Lizzie Murphy: An All-Star at Fenway Park

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

To date, there has only been one woman who played baseball with a team of major leaguers in a big-league ballpark. Her name was Mary Elizabeth Murphy and she played for a team of “all-stars” against the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park. Lizzie Murphy’s team beat the Red Sox, 3-2.1

The year was 1922, and the date August 14. The occasion was Tom McCarthy Day—an exhibition game played at Fenway Park. The game was scheduled to benefit ailing but very popular former ballplayer Tommy McCarthy. The Boston Globe called him “one of the greatest outfielders in the game, and who for many years has been close to the hearts of the Boston fans.”2 As it happens, McCarthy died just a couple of weeks before the benefit. Babe Ruth, who had committed to play for the All-Star team, had an operation to remove an abscess from his left leg just a couple of days beforehand; his leg had become infected after a rough slide on the basepaths. Otherwise, Ruth would have played on the same team as Lizzie Murphy. The benefit proceeded nonetheless, repurposed to create a fund to help McCarthy’s daughters. Widely admired among his fellow players, McCarthy was an early Hall of Fame inductee, enshrined in 1946.

Murphy was herself pretty well known in New England at the time. This was an era where women were making great strides in a number of areas. It was in August just two years earlier, in 1920, when the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, granting women the right to vote. Women were active in sports, and newspapers of the day often featured sports page headlines regarding women’s tennis, swimming, and other sports. Murphy was a novelty, for sure, and a gate attraction. She was also a very good baseball player. A Rhode Island native, she’d played with a number of teams for some years, including the Providence Independents. In 1918, she signed with semipro team owner Ed Carr of Boston, who announced on her signing, “No ball is too hard for her to scoop out of the dirt, and when it comes to batting, she packs a mean wagon tongue.”3 With Carr’s All-Stars, she played a hundred games a summer, reports Barbara Gregorich in her book Women At Play.4 Murphy played in games throughout all New England and the eastern provinces of Canada. She had a 17-year career and became known as the “Queen of Baseball.”

At Fenway Park, though, it was to be Queen for a day.

Before taking a look at this game, let us learn a bit more about Murphy’s background.

Mary Elizabeth Murphy was born on April 13, 1894, in Warren, Rhode Island, a town on a peninsula on the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay that had a population of 6,585 in 1910. She was the fourth of seven children born to John E. Murphy and Mary Murphy.5 John was a native of Massachusetts, born to two parents both listed as natives of England. Mary had come to the United States, a native of Quebec, born to two French-Canadian parents. We believe her to be the Marie Garand who lived in Warren at the time of the 1880 Census and worked in a cotton mill; her surname was presented as “Garant” in the obituary for her famous daughter.6 Lizzie was bilingual.7

Mary Elizabeth (“Lizzie”) Murphy first appears in the 1900 United States Census, living with the family in Attleboro, Massachusetts, where her father was employed as an overseer in a cotton mill. Her older sister Sarah, 16, worked as a mill spinner. The household also had a boarder from French Canada, Malvina Ledoux, a mill spooler. John Murphy was said to have also been “known as a long distance runner.”8

By 1910, John and the family were back in Warren, and he was listed as a store keeper, running a confectionery. All six children in the family were born in Rhode Island. The eldest son, Henry, 20, worked as a baker. Eva, a year older than Henry, was a mill spinner. It is unclear whether Lizzie was also working as a spinner in the mill at age 16. That was written next to her name on the Census form, but then crossed out and written in again next to her 12-year-old sister Lena. A 1913 article in the Providence Journal said that Lizzie was “employed in the Parker Mill in East Warren as a ring spinner.”9 In researching Murphy’s background, Debra Shattuck found a 1913-14 edition of The Bristol, Warren and Barrington Rhode Island Directory, which listed Murphy’s occupation as “ball player.”10

Lizzie had completed the fifth grade; that was the extent of her formal education.

