Notes Related to Cy Young’s First No-Hitter

This article was written by Brian Marshall

This article was published in Spring 2016 Baseball Research Journal

Next to a perfect game, the no-hitter may be the most alluring event in baseball, attracting the attention of researchers, historians, and fans alike. Historians are keen to understand every detail related to a no-hitter—easily done for recent games, but not for the games of the nineteenth century. We were told in the movie Field of Dreams that “the one constant through all the years has been baseball,” and while that may be true in general, it certainly isn’t true in terms of the level of detail. The information resources of the time were typically only the newspapers that covered the game, and their attention to detail not only varied but information often wasn’t complete.

Case in point are the various articles published regarding Cy Young’s first no-hitter, which provide conflicting, incorrect, and incomplete information. Given the stature of Cy Young in the history of Major League Baseball, anything that advances our know-ledge of such a significant performance in his career is of interest. This article compiles the first known “play-by-play” for this game in order to clarify the proceedings on an inning-by-inning basis. The intent is not to discuss Cy Young’s pitching but to clarify the events of the no-hitter and improve the historical record.

Case in point are the various articles published regarding Cy Young’s first no-hitter, which provide conflicting, incorrect, and incomplete information. Given the stature of Cy Young in the history of Major League Baseball, anything that advances our know-ledge of such a significant performance in his career is of interest. This article compiles the first known “play-by-play” for this game in order to clarify the proceedings on an inning-by-inning basis. The intent is not to discuss Cy Young’s pitching but to clarify the events of the no-hitter and improve the historical record.

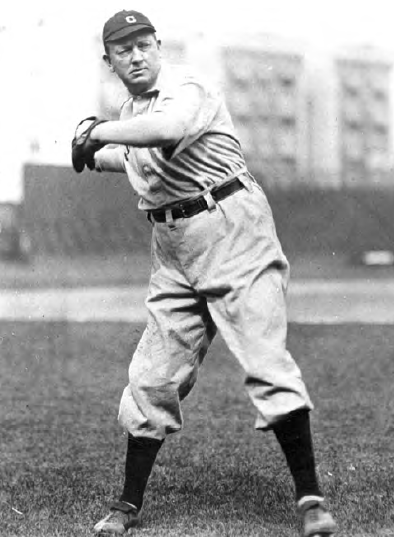

Denton True (Cyclone, Cy for short) Young pitched three no-hitters in his career, one of which (May 5, 1904) was the first perfect game in American League history and also the first in the majors at the present pitching distance.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

That Saturday was fair, about 70 degrees, with brisk northerly winds for the first game of a doubleheader at League Park in Cleveland, Ohio.7 The game started at one o’clock local time with the Reds at bat. The game featured six future Hall of Famers in Cy Young, Jesse Burkett, and Bobby Wallace for Cleveland, and Jake Beckley, Bid McPhee, and Buck Ewing for Cincinnati. Ewing was the manager of the Reds at the time.

Often the detailed information in the lower portion of the boxscores of the late nineteenth century mentioned the number of bases on balls and strikeouts for a given pitcher, but didn’t always identify the batters that they applied to. To add even more spice to the mix, the game write-ups could be misleading.

Take, for example, the small blurb ahead of the game boxscore in Sporting Life which states, in reference to the Cincinnati baserunners: “Only four men got to first, all on errors.” While it is true that only four men reached first base, it is inaccurate that they all reached on errors. One of them reached on a base on balls as indicated right below that same boxscore: “First on Balls—By [sic] Young 1, by Rhines 4.”8 This sort of contradiction was not uncommon in the published material of the time. The article covering the game often did not jibe with the boxscore statistics.

To identify which players struck out and walked in the game, I not only studied the newspaper boxscores, I also solicited the ICI (Information Concepts Incorporated) data.9 The Cleveland Leader newspaper coverage proved to be extremely useful in that it not only filled in the holes, but brought my attention to a set of errors in the boxscore.10

All of the boxscores that I had seen— both published at the time and afterward—indicate eight hits for Cleveland and 30 at bats. These totals are correct but there was an error in how the hits were credited to two of the Cleveland players, Cupid Childs and Cy Young. The boxscores incorrectly list Childs with two hits, not one, while Young actually had one hit not zero. (See the corrected boxscore in the online appendix.)

