Giving Up the Stars and Reaching for the Moon

This article was written by Mark Randall

This article was published in Fall 2014 Baseball Research Journal

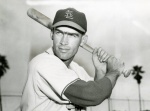

Opening Day, April 13, 1954, should have been one of the best days of Wally Moon’s life. Instead, it was turning out to be one of his worst.1 The heavy-browed, lean-jawed, 24-year-old rookie from Bay, Arkansas, was the starting center fielder for the St. Louis Cardinals. But as he came to bat for the first time in the big leagues, Moon was greeted by a harsh chorus of boos from the hometown fans and chants of “We want Eno! We want Eno!” from “seemingly every corner of the park.”2 Moon had to fill the shoes of longtime Cardinals great Enos Slaughter, who had been traded to the Yankees two days before the start of the season. The trade shocked the city, and disgruntled fans let the Cardinals management and the newcomer know they weren’t too happy. As a young boy growing up in Arkansas, Moon had rooted for the Cardinals and signed with the team in 1950 because of his admiration of Slaughter. Now, he was replacing his favorite player. “I guess there would have been catcalls at anybody who was to take the place of an old favorite like Enos,” Moon said.3

Moon wasn’t even on the roster when the Cardinals started spring training.4 The trade put “team manager Eddie Stanky, who had advocated the trade,” on the spot, but the spotlight glared with even harsher intensity on Moon.5 “All of a sudden they told me that I was going to be on the St. Louis Cardinals roster and I’m going to open in center field Tuesday,” Moon recalled. “This was on a Sunday. I’m shocked, but I’m excited.”6 Moon was given a cool reception the next day during the team parade through downtown St. Louis. All along the parade route, fans carried signs expressing their disapproval of the trade and shouted at the rookie. Riding in an open convertible, Moon couldn’t help but hear the calls directed his way. “Everyone along that parade route was yelling ‘We want Slaughter! We want Slaughter,’” Moon recalled. “There was a huge picture on the front page of the newspapers with Slaughter weeping in a towel. He had been there seventeen years and was an icon and a great player. I loved him as a young man listening to him on the radio. So to replace a legend like that, there was a lot of controversy, a lot of upset people. So I made that parade route through downtown and was not well received.”7

Moon, however, showed the fans that he belonged in the lineup. The rookie outfielder stepped into Slaughter’s shoes, smashing a home run in his first at bat as a major leaguer. After outfielder Rip Repulski flied out to first for the first out of the inning, Moon connected on a 2–0 pitch from the Chicago Cubs’ Paul Minner. The ball went over the roof of the right-field pavilion in Sportsman’s Park, onto Grand Avenue. Only one other Cardinal had debuted with a home run, left-handed hitter Eddie Morgan, who hit one off Lon Warneke of the Cubs in the 1936 home opener. By the time Moon got to second base, the boos had changed to roars of applause. “It was a huge, magnificent home run for me,” Moon wrote in his 2011 autobiography, Moon Shots. “And it took a lot of pressure off.”8 Moon became a hitting sensation from that point on and helped take away some of the sting of losing Slaughter. Moon batted .304 on the season (12th best in the league), banged out 193 hits, clubbed 12 home runs, scored 106 runs (sixth best in the league), led the Cardinals with 18 stolen bases, and was named NL Rookie of the Year. Slaughter, by contrast, started in only 22 games in the outfield and batted only .248 in a limited role for the New York Yankees. He missed over a month of the season after crashing into the outfield wall at Yankee Stadium, fracturing his wrist in three places and was traded the next season to the Kansas City Athletics. (The “Old War Horse” then rebounded to hit .322 for Kansas City and was reacquired by the Yankees for the waiver price on August 25, 1956. Although he was used sparingly over the next four seasons, Slaughter would go on to help the Yankees to win three straight pennants and two World Series between 1956 and 1958.)

Wally Moon almost didn’t get his chance. By the time he arrived in the major leagues in 1954, Moon had already earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from Texas A&M. After four years in the minors and with a newborn child at home, Moon had determined that if he did not make the Cardinals roster in 1954, he would give up baseball and go back to teaching. He had thrived in 1953 under manager Harry Walker with the Cardinals’ Triple-A team in Rochester. Walker was a former National League batting champion whose ten-year career in the majors was spent mostly in the Cardinals outfield, alongside Slaughter and Stan Musial. Walker was being groomed as a big league manager. Moon matured offensively as a Red Wing, batting .307 with 12 home runs and 61 runs batted in. “The baseball gods were smiling on me when they brought Harry Walker into my life,” Moon recalled.9