Her father was an athlete himself. It was Henry who got her hooked on playing baseball when she was around 10 years old. “My brother…used to teach me to throw and catch, and it seemed to come natural to me. I could always throw better than most girls. When I was at the age where kids throw stones at cats and hens I guess I hit the mark as often as any of the boys. When I got a little older I would join the boys playing one o’ cat, and a few years ago I had a chance to play in one of the scrub games near home and did well enough so they began to choose me for their teams regularly.” At a certain point, she said her father decided baseball wasn’t for a girl to play and thought she would quit. “But I went to look on at one of the games and got so excited I couldn’t stay out. As a fan I can’t keep still.”11

She enjoyed playing baseball, but was an accomplished athlete in other areas. The 1913 Journal article called her “an expert skater, probably the equal of any man of her age along the east shore and ice hockey is one of her favorite diversions. She has won prizes in various other contests, and there are few forms of athletics she is not able to join.”12 Some 25 years later, she told another writer, “It may sound strange, but do you know that mother never saw me play. She was always afraid I would break a bone or something, but I have never had a bad accident.”13

It was in baseball that she was able to play professionally, and for many years earned a living doing so.

In 1914, she played for the Warren Shoe team of the Manufacturers League and turns up in Providence’s Evening Bulletin article as the team’s first baseman.14 Warren Shoe won, 7-6, and “Miss Lizzie Murphy” was singled out in the brief news story, which said she had 12 putouts in the game, including a double play, and that in the fourth inning, with runners on first and second, she “lay [sic] down a fine sacrifice bunt.”15 The team scored three runs that inning. In a game Warren Shoe planned against the Railroad team of the Narragansett Amateur League on August 23, one of the opponents was Miss Margaret Sullivan, also a first baseman.16 One finds a number of games announced during Murphy’s career, but no trace of whether these games actually occurred.

Murphy consistently played first base, but she had been playing for scrub teams in the area for three years. Just the year before she had said that shortstop was her preferred position. And the Journal said she “has gained reputation as a pitcher also.”17

She played for several different semipro teams. On August 29, 1914, she was due to play for the East Providence Moose team. The New York, New Haven and Hartford team also featured a female first baseman, Marguerite Fontaine of Providence.18

A May 1915 edition of the same newspaper ran a photograph of her, glove on her left hand, saying she would be playing first base for Providence’s Independent A.C.19 She was right-handed, stood 5-feet-6, and said “my best playing weight” was 122 pounds. Her “braided hair was tucked under a baseball cap.”20

A game account in Fall River’s Evening Herald said, “She knocked down hard-hit grounders, gobbled up poor throws that would get away from many players, and at every time showed she knew the game.”21 She did get thrown out on an attempted steal of second, the throw from the Fall River Independents catcher beating her hook slide.

Providence Journal reporter Carolyn Thornton reports that in 1918, Murphy joined the Boston All-Stars, “a semipro team of former major league players,” and that “for the next 17 years she traveled the United States and Canada, playing over 100 games a season.”22 By 1920, she had acquired the nickname “Spike.”23

Scattered articles on Murphy turn up on web searches of newspaper databases. On August 8, 1920, she played first base for Manville Co, in their 2-0 win over J & P Coats of Pawtucket.24 On August 17, she was due to play for the Universal Winding Company team; she was described as the “noted woman ball player of Warren.” And she rated a headline on a small preview a couple of weeks later, when she was playing first base for Warwick A.C. against the Providence Gas Company team.25 On October 17, Murphy’s Providence Stars team lost to the Beverage Hill team, but it was said she “received much applause, especially in the eighth, when she hit over second base for a clean bingle.”26

She was often the only player named as being planned for these games, an indication that her inclusion in the game was seen as noteworthy and marketable. That said, she may have been taken advantage of once, earlier. Thornton explained:

Her only known confrontation occurred with a team manager when she played for a Warren team at the age of 15. In those days, spectators were not charged admission to semipro baseball games. Instead, a hat was passed through the stands and players would share what was collected.

In Murphy’s first game with the team, however, she received nothing. The following Saturday afternoon, as the team began boarding the bus for a game in Newport, Murphy refused to get on until the manager agreed to pay her $5 for every game, plus an equal share of the collection.

To supplement her small salary, Murphy would work the crowds between innings, selling postcards of herself in uniform for a dime.27

The following year, Murphy played with Eddie McGinley’s Providence Independents. That August, the Independents were scheduled to play against the Cleveland Colored Giants in a game at Rocky Point.28 Murphy was to play first base “and attempt to catch a ball dropped from an aeroplane.”29 The game was played on August 21, and the Independents won, 6-5, but the brief four sentences about the game have no mention of Murphy.30 Whether she actually played in the game remains unknown.

