September 3, 1869: Inter-racial baseball in Philadelphia

Frederick Douglass said no city was more prejudiced against colored people than Philadelphia.1 The black inhabitants of Penn’s City of Brotherly Love after the Civil War numbered 22,185, representing 4 percent of the population. Only Baltimore had more black residents.

Frederick Douglass said no city was more prejudiced against colored people than Philadelphia.1 The black inhabitants of Penn’s City of Brotherly Love after the Civil War numbered 22,185, representing 4 percent of the population. Only Baltimore had more black residents.

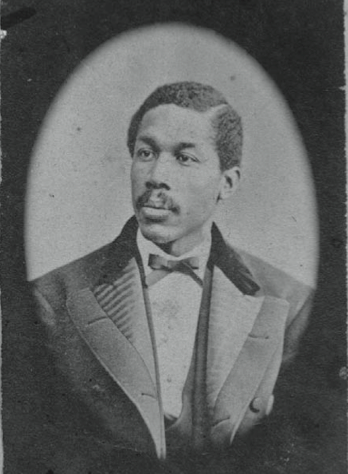

Leading Philadelphia blacks understood how education and community associations could further their advancement. A focal point of this movement was the city’s only black high school, the Institute for Colored Youth, later renamed the Banneker Institute. In addition to a rigorous curriculum, the Institute supported a number of athletic organizations.2 An esteemed graduate, later teacher/principal of the school, was Octavius Catto. An experienced cricket and town ball player, Catto became the shortstop and captain of the Institute’s baseball team. Known as the Independent ball club, Catto’s team by the spring of 1866 became one of the leading black ball teams in the city. Later that summer, because a large number of the Institute’s players were affiliated with the Knights of Pythias Lodge, the team was renamed the Pythians.

The colored community of Philadelphia had more than a passing interest in baseball. They followed both white and black local ball clubs. In 1867 the “Pyths,” as they were sometimes called, strengthened themselves by recruiting players from other black teams. Under Catto’s captaincy the team played 13 games in 1867. They went 8–3, and two games have no known results. One white reporter was so impressed by the Pythians, he described them as a “well behaved gentlemanly set of young fellows … [who] are rapidly winning distinction in the use of the bat.”3

Despite their successes, in October 1867 Catto and his teammates got a dose of reality when they applied for admission to the Pennsylvania Association of Amateur Base Ball Players. Despite being nominated by E. Hicks Hayhurst, the vice president of the Athletics ball club and the presiding president of the Association’s convention, the Pythians were denied access because of race and were compelled to withdraw their application.4

This rejection was not indicative of the Pythians’ relationship to Philadelphia’s white baseball establishment. Catto’s club scheduled games at white-controlled ball fields and had accounts with the A.J. Reach Sporting Goods Company.5 These relationships encouraged Catto to believe that social and political acceptance could be promoted by competing against “our white brethren” on the field of play.6 But there is no record that any game between white and black teams had been played to that date, and white clubs had mixed feelings about playing a black ball club. They believed that if they won, it would be expected, and if they lost their prowess would be called into question. One columnist even posed the question of whether “negroes” made better players then white men. The response was that colored players were better at “whitewashing, and in hot weather they play a stronger game.”7

In 1869 the Pythians’ challenge was accepted by Philadelphia’s oldest ball club, the Olympics, whose town ball tradition went back to 1832. Thus for the first time on record, white and black teams took the field against one another. It appears that the decision to set this game up was based on two factors. Both the Olympics and the Pythians needed the revenue drawn from gate receipts. The Olympics had not played in two months [ July 15] and had just undergone a restructuring of the ball club. Team morale and revenue were affected by these actions. If the “novelty” of a game against a local black team was a factor then the game would primarily be a financial decision.8

The same considerations influenced the Pythians. A game against the Olympics would acknowledge their existence and sustain their treasury. The Olympics also required that the contest would be played at their home field at 25th and Jefferson. Despite these conditions, this controversial match needed mediation. The key figure in the negotiations was Col. Thomas Fitzgerald, the founding president of the Athletics of Philadelphia and the owner and publisher of Philadelphia’s City Item newspaper. Fitzgerald loved baseball and used his newspaper to promote the city’s teams. He also championed equality before the law in his City Item editorials. Once the game was set in motion, he agreed to serve as the game’s umpire.