Impressed by his performance at Rochester, the Cardinals suggested he continue to hone his skills in winter ball. Excited about the possibility, Moon, with his wife and infant son in tow, headed to Maracaibo where he was assigned to Pastora de Occidente in the Venezuela League. The team went on to win the Venezuela League championship and would represent the country in the Caribbean World Series in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The Venezuela club wired the Cardinals to ask if Moon could remain and got permission for him to stay with the team for the World Series. Moon was scheduled to report to the Cardinals minor league camp in DeLand and because of the tournament would be late reporting to spring camp. When the Caribbean World Series was over, Moon wired the Cardinals for instructions. General Manager Dick Meyer gave Moon the option of reporting to either the club’s minor league base in DeLand or St. Petersburg, where the big league club was working out, whichever worked out best for him.10 Moon talked it over with his wife and reached a critical decision. “Just two months in Rochester and the winter in Venezuela made me realize that I was no longer willing to keep dragging my wife and child with me in pursuit of my baseball dream,” Moon wrote in his autobiography. “I believed I had the talent and I wanted the big club to take a look at me and make a decision. I needed an answer one way or the other.”11 Moon took Dick Meyer at his word and decided to head to the Cardinals’ big league camp in St. Petersburg.

The Cardinals held spring training in two stages in those days. They had an early camp about 20 miles from Daytona Beach at DeLand, Florida, for rookies and players they wanted to look at. Then, after two weeks, the team moved to St. Petersburg to start regular spring training. Because of the Caribbean World Series, Moon recalled that “there were only a few days left in the rookie camp and I knew that manager Eddie Stanky already had left camp and wouldn’t even see me.”12 After checking his wife in at the Cardinals headquarters at the Bainbridge Hotel in St. Pete, Moon walked the half dozen blocks to Al Lang Field where the team worked out and introduced himself to the manager. Stanky was angry. “You were supposed to report to Daytona,” Stanky said. “You weren’t supposed to report here.” Moon explained the choice he had been given and told Stanky, “Yeah, but you’re here. They’ve seen me play. They know what I can do. I want you to see me.” Stanky growled a bit, but liked his spirit and told Moon that he could hang around and work out with the Cardinals until they straightened the situation out.13

It was a daring move for the young rookie. “I showed up in St. Petersburg and said to the Cardinals, ‘You promised me a shot. I want to find out if I can play in the big leagues. And I’m not going to sign a minor league contract and go back to Triple-A baseball,” Moon recalled in a 2011 radio interview.14 Stanky asked if Moon had his equipment and said Moon might as well work out since he was there. Two left-handed pitchers, Al Brazle and Royce Lint, were throwing batting practice that day. Moon filled the park with line drives. “I found my groove quickly and I sent frozen ropes to right, center, and left fields,” Moon recalled.15 Stanky called Moon out of the outfield early during that first morning’s workout and sent him to get outfitted with a spring uniform with the number 20. “He made an impression on all concerned,” Stanky said.16

Moon’s timing was perfect; the team was looking to unload its aging star in Slaughter.17 The Cardinals had finished in a tie for third place in 1953—22 games behind the Dodgers—and new club president “Gussie” Busch wanted to build a winner. Anheuser-Busch had bought the team from Fred Saigh, who had become an embarrassment to baseball after he had run afoul of the Internal Revenue Service during the 1952 season. Saigh was hit with a fine and given a fifteen-month jail sentence.18 Busch set out on a long-range program of building the team from the ground up. “The Cardinals are trying to build a young ball club,” Busch said.19 Stanky knew the Cardinals had to be reshaped and that Slaughter had to be replaced if the team was going to be competitive. But until his replacement was found, the club had hoped he had one more good season left in him.20

Slaughter had no idea his days with the Cardinals were about to end. On December 28, Busch signed a contract with Slaughter for the 1954 season. “After the signing he said to me, ‘You’re a credit to the game, and you’ll always be with me,’” Slaughter wrote in his autobiography.21 But going into spring training, Slaughter was about to turn thirty-eight and the “old man” talk was already starting. He had been synonymous with the Cardinals for sixteen years in a career marked by brilliant fielding, clutch hitting, and a reputation for hustle. Slaughter, whose lifetime batting average with St. Louis was .305, was the last member of the colorful Gas House Gang. He had played against the Yankees in the 1942 World Series and also in 1946 when he hit .320 in the seven games against the Red Sox and scored that Series’ most storied run. He had played well in 1953, appearing in 143 games and hitting .291 while driving in 89 runs. Slaughter was excited about the Cardinals’ chances against the Dodgers. Busch had not only bought and renovated Sportsman’s Park, but spent more than $300,000 in money and traded players for three minor leaguers.22 And during spring training, the club gave $75,000 and two minor leaguers to the Yankees for 35-year-old powerhouse right-handed pitcher Vic Raschi. Slaughter saw the trade for Raschi as a big plus, “But I wasn’t aware that the other shoe was about to drop.”23