Other articles say she played—perhaps at a different time—for the Cleveland Colored Giants. We were unable to find any trace of a game involving any “colored” ballplayers, with Murphy on one side or the other. Several articles mention such a game, but without specifics. Sportswriter Dick Reynolds, more cautiously, said, “she is believed to have been the first woman ever to play on a black baseball club.”31 One source which provides some confidence that she did play for the Giants is a 1938 article from the Providence Evening Bulletin. Author Elizabeth L. Williams spoke with Murphy and reported, “She recalled playing at Rocky Point with the Cleveland Colored Giants, with the Athol Manufacturing Club against the East Jaffrey, N.H. team, and with the Lymansville team under Manager Neil Flynn, also with Jack Cooney, of Cranston, with the Boston Braves of the National League, and with many other outfits.”32

In a similar vein, we have been unable to find support for Jane Lancaster’s statement that in a later game in New York State, “she was very proud to have gotten a base hit off the legendary Satchel Paige.”33

McGinley acted as her manager; those wishing to book her were urged to write to him. He was a player on the Independents as well. For a game on September 11 to be played at Moosup, Connecticut, he was listed as the catcher for Roy Rock’s All-Stars and Murphy was listed at first base. The Norwich newspaper said of Murphy, “This young lady has a wonderful record on the diamond. The way Miss Murphy performs on first is remarkable and is worth going miles to see.”34 After the regular season was over, McGinley signed Boston Braves pitcher Johnny Cooney to join him and Murphy on the Independents.

She was clearly seen as a marketing benefit, and her number of appearances increased in 1922. Her uniform was one-of-a-kind, with “LIZZIE MURPHY” Emblazoned across the front instead of a team name.

She had other talents as well. “She keeps in condition by chopping wood and swimming. She also plays the violin.”35 The Boston Globe said she was active as both a mile and five-mile runner and swimmer.36 One newspaper said, “When she first began as a regular player, she felt people used to come see her because of the novelty. But as she improved and became a star, the spectators came to see an expert ballplayer at work.”37 Reynolds said, “Teammates did not seem to resent the public attention showered on Lizzie. Bigger crowds meant bigger collections and more money for everybody. Furthermore, Lizzie never flaunted her celebrity status.”38

A novelty she was, but the Springfield Republican advised readers, “Miss Murphy is not in the lineup just because she is a woman…She is there because she can play ball. She is hitting .300, no mean record with a fast semi-pro company as she travels with. Her fielding leaves nothing to be desired.”39

She played games in Malden, to the largest crowd ever for a twilight game in South Boston, and before a “huge mob” at Fore River Field, getting the first hit in a game the Independents lost, 1-0.40 A reported 10,000 who turned out at South Boston’s Christopher J. Lee Playground saw her execute a squeeze play to help beat Kelly’s All Stars, 6-3.41 She had proven herself to be “one of the best [semipro] first basemen in New England.”42

A number of days later, the Independents beat the New York, New Haven, and Hartford All-Stars, 8-1, at Boston’s Walpole Street Grounds with Murphy collecting two base hits and said to have “played a strong game.”43 It was her double in the top of the ninth that kicked off an eight-run rally.44

Her deportment was that of the other ballplayers. A note in the Post described her at first base awaiting the pitch with her hands on her knees and ready to spring into action. “Occasionally she spat into her mitt after the manner of other players and kept up a steady stream of talk to the pitcher, her chatter being clearly heard with its light tones.”45

THE FIRST WOMAN WHO PLAYED AT FENWAY PARK

Tommy McCarthy had most recently served as a Red Sox scout and the team helped organize the day in his honor working with a local committee headed by Jack Morse, Eddie McHugh, and John S. Dooley.46 Quite a party was prepared, including a presentation of vaudeville and dancing girls from the Love and Kisses Company prior to the game. Other entertainment came from the Bowdoin Square Theater and the Old Howard. Jimmy Coughlin’s 101st Regiment Band played and when the band struck up “Sweet Adeline” the demand for former mayor “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald to sing was so fervent and so persistent that he yielded to the call of the 4,000 or more in attendance, a crowd which included Mayor James Michael Curley and others. Congressman Gallivan was there and so were former ballplayers such as John Irwin and Jerry Hurley.