The Leader states the following:

In the fourth Pickering walked, Belden beat a pretty bunt, Zimmer sacrificed, and on Young’s infield drive Pick was caught at the plate. Burkett’s single scored Belden. Young was out trying for third on it.11

The description of Young’s hit as an “infield drive” may have been a play on words since the Cincinnati Enquirer referred to the hit as a “tap.”12 Young’s fourth-inning hit could have been a fielder’s choice, much like Belden’s could have provided the situation for a fielder’s choice. Unfortunately, the newspaper articles do not specify who fielded Young’s hit, nor do we know where the infielders were standing at the time, which makes it difficult to say whether Young could have reached first base prior to the throw getting there. We also do not know whether the ball would have been fielded cleanly in time to make the throw to first, not to mention that it may have been a situation where the only put-out that was possible was at home plate.

Since Pickering was not forced at home, that was possibly a tougher play since the tag had to be applied, while Young at first would have required no tag. Young did, in fact, reach first base—hence it is presumed the play to get Young out at first was not a given and Young should be credited with a hit.

In comparing the Belden hit in the fourth with the Young tap, it is possible the hits may have been similar in nature with the only difference being there was a play at the plate associated with the Young hit while there was a possible play at second base associated with the Belden hit. I constructed an inning-by-inning play-by-play for the game which documents each of the plate appearances as well as each of the outs. (See play-by-play in the online appendix.)

The play-by-play confirms that Childs had one hit, a double in the first inning, not two, which presents a dilemma regarding the Young hit. If Young’s hit is considered a valid hit then two corrections must be made to the boxscore: 1) the hits for Childs would change from two to one and 2) the hits for Young would change from zero to one.

I was able to validate each of the other hits for Cleveland. Belden and O’Connor each had two, Childs one—the only extra base hit in the game, and Burkett, Young, and Pickering each had singles for a total of eight Cleveland hits. I also reviewed the ICI game-by-game data sheets for both Childs and Young to understand how ICI assessed them. As expected, their data were consistent with that of the typical newspaper boxscore: two hits in three at bats for Childs and zero hits in three at bats for Young. At the very least, if Young’s hit is not considered a valid hit, it is still necessary to change the Childs hits, reducing Cleveland’s hits to seven, not eight.

The game coverage in the newspapers does not indicate any double plays, which further validates Childs having only one hit. Otherwise there would have to have been an additional Cleveland batter. The Cleveland Leader game coverage was another example of the boxscore not reflecting the written coverage of the game. For whatever reason, the boxscore data didn’t reflect the written account of the game. Possibly the person who wrote the game coverage wasn’t the person who compiled the boxscore.

I was also interested to validate the number of at bats for Cincinnati in relation to the number of baserunners. The play-by-play made this a very simple job since Cy Young only faced 29 batters, equivalent to plate appearances. In fact, Young never faced more than three batters in a single inning except in the sixth, when he faced five batters. Of the 29 plate appearances, one of them was walked, Billy Rhines in the sixth inning, which meant there were only 28 actual at bats.

Regarding the Cincinnati baserunners, there were only four of them throughout the whole game. Three reached on errors—Bug Holliday twice and Tommy Corcoran once—and as mentioned Rhines was walked. Holliday reached on errors in the fourth inning and sixth. In the fourth he was put out when he tried to steal second base and in the sixth he was left on base. Corcoran reached on an error in the fifth inning, stole second base, and was put out trying to steal third.

Only two Cincinnati baserunners managed to reach second base and none got as far as third. Two Cincinnati baserunners were left on base, Rhines and Holliday, both in the sixth. In comparison, the play-by-play stated Cleveland only left four men on base, not five as the published boxscores indicate. The men left on base were McKean in the first inning as the result of an error, Belden and Zimmer in the second inning after being walked, and Burkett in the fourth inning as the result of a hit.