Slaughter faced competition in the outfield that year in spring training from Joe Frazier, a journeyman who had played in nine games with Cleveland in 1947 and had hit .332 at Oklahoma City, and from Moon, who had hit .307 at Rochester. Slaughter was conscious of the situation, but everyone expected that he would play his usual 140 or 150 games. “Even though both of these outfield prospects displayed potential for power, I wasn’t bothered by the situation,” Slaughter wrote.24 He stopped at Moon’s locker one day and told the young rookie, “Don’t worry. You’re not going to get my job.”25

Meanwhile, Moon drove himself hard. “I gambled on everything,” Moon told Sports Illustrated in 1957. “If I hit a single, I’d go for two. If I had two, I’d go for three. I tried to catch everything I had the slightest chance for in the outfield. I ran every place. Boy, was I tired that spring. I’d get home after practice and I’d fall asleep on the couch. Bettye would wake me up for supper and we’d eat, and I’d fall asleep again. That’s the way it went all spring.”26 Moon went all 45 days of spring training without a contract of any kind. The Cardinals wouldn’t give him a major league contract, and he wouldn’t sign a Triple-A contract. Fortunately, he was in great shape from having played winter ball and was playing well. “I know I was making an impression on Eddie Stanky and his staff,” Moon reflected.27 Stanky said little to Moon, but continued to insert him into the lineup on a regular basis.

Moon took it as a good sign when he earned a spot on the travel squad which was heading to Los Angeles for a weekend series against the Chicago Cubs. “I viewed my presence as a sign the team was beginning to like what it was seeing from me,” Moon wrote.28 As it turned out, Stanky had seen enough. “We’ve got at least an outside chance to win the pennant,” Stanky told reporters. “So if I think Moon can help us more than another outfielder, he’ll stick as one of our 25 players. In other words, I’m not going to worry about whether he’d be better off playing regularly in the minors than infrequently with us. If he can help, he’ll stay.”29 When the team broke camp for its trek north to St. Louis, Moon was invited along for the ride, although the final regular season roster had not yet been determined. A few more cuts would have to be made. Moon still did not know whether he was destined to become a St. Louis Cardinal. Moon approached Dick Meyer about a contract but was told, “We’re not ready to make a commitment yet.” Asked what he should do with his wife and child, Meyer replied, “If I were you, I’d send them home to her mother.”30

The Cardinals played a series of exhibition games with the Chicago White Sox as both teams traveled north. Stanky mostly kept Moon on the bench, using him as a pinch runner or as a late-inning defensive substitute for Slaughter. Moon didn’t know it at the time, but as it turned out, the club was “parading Slaughter on an abbreviated farewell tour during the team’s excursion in cities and towns in Cardinal country.”31 In St. Louis for the team’s weekend pre-season series with the Browns, Slaughter doubled off Bob Turley for the game-winner. It turned out to be his last hit as a Cardinal. Slaughter was not in the line-up for the Sunday game. In the eighth inning, with the Cardinals down 8–1, Stanky informed Slaughter that general manager Dick Meyer wanted to see him. As he changed into street clothes, Slaughter had no idea it would be his last time in a Cardinals uniform. He strolled up to Meyer’s office “completely unprepared for the news I was about to receive.”32

Meyer gave it to him straight. “Eno, all good things must come to an end,” Meyer said. “We’ve traded you to the New York Yankees.”33 Slaughter was shocked. He had always thought he would retire in a Cardinals uniform. Tears gushed from his eyes “like water from a broken pipe.”34

“It cut my heart out,” Slaughter recalled. “I cried like a baby. I couldn’t help it. I’d been a Cardinal since 1935, and I don’t think anybody who’s ever worn a Cardinal uniform was ever more loyal to it than I was, or put out as hard as I did, or gave as much.”35