The program lasted for two hours prior to the 3:30 pm game on August 14.

Ballplayer, coach, and entertaining personality Nick Altrock worked the crowd, not only joining in the theatrical numbers but selling scorecards in the stands and shaking hands with several hundred children. Some of the dancing girls joined him in selling scorecards, but Altrock was the star of the show, and the game.

Murphy’s appearance had been trumpeted in advance but, given the uniqueness of the situation, not extravagantly so. Paul Shannon, writing in the Boston Post, gave her two sentences: “Lizzie Murphy, the famous lady first baseman, will be seen in the game for a while. She won’t launch any home runs but lady fans will get a peek at a sister who can cover that initial sack as many a big leaguer.”47 Another paper called her “the brilliant woman first baseman.”48

She was a novelty, of course, but a popular one. The Herald observed, “She had her picture taken so often that Nick asked her if she was running for Congress.”49

As noted, Babe Ruth couldn’t make the game, but the All-Star team Murphy joined was otherwise composed of American League ballplayers, with at least one representative from each AL club: Nick Altrock, Donie Bush, and “Sheriff” Earl Smith from the Washington Nationals; Tillie Walker, Ralph Young, Frank Bruggy, Bob Hasty, and Doc Johnston of the Philadelphia A’s; Chick Shorten of the St. Louis Browns; Ira Flagstead of the Detroit Tigers; Les Nunamaker and Jim Bagby of the Cleveland Indians; Hervey McClellan of the Chicago White Sox; and Fred Hofmann of the New York Yankees. Murphy started the game at first base, batting third in the order.

She was tested early on. The visitors, of course, were up first. Allen Russell was pitching for the Red Sox and he set down second baseman Young and the shortstop Bush. Murphy stepped into the box. Two outs, no one on base. She hit a grounder to Boston’s Johnny Mitchell at short and was retired. Mitchell, though, chose to showboat a bit throwing the ball to the second baseman Del Pratt who then fired to “Tioga George” Burns at first. Boston Globe writer James O’Leary took him to task in his game story the next day: “It was rather ungallant of Mitchell to play it this way.”50

With Boston batting against Bagby in the bottom of the first, her own teammate McClellan chose to challenge her as well. On a sharp grounder hit to him at third base, he fielded it cleanly, but then deliberately held the ball until the last moment and then fired a rocket to Murphy. She caught it for the putout. Gregorich reports that McClellan walked over toward Bush, nodded in the direction of first base, and said, “She’ll do.”51

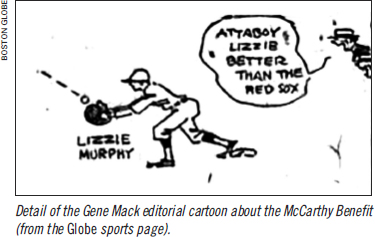

Murphy played just the one inning. The All-Stars scored in the top of the second. The Sox scored twice in the fifth, only to see the All-Stars come back to tie it in the sixth. Altrock cut the clowning, came in to pitch, and held the Red Sox scoreless for the final four innings, the visiting All-Stars winning the game, 3-2 in 10 innings. Doc Johnston, who had taken Lizzie’s place at first base, tripled in the winning run. This was not a strong Red Sox team. In fact, they finished the 1922 season in last place, 33 games out of first, with a 61-93 record. No wonder, then, that the Globe’s sports cartoon the next day depicted Lizzie Murphy making the play and one spectator shouting, “ATTABOY LIZZIE BETTER THAN THE RED SOX.”52

The game featured a couple of noteworthy fielding plays and a situation in the seventh when the Red Sox hit two triples but couldn’t score. Mike Menosky had tripled down the right-field line, but was soon picked off third by Altrock. Boston catcher Ed Chaplin then followed with another triple, but was left stranded on third.

