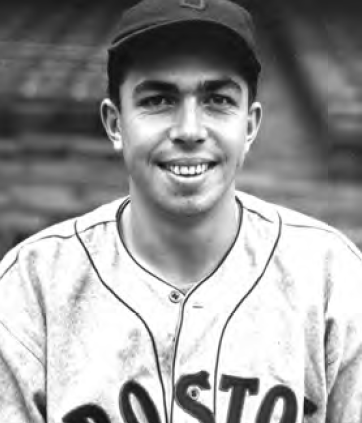

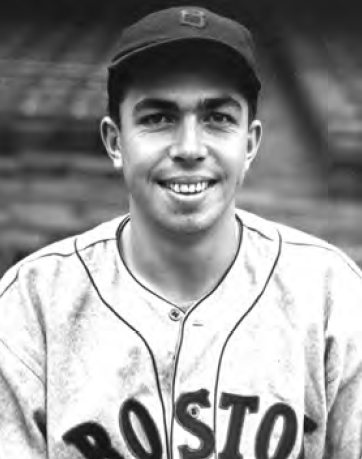

Mel Almada: The First Hispanic to Homer at Several Historic American League Stadia

This article was written by Lou Hernandez

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

The Almada family of Sinaloa, Mexico sought refuge from the civil unrest of the Mexican Revolution, emigrating to the United States in 1914. The Southern California city of Los Angeles offered Baldomero Almada a safe place for his family and a ranking position in the Mexican consulate.

“My father always wanted us children to have an American education,” said Mel Almada, Baldomero’s younger son, early in his baseball career. “So when the opportunity came along for him to become Mexican consul at Los Angeles, he turned over most of his property to relatives and moved us all to this country. I was then only a year and one-half-old, so, you see, I am very much an American.”1

Prior to moving to the U.S., the Almadas had relocated to Sinaloa’s bordering northern state of Sonora.2 There, in Huatabampo, Almada’s second son, Baldomero Melo, was born on February 7, 1913, the second and last male addition to a family unit that also included six girls.

A short time later, Almada, Sr. was offered a chance at the governorship of Baja California, which he turned down. Rather than challenge the sitting governor of the region for the seat (which the incumbent governor did not want to relinquish), Almada chose to avoid a political power struggle and instead redirected his family to Los Angeles.

In a profile appearing in The Sporting News in 1935, Melo “Mel” Almada’s first full major league season, the outfielder revealed the subplot: “My father sort of looked into the situation because it would have been a high distinction to become governor of that state. But it didn’t take him long to make a decision. He found out that the governor [who] the president had sought to remove had a large, well-equipped army, while my dad’s army consisted of my mother and eight children. Lord only knows what would have happened to all of us had we moved to Lower California.”3

It is safe to say the course of major league and Hispanic baseball history would have been altered had Baldomero Almada been more politically inclined.

Mel Almada was thus afforded the opportunity to run the educational gamut of the Los Angeles public school system, attending Jefferson Grammar School, John Adams Junior High, and Los Angeles High School, where Mel suited up for football, baseball, and track and field. A gifted halfback and pitcher for the Romans, he also set a school long jump record at 23 feet, 4¾ inches. He was a natural athlete, as had been his older brother, José Luis (known as Lou).

In the late 1920s, Lou Almada joined the Pacific Coast League’s Seattle Indians and became an everyday outfielder. In 1932, Lou arranged a tryout for his kid brother. At 19, Mel was such a standout that he ended up taking his brother’s starting job. Lou Almada found other employment with the San Francisco Missions, and the brothers subsequently played as friendly rivals for nearly two seasons.

Mel, who had played only semi-professional baseball before 1932, had a .311 batting average in his first season with the Indians then followed it up with 204 hits and a .323 mark in 1933. His hitting, and possibly an advanced scouting report, caught the attention of Eddie Collins, first-year Boston Red Sox general manager during a 1933 summer visit to the west coast. Collins had been hired by Tom Yawkey, the 30-year-old multimillionaire who had bought the Red Sox that February.

Collins purchased Mel Almada and two other players, with the agreement that Almada could finish the season with Seattle then join the Red Sox.

After just two seasons of professional baseball, the 20-year-old was the first Mexican-born player in the major leagues. His first day on the big league scene came at Fenway Park, September 8, 1933, against the Detroit Tigers. Wearing uniform number 21, Almada played center field in both ends of a doubleheader, recording four putouts. Mel had a hit in each game and scored his first major league run in the opener. His first major league hit came off Tommy Bridges. The Red Sox, however, dropped both games by identical 4–3 scores.

Some two weeks later, on September 23, Almada connected against the Yankees’ Herb Pennock for his first home run. As a fifth-inning substitute, Almada homered in the same inning, and scored two other runs in a 16–12 loss to the Bombers at Fenway Park. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig also socked home runs. Almada’s long ball was the first home run hit by a Mexican player in the majors and the first by a Hispanic player at Fenway Park.