Slaughter joined Meyer and Stanky for a press conference where Meyer announced that Slaughter had been traded for outfielder Bill Virdon, pitcher Mel Wright, and Emil Tellinger. The Old Warhorse was seated with his hands on his knees, nervously unfolding his handkerchief. “This is the biggest shock of my life,” Slaughter sobbed. “To think that I spent nearly all of my life with this organization and then they trade me after I’ve given them everything I got. I didn’t think it would ever happen to me. I’m not through. And I’ll say this—I’ll be around when a lot of the guys they got now will be gone. But you can tell ’em in New York that I’ll give ’em 100 percent just as I did in the Cardinal organization.”36 Many baseball writers speculated that the Slaughter trade was part of the February 23 deal in which the Yankees had sold Vic Raschi to St. Louis for $75,000, but Meyer and Stanky denied it. Meyer said the Yankees expressed an interest in Slaughter around the time of the Raschi deal but were told he was unavailable until they saw how he would perform in spring training. The deal developed quickly, he said, after the Cardinals left Memphis on their homeward-bound barnstorming trip.

Stanky said the trade had been made to make room for Moon in the outfield. The 24-year-old Moon had been impressive in spring training and Stanky felt he was ready for major league ball. He also did not believe the 38-year-old Slaughter could adapt to a reserve role. “A player like Slaughter just can’t stand sitting on a bench,” Stanky told the press.37 Stanky also pointed out that the club had other rookie outfielders like Joe Frazier and Tom Burgess and “if I had Enos sitting around I know I wouldn’t use them.”38 Meyer and Busch admitted the trade was a gamble, but said they felt it was a sound organizational move because of the opportunity to give the younger Moon a chance to play. “We realize this is a difficult thing from a public relation viewpoint,” Meyer said. “But we’ve got a continuing obligation to have a top contender. We can’t buy a pennant. We have to build a cycle to develop stars. We don’t think we’ve imperiled our chances. But we realize we are taking a risk.” Busch, in a prepared statement, added, “The Cardinals are building a young ball club. We are looking for an organization that will give us strong teams and pennant winners for years to come and we must look to the future. We have several very promising young outfielders with the Cardinals and in our system. They are knocking on the door of the Cardinals right now and we have to make a place for them.”39

Stanky predicted that if Moon lived up to his potential, he would soon make the fans forget about Slaughter. “Moon has some flaws like the rest of us,” Stanky said. “But he is the best prospect I’ve seen here in three years outside of [Rip] Repulski. If he hits or makes the great plays, he’ll have his own following too.”40

Meanwhile news of the trade had not yet filtered down to the players. Moon had taken his time leaving the field after the final exhibition game, fearing it might be his last time wearing a baseball uniform. As he sat in the clubhouse at Sportsman’s Park, he slowly undressed and clung tightly to his No. 20 Cardinals jersey before finally tossing it in a pile of soiled uniforms. He had come so close. He had played hard in spring training and played well, but none of the signs looked good. He had received less and less playing time as the season opener drew close. “With the regular season opener just two days away, all I’d gotten from team management regarding my future with the club was a half-hearted ‘we’ll see,’” Moon recalled.41

Then one of the locker room attendants came up to him and told him, “Stanky wants to see you.” A few teammates looked at him as he got up to walk to the manager’s office. He felt like “a dead man walking to his baseball doom.”42 Moon was sure the manager was going to tell him that he didn’t make the team. Moon and his wife had already discussed the options if the Cardinals chose to send him back to the minor leagues. He had a wife and a young son to support which was difficult on a minor league salary of only $300 a month. But with a college diploma and a master’s degree, they were prepared to return to Arkansas where he could teach and coach. “Bettye was in full agreement,” Moon recalled. “If I didn’t make the Cardinals opening day roster I’d give up the dream and devote myself full time to a career in education.”43 Fearing the worst, Moon closed his eyes, took a deep breath, and walked into Stanky’s office.

“Well,” Stanky said. “You’ve made the team.” “Thanks Eddie,” Moon replied. “I won’t let you down.”44 Stanky had one more bit of news. Not only had he made the team, the club had traded Enos Slaughter and he would be taking his place in right field. “That’s it,” Stanky said. “Congratulations.” Walking back to the locker room Moon was congratulated by several of his teammates. But there was a somber silence that hung in the atmosphere as the club digested the news that Slaughter had been traded.

