1964 Phillies: In defense of Chico Ruiz’s ‘Mad Dash’

This article was written by Rory Costello

This article was published in 1964 Philadelphia Phillies essays

The word “daring” is associated with Chico Ruiz’s game-winning steal of home on September 21, 1964. “Insane” and “mad” are among the labels, too. But was he really so wrong? An analysis of the famous play in the National League pennant race.

“We’re playing Cincinnati. Two outs in the sixth inning, and we’re locked in a scoreless tie. Chico Ruiz on third, Frank Robinson at the plate. Suddenly Ruiz takes off. He’s stealing home! Nobody could believe Ruiz would steal home with Robinson at the plate. Guys on the Reds were screaming ‘No, Chico! No, no!’ But he was gone, baby, and he was safe. We lost that game 1-0, and it broke our hump. It was the start of our ten-game losing streak.” — Dick Allen, from his 1989 memoir, Crash

“A bonehead play of the year,” Gene Mauch railed after that ominous loss on September 21, 1964. “A stupid move for Ruiz,” catcher Clay Dalrymple sneered, 25 years later.1 Art Mahaffey, the pitcher in this astounding moment, echoed them in 2007. “It was so stupid, it was the most stupid play ever in baseball, probably. … It was so stupid, it worked.”2

“A bonehead play of the year,” Gene Mauch railed after that ominous loss on September 21, 1964. “A stupid move for Ruiz,” catcher Clay Dalrymple sneered, 25 years later.1 Art Mahaffey, the pitcher in this astounding moment, echoed them in 2007. “It was so stupid, it was the most stupid play ever in baseball, probably. … It was so stupid, it worked.”2

Not only Ruiz’s intelligence was questioned – his sanity was, too. “Insane” and “mad” are among the labels frequently attached to the play. Even his manager in late 1964, Dick Sisler, said, “He goes crazy on the bases sometimes.”3 In his 1989 retrospective series about the ’64 season, Stan Hochman of the Philadelphia Daily News wrote, “So impetuous, so implausible, so impossible to justify.”4

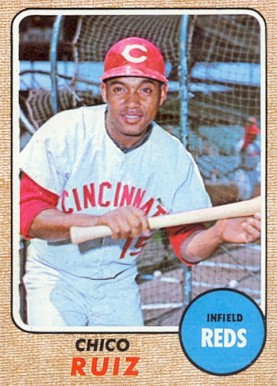

The word “daring” is associated with Ruiz’s play, too — but it’s far outweighed by the pejoratives. Had Jackie Robinson, Ty Cobb, Pete Reiser, or Rod Carew pulled off that steal, the move could well have been portrayed as brilliant in light of their stature. Ruiz, a rookie utilityman with a reputation as a joker, did not enjoy any such luster.

But was he really so wrong?

A revisionist look is in order. As John Thorn and Pete Palmer wrote in The Hidden Game of Baseball, “the two-out steal of home is the unknown great percentage play.”5 Let’s take it deeper, with some insights from two contributors to Hardball Times, Shane Tourtellotte and Dan Turkenkopf.

In 2012 Tourtellotte wrote, “The best situation for stealing home is with a runner on third only and two outs.”6 The Leverage Index is a measure of how important a particular situation is in a baseball game depending on the inning, score, outs, and number of players on base. The leverage refers to the impact on Win Expectancy, or the team’s statistical probability of winning the game. When Ruiz was on third that night with Robinson batting, it was 2.1 – i.e., high (1.0 is neutral).7

Now it’s time to calculate the break-even point: weighing failure vs. success in terms of how the outcome could influence Win Expectancy. The Hardball Times’ “Win Probability Inquirer” and a simple equation make this task much easier. One variable is the run environment (how park and league factors affect run-scoring levels).8 Flexing this assumption yields some minor differences, but for Ruiz in that spot, the break-even point was approximately 28%.9 That meant he should have gone for it if he had at least a 28% chance of success. Art Mahaffey was a righty, a minus for the runner on attempted steals of home – but he was pitching from a full windup and paying no attention to the runner.

On the face of it, therefore, the gamble looks worthwhile – especially in view of the surprisingly positive data on success rates in straight steals of home. Turkenkopf studied the 2000-2009 period because information over a longer time frame was not readily available. He also acknowledged that the sample was small: just 25 attempts, with some uncertainty about circumstances. However, 15 of the plate thieves were safe – 60%.