Almada also visited Philadelphia and New York that September. In his only game in the City of Skyscrapers, Mel collected three hits in three official at-bats at Yankee Stadium, October 1, 1933. Pitching for the Yankees, in the season finale for both teams, was 38-year-old Babe Ruth, who surrendered 12 hits and three walks (two to Almada) in a 6–5 complete game win.

Almada also visited Philadelphia and New York that September. In his only game in the City of Skyscrapers, Mel collected three hits in three official at-bats at Yankee Stadium, October 1, 1933. Pitching for the Yankees, in the season finale for both teams, was 38-year-old Babe Ruth, who surrendered 12 hits and three walks (two to Almada) in a 6–5 complete game win.

The following season, 1934, Mel starred for Boston’s Kansas City affiliate. He had a .328 batting average in 135 games and topped the circuit in stolen bases with 29. In September, the Red Sox called him up and got him into 23 more games.

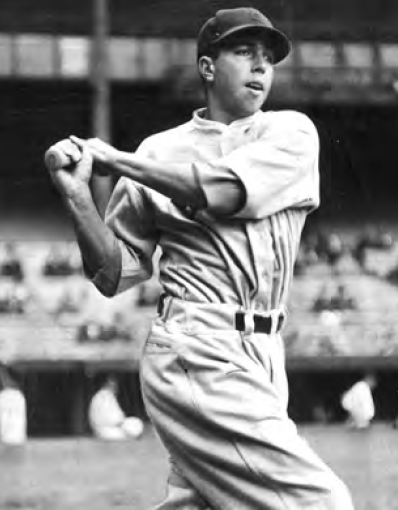

The following spring, at age 22, Almada became Boston’s regular center fielder. Speed was Almada’s greatest asset, and he used it in the field and on the bases. “Almada is as fast as the desert wind that blows across his native Sonora,” read one examining report on the Red Sox rookie. “His arm is geared for long range throwing and he gets the ball away quickly…Almada, a left-handed batsman and thrower, is not a distance hitter, but [manager Joe] Cronin believes his defensive skills will more than make up for his lack of power.” 4

In his first year as a starter, Almada batted .290 in 607 at-bats and stole 20 bases (third best in the league). He spent most of his time in center but also played four games at first base. At the plate, he choked up on the bat, a common hitter’s practice in those days. He struck out only 34 times in 1935. As a major leaguer, Almada struck out only once every 16.5 at-bats, a terrific ratio.

In 1936, the 6 foot, 170-pound outfielder slumped at bat, falling to a .253 batting average, and played in fewer than 100 games . Boston was forced to move first baseman slugger Jimmie Foxx into the outfield for a time in an attempt to rev up their offense. Almada’s on-base and slugging averages dipped to .305 and .338, respectively, compared to the .350 OB and .379 SLG averages of a year earlier.

Late in spring training 1937, Almada was beaned by Cincinnati Reds pitcher Whitey Moore. “Mel Almada, youthful Red Sox outfielder, suffered a concussion today when hit on the head by a pitched ball in an exhibition game with the Cincinnati Reds. The ball struck just behind Almada’s right ear with a crack that could be heard all over the ball park.” 5 Mel was not seriously hurt, although he was kept two days in a local hospital.

He was ready for Opening Day a week later. He filled in at first base for the first four games of the 1937 season, while Jimmie Foxx recuperated from sinus troubles. Upon Foxx’s return, Almada remained in the lineup and was off to a good start, with a .351 batting average in his first nine games, when the Red Sox paid their first visit of the year to Chicago. The White Sox hosted the Red Sox for a two-game set beginning Friday, May 7.

The White Sox’ home was in its 28th year. A double-decked grandstand enclosed nearly the entire playing field of the grand structure at this time. Seating capacity was 52,000.6 The foul line distances were 362 feet in both left and right. Dead center was a cavernous 450 feet from home plate. 7

Boston, with an early-season 6–3 record, jockeyed with the Detroit Tigers and New York Yankees for the top spot in the AL standings. The home team brought up the rear of the eight-team circuit at just 3–8. The Red Sox won the opener, 5–3, behind Lefty Grove.

The next day, White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes selected right-hander Bill Dietrich to counter the Red Sox’ Wes Ferrell on the mound. Ferrell, a renowned hitting pitcher, singled his first time up in the third inning, with one out. Leadoff hitter Almada followed with a home run. The two-run blast was the first scoring of the game and the first home run hit by a Hispanic player at Charlie Comiskey’s “Baseball Palace of the World.”

Dietrich had the last laugh on Almada and the Red Sox, however, pitching five innings to earn a 6–5 victory.

