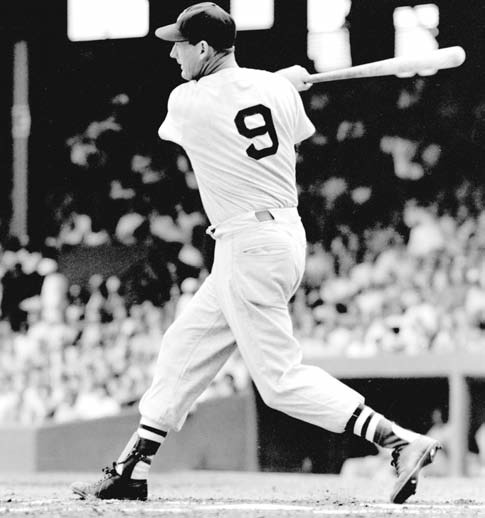

September 28, 1941: Teddy Ballgame finishes at .406

With their A’s once again mired in the American League cellar, an above-season-average 10,268 fans nonetheless found their way to Philadelphia’s Shibe Park on the last day of the 1941 season.1 A Lefty Grove Day observance celebrating their once-dominating southpaw held a degree of interest as the old-timer returned with the Boston Red Sox. But Ted Williams was also in town, his average at .39955 after months above .400, and not only the fans in Philadelphia but the baseball world wanted to see if The Kid would sit or play. If he played, would the A’s pitchers challenge him? If they did, how would Williams do, given the intense pressure he’d been under for weeks and a 1-for-4 game against Philadelphia just the day before?

From September 10 on, Williams had hit .270.2 “Everyone became a statistics expert,” Robert Creamer noted in Baseball in ’41. Red Sox manager Joe Cronin had gone so far as to mention the idea of Williams’ sitting out the final three games in Philadelphia. But “Williams insisted on playing. He’d hang in there. He’d play.”3 That decision had produced Williams’s lackluster Saturday performance and the .39955, which would round to .400, as the Sunday doubleheader loomed.

From September 10 on, Williams had hit .270.2 “Everyone became a statistics expert,” Robert Creamer noted in Baseball in ’41. Red Sox manager Joe Cronin had gone so far as to mention the idea of Williams’ sitting out the final three games in Philadelphia. But “Williams insisted on playing. He’d hang in there. He’d play.”3 That decision had produced Williams’s lackluster Saturday performance and the .39955, which would round to .400, as the Sunday doubleheader loomed.

Williams, 22, was in his third Boston season and already displaying the pugnacious attitude that led him to joust with writers and fans.4 He’d already missed a handful of games with nagging injuries and was firm. “If I’m going to be a .400 hitter, I want more then my toenails on the line.”5 “If I can’t hit .400 all the way, I don’t deserve it.”6

The shorter days of autumn heightened the shadows in cavernous Shibe Park and posed problems for hitters, even Williams. Too keyed up about the next day to remain in the team hotel on Saturday night, he recruited Red Sox clubhouse man Johnny Orlando and they embarked on a walking tour of Philadelphia drinking spots that lasted in excess of three hours. “Orlando stopped at bars for occasional sustenance as Williams, who rarely drank alcohol, sipped a soft drink outside.”7 [Most accounts say that Ted had ice cream.]

A baseball purist who had observed his share of .400 hitters since debuting in the majors in 1886, Philadelphia manager Connie Mack had instructed his pitchers to pitch to Williams rather than frustrate him with walks. First-game starter Dick Fowler and two relievers did just that.8 Williams, having been walked repeatedly in recent weeks and relishing a chance to swing, overcame his nerves and the Shibe Park shadows with a home run and three singles. The monkey was off his back; the Red Sox scored two runs in the top of the ninth to pull out a 12-11 win.

Grove, Joe Cronin’s pick to start the second game, was feted between games.9 He had broken in with Mack’s A’s 16 years before and joined select company on July 25 of this season when he won his 300th game. Grove was 41 years old, “silver-thatched and portly,”10 with a tired arm and a sore back; he was 7-6 for the season as he answered the call in his 616th major-league game.

Mack countered with Fred Caligiuri, a 22-year-old rookie right-hander from the wilds of northwestern Pennsylvania. He’d been called up from Class B Wilmington three weeks before and was 1-2.11

True to his word, Williams was once again in left field and hitting fourth. Caligiuri summarily retired Dom DiMaggio, Lou Finney, and Al Flair in the top of the first while the A’s quickly feasted on Grove in their half, scoring three runs on four hits, a DiMaggio error, and a wild pitch. Grove finally got out of the inning when catcher Johnny Peacock threw out Al Brancato attempting to steal second. When it was over, Cronin sat Grove down in favor of Earl Johnson, who went the rest of the way for Boston, giving up four runs of his own.