Some drama ensued regarding whether the two times Holliday reached base should have been scored as hits or as errors by Bobby Wallace, third baseman for Cleveland. The Cleveland Leader stated the following:

Only four visitors reached first base during the game. Rhines drew the lonely gift, a very bad throw by McKean, after a very easy chance gave Corcoran a life, and Holliday was twice safe on errors by Wallace. One was a slow grounder which Bobby got his hands on, but let roll past him to left field, and the other was a sharp-hit drive which Wallace grabbed in wonderful style, but threw wild to first, pulling O’Connor five feet off the bag. Had the throw been good, Holliday would have been an easy out. This last chance was the only approach to a hit which the Reds got, and it was by no means near enough to mar Young’s great record.13

The Cleveland Plain Dealer reported it thus:

That Cy’s arm was in old time form this result shows and nobody ever saw better ball pitched since ball pitching began. The nearest thing to a base hit was a sort of scratch that Wallace would have taken had he not considered it too easy; as it was it got through him. Again Holliday hit a hard one at Wallace but he knocked it down. It fell at his feet and he had plenty of time to throw the runner out but his throw took O’Connor off the bag. Besides these cases there was not even a suspicion of a hit and besides this pitching record the game was featureless, at least all other features faded into insignificance.14

The Cincinnati Enquirer used the exact wording as that in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, formatted slightly differently, while the following is from a separate section entitled “Coming Home”:

Holliday says Young’s record was not so much, and that the Cincinnati team should have been given two hits. One of the errors given to Wallace was a very close decision. One ball went through Wallace’s legs on bad bound [sic]. It was a slow ball and Wallace touched it. Wallace admitted after the game that he should have had it.15

The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune stated the following:

Holliday was the only man who made even a suspicion of a hit, and he never got to second. He hit a couple of hot ones to Wallace, but Bobby should have had both of them. He stopped a good drive, but threw it wild, and then allowed a slow one to get through him.16

Sporting Life dated September 25, 1897, ran the following article:

FORGOTTEN HOW TO BAT

The Reds appear to have forgotten all they ever knew about the use of the bat. They didn’t try to bunt; they didn’t try to place hits over the infielders’ heads; they didn’t even try to “chop the ball”—a trick that a Baltimore critic asserts the Birds invented last year. Instead they stood up very a la the Quakers and banged wildly away at the ball in a desperate effort apparently to knock it into the next county. As a result the number of pop flies sent up to the infielders was as many in each game as the put-outs usually credited to a first baseman.

“CY’S” GREAT PITCHING

This weakness was very apparent in Friday’s game, when Wilson pitched, but it was even more glaringly shown in the first game Saturday, when Cy Young made his great record of shutting out the Reds without a base hit. The rail splitter had remarkable speed, and kept the ball over the heart of the plate, but the visitors did not make even an effort at scientific work, thus making the great pitcher’s work much easier.

MANLY WALLACE

During this game the nearest approach to a hit was made in the seventh [sic], when Holliday hit to Wallace. The ball went straight at Bobby, but the little third baseman let it go through his hands, and roll into the field. It could have been given a hit if for any reason it was desired to boost Bobby’s fielding average, but Wallace is not seeking that kind of glory. “It was my error, and it was an inexcusable one,” said Wallace after the game. “I was playing in the right spot for Bug, and the ball came straight at me, but in some way got through me. I should feel guilty if that was charged up against “Cy” as a hit after his wonderful work.17

The Browning book stated the following:

Critics carped that Cy Young got a break from the official scorer on a ball that Bobby Wallace threw away. Others, however, disagreed, and Wallace himself declared the error call to have been correct. In any case, Young’s first no-hit effort—also the first by anyone in four years in the major league—was a brilliant accomplishment against a fine Cincinnati team.18

There is mention in the literature record of the hits by Holliday being originally scored as hits then later changed to errors. The following passage is from the Westcott and Lewis book:

The only sour note in the no-hitter was the fact that Holliday was credited with singles on the two balls Wallace failed to field cleanly, but the hits were changed to errors in the eighth inning.19

Regarding the mention of the errors being changed in the eighth inning, none of the articles published at the time of the game made any such mention or hinted that that was the case. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, it just means it wasn’t common knowledge that it happened. Whether or not the scorer actually did credit Holliday with hits initially then, apparently in the eighth inning, changed the scoring to indicate errors for Wallace may not be as intriguing as it may appear, or even very significant for that matter.

