Graham McNamee

Red Barber described how Graham McNamee helped break the ground for him and other great baseball voices, starting in the early 1920s. “There was no lamp of experience for the pioneer broadcasters. They had no past by which to judge the future. This is what made McNamee and the others so great. Nobody had ever been called upon before to do such work. They had to go out and do it from scratch. If ever a man did pure, original work, it was Graham McNamee.”1 Though his busy schedule included many other announcing duties, in sports and beyond, McNamee’s opera-trained baritone became synonymous with fall and the World Series.

Red Barber described how Graham McNamee helped break the ground for him and other great baseball voices, starting in the early 1920s. “There was no lamp of experience for the pioneer broadcasters. They had no past by which to judge the future. This is what made McNamee and the others so great. Nobody had ever been called upon before to do such work. They had to go out and do it from scratch. If ever a man did pure, original work, it was Graham McNamee.”1 Though his busy schedule included many other announcing duties, in sports and beyond, McNamee’s opera-trained baritone became synonymous with fall and the World Series.

Thomas Graham McNamee was the son of John and Anne (Liebold) McNamee, both of Irish ancestry and Ohio residents when they married in 1885. The couple moved to Washington, DC, after John accepted a position as a legal assistant to the Interior Secretary during the Cleveland administration. Their only child was born in DC on July 10, 1888.

The family relocated to St. Paul, Minnesota, when Graham was two years old, after his dad accepted a position as a railroad attorney. A trained musician in her own right, Anne McNamee taught her son to sing by age four and play piano at age seven. Attending high school in St. Paul, Graham did well academically in languages and music, while excelling at football, baseball, and wrestling.2

After graduation, John McNamee arranged for his son’s first job as a freight clerk with the Great Northern Railroad. Graham was next employed as a deliveryman (by horse and buggy) for the Chicago-based Armour & Company. After wrecking 11 buggies in 12 months of employment, he was terminated.3

Graham’s ambitious mother was convinced an opera career awaited their son; his dad leaned heavily toward law as a profession. Family upheaval due to John McNamee’s work-related travel ultimately led to a divorce. After the split, Graham accompanied his mother to New York, where she assumed her son would receive superior vocal training. The 1920 census lists Anne as the owner of a rooming house on West 57th Street; Graham resided on the premises.

McNamee joined an opera company, there meeting aspiring singer Josephine Garrett from nearby Bronxville. The couple sang in the Dutch Reformed Church choir as their relationship blossomed. When they married on May 3, 1921, Josephine’s classically trained voice made her the more likely spouse to have a potential singing career. Yet opportunities existed for Graham too; in 1922 he received an invitation to perform at New York’s prestigious Aeolian Hall, a legitimate stepping stone for aspiring opera singers.4

McNamee placed operatic aspirations on hold, however, because he found a new job at radio station WEAF in New York in May 1923. In receipt of a notice to serve jury duty, while fulfilling his civic obligation on a beautiful spring day, McNamee decided on a long exhilarating walk during his lunch break. Selecting a route bypassing his usual diner, he chose instead to lunch at a pricey upscale establishment near the AT&T building, at 195 Broadway; the decision cost him an additional 50 cents.

McNamee paused upon noticing a mesmerized crowd listening to a radio broadcast emanating from WEAF, which was in the AT&T building. Reacting on impulse, he ventured in and upstairs to the WEAF studios. Fortuitously catching the attention of station manager Sam Ross, he boldly inquired about a position as a singer.

Ross indicated no such opening existed, prompting McNamee to mention a window sign he spotted for a staff announcer. Ross liked the appealing tone of McNamee’s voice and definitely needed help in that department. Mac was hired on the spot at a starting salary of $3 a day. His job description was to “fill in between appearances of important people.”5

Early radio announcers worked gruelingly long hours, performing a laundry list of duties around the station. Jobs included general maintenance, answering phones, chauffeuring celebrities, and improvising to fill airtime. As described by author Gerald Nachman, McNamee’s “magnetic voice and dramatic flair were tempered with an easygoing personality that set him apart from the mellifluous voices that dominated the microphones of the 1920s.”6

McNamee cut his teeth as a sports broadcaster on August 31, 1923, when assigned to announce the Harry Greb-Johnny Wilson middleweight championship boxing match. His next foray was at the Polo Grounds on September 14, where a crowd exceeding 60,000 fight patrons gathered for another famous bout, the heavyweight championship match between Jack Dempsey and Luis Firpo. Thousands more heard Major Andrew White (assisted by McNamee) describe the action on radio. This important live broadcast of a championship fight was a significant radio milestone, greatly increasing the popularity of the fledgling medium. Dempsey retained his title despite being knocked through the ropes (and landing on McNamee) in the first round.

