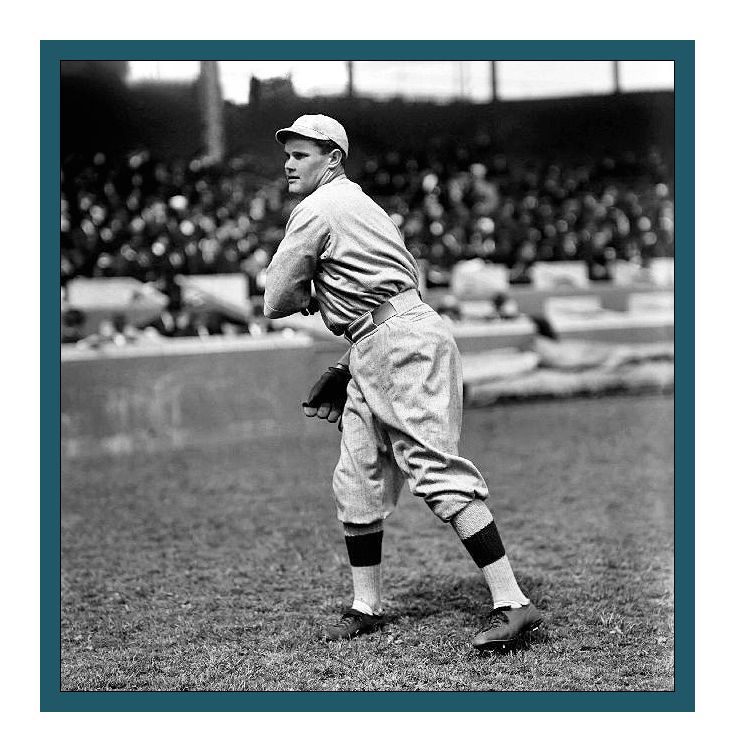

Dutch Leonard

A hard-throwing, spectacularly talented left-hander who posted the best single-season earned run average in American League history in 1914, Dutch Leonard was also one of the Deadball Era’s most controversial figures. At nearly every stop along his journey in professional baseball, Leonard feuded with management over his salary, and at one point was even suspended from organized baseball for nearly three years for refusing to report for work.

A hard-throwing, spectacularly talented left-hander who posted the best single-season earned run average in American League history in 1914, Dutch Leonard was also one of the Deadball Era’s most controversial figures. At nearly every stop along his journey in professional baseball, Leonard feuded with management over his salary, and at one point was even suspended from organized baseball for nearly three years for refusing to report for work.

Regarded as a selfish, cowardly player by many of his contemporaries, Leonard frittered away much of his major league career, alternating periods of brilliance with long bouts of inertia. “As a pitcher, he was gutless,” Hall of Fame umpire Billy Evans once declared. “We umpires had no respect for Leonard, for he whined on every pitch called against him.” After exiting the game in 1925, Leonard touched off one of the biggest scandals in baseball history when he accused Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker of conspiring to throw a baseball game in 1919. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis dismissed the charges, and Leonard retired to his California ranch, where he earned millions of dollars growing grapes.

Hubert Benjamin Leonard was born on April 16, 1892, in Birmingham, Ohio, the youngest of six surviving children of David and Ella Hershey Leonard. For a time David worked as a real estate agent in Toledo, before moving the family to California in the early 1900s and finding work as a carpenter. While Hubert’s older siblings became accomplished musicians (a brother, Cuyler, eventually made a name for himself as a composer and trumpet soloist), Hubert gravitated toward the pitching mound. In 1911, “Dutch” (a moniker hung on him during his childhood because he “looked like a Dutchman”) pitched for the highly regarded St. Mary’s College team while attending classes there.

He was spotted by a scout for the Philadelphia Athletics, who signed him during the 1911 campaign. With the Athletics rotation already loaded with the likes of Jack Coombs, Eddie Plank, Chief Bender and Cy Morgan, Leonard never appeared in any games. The following year, Leonard joined the Boston Red Sox for spring training, but developed a lame arm and failed to make the team. Sent to Worcester of the New England League, Leonard was bombed in one of his first outings and shortly thereafter abandoned the club. He showed up at Boston team headquarters and complained to club president Jimmy McAleer that “I didn’t get any support. It’s a rotten league. I won’t play there any more.” Still sensing promise in the young left-hander’s arm, Boston sent Leonard to Denver of the Western League, where he overcame a midseason suspension for insubordination to win 22 games and strike out 326 batters in 241 innings of work. The following spring Leonard made the Red Sox squad out of spring training and joined the rotation.

Darkly-complexioned and built “more like a football player than a baseball player” according to F.C. Lane, the stocky 5’10 ½” Leonard relied on the classic combination of an overpowering fastball and sharp-breaking curve. Later in his career he mixed in the spitball, and in 1920 became one of the “grandfathered” pitchers allowed to continue throwing the pitch after it was made illegal. In his rookie season with the 1913 Red Sox, Leonard posted a 14-17 record and 2.39 ERA in 259 1/3 innings of work. His biggest problem was his control: for the season he struck out 144 batters but also walked 94. All in all, it was a solid performance by the 21-year-old southpaw, but it gave little indication of the dominance he would achieve the following year.

