The Day the Phillies Went to Egypt

This article was written by C. Paul Rogers III

This article was published in Fall 2010 Baseball Research Journal

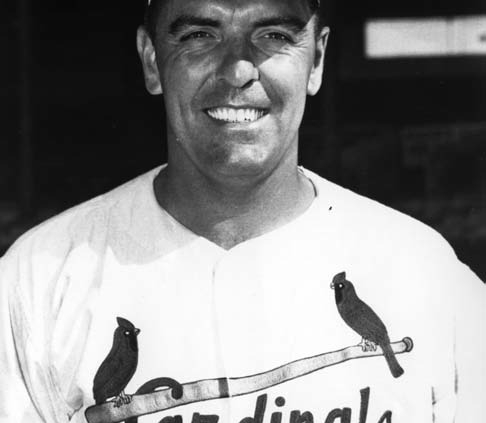

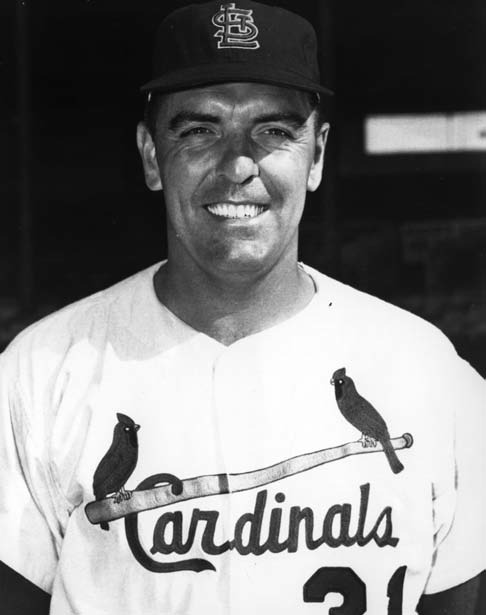

In the spring of 1947, a seventeen-year-old southpaw named Curt Simmons was the hottest amateur prospect in the country. Fifteen of the sixteen major league teams were chomping at the bit to sign Simmons as soon as he graduated from high school in June. Phillies general manager Herb Pennock dubbed him “a second Rube Waddell” and sportswriters were touting his curveball as the best since Bob Feller’s.

Simmons had earned the title Phenom when he was only sixteen. That summer, 1945, he pitched the Coplay American Legion team to the first of two consecutive Pennsylvania state junior crowns. His mound prowess earned him selection to an American Legion all-star game in Shibe Park in Philadelphia, where he struck out seven of the nine hitters he faced in three innings. That performance led to his selection later in the summer to the East–West American Legion All-Star game in the Polo Grounds in New York City. Babe Ruth managed the East team, for which Curt played, against Ty Cobb, who managed the West. Simmons was probably one of the last to pitch to Ruth. The Babe still liked to get his swings and would jump in during batting practice and take a few cuts against Curt, once hitting a ball onto the roof of the Polo Grounds. During the week leading up to the August 28 contest, Simmons and the other hurlers also came under the tutelage of the great lefty Carl Hubbell.

Simmons was from the small Lehigh Valley burg of Egypt, population well under one thousand. The Legion All-Star game was Simmons’s first trip to the Big Apple and his first time even to ride an elevator. When the game arrived, Curt started and pitched four innings before moving to the outfield, his position in high school when he wasn’t pitching. He singled in a run and then in the ninth lashed a triple to drive in the run that cut the West’s lead to one run, 4–3, and then scored the tying run from third. The East went on to win 5–4 and Simmons was named the game’s MVP. Afterward the Babe advised him to switch to the outfield because of how well he hit. (Simmons had in fact batted .465 his senior year in high school, with 20 hits, including two homers, three triples, and six doubles in 43 at-bats.) Ruth, of course, knew something about giving up pitching for full-time outfield play, but Simmons stuck to pitching.

In Simmons’s senior year of high school in 1947, he struck out 102 batters and gave up only 12 hits in 431?3 innings. He threw two no-hitters, three one-hitters, and two four-hitters in leading his Whitehall High School nine to a third straight Lehigh Valley title. In the game against Quakertown on April 8, he whiffed 20 of the 21 batters he retired.

Simmons was in a position to sign for a record bonus, and the neighboring Phillies were hoping to win the bidding war. Long the doormats of the National League, the club was in the midst of a turnaround because of the deep pockets of Bob Carpenter Sr., who had purchased the club during the war for a reported $400,000. Carpenter was a former vice president at DuPont Chemicals who was married to a DuPont. Carpenter named his 28-year-old son Bob Jr. club president, with instructions to spend money to make the Phillies a contender.