A deluge of positive fan mail followed, attesting to McNamee’s style. “The few detractors generally commented about his slight exaggeration, but the listening audience loved the hype and couldn’t get enough of the announcer with the baritone voice. McNamee freely admitted to being an entertainer first and a broadcaster second.”7 His approach to radio was simple: “You make each of your listeners, though miles away from the spot, feel that he (or she) too is there with you in the press-stand, watching the pop bottle thrown in the air, Gloria Swanson arriving in her new ermine coat; John McGraw in his dugout, apparently motionless, but giving signals all the time.”8

McNamee’s career took another great step forward with the 1923 World Series. The excitement was electric, as crowds filled Yankee Stadium to capacity for the opener on October 10. For the third consecutive year, the Fall Classic was an all-New York affair, pitting the dominant National League Giants against the upstart Yankees, representing the American League. The latter fittingly christened their magnificent new ballyard in the Bronx by going on to win their first World Series title.

McNamee’s career took another great step forward with the 1923 World Series. The excitement was electric, as crowds filled Yankee Stadium to capacity for the opener on October 10. For the third consecutive year, the Fall Classic was an all-New York affair, pitting the dominant National League Giants against the upstart Yankees, representing the American League. The latter fittingly christened their magnificent new ballyard in the Bronx by going on to win their first World Series title.

1923 also marked the third Fall Classic broadcast over radio, the new media phenomenon. Broadcast licenses were rapidly being granted to stations all over the country; airtime was difficult to fill, prompting the coverage of unsponsored sporting events (like the World Series) as a public service. An early radio experiment had involved WJZ’s broadcast of the first game (only) of the 1921 Series. The methodology used involved Newark Call reporter Sandy Hunt phoning the action from the Polo Grounds to colleague Tommy Cowan broadcasting from the WJZ studio.

Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis assigned broadcast duties for the 1922 series to prominent sports writer Grantland Rice. Seated in the upper deck of the Polo Grounds, the respected scribe spoke into a microphone crudely perched atop a wooden plank, wired directly to station WEAF in New York. A man of few words, Rice spoke in a slow monotone, devoid of any excitement or enthusiasm. His habit of taking frequent breaks—to allegedly rest his voice—produced extended periods of dead-air silence.

New York Herald-Tribune writer William McGeehan took on the announcing duties for the 1923 Fall Classic, and Graham McNamee was hired to assist him. McGeehan walked off the job in the fourth inning of Game Three, leaving the broadcast in McNamee’s hands.9 Taking a deep breath, Mac confidently spoke into the microphone with a line that became his standard opening: “How do you do, ladies and gentlemen of the radio audience? Graham McNamee speaking.”10

At the conclusion of the 1923 Series, management at WEAF received over 1,700 positive letters, attesting to McNamee’s on-air style. The deluge of mail continued following the 1924 Series; by 1925 his popularity had grown to an astounding 50,000 correspondences received from appreciative fans.

McNamee’s broadcast of the 1926 Rose Bowl included extensive details regarding the changeable California weather, accompanied by overly thorough descriptions of attendees’ attire; game details were occasionally mentioned. Humorist Will Rogers later publicly scorned McNamee for his insignificant tangents, unrelated to sports, but the listening audience couldn’t get enough of the announcer with the baritone voice. 11

Later in 1926, stations WEAF and WJZ merged to become the National Broadcasting Company, forming a cross-country network, connected by 3,600 miles of phone lines. The official kick-off ceremony took place on November 15, 1926, with a celebratory broadcast from the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria. An estimated 10 million listeners heard Graham McNamee open the festivities by officially greeting the vast NBC audience. This milestone broadcast marked the start of what would become radio’s Golden Age. “When asked to name radio’s greatest asset, NBC president Merlin Hall Aylesworth replied — Graham McNamee.”12

