September 27, 1897: Good (Beaneaters) versus Evil (Orioles)

More than a battle for the 1897 National League pennant, the contest played out at Baltimore’s Union Park was a living, breathing metaphor. To the 30,000 fans who literally broke down the park’s gates and walls to see it, and to the thousands nationally who followed telegraphed accounts in locations as distant as Los Angeles, it was the real world playing out of the eternal struggle of good vs. evil.

Few confused the assigned roles. Virtually across the nation outside Baltimore itself, the Orioles were the embodiment of all that was wrong with baseball. Led by third baseman John McGraw, shortstop Hughie Jennings, first baseman “Dirty Jack” Doyle and right fielder Wee Willie Keeler, the team managed by Ned Hanlon had since 1894 terrorized the rest of the league, sweeping to three successive pennants by both skill and intimidation. “The dirtiest ball ever seen in this country,” Boston sports writer Tim Murnane lamented of the Orioles’ style.1 A reporter in New Orleans, commenting on a spring training exhibition, had characterized McGraw as having adopted “every low and contemptible method that his erratic brain can conceive to win a play by a dirty trick.” 2

Though hardly saints themselves, the Beaneaters—three-time champions from 1891–93 before being dethroned by the Orioles—assumed the mantle of fan favorites once it became clear in 1897 that either they or the Orioles would win the pennant. Between August 27 and September 26, they combined to win 39 of 49 decisions (three games ending in ties), neither team ever leading the other by more than one game in the standings. A fated schedule ordered the clubs together for three games the final week in Baltimore. As the series opened, the Orioles held a one percentage point lead over Boston, although thanks to having played three more games the Beaneaters were actually a half game ahead in the standings.3 The frantic first two games did nothing to resolve the tension. Boston won 6-4 on Friday behind ace pitcher Charles “Kid” Nichols with a throng of 13,000 overflowing onto the field. Another 14,000 turned out Saturday, again spilling onto the field and climbing atop the outfield fence, to watch the Orioles win 6-3 and draw the race back into a virtual deadlock. The illegality of Sunday baseball merely ensured that the drama would build one more day.

Despite the fact that Monday was a work day, fans overwhelmed the tiny baseball grounds to witness the decisive game. The attendance is commonly estimated at 30,000—easily surpassing the previous record for any game—but the truth is that nobody knows how many people watched. Fans broke through the outfield gate and knocked down part of the fence to get access. Others stormed the turnstiles, erected seats on the roofs of houses across the street, or perched themselves on telegraph poles.

A delegation of more than 100 fans from Boston— the genesis of the famed “Royal Rooters”—showed up complete with a brass band to challenge the home team’s noise advantage. Thousands more crowded the streets of Boston’s “Newspaper Row” to “watch” on large play-by-play boards in a scene repeated on smaller scales in cities across the country. Nichols, already a 30-game winner, returned to the rubber on two days’ rest as did the Orioles’ Joe Corbett, who was seeking his 25th victory.

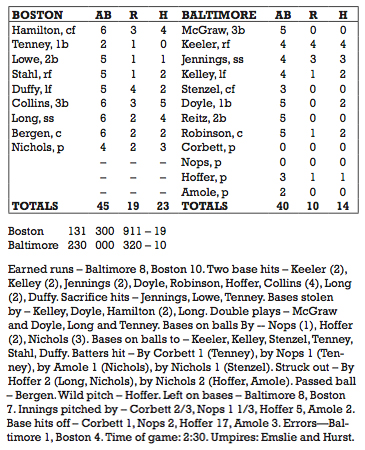

But chance had it in for Corbett. The game’s fourth batter, Chick Stahl, lined a drive off his hand that jammed several fingers. Hanlon was forced to remove his ace. The Beaneaters got a run out of that first inning, but Keeler’s base hit led to two Oriole runs in the bottom half of the inning. The lead changed hands three more times by the end of the third inning, which ended with the score tied at 5-5. In the Boston fourth, Billy Hamilton, the era’s premier baserunner, singled and stole second, Fred Tenney walked, and Bobby Lowe singled to drive Hamilton across. Chick Stahl followed with a single that produced Tenney, and an error by Wilbert Robinson allowed Lowe to score an eighth run.

Bill Hoffer, whose 22nd victory had been Saturday’s complete-game triumph, pitched scoreless ball from that point through the sixth. But by the beginning of the seventh inning Hoffer had worked 13 innings in less than two days against the league’s best offense, and he was exhausted. What ensued turned the top of the seventh into one of the most productive (or, depending on your perspective, disastrous) half innings ever played.

Hugh Duffy opened for Boston with a solid base hit. Jimmy Collins drilled a fastball into the crowd in right field for a ground-rule double, and Dutch Long’s double into the crowd in center scored both runners. When three more hits produced three additional runs, Hoffer did what in 1897 was the unthinkable: He motioned to team captain Robinson and manager Hanlon to relieve him. Both men ignored the gesture, imploring Hoffer to continue. He did, but by the time the slaughter had ended with Long’s second double of the inning, nine Boston runs crossed the plate. The champion Orioles were, for the first time since 1893, effectively unseated.

When Nichols retired the last Baltimore batter and the final score 19-10 score was posted, a remarkable scene ensued. Although the Baltimore and Boston fans had exchanged epithets all season long, they now joined on the field in a series of mutual salutes. Their bands serenaded each other with renditions of “Yankee Doodle,” “Dixie,” “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” and “Maryland, My Maryland.”4

The nation treated the outcome as something of a purgative for what were widely perceived as the game’s ills. “Never was interest keener in America’s great national game than it is today,” said the Boston Globe.5 The outcome put Boston a game and a half in front with just three to play; two victories in Brooklyn the following weekend formalized the pennant that ended the pennant run of the 19th century’s most feared and despised team at three.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 T. H. Murnane, “The Champions,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1894: 2.

2 Charles Alexander, John McGraw (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988), 39.

3 The Orioles had four games remaining on their schedule compared to Boston’s three. Due to travel problems, rained-out Orioles games in Cleveland and Louisville had not been made up.

4 “Boston On Top,” Baltimore Sun, September 28, 1897: 6.

5 “Editorial Points,” Boston Globe, September 28, 1897: 6.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 19

Baltimore Orioles 10

Union Park

Baltimore, MD

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.