July 28, 1884: Old Hoss Radbourn: 59 or 60 victories?

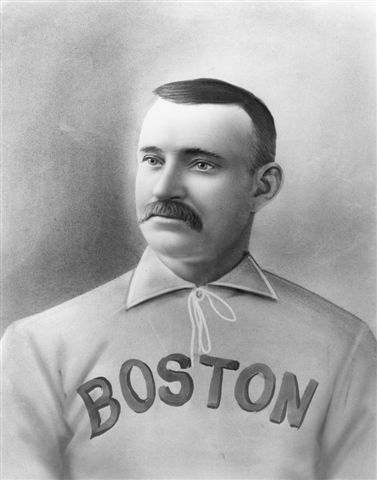

Two remarkable pitchers powered Providence’s drive toward the 1884 National League pennant. In late June the Grays stood first at 33–10, thanks in large measure to the work of 21-year-old Charles Sweeney and veteran Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, who was eight tough years older. Sweeney won 15 of his 21 starts, including his sensational 19-strikeout performance on June 7 against Boston, while Radbourn won 18 of his 22 games.

Two remarkable pitchers powered Providence’s drive toward the 1884 National League pennant. In late June the Grays stood first at 33–10, thanks in large measure to the work of 21-year-old Charles Sweeney and veteran Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, who was eight tough years older. Sweeney won 15 of his 21 starts, including his sensational 19-strikeout performance on June 7 against Boston, while Radbourn won 18 of his 22 games.

Trouble, however, lay ahead. Sweeney’s brilliant performance against Boston fueled his alcohol-laced ego, while Radbourn grew sulky about losing his role as the Grays’ dominant starter. In mid-July the Grays felt compelled to suspend the Hoss for all-around cussedness, including open contempt for his teammates (he had begun dressing in the visitors’ locker room) and ostentatiously blowing his stack during one game, endangering catcher Barney Gilligan.1

After Radbourn had fumed on the sidelines for a week, a new crisis erupted. On July 22 Sweeney, incensed at the orders of Grays manager Frank Bancroft to leave the pitcher’s box during the game he had started and trade places with the right fielder, instead stormed off the field and declared his intent to quit the team. The Grays directors expelled him and then came exceedingly close to folding the club, having no real pitchers left. Old Hoss, after all, wanted to leave Providence, and had little interest in pitching any more for the Grays. But National League President A.G. Mills begged Providence to stay afloat, and the Grays decided to go forward, as manager Bancroft coaxed, or perhaps bribed, the moody Radbourn to rise above his bitterness and return.2 The reinstated Radbourn won his 25th game on July 23, and his 26th on July 26, and Providence was back, breathing down Boston’s neck.

On Monday the 28th, at Philadelphia’s Recreation Park, located along Ridge and Columbia (now Cecil B. Moore) avenues, Radbourn got a well-deserved break from pitching. Cyclone Miller, whom the Grays had stolen from the outlaw Union Association, got the start, and “showed up strong,” surrendering only one hit in the first four innings. But in the fifth Miller lost his edge, as he tended to do in later innings. The mediocre Phillies bunched three singles, along with a base on balls, and by the time the carnage was over, Providence trailed 4–3.3

After Providence stormed back with four runs in the sixth to go ahead 7–4, manager Bancroft decided to play it safe by ordering the erratic Miller to trade places with Radbourn, who to that point had been stationed out in right field. Radbourn proved untouchable for the next four innings, allowing no hits as the Grays coasted to an 11–4 win, taking over first place in the National League.4 The Grays would go on to win the pennant easily with Radbourn pitching almost every game.

The July 28 game was hardly a great one, and no one would pay the slightest attention to it all these years later, if not for one thing: It set off a fiery debate among baseball aficionados about whether Radbourn really won 60 games during his immortal 1884 season, or only 59. We have the late Frederick Ivor-Campbell, a brilliant baseball scholar and Radbourn expert, to thank for the controversy.

The editors who compiled the epochal first edition of Macmillan’s Baseball Encyclopedia (1969) knew that creating a standardized and official collection of baseball numbers would be a difficult task because rules for statistics had changed dramatically over the years. The concept of pitching wins, for instance, did not even exist during Radbourn’s immortal season of 1884; fans just looked at the records of the teams themselves, forming a general impression of which pitcher was doing the best work. To draw early baseball into the grand sweep of the record book, a Special Baseball Records Committee had to be created. “Most of the important issues concerned the period before 1920, a time that was somewhat chaotic in baseball for record-keeping procedures,” the Encyclopedia editors noted, in a grand understatement.5 The committee resolved to count pitching wins and losses prior to 1920 by using the 1950 rule, which had established inflexible guidelines for defining wins and losses, sparing scorers the judgment calls they had been making.6

Using the 1950 rule, the Encyclopedia gave Radbourn the grand total of 60 wins, the all-time record for a single season, and one of baseball’s golden numbers. Since Radbourn finished all 73 of the games he started that year, most wins and losses are beyond dispute. But Ivor-Campbell, delving into the July 28 game, discovered that the Encyclopedia had erred in assigning Radbourn a victory that day, meaning he should have been given only 59 wins.7 According to the 1950 rule, if a starter pitches five full innings (as Miller did), and if a reliever comes in with his team ahead and preserves the victory, the starter gets the win, not the reliever.8 It did not matter that Radbourn pitched nearly half the game — and pitched markedly better than Miller.

Though the Encyclopedia kept claiming Old Hoss had won 60, other sources, such as Total Baseball (1989), came to accept the less exalted 59 as the official total. In 2019, SABR researcher Frank Williams dug into the case again and determined that, by the standards of the day, Radbourn should be credited with 60 wins, since he was the most effective pitcher in that July 28 game. Baseball-Reference.com now lists Radbourn with 60 wins as a result. But, as Ivor-Campbell well knew, some of this was like the efforts of medieval clerics to estimate how many angels could dance on the head of a pin. Any number is inclined to be a modern extrapolation and interpretation, since the statistic of pitching wins simply did not exist in Radbourn’s day.

Whichever win total we use, it is undeniable that Radbourn’s performance in 1884 was one of the greatest, grittiest performances in baseball’s long history — something recognized in his time and well over a century later.

An earlier version of this article was published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 Radbourn blew up in the July 16 game against Boston. See Providence Journal, July 17, 1884. Dressing-room detail from Providence Evening Telegram, July 17, 1884.

2 Recounted in my book Fifty-nine in ’84: Old Hoss Radbourn, Barehanded Baseball and the Greatest Season a Pitcher Ever Had (New York: HarperCollins, 2010), p. 204-7.

3 Sporting Life, Aug. 6, 1884.

4 Ibid.

5 The Baseball Encyclopedia (Toronto: Maxwell Macmillan Canada, 1969), p. 2,327.

6 Ibid, p. 2328, decision No. 12.

7 Ivor-Campbell describes his discovery in an April 20, 1991, article, “How Many Wins for Radbourne in 1884 – 59, 60 or 61?” which he provided to me in manuscript form.

8 The Baseball Encyclopedia, Appendix C, p. 2,335.

Additional Stats

Providence Grays 11

Philadelphia Phillies 4

Recreation Park

Philadelphia, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.