Mac’s immense popularity warranted assignments to cover prominent newsmakers such as Charles Lindbergh, Admiral Richard Byrd, Neville Chamberlain, and Amelia Earhart. The Lindbergh coverage at the Washington Navy Yard resulted in an unruly crowd crashing through a Marine guard, trampling the press area. In the commotion, McNamee was knocked to the ground; miraculously unhurt, he continued broadcasting from a prone position on the pavement. 13

McNamee pursued assignments with dogged determination, often driving poorly lit back-roads, in the dark of night, to arrive for an early morning interview. If time was of the essence, Mac wouldn’t think twice about hitching a ride aboard a rickety crop duster and landing on a cornfield to conduct an interview. He once covered a college regatta while hovering above the race in a chartered plane. 14

McNamee personally kept his own schedule, which once resulted in a mistake while appearing on the lecture circuit. He was booked to conduct a speaking engagement in New Castle, Pennsylvania in May 1927. The well-publicized event was sold out at curtain time, as a filled-to-capacity audience sat in anticipation of his arrival—but he never showed. Mac had apparently jotted down the wrong date. The New Castle News published an unflattering editorial, blasting the announcer’s blatant snub of the event.

Learning of his error, McNamee took full responsibility, contacted organizers, and insisted all attendees be invited back the next evening, to enjoy the lecture at no charge. “The next day’s news took back its raspberry-laced criticism and praised the great man to high heaven.”15 Remarkably, McNamee never prepared his program in advance but depended on his extraordinary extemporaneous speaking ability to entertain his audience.16

During the span of a few weeks in the fall of 1927, McNamee was especially noteworthy. On September 22, he was behind the mike for another classic heavyweight battle, the “Long Count Fight” between Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney, who’d taken the title from Dempsey a year earlier. More than 100,000 fans—up to 150,000, by some accounts—had gathered at Soldier Field in Chicago to watch the highly anticipated rematch.

Tunney dominated for the first six rounds—but Dempsey then went on the attack. NBC estimated that 50 million people around the world were listening, “sharing the excitement in McNamee’s voice, particularly when he shrieked during the fight’s epic seventh round: ‘Some of the blows that Dempsey hit make this ring tremble! Tunney is down! From a barrage! . . . They are counting!’”17 But Dempsey lost several seconds in getting to a neutral corner. That gave Tunney an opportunity to get back on his feet and ultimately retain his title, while also ending Dempsey’s career. It was said that nine people died of heart attacks listening to McNamee’s broadcast, three of them during his blow-by-blow of the seventh round.18

The broadcaster graced the cover of Time magazine when the October 3, 1927, edition hit the newsstands. The announcer’s fame segued into his personal syndicated newspaper column, appropriately titled “Graham McNamee Speaking.” Under his byline, the announcer waxed poetic regarding news events, while providing insightful anecdotes to accompany celebrity interviews. His commentary included analysis of current events while responding to reader inquiries, often of a personal nature.

As noted, McNamee’s voice became identified with fall and the World Series. His broadcast of the Yankees-Pirates 1927 Fall Classic marked the first year a nationwide audience enjoyed the play-by-play over network radio.

At the close of the 1920s, McNamee’s style placed him at the top echelon of all radio announcers. His annual income was estimated to be in the $50,000 range, a remarkable sum at the time. The salary allowed the former out-of-work juror to comfortably reside in a vine-clad cottage atop a swanky New York penthouse.

Miscues were common (and even expected) during a McNamee broadcast. Realizing nothing could be done to correct a mistake, the broadcaster thought it best to simply admit regret and go on to the next factoid. “Once at a baseball game, he confused the players and plays to such an extent, sportswriter Ring Lardner was prompted to observe that there had been a doubleheader yesterday–the game that was played and the one that McNamee observed.”19 Quick with a pun, Mac observed a fight in the stands resulting in a pop bottle being hurled at an umpire. McNamee called it: “a ball…and a strike.”20