Williams faced Caligiuri for the first time leading off the second and raked a single. By the time he came up again in the fourth, the A’s had increased their lead to 4-0. Still getting pitches intended to get him out, Williams lashed a vicious line drive that broke a public-address speaker horn in the farthest reaches of the Shibe Park outfield, then dropped, limiting him to a double. “One writer said it was the hardest Williams had hit a ball in his three seasons with the Red Sox.”12 And it’s conceivable the shot inspired a movie scene treasured by many baseball fans.13

Caligiuri had notched two outs in the fourth before Williams’s double and stranded him, so the epic clout didn’t put the Red Sox on the scoreboard. Still nursing a shutout and now with a six-run cushion, Caligiuri won their next encounter, retiring Williams as the leadoff hitter in the Boston seventh.14

Frankie Pytlak, who had replaced Peacock behind the plate for Boston, batted for the first time to lead off the eighth and homered to spoil the shutout. Fittingly, with the 7-1, six-hit, win easily standing as the highlight of his month in the majors, Caligiuri made a curtain-call out to end the Philadelphia eighth. That was it – the game was called due to darkness.

As Shibe Park emptied in the dwindling autumn light, Williams was secure at a rounded .406, still, through the 2013 season, the last player to hit .400. Caligiuri could look forward to an offseason warmed by the memory of his last-game success. Grove, knowing the end had come, told Boston owner Tom Yawkey of his decision to retire as the two walked Yawkey’s South Carolina hunting preserve in early December.15

By 1943 both Williams and Caligiuri16 were serving in World War II, and Grove, too old for service, awaited his inevitable induction to the Hall of Fame.17 Williams was elected to the Hall in 1966.18

Sources

Creamer, Robert W., Baseball In ’41 (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 263-71.

Dwyer, Bill, “This Is the Way to Go Out Hitting,” Los Angeles Times, September 29, 2011.

Pennington, Bill, “Ted Williams’ .406 Is More Than a Number,” New York Times, September 17, 2001.

Updike, John, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” The New Yorker, October 22, 1960.

Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1941. (Acknowledgment: David W. Smith, Retrosheet).

Baseball-Almanac.com (Oldest Living Major Leaguers list)

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Kaplan, Jim, “Lefty Grove,” SABR Biography Project, sabr.org.

The author also made use of his SABR Biography Project profile of Fred Caligiuri, published at sabr.org in 2013.

Notes

1 Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1941. The A’s averaged 6,868 at home in 1941. They had attracted 11,308 for their opener on April 18 and 28,874 (nearly 6 percent of the year’s total) for a visit by the Yankees two days later. Baseball-Reference.com.

2 Williams was hitting .413 on September 10. He had been as low as .308 on May 3. Retrosheet.org.

3 Creamer, Baseball in ’41, 268.

4 “The dowagers of local journalism attempted to give elementary deportment lessons to this child who spoke as a god, and to their horror were themselves rebuked. … His basic offense against the fans has been to wish that they weren’t there,” Updike, The New Yorker, October 22, 1960.

5 Pennington, New York Times, September 17, 2001.

6 Dwyer, Los Angeles Times, September 29, 2011.

7 Pennington. Some accounts have Williams disdaining alcohol for ice cream.

8 The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Stan Baumgartner noted in his September 29, 1941, game account that “the Athletic pitchers contributed only one thing to Williams’ final splurge. They got the ball over the plate.”

9 “ ‘Well, he’s a better guy now,’ said an unnamed Athletic. ‘All he used to have was a fastball and a mean disposition.’ Connie Mack said, ‘I took more from Grove than I would from any man living. He said things and did things – but he’s changed. I’ve seen it year by year. He’s got[ten] to be a great fellow.’” Kaplan, “Lefty Grove.”

10 Baumgartner game account, Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1941.

11 Caligiuri recalled his first meeting with Connie Mack: “Right after they called me up I was sitting there on the bench. I didn’t know anybody and nobody was talking to me. Connie Mack came down the line, tossed me the ball and said, ‘You’re pitching today.’ Two years before I was in Class D, and here I was pitching in the major leagues.” Author’s telephone interview with Fred Caligiuri, April 3, 2013.

12 Creamer, 271.

13 “In The Natural, the hero, Robert Redford’s Roy Hobbs, … wore No. 9 and, in his last at-bat, smashed a row of lights with a towering home run. Williams [who wore No. 9] broke a loudspeaker horn with the double on his last day in 1941, and also homered in his last at-bat in 1960.” Dwyer.

14 Recollections differ on how the out was made. Some sources recall a fly to right, some, including the Retrosheet play-by-play, a fly to left. Caligiuri himself remembered “a pop-up that carried far enough behind the shortstop that [left fielder] Elmer Valo caught it.” Caligiuri interview, April 3, 2013.

15 Kaplan, SABR Biography Project.

16 Born October 22, 1918, Fred Caligiuri attained age 99 in 2017. With the death of Chuck Stevens on May 28, 2018, Fred Caligiuri became the oldest living former major leaguer. Baseball-Almanac.com, accessed July 20, 2018.

17 Grove was elected in 1947, his fourth year of eligibility. Baseball-Reference.com.

18 Williams’s election was in his first year of eligibility. Ibid.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 7

Boston Red Sox 1

Game 2 of DH

At Shibe Park

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.