Cy Morgan was a Phillies scout from Allentown who had closely followed Simmons throughout his high-school and Legion career. He had become friends with Simmons’s parents, and together they hatched a plan to bring the Phillies to Egypt for an exhibition game so that Curt could show his wares against majorleague opposition while pitching for the town team. Simmons’s father Larry was a cement-mill worker who, in his effort to maximize his son’s value, was taking a calculated risk. If Curt pitched well, his stock would rise and so would the bidding war. If he got ripped or was wild, his stock would fall.

In response, the Phillies understood that the price for Simmons might rise or fall but exacted a promise from the elder Simmons that, no matter what, the family would give the Phillies the final opportunity to bid after all the other teams. That is, the Phillies were to have the last shot in exchange for sending their team to Egypt for an in-season exhibition game.

So on Monday, June 2, 1947 the Phillies journeyed to Egypt to play a 5:30 P.M. game against the town’s amateur team from the aptly named Twilight League. The Phillies players were not at all happy about playing a game on an off-day in a podunk town against a wild young left-hander at twilight on a field without lights. While the game was billed as a fund-raiser for the town’s newly constructed Egypt Memorial Park, it was clear to all that the Phillies would have remained in Philadelphia but for the courting of the young Curt Simmons.

General manager Herb Pennock, president Bob Carpenter, and Cy Morgan also attended, underscoring the importance of the evening. So did scouts from about every other major-league organization. Phillies manager Ben Chapman fielded a lineup made up of about half of his regulars, including outfielders Del Ennis and Johnny Wyrostek, first baseman Howie Schultz, second baseman Lee Handley, and third baseman Jim Tabor. With the exception of Ennis, the Phils’ lineup was not exactly Murderers’ Row, but they were a big-league ballclub with a 17–23 won–lost record (although they would fade to 62–92 and a seventh-place finish, 32 games behind the pennant-winning Brooklyn Dodgers).

The locals expected a crowd of four thousand. Actual paid attendance was a robust 6,282, as fans from throughout the Lehigh Valley drove to Egypt for the evening. The game turned out to be a corker and it is hard to imagine that anyone went home disappointed. Simmons started with a bang, striking out Jack Albright and Wyrostek in the top of the first. In the second, Tabor touched Simmons for a double. A single and two costly errors followed, to give the Phillies two unearned runs and a 2–0 lead. The home side came back, however, and got to Phillies starter Dick Mauney for four runs in the bottom of the third to take a 4–2 lead.

The Phillies scored an earned run in the top of the fourth on a double by Schultz and a single by Handley to close to 4–3. There the score stayed until the eighth inning, as Simmons scattered five hits through the first seven. More impressive were his nine strikeouts, better than one an inning—and all this from a youngster only two weeks past his eighteenth birthday.

Del Ennis was the first batter in the eighth. He hoisted to left-center field a high fly that both center fielder Freddie Kimock and left fielder Nat Kemmerer drew a bead on. They didn’t draw a bead on each other, however, and collided head-on just as both were about to make the catch. The ball bounded free and Ennis ended up at third with a triple. Kimock was knocked cold while Kemmerer suffered a gash on his forehead from the scary collision. The game was delayed for about ten minutes while medical personnel attended to both players.

When the game resumed, Phillies left fielder Buster Adams rapped a single to center, sending Ennis home with the tying run. Simmons bore down and retired Emil Verban and Hugh Poland on groundballs. With two outs, the go-ahead run was now on third. Sparing no quarter, manager Chapman sent Schoolboy Rowe up to pinch-hit for Howie Schultz. Rowe, a veteran pitcher, was also a decent hitter who would pinch-hit more than a hundred times in his career. The young southpaw proceeded to challenge Rowe, who swung at and missed three consecutive pitches to end the inning.

Neither team could score again, and the authorities determined after nine innings were completed that it was too dark to continue, so the game ended a 4–4 tie. Simmons had fanned 11, walked three, and given up seven hits in his nine-inning complete game. His teammates didn’t help much, committing five errors behind him and letting in two unearned runs.

After the game the Phillies were feted to a BBQ dinner before heading back to Philadelphia, where Schoolboy Rowe was to pitch against the Cincinnati Reds the next evening. Simmons, meanwhile, prepared to attend his high-school graduation that Friday, while the bidding for his services increased.

Under baseball’s bonus rule at the time, a player who had signed for a bonus of more than $6,000 could play the first year in the minors but after that had to remain on the club’s big-league roster unless he cleared waivers before being sent down. So Simmons would, under the bonus rule, be able to pitch in the minor leagues during the 1947 season, but, if he signed for more than $6,000, his team would have to keep him on the big-league roster or risk losing him to a waiver claim in 1948 or thereafter.

After Simmons’s performance against the Phillies, the field narrowed to the Phillies, the Red Sox, and the Tigers, all of them presumably willing to spend big money and to carry a skinny teenaged southpaw on their roster. The Red Sox upped the ante to $60,000, and, true to his word, Larry Simmons gave the Phillies the last bid. He told Cy Morgan that Curt would sign for $65,000. Morgan got the go-ahead from Herb Pennock and Bob Carpenter, and the deal was done. Simmons’s bonus was the highest ever paid up to then, breaking the unofficial record of the previous year when the New York Yankees paid Bobby Brown, who was in medical school at Tulane, $60,000 to play professional ball.