One veteran quipped, “It looks like the manager is giving up the stars and reaching for the moon.”45 Stan Musial saw Slaughter in the parking lot and the two men looked at each other and cried. “We had spent a lot of years together in the heart of the Cardinals lineup and it was really sad for both of us to know that our one-two punch had been broken up,” Slaughter recalled.46

Cardinals fans were used to management trading away good players. General Managers Dick Meyer, Frank “Trader” Lane, and Bing Devine were forever trying to pull off the one deal they thought would make a difference. But as Cardinal historian Bob Rains wrote, “Unfortunately, at least until the end of the decade, almost every deal the Cardinals had attempted turned out to be a mistake.”47 In 1951, the Cardinals traded Joe Garagiola, Howie Pollet, and Ted Wilks and two other players to Pittsburgh for Wally Westlake and Cliff Chambers. The trade backfired as Garagiola had several good seasons for the Pirates, while neither Westlake nor Chambers turned out to be effective for the Cardinals.48 But the trade that produced the biggest fan reaction was Slaughter’s. Furious callers flooded the Cardinals’ switchboard, many threatening to cancel their season tickets. Some cried as much as Slaughter. Busch had to take the phone off the hook at his Grant’s Farm estate.49

Stanky also had to endure the barbs. “I’ve been a so-and-so before and I guess I am a bigger so-and-so now,” Stanky said. “But I can take it.”50 Fan reaction was overwhelmingly negative. “I’m surprised and I definitely think it will hurt the Cardinals,” said a bartender. “I think it is a very good move for the Yankees.” A salesman said the club was “crazy.” One taxi driver called the Cardinals “stupid” and another said “that’s a dirty deal.” The second cab driver went further: “Since they got rid of Slaughter they just might as well get rid of Stan Musial and the rest of the good hitters and give up baseball.” One of the briefest comments came from a cashier who said, “It’s lousy.”51 Bob Burnes, a columnist for the Globe-Democrat, wrote that while the Cardinals could find reasons to justify the trade, none of them would satisfy the fans. “Enos Slaughter was more than a ballplayer, as any Cardinals fan could tell you,” Burnes wrote. “He was an institution—not only among the fans, but among the players as well. Enos was the ballplayer’s ballplayer—he played the game the way it should be played.”52

The day after the trade, Moon made his first official appearance as a Cardinal, in the aforementioned parade, during which the fans expressed their displeasure.53 “As the motorcade revved to a start, it was now official before God and thousands of Cardinals fans. I was the player designated to fill the spiked shoes of the legendary Enos Slaughter,” Moon recalled.54

During the Cardinals’ final pre-season workout Moon seemed “nervous, even a bit embarrassed as he vigorously chewed gum during an interview at the batting cage.55 Moon told reporters that although he’d had offers from sixteen major league clubs—several for the $6,000 that would have made him a Bonus Baby—he chose to sign with the Cardinals “because they were my favorite team and Slaughter my favorite player. I admired the way he hustled and how hard he played.” When asked about the mental pressure of replacing a popular player like Slaughter, Moon replied: “It’s an honor to replace a player like Slaughter. Yes, I was surprised—surprised that he was traded and surprised I got the chance—but I’m happy. No, I don’t think I’ll be nervous in the game.”56

It wasn’t until Monday, the day before Opening Day that Moon was called into the front office. “I guess you better sign a contract,” he was told. “I guess so,” Moon agreed. “I would have signed anything after all those weeks.”57 Things weren’t any better the next day for Moon as the Cardinals opened the season against the Chicago Cubs. With a crowd of 17,027 on hand, it was the first afternoon opening game at home for the Cardinals since 1950. Prior to the game as he took batting practice or warmed up on the field, Moon could hear the hecklers in the stands. “For many in attendance that day I was already the team villain, and I hadn’t said or done a thing.”58 Moon was scheduled to hit second in the lineup that day. Minner was a 6-foot-5 lefty. As Moon knelt in the on-deck circle he felt like the most despised player in baseball. But, he said over and over to himself, “‘You can’t let this bother you. This is what you’ve been waiting for. This is the one chance you have been asking for.’ I pep-talked myself.”59

As soon as Moon stepped into the batter’s box, chants of “We want Eno! We want Eno!” echoed throughout the ballpark. Minner’s first pitch, a curveball, missed the outside of the plate for ball one. His second pitch, an off-speed pitch, came in for ball two. “Take the bat off your shoulder,” Moon heard someone shout.60 With a 2–0 count, Moon expected the fastball and he sent it over the roof of the right field pavilion to give the Cardinals a 1–0 lead. The chorus of boos quickly turned into cheers. “It’s still my biggest thrill in baseball,” Moon recalled. “All I remember about the homer is coming back to the bench after I hit it and seeing Gussie Busch in his box near the dugout, jumping up and down.”61 The game was also notable because it marked the debut of twenty-three year-old first baseman Tom Alston, who was the Cardinals’ first black player.62 The Cubs got 16 hits however, and won the game 13–4. It was the Cardinals’ worst home opener in years. But as Moon recalled, it wasn’t a complete loss for him because, when he didn’t wilt under the pressure, “from that afternoon forward St. Louis fans held me in much higher esteem.”63