A month later, on June 11, the Red Sox dealt Almada to the Washington Nationals. The change of scenery brought handsome returns for the Mexican outfielder. His batting average in the .230s when he was traded, Almada stepped up with the Nationals and had a .309 batting average in 100 games. Almada credited Nationals manager Bucky Harris with helping him improve his hitting. “ Bucky told me I was a natural-born hitter,” said the outfielder. “And that I could go to town if I used a heavier bat—thirty-five ounce instead of thirty-three—and change my stance and wait for the good ones.” 8

A year after that, June 15, 1938, Washington exchanged the Almada for St. Louis Browns outfielder Sam West. With the Browns in 1938, Almada put together a 29-game hitting streak, as well as a most remarkable string of hitting in 54 of 56 games, from June 21 to August 19. The 29-game hitting streak was the third longest by a Hispanic major league player in the 20th century; Rico Carty hit in 31 consecutive in 1970 and Benito Santiago hit in 34 straight in 1987.

Almada concluded his seven-year big league career with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1939 at only 26 years of age. In all, he hit .284 and socked 15 home runs, five of which were the first home runs hit in those stadia by a Latin American big leaguer. He played the 1940 season for Triple-A Sacramento and managed for part of the 1941 season in the Mexican League.

He served in the U.S. Army in 1944 and 1945, and in the next decade managed in the Mexican League and Mexican Pacific Coast League.

Why did the promising Almada’s career end so soon? He had trouble following up on his early successes at the plate. Some attributed this to being shy of inside pitches; certainly he did not have the power to succeed as an everyday outfielder on a contending team. As a speed and on-base threat, he was simply in the wrong era for his style of play.

Whatever the cause of his early exit, Almada soon went into the fruit distribution business with his brother Lou and enjoyed financial success. Baldomero Melo Almada lived a good life, passing away at the age of 75 on August 13, 1988, from a heart ailment in the rural town of Caborca, in his native Sonora.

In 1971, Almada was part of a third class of honorees enshrined into the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame. Two years later, the organization held the grand opening of the Hall of Fame museum building in Monterrey, Mexico.

The guest speaker at the March 10 event was Bowie Kuhn, the 47-year-old, well-dressed, bespectacled Commissioner of Major League Baseball. He said that day, with some prescience: “I can see in the decades ahead enormous growth of baseball internationally. Today over 60 countries are participating in organized amateur and professional baseball. I can see the day when heroes of your Mexican diamonds will be heroes all over the world.

“ I can remember when, as a 10-year-old boy in Washington D.C., I went out to see my first baseball hero, Mel Almada,” Kuhn added. “It is a big thrill for me today to see my boyhood hero enshrined in your Mexican Hall of Fame.” 9

LOU HERNANDEZ is the author of three baseball histories. He resides in South Florida and roots for the Marlins.

Table 1: First Latin American player to homer in historic AL ballparks

| Ballpark | City | Player | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Stadium | Cleveland | Bobby Estalella | 10/1/1944 |

| Comiskey Park | Chicago | Mel Almada | 5/8/1937 |

| Fenway Park | Boston | Mel Almada | 9/23/1933 |

| Griffith Stadium | Washington | Jack Calvo | 6/5/1913 |

| League Park | Cleveland | Mel Almada | 5/20/1938 |

| Tiger Stadium | Detroit | Mel Almada | 8/21/1935 |

| Shibe Park | Philadelphia | Bobby Estalella | 9/29/1935 |

| Yankee Stadium | New York | Mel Almada | 6/2/1935 |

Sources

Baseball Almanac

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet

Notes

1 Dick Farrington. “Mexican Revolution Gave Mel Almada to the Diamond.” The Sporting News, September 5, 1935.

2 The patriarchal Almada was a descendant of affluent Spanish settlers who helped establish one of the oldest cities in Mexico. The privileged-background homesteaders designed their town with cobblestone streets and lavished upon themselves grand estate houses and erected a great fortress to serve as protection from the indigenous tribes of the region. The fortress, built in 1610, became symbolic namesake of the town, called “El Fuerte.” There, ten generations later, Baldomero Almada started his family. His eldest son, José Luis, was born in El Fuerte, Mexico on September, 7, 1907.

3 Dick Farrington. “Mexican Revolution Gave Mel Almada to the Diamond.” The Sporting News, September 5, 1935.

4 “Cronin Considers Almada Class of 1935 Rookies.” Mount Carmel Item, May 15 1935.

5 “Melo Almada Struck in Head by a Wild Pitch.” The Los Angeles Times, April 14, 1937.

6 Ballparksofbaseball.com.

7 Curt Smith. Storied Stadiums. Foreword by Bob Costas. Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York, New York 2001.

8 Cuddy, Jack. “Melo Almada Clicks Since Traded to Washington.” The Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1937.

9 Ray Gillespie, “Mexico Honors 22 Immortals at Shrine Dedication.” The Sporting News, March 24, 1973.