Leonard’s historic 1914 campaign was cut short by a wrist injury in early September, but in the 36 games in which he pitched, including 11 in relief, the left-hander posted an astounding 0.96 ERA, still the lowest mark in the twentieth century and the second best all-time, behind Tim Keefe’s 0.86 recorded for the 1880 Troy Haymakers of the National League. (Keefe’s record was established in just 105 innings, good enough to qualify for the record only because his team played just 83 games that season.) Leonard pitched 224 2/3 innings in his record-setting summer, striking out 176 (giving him a league-best strikeout rate of 7.05 per nine innings) and lowering his walk total to 60 while hitting eight batters. For the season, he allowed just 24 earned runs (10 unearned) and won 19 games against five defeats.

He didn’t win his first game of the season until his fourth start, a 9-1 victory on May 4 against Philadelphia. After dropping a game to Washington on May 30 to run his record to 5-3, Leonard did not lose another game until August 13, running off a 12-game winning streak during which he struck out 92 batters in 118 innings. Despite his microscopic ERA, Leonard did not enjoy any long scoreless inning streaks or periods of noteworthy invincibility. Rather, he remained thoroughly consistent throughout the season, shutting out his opponents in seven of his starts and allowing just one run in 10 other starts. He surrendered more than two runs in a game just four times all season, and never allowed more than four runs in any start.

Because Leonard’s season was curtailed by injury, the pitcher failed to reach many of the milestones that were most noted at the time. He failed to win 20 games, and except for ERA (which had only been an official American League statistic since the previous season) did not lead the league in any major pitching category. For this reason, Leonard’s 1914 performance went largely unheralded in the press. Even Leonard regarded his work that year as incomplete. As he later told F.C. Lane, “If I hadn’t broken my wrist I think I would have done very well that year.”

Nonetheless, Leonard’s 1914 season did raise expectations for the 1915 campaign, which would prove to be a resounding success for the Boston franchise but a turbulent year for its ace southpaw. After receiving a raise in salary to $5,000 per year, Leonard reported to the team out of shape, and started only three games in the first six weeks of the season. In late May, Leonard was suspended by the club for insubordination. According to newspaper reports, Leonard accused club owner Joseph Lannin of undermining manager Bill Carrigan’s authority and generally mistreating his players. Leonard did not return to the starting rotation until early July, though he finished the season strong, posting a 15-7 record and 2.36 ERA. For the second consecutive year, Leonard led the American League in strikeouts per nine innings pitched, with 116 strikeouts in 183⅓ innings. He rounded out his season in impressive fashion, beating Philadelphia’s Pete Alexander in Game Three of the World Series, 2-1. The Red Sox prevailed in the Series over the Phillies in five games.

Leonard proved more durable over the next two seasons for the Red Sox, throwing a combined 568⅔ innings in 1916 and 1917, and winning 34 games against 29 defeats. Although his strikeout rate continued to fall and he was no longer considered one of the game’s overpowering pitchers, Leonard did pitch his first no-hitter in 1916, a 4-0 shutout over the St. Louis Browns on August 30. That autumn, Leonard also won his second and final World Series start, pitching Boston to a 6-2 victory over Brooklyn in Game Four, helping the Red Sox win another Series, in six games.

In 1918, Leonard pitched a second no-hitter, a 5-0 shutout victory, this time over the Detroit Tigers on June 3. His season came to an end a few weeks later when he circumvented the draft by joining the Fore River (MA) Shipyard team, for whom he won three games.

Prior to the 1919 season Leonard was included in the trade which also sent Ernie Shore and Duffy Lewis to the New York Yankees. Unlike Shore and Lewis, however, Leonard never appeared in a Yankee uniform and became a salary holdout. According to one report, Leonard demanded that his entire 1919 salary be deposited into a savings account, a request which infuriated New York owner Jacob Ruppert. “No man who doesn’t trust my word can pitch for my team,” Ruppert declared. In late May, the rights to the still-unsigned Leonard were sold to the Detroit Tigers for $12,000.

Now relying more on the spitball, Leonard spent the next three seasons with the Tigers, posting a modest 35-43 record. Prior to the 1922 season, Leonard again became tangled in a salary dispute, this time with Detroit owner Frank Navin, who refused to meet the pitcher’s demands. Leonard in turn violated the reserve clause in his contract by jumping to Fresno of the independent San Joaquin League, an act which led to his suspension from organized baseball. After two years with Fresno, in which he compiled a 23-11 record, Leonard won his reinstatement and returned to the Tigers late in the 1924 season. Appearing in nine games for Detroit, Leonard went 3-3 with a 4.56 ERA.