As previously mentioned, Moon became only the second Cardinal to hit a home run on his first major league trip to the plate. Eddie Morgan accomplished the feat on April 14, 1936, in the season opener against the Cubs at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis.64

Moon continued to hit the ball well the rest of the season and did his best to make St. Louis fans forget Enos Slaughter. On April 23, Moon collected five hits in a 7–5 loss in 11 innings at home to the Milwaukee Braves, in a game that saw Hank Aaron hit his first major league home run. Moon had another five-hit performance against Pittsburgh on May 12. On May 25, Moon stole four bases against the Cubs, coming within one of what was then believed in the press to be the National League record of five. (The actual NL record was seven, albeit with a different definition of stolen base. Under the definition in effect in 1954, the record was actually four.) By midseason Moon’s batting average was hovering around .325 and sportswriters were already talking about him as a sure candidate for Rookie of the Year.

Musial was impressed: “I’ve never seen a rookie who is less concerned when he has two strikes on him. He always knows he had a third coming.”65 Stanky added that “he controls the strike zone better than any first year player I’ve ever seen. He’s as familiar with that strike zone as he is with the palm of his hand.”66 Moon hit well over .300 most of his rookie season and was in the thick of the race for the NL batting championship, but fell into a slump during the final two months of the season that dropped his average some 35 points. He hit only .239 in August and .227 for the month of September. “One reason is that I wasn’t beating out those infield hits,” Moon said. “I had played in winter ball and I was tiring badly at the end of the season.”67 Moon still finished with a .304 average and ended the year the same way he started it—with a home run. In the 11th inning of a game in Milwaukee, Moon belted a pitch from Ernie Johnson 400 feet into the center-field bullpen for a two-run home run, handing the Cardinals a 2–0 win over the Braves.

Despite topping the league in just about every offensive category, the Cardinals finished 72–82, sixth in the league. But as Time pointed out in its August 23, 1954, edition, the good news for the Cardinals was that Wally Moon had made the grade. “He is filling in so well for Slaughter that the fans have almost forgiven the Cardinal management for selling Old Enos to the Yankees. Unless he suddenly picks up the habit of catching fly balls on his head, Wallace Wade Moon is a sure bet to be selected National League Rookie of the Year.”68 Moon got 17 of 24 votes from a committee of sportswriters, beating out future Hall of Famers Ernie Banks and Hank Aaron for Rookie of the Year honors in the National League. The writers noted that Moon did a “whale of a job all year,” collecting 193 hits, scoring 106 runs, and batting a respectable .304. “The lean, serious-minded outfielder with a masters degree from Texas A&M proved a triple threat man with the Cardinals. Besides his outstanding hitting and fielding, he also proved adept on the bases, stealing 18 sacks.”69 For Moon, it was a dream come true. “All of my life I knew I would make it someday,” Moon said. “I had faith in myself. But I never would have foreseen it happening the way it did.”70

Moon followed his sensational rookie year with four more productive seasons for the Cardinals, batting .295 with 19 home runs and 76 RBIs in 1955, .298 with 16 home runs and 68 RBIs in 1956, and .295 with 24 home runs and 73 RBIs in 1957, but slumped in 1958, playing in only 108 games and batting only .238 with 7 home runs and 38 RBIs—all career lows. He had injured his left elbow in May when he leaped for a fly ball off the bat of San Francisco’s Orlando Cepeda and collided with the unpadded concrete wall in left-center field, and then with teammate Joe Cunningham, who fell on top of him.

After his disappointing 1958, the Cardinals traded Moon, along with pitcher Phil Paine, to the Dodgers for outfielder Gino Cimoli. The right-handed hitting Cimoli wasn’t much better that year. Cimoli’s batting average had dropped from .293 in 1957 to .246 in 109 games and he was in and out of the lineup all year long. Moon was upset and bitter about the news. Not only did he hear about the trade first from the Dodgers, but his pride was hurt when he found out it wasn’t a straight-up trade. “The trade rocked me to the core,” Moon wrote in his autobiography. “My employer, my favorite team since childhood, had given up on me for someone I considered a lesser talent.”71