As Turkenkopf cautioned, though, the break-even point is simplistic. “There’s actually an additional option: Don’t attempt a steal.”10 In other words, according to the prevailing argument then and since, why should Ruiz have taken the chance when he could have stayed put and let Frank Robinson swing away? Stan Hochman put it this way in 1989: “The unwritten rules of baseball? Embedded in our DNA. You don’t steal home against a right-handed pitcher with your best hitter at the plate.”11

Robinson was absolutely a money hitter, as Table 1 shows:

Table 1: Frank Robinson with runners on third and two out

| PA | AB | H | AVG | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Runner on 3B only | 1964 | 14 | 12 | 5 | .417 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Career | 247 | 190 | 58 | .305 | 19 | 1 | 11 | 69 | |

| Runners on 3B and other bases | 1964 | 46 | 37 | 13 | .351 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 20 |

| Career | 603 | 487 | 146 | .300 | 34 | 5 | 24 | 230 |

Source: Baseball-Reference.com

His lifetime record against Art Mahaffey was 19-for-58 (.328) with two homers.

We can now introduce a concept from economics: opportunity cost – i.e., what is given up by making a choice. Table 2 shows what might have happened if Ruiz had stayed put.

Table 2: Win Expectancy for the Cincinnati Reds

Top of the sixth, two out, 0-0, Chico Ruiz on third base

Connie Mack Stadium, September 21, 1964

| As Frank Robinson came to the plate | 48.8% |

| After Ruiz stole home | 63.7% |

| If either Ruiz or Robinson made an out | 42.7% |

| If Robinson singled | 65.0% |

| If Robinson doubled | 66.3% |

| If Robinson tripled | 66.7% |

| If Robinson homered | 77.4% |

| If Robinson reached first base (via walk, HBP, etc.) and Ruiz remained at third, leaving it up to the fifth-place hitter, Deron Johnson | 50.3% |

Source: Hardball Times, Win Probability Inquirer

Even if one makes optimistic assumptions about what Robinson might have done had Ruiz not decided to steal, the weighted average Win Expectancy is only around 52%!12

After the game Ruiz himself said, “With a hitter like (Robinson) at the plate, you better make sure you make it or you get heck.”13 That’s especially because he was acting entirely on his own. Dick Sisler said, “He surprised everyone in the ballpark, including me. I saw him and said, ‘Holy smoke! What’s he doing? I couldn’t call for it (the steal) with the big man up there.”14 It’s worth noting that when Rod Carew stole home seven times in 1969, his manager – Billy Martin – was always calling the shots.15 Billy loved the straight steal of home, as well as double and even triple steals.

Ruiz was an accomplished basestealer. In the minors, he had led his league in steals five straight years from 1959 through 1963. On 9/21/64, “he got the idea when he saw Mahaffey take a long windup on the first delivery to Robinson, a strike. On the second pitch he was gone.”16 On this point, Art Mahaffey’s memory later turned faulty – he thought the count was 0 and 2. In his mind, that made Ruiz’s choice even riskier. “Robinson’s gonna swing the bat on two strikes, and he’s just going to hit you with the bat as you’re sliding in. He could kill you!”17

At least one prominent defender of Ruiz later surfaced, one who was willing to challenge the “unwritten rules.” That was Davey Lopes, an excellent basestealer in his playing days and the Phillies’ first-base coach in 2009. That August Stan Hochman wrote, “Lopes bristles when I suggest that Ruiz … committed a dumb baseball play.

“ ‘Why was it a dumb play?’ Lopes asked angrily. ‘Maybe he saw a flaw in the pitcher’s delivery?’ (Mahaffey did have an elegant, slow windup.) ‘Why was the manager [Mauch] angry at Ruiz? He should have been angry at his bleeping pitcher…

“ ‘They didn’t anticipate Ruiz stealing with Robinson up, that’s the problem. Why didn’t the manager or the coaching staff holler, ‘Watch out, he might be stealing?’ ”18 Lopes also raised the possibility of an intentional walk. If Mauch had ordered Mahaffey to put Robinson on, though, the matchup against the following batter, Deron Johnson, was perhaps less favorable. Johnson was 6-for-15 (.400) with two homers lifetime against Mahaffey.