The Phillies sent Simmons to the Wilmington Blue Rocks of the Class B Interstate League, since he was not tied to the big-league roster until the next season. He made his professional debut on June 20 against the Lancaster Red Roses and won 7–1, striking out 11, walking four, and scattering seven hits. In 18 starts for the Blue Rocks, Simmons won 13 and lost 5, striking out 197 in only 147 innings. He allowed only 107 hits and compiled a 2.69 earned-run average. It was a most impressive beginning, although Simmons was sometimes plagued with bouts of wildness, once walking 13 in a game against the Hagerstown Owls.

The Phillies had Simmons join the major-league team after the Interstate League season was completed. They started him in the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds on the last day of the 1947 season. The Giants would finish in fourth place but would set a majorleague record for home runs with 221. The Phillies lost the first game. The second was played late in the afternoon. Giants slugger Johnny Mize was tied with Ralph Kiner for the home-run lead with 51, so Giants manager Mel Ott batted Mize first in the order, to maximize his number of plate appearances. Simmons kept the home-run tie intact, limiting Mize to a broken-bat single to left in five at-bats.

All told, Simmons struck out nine and scattered five hits, pitching the Phillies to a 3–1 victory. He shut out the Giants for the first eight innings before New York scratched out a run in the ninth. “The shadows were coming in,” Simmons recalled, “because it was the second game, so it was a nice set up for a hardthrowing left-hander who was a little wild.”

Not surprising, even for a phenom, is that the teenage Simmons struggled in 1948 and 1949 with the Phillies, with wildness often leading to his downfall. In fact, in one start in 1948 he walked 12 Giants. He then came into his own in 1950, helping lead the Whiz Kids to the National League pennant, winning 17 games by August, when his National Guard unit was called to active duty. Simmons was forced to miss the World Series, which had a lot to do with the Yankees’ sweep in four tightly fought pitchers’ duels.

He would come back from military service in 1952 and, although frequently battling arm trouble, go on to have a distinguished twenty-year career in the major leagues, posting 193 wins against 183 losses. He reemerged on the national scene in 1964 when at the age of 35 he posted an 18–9 won-loss record to help lead the St. Louis Cardinals to the National League pennant (although they got help from the monumental collapse of the Phillies, his old team, in the last ten days of the season — see Bryan Soderholm-DiFatte’s article “Beyond Bunning and Short Rest” in this same journal.)

Simmons started Game 3 of the World Series and held the slugging New York Yankees at bay for eight innings, surrendering only four hits and a single run before leaving for a pinch-hitter with the score tied 1–1. Unhappily for the Cardinals, Mickey Mantle hit what is now known as a walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth off Barney Schultz to win it for the Yankees. Simmons also started Game 6 and pitched well, leaving the game in the seventh inning down 3–1 in an eventual 8–3 New York win.

Fourteen years after missing the 1950 World Series, Simmons was able to pitch in one. But it all started in 1947 in the little hamlet of Egypt, Pennsylvania, when the Phillies came to town.

C. PAUL ROGERS III is the coauthor, with boyhood hero Robin Roberts, of “The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant” (Temple, 1996) and, with Eddie Robinson, of Robinson’s memoir “Lucky Me: My Sixty-Five Years in Baseball” (Southern Methodist University Press, forthcoming). He is president of the Hall-Ruggles (Dallas–Ft. Worth) chapter of SABR, but his real job is as a law professor at Southern Methodist University.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Gregory Ivy for his cheerful assistance in gathering old microfiche materials in support of this article.

Sources

Allentown Morning Call, 10 April 2008, C2; 15 August 1999; 2 June 1947, 14; 3 June 1947, 16; 4 June 1947, 13.

Bethlehem Globe-Times, 3 June 1947, 14.

Curt Simmons, interview, conducted by author, 1993.

Lieb, Frederick G., and Stan Baumgartner. The Philadelphia Phillies. 1953. Reprint, Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2009.

Marazzi, Rich, and Len Fiorito. Baseball Players of the 1950s: A Biographical Dictionary of All 1,560 Major Leaguers. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004.

Paxton, Harry. The Whiz Kids: The Story of the Fightin’ Phillies. New York: David McKay, 1950.

Philadephia Inquirer, 2 June 1947, 22; 3 June 1947, 24.

Porter, David L., ed. Biographical Dictionary of American Sports—Baseball. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Roberts, Robin, and C. Paul Rogers III. The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant. Philadelphia: Temple Univiversity Press, 1996.

Westcott, Rich, and Frank Bilovsky. The New Phillies Encyclopedia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993.