In 1925 Leonard started 18 games for the Tigers, posting a solid 11-4 record despite a pedestrian 4.51 ERA. However, the pitcher feuded constantly with manager Ty Cobb, who had long disliked Leonard and would later claim that the southpaw was one of only two players he ever intentionally spiked during his career. As Cobb later explained, “Leonard played dirty—he deserved getting hurt.” According to Cobb biographer Charles Alexander, Cobb punished Leonard by deliberately overusing him, even after the team physician warned that the work could do permanent damage to the pitcher’s arm. When Leonard protested that his arm hurt, Cobb castigated him in front of the entire team, exclaiming, “Don’t you dare turn Bolshevik on me. I’m the boss here.”

Matters finally came to a head on July 14, when Leonard suffered the most brutal loss of his career, surrendering 12 runs and 20 hits to the Philadelphia Athletics. Despite the pounding, Cobb kept Leonard in the game for the full nine innings. Even Connie Mack, the opposing manager, pleaded with Cobb to take Leonard out of the game, reportedly saying, “You’re killing that boy.” Cobb laughed at the suggestion. Later that month, he placed Leonard on waivers and pulled strings to make sure that no other team claimed him. Leonard was particularly hurt that Tris Speaker, manager of the Cleveland Indians and a former teammate, passed on him. Once Leonard had cleared waivers, Cobb traded him to Vernon of the Pacific Coast League, but Leonard characteristically refused to report. With that, his professional baseball career came to an end.

Throughout his career Leonard had invested his money wisely, and by the time of his retirement operated a lucrative grape ranch just east of Fresno. But embittered by the manner in which he had been treated, Leonard quickly focused on exacting his revenge. Early in the 1926 season, Leonard told American League president Ban Johnson that on September 24, 1919, he had conspired with Cobb, Speaker and Indians outfielder Joe Wood to place bets on the following day’s game against the Cleveland Indians, which Speaker had promised to lose in order to help the Tigers finish in third place. (It was Cleveland’s first game after being eliminated from the pennant race.) The Tigers did win the game, 9-5, and Leonard, who did not play in the game, put up the money to bet on the outcome, receiving a modest $130 as his share of the winnings. To back up his story, Leonard produced two letters, one from Cobb and one from Wood, written shortly after the 1919 season, in which both made reference to the bets, though neither letter specifically stated what the bets had been for or whether the Indians had deliberately lost the game, as Leonard claimed.

Nonetheless, when presented with the letters, Johnson informed both Cobb and Speaker that their days in the American League were over, and after the 1926 season convinced both to resign their respective managerial positions and retire from the game. However, commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a long-time foe of Johnson’s, saw the matter differently and decided to launch his own investigation. He asked Leonard to come to his office in Chicago to answer questions, but the ex-pitcher declined the invitation. Cobb, Speaker, and Wood, in turn, declared their innocence of the game-fixing charges and demanded an opportunity to face their accuser. With Leonard stubbornly refusing to leave his California ranch, the public sided with the accused stars. “Only a miserable thirst for vengeance actuated Leonard’s attack on Cobb and Speaker,” Billy Evans declared. “It is a crime that men of the stature of Ty and Tris should be blackened by a man of this caliber with charges that every baseballer knows to be utterly false.”

Faced with a lack of evidence corroborating the game-fixing charge (indeed, Cobb, who supposedly had played the game to win, went only 1-for-5 at the plate with two steals that day, while Speaker, who was supposedly throwing the game, went 3-for-5 with two triples), as well as Leonard’s unwillingness to come to Chicago, Landis publicly cleared Cobb and Speaker of any wrongdoing prior to the 1927 season, and Cobb signed with the Philadelphia Athletics, where he concluded his Hall of Fame career, while Speaker was sold to the Washington Senators.

Leonard, meanwhile, spent the rest of his days turning his grape ranch into a multimillion dollar enterprise. For a time he lived with his wife, Sybil Hitt, a vaudeville dancer known professionally as Muriel Worth. The marriage, which produced no children, ended in divorce in 1931. With the money from his grape-growing business, Leonard enjoyed a comfortable retirement in his lavishly-furnished home, which sat on a 2,500-acre plot of land. Among his most prized collections was a record collection totaling 150,000 discs.

Leonard remained in good health until 1942, when he suffered a heart attack. To the end of his life he remained reluctant to discuss the details of his controversial career. As a nephew later told baseball researcher Joseph E. Simenic, “Many times we pleaded with him to sit down and put it on a recording—the highlights of his career—but he never felt in the mood and when he was not in the mood he was not about to do anything regardless of what it might be.”

Dutch Leonard died in Fresno of a cerebral hemorrhage on July 11, 1952. To his heirs (a sister, four nephews, and a niece) he left an estate totaling more than $2.1 million. He was buried in Mountain View Cemetery, in Fresno.

Sources

The Leonard file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Newspapers: Washington Post, New York Times, and Chicago Tribune

Alexander, Charles. Ty Cobb (NY: Oxford University Press, 1984)

Ginsburg, Daniel E. The Fix Is in: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2004)

Stump, Al. Cobb: A Biography (NY: Algonquin Books, 1996)

United States Census

Full Name

Hubert Benjamin Leonard

Born

April 16, 1892 at Birmingham, OH (USA)

Died

July 11, 1952 at Fresno, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.