As expected a large and enthusiastic crowd assembled on Friday, September 3. It was the largest crowd to see an Olympics game since they played the Red Stockings of Cincinnati on June 19. A number of policemen patrolled the enclosure. They kept the game orderly until the last inning when spectators broke through the restraining ropes. At 2:45 p.m. the game began and the Pythians took a 3–1 lead after the first inning. In the top of the second the Olympics scored eight runs and never again gave up the lead. Catto’s team was “blanked” in three innings and to everyone’s astonishment the Olympics were held scoreless in their half of the seventh. John Cannon pitched for the Pythians and young Len Lovett threw for the Olympics. Lovett was only 17 years old and had just been recruited to be the Olympics’ pitcher. The final score was 44–23. The game took three hours and 10 minutes to play.

The Philadelphia Inquirer said the Pythians “acquitted themselves in a very creditable manner.”9

A return match was set for October 11 to be played at the Athletics field at 17th and Columbia. There is, however, no record that the game was ever played. The Pythians did go against Fitzgerald’s white City Item ball club on the 16th at the Athletics field. Fitzgerald’s three sons actually played in this game, which the City Item team lost 27–17. Another scheduled game against the white Masonic club of Manayunk had no published results.10

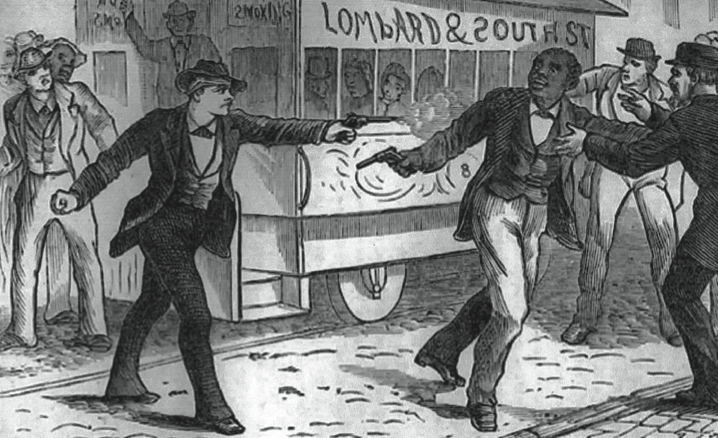

Although the Pythians played ball through 1871, their schedule was greatly reduced. Racial tensions were heightened by the passage of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution giving male Freedmen the vote, and leaders such as Catto were preoccupied with political matters. It is also possible that white-operated ball fields were intimidated by the possibility of racially-inspired violence. When Octavius Catto was gunned down on October 10, 1871 during race riots spurred on by the local mayoral elections the gains made between the races on the “field of green” did not look so substantial.

A woodcut depicting the shooting of Octavius Catto on October 10, 1871.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 Weigley, R. “The Border City in the Civil War, 1854-1865,” Philadelphia: A 300 Year History (Philadelphia, 1982), p. 386.

2 Casway, J. “Philadelphia Pythians,” The National Pastime, No. 15 (1995), p. 120-1; Casway, J. “Octavius Catto and the Pythians of Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Legacies, May 2007, Vol. 7, No. 1, p. 5-7; Silcox, H. “Nineteenth-Century Black Militant: Octavius Catto, 1831-1871,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, January 1977, p. 55-8.

3 Casway, “Catto and Pythians,” Legacies, p. 7; Casway, “Pythians,” The National Pastime, p. 121.

4 Sunday Mercury, July 21, 1867.

5 See letters, contracts, and bills of sale in Gardiner Collection, at the HSP.

6 Catto to Dr. McCullough, August 12, 1869 in ibid.

7 Sunday Mercury, September 20, 1868.

8 Ibid., December 12, 1869.

9 Philadelphia Inquirer, September 4, 1869; The Playing Ground, October 2, 1869, p. 637.

10 Sunday Mercury, August 18, 1869; September 12, 1869; September 18, 1869; October 10, 1869.

Additional Stats

Pythians of Philadelphia 44

Olympics of Philadelphia 23

Olympics Grounds

Philadelphia, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.