Altrock got the win. “It seemed difficult, before the game, to visualize a tight, well-played contest,” wrote Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald. “But it was a good game and each team tried to win.”53 The Post’s Shannon gave Altrock credit for making the day a memorable success, a subhead on his column reading “Nick the Whole Noise.”54 The Post was, however, patronizing. Shannon wrote that Murphy got a big hand when she came to bat in the first inning, but said, contradicting what almost every other account over the years declared, she “hasn’t much of an arm but she is the cutest lady player that the fans have ever seen and her frenzied efforts to hit in response to Nick Altrock’s plea of ‘Come on, Murphy,’ made a hit with the fans.”55

Murphy hit third in the order. The Washington Post said she played two innings, was errorless in the field, and that “In her only time at bat, she grounded out at shortstop.”56 The Boston Globe boxscore presented all the male players by last name, but in Murphy’s case presented her name as “Miss Murphy 1b.” The exhibition raised between $5,000 and $6,000. Among those who could not attend but made a donation was Ty Cobb, who mailed in a check for $25.57

Two days later, Murphy played first base at Kinsley Park in Providence for Eddie McGinley’s All Stars.

AFTER THE GAME

As a celebrity, opportunities beyond baseball often presented themselves. She and McGinley paired up for a vaudeville sketch entitled “Headin’ Home” at the Bangor Opera House in August.58

Her fame spread. She played for Ed Carr’s All-Stars in 1923. A photograph of her ran in Canton, Ohio’s Repository the following year and the San Francisco Chronicle ran the same photograph, saying she was earning $300 a week.59 She had aspirations to become a major-league ballplayer “in another season or two,” according to the Milwaukee Journal. The article said she insisted her teammates not call her “Miss” on the diamond, and that she also enjoyed cooking, sewing, films, and reading.60

This was hardball and the appeal was that Murphy was playing with, and against, the top semipro and amateur ballplayers around New England. In a July game at Newport, Rhode Island, she suffered a serious hand injury that required several stitches.61 Back without losing too much time, her team beat Dorchester, 9-3, but she was then injured again against the Somerville Civic Club at a game in Medford, Massachusetts. Her hand was spiked in the fourth inning and she had to leave the game.62 One wonders if this may have contributed to the “Spike” nickname. Just a week later, she doubled in a game against the G. F. Redmond Co.63

In 1924 and 1925, Carr’s team was sometimes billed as Lizzie Murphy’s All-Stars, in recognition of her importance as a draw. News accounts did at times offer praise for her play: for instance a Boston Globe article that said she “once again proved that she is not a novelty but a clever woman player.”64 A subheading from the Patriot Ledger called her the “Female Sisler” and said, “Only the fact that women are barred from the big show keeps her from wearing major league spangles.”65 One of her teammates in 1926 was Buck O’Brien, formerly with the Red Sox.66 The two were booked to play in Fitchburg against the Philadelphia Colored Giants on July 5.67

Fielding was apparently her forte rather than batting. Boxscores typically showed her batting ninth and many showed her having been held hitless. There were more productive games, of course, such as her 2-for-4 game against Salem, Massachusetts, on April 23, 1927, in which she also successfully executed a sacrifice.68 One of those who played in the 17-inning game at Newport said, “Lizzie played the entire game and handled some 30 odd chances. As a fielder she was as good as the average man. At bat, she was only fair, though she did not flinch from the fastest pitch.”69

As one might expect, not all praised her talents. Jim Russell of the Philadelphia Inquirer offered a retrospective comment in 1956, while praising athlete Babe Didrikson Zaharias. He wrote, “In the 20’s, fancy words flew around the circuit about a first basewoman named Lizzie Murphy, who reached the zenith when she played with a group of major leaguers at Boston’s Fenway Park, home of the Red Sox. Not long after that achievement, Liz came to town to play against the local pros, and thousands turned out for a look. They saw a rather awkward girl play one inning at first, take a couple of soft throws from the infielders, and bat once against some delicately slow pitching, while thousands stifled their jeers.”70

How good was Murphy? Perhaps a more balanced appraisal came from sportswriter Dick Reynolds. “Many who watched Lizzie have contended that she could play first base with the best. That,” he wrote, “must remain uncertain. It is certain, however, that her performances produced few, in any, complaints… Even the American League All-Stars, skeptical at first, applauded her ability to cover ground, scoop up grounders with long, powerful fingers, and throw with an unerring arm. She was not a slugger. But her career hitting average was just below .300 and Carr considered her among his most dependable stickers.”71