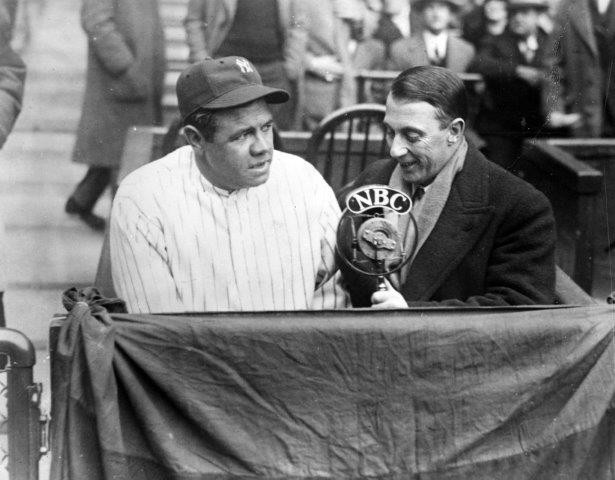

In 1930, close pal Babe Ruth opened a haberdashery shop in New York for men and boys. Serving as master of ceremonies, McNamee: “cheerfully addressed the crowd through a loudspeaker; the ever-confident salesman casually covered the lines of apparel stocked in Babe’s new retail shop.”21 Other celebrities accompanying Babe to the grand opening included Knute Rockne of Notre Dame, Yankees manager Bob Shawkey, and teammate Lou Gehrig.

McNamee’s crowded workload increased further when assigned to narrate Universal Newsreels in 1930. Josephine began referring to herself as “the original microphone widow.”22 Tabloid publications didn’t help solidify the couple’s relationship, alluding to rumors of an ongoing affair, apparently discovered by Josephine. The couple (who were childless) divorced in 1932.23

McNamee remarried on January 21, 1934, tying the knot with Ann Lee Sims, a Louisiana native and aspiring New York actress. The Washington Post reported the ceremony as taking place in Elkton, Maryland, “where the couple hurriedly motored into the little town, secured a license and were married by one of the town’s marrying parsons.”24 The bride was over 20 years younger than her new husband.

McNamee’s favorite radio gig was his stint in the early/mid-1930s as the announcer on the Texaco Fire Chief, a highly rated NBC radio program, starring veteran comic Ed Wynn. The energetic comedian essentially performed variations of his old vaudeville routines before a live, in-studio audience. In addition to handling the announcing chores, Mac also dutifully performed as a stooge to Wynn’s madcap brand of comedy.

Author Elizabeth McLeod noted, “Wynn apparently was a very insecure man. It was McNamee who calmed him down each week, McNamee who gave him the courage he needed to face that forbidding black enamel box. The two men became close friends—and McNamee’s regular-guy enthusiasm acted on the air as the perfect complement to Wynn’s manic comedy.”25

While broadcasting the National Soap Box Derby from Akron, Ohio, McNamee was behind the mike on August 12, 1935, when a young participant accidentally crashed into the judge’s stand. McNamee sustained a serious head injury after being struck by the youngster’s 200-pound racer. Recuperation and ultimate recovery required a two-week hospital stay; lingering effects of the head injury would remain with the announcer for the rest of his life.

A new generation of sportscaster began arriving on the scene, loosely following McNamee’s style, but more analytical and thorough in broadcast preparation. By 1935, Red Barber became the heir apparent to announce the World Series. Ironically, McNamee attended, solely as a spectator, seated silently next to Red during the broadcast. Barber poignantly noted in his book: “The parade had passed the pioneer that rapidly, that harshly, that remorselessly, in only a dozen years.”26

McNamee’s distinctive voice and proven ability to sell advertisers’ products made his work on network radio programs more valuable than sports reporting. In addition to being on the Wynn program, his regularly scheduled announcer slots included: Major Bowes Original Amateur Hour, Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, Treasury Hour, Millions for Defense, and The Rudy Vallee Program. Periodically Vallee gave McNamee the opportunity to step away from his announcer’s duties and perform as a featured singer.

The Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, thrust the country into war. Among the high-profile stories making headlines in the aftermath was the conversion of luxury liner Normandie into the troopship Lafayette. On February 9, 1942, in New York harbor, a blaze of unknown origin consumed the entire ship. Reporters converged on the dock area as sabotage was initially suspected. The fire was ultimately determined to be accidental, caused when welding equipment ignited a spark. Broadcasting from the cold, rainy dock area, McNamee came down with a sore throat.

