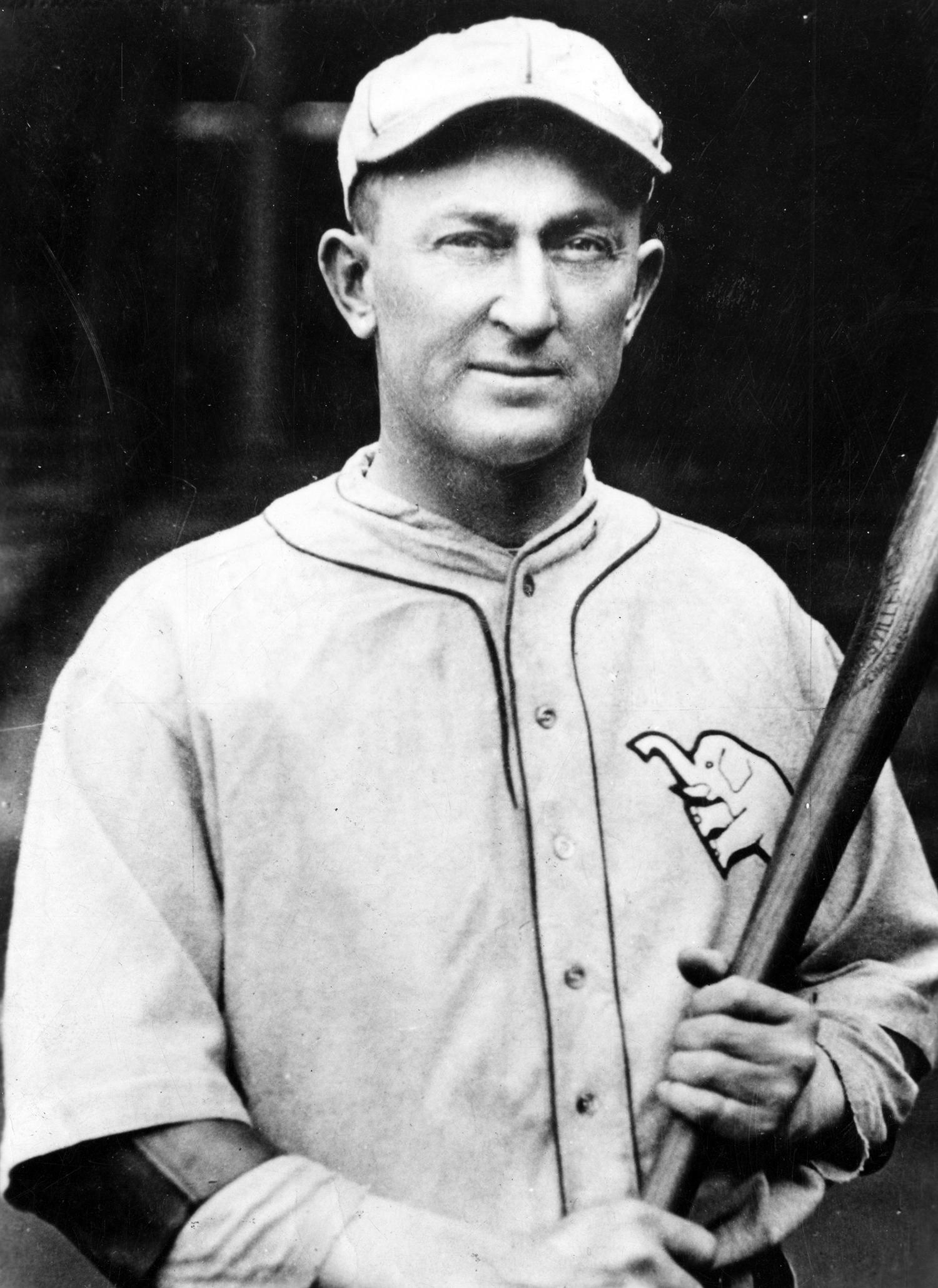

May 10, 1927: Ty Cobb returns home to Detroit with Philadelphia A’s

Forty thousand fans turned out at Navin Field on a cloudy and chilly Tuesday afternoon to witness an extraordinary homecoming: Ty Cobb, the greatest Tiger of them all, was returning to Detroit – in the uniform of the visiting team.