“The Dodgers made a helluva deal,” Moon told Dodgers GM Buzzie Bavasi. “A lot better one than the Cardinals made.”72 The Cardinals, however, felt they were getting a defensive upgrade from Moon and that Cimoli’s “ability to hit to right center will be useful at Busch Stadium.”73 Cards manager Solly Hemus told reporters that while Cimoli probably wasn’t the .293 hitter of 1957, he was better than the .246 batter of 1958.74 Cimoli was “an excellent outfielder with an outstanding throwing arm.” Sportswriter Bob Broeg wrote that “we wish Wally well, but a reporter who travels with the Redbirds these last several seasons would not be hypocritical if he didn’t acknowledge disappointment in the athlete from Texas.”75 Broeg continued, “Even though he fell off to .238 last season, Moon is basically a good hitter, a man of power at the plate when he connects, but he disappointed consistently afield, both fly chasing and throwing. He seemed so satisfied with his inadequacies that his lean and hungry look appears merely an unfortunate illusion.” Dodgers Vice-President Fresco Thompson saw it differently, commenting, “Moon’s got 80 percent ability and gives you 100 percent. Cimoli’s got 90 percent ability and gives 75. In the end, we’re ahead with Moon.”76

Thompson was right: Moon would turn out to be a great pickup by the Dodgers. He rebounded to hit .302 with 19 home runs and became a fan favorite by hitting “Moon shots” over the Coliseum’s left field screen. He was a critical part of the Dodgers’ 1959 World Series championship team. He was initially concerned about playing in the Dodgers’ temporary home—the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum where the right field foul pole was 440 feet away and where fly balls went to die. He had little success there in 1958, going 2-for-22. But thanks to advice from former teammate Stan Musial, Moon learned how hit the ball the opposite way over the 42-foot-high left field fence, which was only 251 feet away. “He set me down and told me I could use that screen to my advantage,” Moon recalled. “I was just going to have to put more emphasis on hitting to left. I knew pitchers in the Coliseum threw inside to left-handed hitters hoping to get them to hit to right or center where they couldn’t get the ball out very often. What I did was get my hands inside of the ball, leading the bat through and extending it for power. I tried to hit the bottom half of the ball to produce high fly balls.”77

Of the 19 home runs Moon hit that year, 14 were at the Coliseum and nine of them were over the screen. At one point, Moon hit safely in 17 straight games and showed some of the old spark and daring on the basepaths, stealing 15 bases. “He is just the type of player we thought we were getting,” Bavasi said.78 Moon was named to play in both All-Star Games and finished fourth in the National League’s Most Valuable Player balloting. The Los Angeles writers voted Moon the Most Valuable Player of the 1959 World Champion Dodgers, and he finished second in the Associated Press Comeback Player of the Year to Philadelphia’s Gene Conley. Moon was also the choice of United Press International for the No. 1 Comeback Player of the Year in the National League. “Certainly in a year in which so many Dodgers stood out at various stages of the campaign, Moon must be singled out,” Bavasi said. “No player was more consistent throughout the campaign and no one man was more a team player than Wally.”79

Although he would go on to be a part of three World Series winning teams, Moon always considered that first storybook home run to be the greatest thrill of his baseball career. Speaking to the Craighead County Historical Society in 2012, Moon reflected, “Everyone from Northeast Arkansas dreamed of playing for the Cardinals. And there I was in the lineup and hitting a home run. It is hard to beat anything like that.”80

MARK RANDALL has been an award-winning journalist for the past 15 years. He has covered a number of beats for newspapers in Massachusetts, New Mexico, Florida, Utah, Alabama, Arizona and Arkansas. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history from Northeastern University, a master’s degree in broadcast journalism from Syracuse University, and a second master’s degree in history from Arkansas State University, where had has also taught undergraduate history courses.

Notes

1. Moon, Wally with Tim Gregg. Moon Shots: Reflections on a Baseball Life. San Antonio, TX: Moon Publishing, 2010. 1.

2. Ibid., 1.

3. Gross, Milton. “Rookie of the Year.” Sport, January 1955, 49.

4. “Wally Moon Senior League Rookie of Year.” St. Joseph Gazette, December 20, 1954.

5. Gross, 70.

6. “Wally’s Reflections: Wally Moon’s First Big League Home Run.” www.wallymoon.com/ahomerun.htm.

7. Bock, Gabe. “Aggie Flashback: Reflections from A&M Legend Wally Moon.” September 20, 2011. http://v4.texags.com/Stories/2978.

8. Moon, vii.

9. Ibid., 65.

10. Creamer, Richard. “Hope of St. Louis.” Sports Illustrated, April 22, 1957. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1132365/index.htm.

