

34 The series lasted six games with one game ending in a tie. Officially, the Beaneaters beat the Spiders 5-0-1.

35 “Poor Charley Bennett: The Afflicted Catcher Recites His Baseball Career.”

36 “A Tragic Close to a Brilliant and Long Career on the Diamond: Details of the Horrible Accident Which Cut Off Bennett’s Legs and Livelihood – A Tribute to the Suffering Player – Sketch of His Career,” Sporting Life, January 20, 1894: 3.

37 “Old Catcher Was Iron Man: Train Mishap Ended Bennett’s Career,” Detroit Free Press, September 30, 1934: 30.

38 “Charlie Bennett: ‘Our Catcher.’”

39 Ibid.

40 “Nearly $6000: Benefit to Bennett Was a Grand Success; Catcher Bowed to 9000 Friends; Walked Out to Home Plate to Do It; Champion Corbett in the Left Field,” Boston Globe, August 28, 1894: 1.

41 “Charlie Bennett in Town,” Boston Post, August 26, 1894: 3.

42 Bak.

43 Jeffrey M. Samoray, “Tigers Celebrate Centennial at Same Site,” Detroit News, April 28, 1996: 5E.

44 Pulford.

45 Ibid.

46 J.R. Husman, “Charles Wesley Bennett,” in R.L. Tiemann and M. Rucker, eds., Nineteenth Century Stars (Manhattan, Kansas: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989).

47 “C.W. Bennett, Veteran Baseball Star Dies,” Detroit Free Press, February 25, 1927: 1. An orbital abscess is an inflammation of eye tissues behind the orbital septum. It is most commonly caused by an acute spread of infection into the eye socket from either the adjacent sinuses or through the blood.

Full Name

Charles Wesley Bennett

Born

November 21, 1854 at New Castle, PA (USA)

Died

February 24, 1927 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.