Murphy was said to have played in a 1929 exhibition game involving the Boston Braves and some National League All-Stars (Dick Reynolds says American League All-Stars). As with the stories of her playing against Satchel Paige—whose own appearances were highly promoted—no such games have been found, despite diligent research and appeals to some of SABR’s best researchers. Perhaps it is the case, as one researcher suggested, that these are myths.72

One could posit a number of reasons that she does not turn up as much in newspaper database searches in the later 1920s, but there were at least occasional appearances noted such as in Marlboro, Massachusetts, when Lizzie Murphy’s All-Stars were to play the Marlboro Merchants in late August 1933.73

There was a standout game on July 4, 1932, in Newport, Rhode Island, between the Sunset League All-Stars and the Providence Independents that ran 17 innings. Hank Soar—later an American League umpire from 1950 through 78—was the catcher for Providence. The game was lost when, with runners on second and third, Soar dropped a two-out third strike and then threw to first but “threw the ball over Lizzie Murphy’s head.”74

Among those who had played with her All-Stars were said to be Pete Wood, brother of Smoky Joe Wood, and Bill Stewart, who was a scout for the Boston Red Sox in 1925 and 1926 and later a National League umpire from 1933 through 1954.75

Gai Ingham Berlage wrote, “Lizzie goes down in history as the first woman ever to have played against a major league team. In 1934 Babe Didrikson would add another first by actually playing for major league teams in major league exhibitions. Babe pitched a few innings for the Philadelphia Athletics against the Brooklyn Dodges and for the St. Louis Cardinals against the Boston Braves.”76 The distinction was that Didrikson’s play was during spring training exhibition games, not in a major-league ballpark.

After 18 years as a professional, Lizzie Murphy retired from playing baseball when she turned 40 and returned to Warren to work in the mills, and later worked on oyster boats out of Warren. She had other interests as well, and reporter Elizabeth Williams noted “several carved wooden toys, which she said she had made during the Depression.”77 On October 30, 1937, Lizzie married Walter Larivee of Warren, said to have been a supervisor in one of the mills. He had been raised there in a mill family, the 1900 Census showing his widowed mother Exilda, and her four oldest children all working as weavers in a cotton mill. Perhaps the Depression had an effect; Walter was listed in the 1940 Census at a laborer doing road construction. He was 11 years older than his wife. The marriage ended when he died six years later.

It was said that Murphy soured on baseball a bit, telling one visitor, “It’s hard to explain why I liked baseball so much. And the more I think about it the less I understand the reason.”78 She declined an invitation to dedicate a Little League field, and when some friends began planning a testimonial dinner for her, she said she would not attend.79 That said, retired Warren High School baseball coach Charlie Burdge said, “If you met her coming up from the river with a bucket of clams, she’d stop for a few minutes and talk baseball. She never put down the game. But, for some reason, she didn’t want any public appearances.”80

Nonetheless, Jane Lancaster quoted her as saying, after her retirement, “Eddie [Carr] used to tell me that I was the first girl to break into baseball with a man’s team as a regular player. You know that makes me feel mighty good.”81

At the age of 70, Elizabeth Larivee died in Warren on July 27, 1964, and is buried locally at Saint John the Baptist Cemetery. She was survived by brother Henry and sisters Lena Bouffard and Mary Ella Lynch.82 A brief note from the Associated Press said she had “gained renown in New England and Eastern Canada 40 years ago as Lizzie Murphy, a woman baseball player in an era when it was unusual to see a woman driving a car.”83

On the 100th anniversary of her birth, Warren declared “Lizzie Murphy Day” with Boston Red Sox VP Lou Gorman presenting a proclamation. The following month, she was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame.

BILL NOWLIN has enjoyed researching baseball and writing for SABR for nearly 20 years, and has also been active in editing or co-editing a good number of SABR books. He’s an active member of the Boston chapter, and spends a lot of time at Fenway Park.