11. Moon, 74.

12. Fraley, Oscar. “Moon Not Worried by Sophomore Jinx.” United Press, February 5, 1955.

13. Creamer, op. cit.

14. Bock http://v4.texags.com/Stories/2978.

15. Moon, 75.

16. Gross, 49.

17. Moon, 115.

18. Honig, Donald. The St. Louis Cardinals: An Illustrated History. New York: Prentice Hall, 1991. 142.

19. Ibid., 142.

20. Gross, 78.

21. Slaughter, Enos with Kevin Reid. Country Hardball: The Autobiography of Enos ‘Country’ Slaughter. Greensboro: Tudo Publishers Inc., 1991, 153.

22. Musial, Stan as told to Bob Broeg. The Man Stan Musial…Then and Now, St. Louis: The Bethany Press, 1977. 151.

23. Slaughter, 153.

24. Ibid., 153.

25. Creamer op.cit..

26. Ibid.

27. Bock op.cit..

28. Moon, 78.

29. “Stanky Is Cautious in Trimming Squad.” Associated Press, March 24, 1954.

30. Moon, 81.

31. Ibid., 82.

32. Slaughter, 154.

33. Ibid., 154.

34. Ibid., 154.

35. Honig, 144.

36. “Yanks Sought Enos in Rashi Deal.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 12, 1954.

37. Broeg, Bob. “Trade of Slaughter Puts Rookie Moon and Cardinal Office on Spot.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 12, 1954.

38. “Cards Deal War Horse to Yanks. Slaughter, Mates, Fans Shocked.” Associated Press, April 12, 1954.

39. Ibid.

40. “Yanks Sought Enos in Rashi Deal.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 12, 1954.

41. Moon, 2.

42. Ibid., 2.

43. Ibid., 3.

44. Ibid., 4.

45. Gross, 49.

46. Slaughter, 155.

47. Rains, Bob. The St. Louis Cardinals: The 100th Anniversary History. New York: St. Martins Press, 1992. 134.

48. Ibid., 134.

49. Ibid., 135.

50. “Yanks Sought Enos In Rashi Deal.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 12, 1954.

51. “Cards Deal War Horse to Yanks. Slaughter, Mates, Fans Shocked.” Associated Press, April 12, 1954.

52. Rains, 135.

53. Moon, 5.

54. Ibid., 6.

55. Broeg, Bob. “Wally Moon Replacing His Idol; Says Admiration for Slaughter Inspired Signing with Redbirds.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 13, 1954.

56. Ibid.

57. Creamer op.cit.

58. Moon, 1.

59. Gross, 49.

60. Moon, 8.

61. Creamer op.cit.

62. Snyder, John. Cardinals Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day with the St. Louis Cardinals. Covington, KY: Clerisy Press, 2010. 405.

63. Moon, 11.

64. Tomasik, Mark. “Oscar Taveras, Eddie Morgan: Flashy Start to Cards careers.” June 18, 2014. http://retrosimba.com/2014/06/oscar-taveras-edie-morgan-flashy-starts-to-card-career. With the Cards trailing 12–3, Manager Franke Frisch sent in Morgan in the seventh as a pinch-hitter for reliever Bill McGee. The left-handed rookie connected on the first pitch he saw from Lon Warneke, sending the ball over the right-field wall for a two-run home run.

65. Gross, 79.

66. Ibid., 79.

67. Fraley, Oscar. “Moon not Worried by Sophomore Jinx.” United Press, February 5, 1955.

68. Moon, 99.

69. “Wally Moon Senior League Rookie of the Year.” St. Joseph Gazette, December 20, 1954.

70. Gross., 79.

71. Moon, 146.

72. “Wally Moon Now Rated Top Prophet with Dodgers.” Associated Press, June 22, 1959.

73. Broeg, Bob. “Cards Trade Moon for Cimoli.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 4, 1958.

74. Broeg, Bob. “Moon Gone, Cards May Use Cimoli as Bait for Moryn.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 5, 1958.

75. Ibid

76. Moon, 146.

77. Springer, Steve. “Dodger’s Moon Found Success in Coliseum.” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2008.

78. “Wally Moon Now Rated Top Prophet with Dodgers.” Associated Press, June 22, 1959.

79. “Moon Voted No. 1 Comeback in National Loop.” United Press International, October 22, 1959.

80. “Former Cardinal Moon Recalls Playing Days.” Jonesboro Sun, July 24, 2012.