Forty thousand fans turned out at Navin Field on a cloudy and chilly Tuesday afternoon to witness an extraordinary homecoming: Ty Cobb, the greatest Tiger of them all, was returning to Detroit – in the uniform of the visiting team.

The Tigers had fallen from fourth to sixth place in 1926, and to many it may have seemed as if age were finally catching up with the mighty Ty Cobb. Cobb had recovered from eye surgery in March to hit .339, but had played in only 79 games. It was no secret that his managerial style didn’t always sit well with his players and that he was often at odds with club ownerFrank Navin. Still, it took the baseball world by surprise when Cobb announced on November 3 that he was retiring from the game.

Sportswriters and editorial columnists were still rhapsodizing about Cobb’s illustrious career when on November 29 the Cleveland Indians’ celebrated player-manager, Tris Speaker, announced that he also was retiring. At 38, Speaker was still a productive player, and had just managed the Indians to a second-place finish, three games behind the New York Yankees. “I am taking a vacation from baseball,” Speaker said, “that I suspect will last for the remainder of my life.”1

A few weeks later the reason for the sudden retirement of two of the game’s biggest stars became apparent. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis made public the shocking claim of Dutch Leonard, a former Tigers pitcher: Leonard, along with Cobb, Speaker, and Cleveland outfielder JoeWood, had conspired to fix a game between Detroit and Cleveland on September 25, 1919.

The most suggestive evidence came in the form of two letters, one from Wood and one from Cobb, written to Leonard in the fall of 1919 alluding to wagers. In a hearing before Landis, Cobb and Wood admitted to having written the letters, but the gambling references, they claimed, involved horse racing. Leonard’s accusations, Cobb contended, were in retaliation for his having waived Leonard to the Pacific Coast League back in 1925. Speaker denied any wrongdoing, but under considerable pressure from American League President Ban Johnson, Cobb and Speaker agreed to retire.

The alleged fix became major news across America. Newspapers were filled with stories and speculation. A few sports columnists castigated Cobb and Speaker, but many, many more attacked Leonard for sullying the good names of two of baseball’s most lionized figures. Humorist Will Rogers put it for like-minded baseball fans across the country in a piece he wrote for the New York Times: “If they’d been selling out all these years I would have liked to have seen them play when they wasn’t selling.”2

Cobb professed his innocence in no uncertain terms. “I have been in baseball for 22 years. I have played the game as hard and square and clean as any man ever did. All I thought of was to win. My conscience is clear.”3

When Leonard refused to travel to Chicago in January to face Cobb and Speaker at another hearing, Landis, having no good evidence upon which to ban the two stars, and undoubtedly feeling the pressure of a decidedly pro-player public and press, ruled that the pair had been officially cleared, stating, “These players have not been, nor are they now, found guilty of fixing a ball game. By no decent system of justice could such finding be made.”4

Landis reinstated Cobb and Speaker to their former clubs, but the Tigers and Indians, in turn, chose to give each his unconditional release. Speaker signed with the Washington Senators. Cobb accepted an offer from Philadelphia Athletics owner and manager Connie Mack for a salary reported at $40,000, with a $25,000 signing bonus and $10,000 in other bonuses,5 making Cobb, at $75,000, the highest paid player in baseball.6 Cobb was quoted as saying he returned only to seek vindication, and so that he could say he left baseball on his own terms.7

If it was vindication he was seeking, Cobb was surely finding it in Philadelphia: A month into the season he was hitting a robust .408, the second highest average in the league, and was averaging better than one run scored per game. He had hit safely in 10 straight games coming into the series with Detroit.

An on-field dust-up in Philadelphia involving Cobb, teammate Al Simmons, and members of the Boston Red Sox had moved Ban Johnson to fine and suspend Cobb and Simmons on May 6. Public outcry, however, and pressure from highly placed individuals planning for Cobb’s homecoming, persuaded Johnson to lift the ban on the morning the Athletics arrived in Detroit.