Clay Dalrymple was certainly mindful of a possible steal. Just two days previously, in Los Angeles, Willie Davis of the Dodgers had ended a 16-inning game by stealing home off lefty Morrie Steevens, and the catcher said, “After that game I told all our pitchers to throw the ball over the middle. When that guy is breaking from third, the hitter’s concentration is broken. Just get me the ball. In that situation with Ruiz, all Art had to do was throw me the ball and we had his ass.”19

Dalrymple had said the same thing in 1989: “All he [Mahaffey] had to do was give the ball to the catcher.”20 Frank Robinson concurred with Dalrymple. After Mahaffey “vapor locked” and threw the ball wide, Robinson said, “The ball went by me before he [Ruiz] reached the plate. I think he would have been out on a good pitch.”21 Indeed, a photo of the play shows Dalrymple already turned around with Ruiz still a few feet from the plate.

Yet by forcing the action, Ruiz rattled Mahaffey and brought about a favorable outcome.22 Even Dalrymple acknowledged “the shock of it all.”23 It was a guerrilla tactic right out of the Cobb or Jackie Robinson playbook. Even with the great Frank Robinson at the plate, it was not a bad percentage move. In blackjack, a card counter would likely have said, “Hit me.” A Texas Hold’em player might call it a “semi-bluff.” Either through well-honed instinct or his baseball savvy, in a flash Chico Ruiz seized the opportunity and won the payoff. “It just came to my mind,” Ruiz said. “In this game, you either do or you don’t.”24

RORY COSTELLO never had a chance to go to Connie Mack Stadium but has enjoyed other visits to Philadelphia over the years. The thought of a Tommy DiNic’s roast pork sandwich makes him want to go back. Rory lives in Brooklyn, New York, with his wife Noriko and son Kai.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to SABR member Shane Tourtellotte and to Dan Turkenkopf for showing how to quantify Ruiz’s steal and for their review of the analysis in this article.

Sources

HardballTimes.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Stan Hochman, “Clay Dalrymple,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 17, 1989.

2 Josh Moyer, “Phillies’ collapse of 1964 is still on Mahaffey’s mind,” The Morning Call (Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania), July 7, 2007.

3 “Ruiz’s Steal Shocks Phils – and Reds,” Associated Press, September 22, 1964.

4 Stan Hochman, “Art Mahaffey,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 17, 1989.

5 John Thorn and Pete Palmer, The Hidden Game of Baseball (New York, New York: Doubleday, 1984), 159.

6 Shane Tourtellotte, “And that ain’t all, he stole home!” Hardball Times, March 2, 2012 (http://www.hardballtimes.com/main/article/and-that-aint-all-he-stole-home/).

7 The Leverage Index was created by Tom Tango. Chart available at http://www.insidethebook.com/li.shtml.

8 The Win Probability Inquirer may be found at http://www.hardballtimes.com/thtstats/other/wpa_inquirer.php. In this analysis, the run environment assumption is 4.0. That’s right in line with the National League average of 4.01 for 1964, according to figures available at Baseball-reference.com. Connie Mack Stadium had a park factor of 98, meaning it favored pitchers very slightly.

9 As seen in Table 2, the Reds had a 48.8% chance of winning the game once Ruiz reached third. Successfully stealing home raised that to 63.7%. If Ruiz had been thrown out, the chance of winning would have dropped to 42.9%. The break-even point is the value of the failure event divided by the spread in value from success to failure. Or, in this case, (42.7-48.8)/(42.7-63.7), roughly 28%.

10 Dan Turkenkopf, “Stealing a Run,” Hardball Times, May 22, 2009 (http://www.hardballtimes.com/main/article/stealing-a-run/).

11 Stan Hochman, “The unwritten rules of baseball,” Philadelphia Daily News, August 3, 2009.

12 In this best-case scenario, the outcome of Robinson’s plate appearances is: makes an out (50%), hits a homer (6%), gets another kind of base hit (26%), and reaches base by other means (18%).

13 “Ruiz’s Steal Shocks Phils – and Reds.”

14 Ibid.

15 Marty Ralbovsky, “There’s No Catching a Thief Like Carew,” Newspaper Enterprise Association, August 6, 1969.

16 “Ruiz’s Steal Shocks Phils – and Reds.”

17 Hochman, “Art Mahaffey.”

18 Hochman, “The unwritten rules of baseball.”

19 William C. Kashatus, September Swoon (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004), 124.

20 Hochman, “Clay Dalrymple.”

21 “Ruiz’s Steal Shocks Phils – and Reds.”

22 Dancing off third base to induce a balk is another related strategy in these circumstances.

23 Hochman, “Clay Dalrymple.”

24 “Ruiz’s Steal Shocks Phils – and Reds.”