Continuing to work his grueling schedule, the throat ailment developed into strep, and the announcer’s health progressively deteriorated. He entered St. Luke’s Hospital in April, where a new series of tests revealed evidence of a serious heart ailment. The golden baritone voice was permanently silenced on May 9, 1942, with the official cause of death listed as a brain embolism. Services were held at the Frank E. Campbell funeral church in New York. McNamee was survived by his second wife, Ann; they too were childless.27

Shortly before his passing, a broadcast colleague asked McNamee to identify the greatest sports moment he’d ever witnessed during his extensive career. Without hesitation McNamee responded: “Babe Ruth and the ‘called-shot’ in the 1932 World Series.”28

At the time of McNamee’s passing, The New York Times estimated “the late broadcaster uttered ten times the number of words in an unabridged dictionary during his radio career.”29 McNamee was just 53, but as Red Barber remarked, “He’d lived a thousand years.”30 The broadcaster was buried in Akron, near the location of his father’s interment.

Broadcast partner and fellow WEAF announcer Phillips Carlin commented: “His voice was the most trusted and vibrant in radio, for nearly 20 years it thrilled the people who heard it. There was never such a voice of excitement heard in this land, as that of Graham McNamee.”31

McNamee was inducted into The American Sportscasters Association Hall of Fame in 1984. The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum honored McNamee with the Ford C. Frick Award in 2016, commemorating his significant contribution to the origin of baseball broadcasting.

Acknowledgments

This biography was adapted from “Graham McNamee: Broadcast Pioneer,” which was published in the 2017 edition of the SABR annual The National Pastime. It was edited by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Warren Corbett.

Notes

1 Red Barber, The Broadcasters, New York: Da Capo Press (1970), 23.

2 Curt Smith, The Voices of Summer, New York: Carroll and Graff (2005), 9.

3 Untitled passage, Elina (Ohio) Chronicle, February 6, 1929.

4 “Graham McNamee,” Terre Haute Saturday Spectator, August 16, 1930.

5 T.R. Kennedy, “A Voice to Remember,” Baltimore Sun, April 17, 1942.

6 Gerald Nachman, Raised on Radio, New York: Pantheon Books (1998), 264.

7 Robert Weintraub, The House That Ruth Built, New York: Little, Brown and Company (2011), 301.

8 Weintraub, The House That Ruth Built, 300.

9 Stuart Shea, Calling the Game: Baseball Broadcasting from 1920 to the Present, Phoenix; Arizona: Society for American Baseball Research (2015), 363.

10 Weintraub, The House That Ruth Built, 23.

11 C. Sterling/M. Keith, The Museum of Broadcast Communications (Dearborn, 2004), 927.

12 Weintraub, The House That Ruth Built, 301.

13 “The Way We Were 1927,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, May 8, 1992.

14 Barber, The Broadcasters, 25.

15 “The Way We Were 1927.”

16 “Graham McNamee to be in City Next Friday,” Canton Daily News, January 20, 1929.

17 Earl Gustkey, “Dempsey-Tunney II: The Long Count Fight,” Los Angeles Times, September 22, 1987.

18 William Nack, “The Long Count,” Sports Illustrated, September 22, 1997.

19 “Graham McNamee,” Terre Haute Saturday Spectator.

20 Ibid.

21 “Babe Ruth Opens Broadway Shop with Ceremonies,” Moorhead Daily News, September, 29, 1930.

22 Helen Hulett Searl, “In Miniature – Mrs. Graham McNamee,” McCall’s, May 1930.

23 “Graham McNamee Gets Air, Wife Tunes in on Alimony Objects,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, February 12, 1932, 1.

24 “McNamee Marries,” Washington Post, January 24, 1934.

25 Elizabeth McCloud, “The Life and Times of Ed Wynn, The Fire Chief,” OTRR.org (Old Time Radio Researchers Group), 1999.

26 Barber, The Broadcasters, 27.

27 “Graham McNamee,” Billboard, May 23, 1942, 25. The lack of children is an inference because the obituary mentioned only Ann as a survivor.

28 Weintraub, The House That Ruth Built, 394.

29 “Graham McNamee is Dead Here at 53,” The New York Times, May 10, 1942.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

Full Name

Thomas Graham McNamee

Born

July 10, 1888 at Washington, DC (US)

Died

May 9, 1942 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.