And so it was that a delegation of dignitaries led by Detroit Mayor John W. Smith was there to greet Cobb and the Athletics as they stepped off a steamer from Cleveland on the morning of May 10. A testimonial luncheon honoring Cobb was held at noon, followed by a parade to the ballpark headed by a police motorcycle escort and a military band.

In pregame ceremonies broadcast by a local radio station, Cobb was presented with an assortment of gifts including a giant floral horseshoe, a silver serving set, and a new automobile. A handful of speeches from dignitaries and a few words of appreciation from Cobb were boomed to the crowd through a microphone placed at home plate. As the players warmed up, Cobb clinched his warm welcome when, after catching a fly ball, he tossed it over the screen into the bleachers in right field.

Cobb, batting third in the lineup, stepped into the batter’s box in the first inning to a lusty roar from the crowd. He responded by driving a pitch from Earl Whitehill down the right-field line for a double, moving Eddie Collins, who had walked to lead off the game, to third. Collins and Cobb then scored on a single to center by Simmons, giving the Athletics a 2-0 lead. The game had to be held up for several minutes in the bottom half of the inning as Cobb walked back and forth in front of the bleachers, signing autographs and soaking up applause.

In the third inning Cobb drew a base on balls but advanced no further than second; in the fourth he struck out to retire the side. In the field, Cobb thrilled the crowd with two catches that were “distinctly spectacular,”8 once going into the overflow crowd to pull down a high fly off the bat of Jack Warner and again in snaring a liner off the bat of Lu Blue while running at top speed diagonally across the field.

In the seventh inning Cobb drove the ball hard between short and third, but Tigers shortstop Jackie Tavener got a glove on it and threw out Bill Lamar, who was steaming toward third. Cobb, safe at first, was removed from the game to thunderous applause. WalterFrench came in to run for Cobb and afterward replaced him in right field.

Lefty Grove had the game well in hand for Philadelphia most of the afternoon, surrendering one run in the third inning and little else as the Athletics breezed to a 3-1 lead. Whitehill had recovered after the first inning, being touched for only one more run until he was removed for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the eighth. Philadelphia roughed up reliever Rip Collins for three runs on four hits, so that it mattered little that Grove struggled a bit in the bottom of the ninth. The Tigers, entering the inning with a five-run deficit, bunched two hits, an error, and a walk for two more runs before Grove regrouped and retired the last three batters to seal a 6-3 victory for the Athletics.

“I’m glad to be back here, even if I do appear with the visiting team,” Cobb told the assembled press corps. “I will always have a soft spot for Detroit fandom and my many fine friends here who have done so much for me.”9

This article appeared in “Tigers By The Tale: Great Games at Michigan and Trumbull” (SABR, 2016), edited by Scott Ferkovich. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com were also accessed.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/DET/DET192705100.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1927/B05100DET1927.htm

Books

Alexander, Charles C., Ty Cobb (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Holmes, Dan, Ty Cobb: A Biography (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2004).

Rhodes, Don, Ty Cobb: Safe at Home (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2008).

Newspapers

Detroit Free Press.

Detroit Tribune.

Philadelphia Inquirer.

Websites

Baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Henry P. Edwards, “Happy Jack Best Bet to Follow Speaker as Next Indian Pilot,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 30, 1926, 1.

2 Will Rogers, “Will Rogers’ Christmas Advice and a Tribute to Ty and Tris,” New York Times, December 24, 1926, 12.

3 “Baseball Scandal Up Again, With Cobb and Speaker Named,” New York Times, December 22, 1926, 17.

4 “Cobb and Speaker Cleared by Landis in Baseball Probe,” New York Evening Post, January 27, 1927, 1.

5 “Athletics Get Cobb for $75,000 for Year,” New York Times, February 9, 1927, 14.

6 Ibid.

7 Ty Cobb and Al Stump, My Life in Baseball: The True Record, (New York: Doubleday, 1961), 248.

8 Sam Greene, “Cobb Is Still Cobb, Detroiters Agree,” The Sporting News, May 19, 1927, 1.

9 William M. Anderson, The Glory Years of the Tigers: 1920-1950 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2012), 71.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia A’s 6

Detroit Tigers 3

Navin Field

Detroit, MI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.