In the game today, and while watching a telecast, it is not uncommon for a play to be scored one way at the time it occurred then later in the telecast the announcer will say that the scoring on the play had been changed. It happens and we simply accept it regardless of our personal opinion, so why should we be surprised that a scorer may have changed the scoring on a play back in 1897?

Another perspective is that the game was played in Cleveland and it is possible there may have been some home team bias from a scoring perspective. The Kermisch article suggests that Cy Young’s first no-hitter may not have been a genuine no-hitter, based on comments by none other than Cy Young himself.20

The Young no-hitter of 1897 was actually an improvement on his best one-game performance during the 1896 season, when he pitched the National League’s only one-hit game on July 23 against the Philadelphia Phillies.21, 22, 23 That game came within one out of being a no-hitter when Ed Delahanty, playing first base and batting third in the order, managed a clean hit to short right field in the ninth after Cooley and Hallman had flied out. The Philadelphia Public Ledger said that “Cooley had been robbed of the first hit of the game by Burkett.”24 It is purely speculative, although plausible, that, due to the Delahanty reputation, the outfield may have been playing back, which allowed the ball to land in short right field.

A general note related to Cy Young’s perceived value in 1897, although probably not surprising to readers, was that there had been some dickering for Young’s services. The Baltimore Sun stated the following:

BOSTON, Aug. 26.—The Boston club has been after Pitcher Willis, of the Syracuse club, but would not pay $3,000, the price asked for him. The directors are crazy to get Pitcher Cyrus [sic] Young, of Cleveland, and it would not be surprising if $10,000 were paid for him, so anxious is Boston to win the pennant.25

One aside: I found it interesting that while in the modern game it is common for broadcasters to talk about pitch speed and pitch total, those same metrics were apparently also of interest to some in the nineteenth century. Regarding the pitch total there was mention in Sporting Life: “In a full-nine inning game a League pitcher will average 115 pitched balls.”26 And regarding pitch speed, the Providence Sunday Star stated that a Pud Galvin pitch had been measured at 2/5 of a second with a Longines chronograph, which calculates to a speed of 93.75 miles per hour based on a catcher distance of five feet behind home plate.27

In summary, this article has presented a number of areas where information about Cy Young’s first no-hitter was lacking, conflicting, or incorrect, as follows:

Sporting Life: the game write-up is in conflict with boxscore.

The Cleveland Leader newspaper coverage: the game write-up is in conflict with boxscore.

The Cleveland Leader newspaper coverage: Childs 2 or 1 hits, Young 0 or 1 hits.

The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Cincinnati Enquirer, Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, and Sporting Life: the game articles lacked sufficient detail regarding play description, leaving play interpretations ambiguous.

The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Cincinnati Enquirer, Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, and Sporting Life: these outlets inconsistently reported the issue regarding Wallace’s errors/Holliday’s possible hits.

Westcott and Lewis’s book and Kermisch report that hit(s) were changed to error(s) during the course of the game.

BRIAN MARSHALL is an Electrical Engineering Technologist living in Barrie, Ontario, Canada and a long time researcher in various fields including entomology, power electronic engineering, NFL, Canadian Football and recently MLB. Brian has written many articles, winning awards for two of them. He has two baseball books on the way on the 1927 New York Yankees and the 1897 Baltimore Orioles. Brian is a longtime member of the PFRA. While growing up, Brian played many sports. He aspired to be a professional football player but when that didn’t materialize he focused on Rugby Union and played off and on for 17 seasons.

Related link

Author’s Note

Team names and the spelling of player names was based on that as listed on Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 David Southwick. “Cy Young” in New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans, edited by Bill Nowlin. Phoenix, AZ: Society for American Baseball Research, Inc., 2013, 173–77.

2 Bill James and Rob Neyer. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches. New York, NY: Fireside, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2004, 484. His first occurred on September 18, 1897, while pitching for the Cleveland Spiders, in the first game of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds.

3 “Young’s Record: It May be Tied but Never Can be Beaten: A Shutout in Runs and Hits,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, Sunday, September 19, 1897, 8.

4 Game Coverage, Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, Sunday, September 19, 1897, unknown. From SABR web site; Research Resources, Newspaper Scans.

5 “Cy Young’s Great Feat: He Shut Out Cincinnati Without Allowing the Reds a Hit,” Baltimore American, Sunday, September 19, 1897, 10.

6 Young’s first no hitter was the first in the National League (NL) since 1893 when Bill Hawke, then with the Ned Hanlon-led Baltimore Orioles, managed the feat on August 16 against the Washington Senators. The key significance of the Hawke no hitter in 1893 was the fact that it was the first at the then new pitching distance of 60.5 feet which is the same distance used in the game today. Additionally there was another common factor between the Hawke no hitter in 1893 and the Young no hitter in 1897 and that had to do with the fact that Dummy Hoy played at center field, on the losing side, in both games. Hoy was with the Washington Senators in 1893 and with the Cincinnati Reds in 1897.

7 The weather information is from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Sunday, September 19, 1897, 1.

8 “The World of Baseball: The League Race: Games Played Saturday, Sept. 18,” Sporting Life, Volume 30, Number 1, September 25, 1897, 3.

9 Information Concepts Incorporated. The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1969. 2337. Incidentally, for those who aren’t familiar with ICI, David Neft was the man behind ICI and it was the ICI research and resultant data that formed the basis for the Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia of 1969.

10 “Not a Hit: Young’s Great Feat Against the Reds Yesterday,” Cleveland Leader, Sunday, September 19, 1897, page unknown.

11 Cleveland Leader, “Not a Hit.”

12 “Not One Hit Off “Cy” Young,” Cincinnati Enquirer, Sunday, September 19, 1897, 2.

13 Cleveland Leader, “Not a Hit.”

14 “Young’s Record: It May be Tied but Never Can be Beaten: A Shutout in Runs and Hits,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, Sunday, September 19, 1897, 8.

15 Cincinnati Enquirer, “Not One Hit.”

16 Game Coverage, Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, Sunday, September 19, 1897, unknown. From SABR web site; Research Resources, Newspaper Scans.

17 “Cleveland Chatter: Patsy’s Boys Playing in Their Old Form Once More: “Cy” Young’s Great Pitching,” Sporting Life, Volume 30, Number 1, September 25, 1897, 4.

18 Reed Browning. Cy Young: A Baseball Life. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000. 283. (Appendix Two: Cy Young’s Greatest Games, Number 3, September 18, 1897, 222–23.

19 Rich Westcott and Allen Lewis. No-Hitters: The 225 Games, 1893–1999. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2000, 9.

20 Al Kermisch. “From a Researcher’s Notebook,” Baseball Research Journal 28 (Society for American Baseball Research, 1999): 141–43, 142.

21 “Great Pitching: “Cy” Young’s Wonderful Work Against the Quakers: Two Out in the Ninth When the Phillies Made Their First, Last and Only Hit,” Cleveland Leader, Friday, July 24, 1896, 3.

22 “Young’s Record: It is One That Will Probably Stand for a Long Time: One Hit and a Shutout,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, Friday, July 24, 1896, 3.

23 “Shut Out at Cleveland: Delahanty Secures the Only Hit Made Off “Cy” Young,” Philadelphia Record, Friday Morning, July 24, 1896, 11.

24 “The Phillies Shut Out in the First Game at Cleveland,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, Friday, July 24, 1896, page unknown.

25 “Boston May Give $10,000 for Young,” Baltimore Sun, Friday Morning, August 27, 1897, 6.

26 “Baseball: News and Comment,” Sporting Life, Volume 29, Number 3, April 10, 1897, 5.

27 “Base Ball Notes,” Providence Sunday Star, Volume XXIX, Number 151, Sunday morning, May 4, 1884, 8.