Sources and Acknowledgments

Thanks to Barbara Gregorich, Leslie Heaphy, Jay Hurd, Jane Lancaster, Len Levin, Emily Arnold McCully, and Debra (Shattuck) Burton. Lizzie Murphy’s story is one of a woman who chose to be different. She seems to have had a rewarding life. One effort to tell her story to children ages 4-10 is Queen of the Diamond: The Lizzie Murphy Story by Emily Arnold McCully (New York: Margaret Ferguson Books, 2015). The game described in this article has been written up for SABR’s Games Project at SABR.org.

Notes

1. The biography initially draws on material the author originally had published in 2008. See Bill Nowlin, Red Sox Threads (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008).

2. Melville E. Webb, Jr., “McCarthy Game Monday,” Boston Globe, August 12, 1922, 4.

3. Barbara Gregorich, Women at Play: The Story of Women in Baseball (San Diego & New York: Harcourt Brace, 1993), 28. Of Murphy, Carr said, “She swells attendance, and she’s worth every cent I pay her. But most important, she produces the goods and, all in all, she’s a real player and a good fellow.” John Hanlon, “Queen Lizzie Plays First Base,” Sports Illustrated, June 2, 1965.

4. Gregorich, 29.

5. The Censuses from 1900 and 1910 only reveal six children in the family: Sarah, Eva, Henry (John in 1900), Mary (Elizabeth in 1910), Marylena (Lena in 1910), and Ellen (Ella in 1910). However, contemporary reporter Elizabeth L. Williams said she was from a family of five girls and two boys. “None of my sisters was a tomboy,” Murphy told Williams. Elizabeth L. Williams, “Warren Woman Recalls Life as Baseball Star,” Providence Evening Bulletin, February 2, 1938, 24. John was said to be 9 at the time of the 1900 Census and Henry was not listed; Henry was said to be 20 at the time of the 1910 Census, and John was not listed.

6. “‘Lizzie’ Murphy Larivee, 70, Onetime Ballplayer, Dies,” Providence Journal, July 29, 1964: 20.

7. This helped her in baseball at one point when playing a game in Canada. She overheard the opposition discussing steal signals in French. She improvised a signal to her catcher and they cut down base stealers “Nailed five of them that way,” she is reported to have said. Hanlon.

8. “Woman on First in Game at Ware,” Springfield Republican, May 30, 1922, 5.

9. “Warren Girl An Expert Baseball Player,” Providence Journal, July 27, 1913.

10. Debra Shattuck, “Playing A Man’s Game: Women and Baseball in the United States, 1866-1954,” Baseball History from Outside the Lines: A Reader, John E. Dreifort, ed. (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2001), 195-215.

11. “Warren Girl An Expert Baseball Player.” The age of 10 was cited in the Newburyport Daily News, October 7, 1923, 7. She said, “I used to beg the boys to let me carry the bats. Finally, I was allowed to join the team for only one reason: I used to ‘steal’ my father’s gloves and bats and bring them along, so I was a valuable asset to them when I could furnish some of the equipment.” Hanlon.

12. “Warren Girl An Expert Baseball Player.” She told Williams, “I used to skate and play hockey on the Kickemuit river down here, and I have a medal that I won for hockey.” Williams.

13. Williams.

14. The Warren Shoe team was organized by John Natal, who had a shoe store on Main Street in Warren.

15. “Warren Shoe 7, Railroad 6,” Evening Bulletin (Providence), July 20, 1914, 19.

16. “Railroads vs. Esmond,” Evening Bulletin, August 15, 1914, 14. Some of the other women playing baseball at the time who were mentioned in articles read during the research for this biography included Maggie Riley, Nellie Twardzik, Anna Murray, and Milly Hill.

17. “Warren Girl An Expert Baseball Player.”

18. “Double-Header at Crescent Park,” Evening Bulletin, August 24, 1914, 30. In researching Murphy’s career, one finds more announcements of games to be played than results of the actual game. This likely reflects promotional efforts before a game intended to bolster attendance. Finding a game story or boxscore of the game has often proven elusive.

19. “Miss Lizzie Murphy,” Evening Bulletin, May 15, 1915, 15.

20. Jane Lancaster, “R. I. woman was a hit in a man’s game,” Providence Journal, July 12, 1992, E-06. One article mentioned that at the end of a game, she took off her cap and her hair—normally braided during games—tumbled down. A 1920 article in the Boston Post put her at five feet tall and 125 pounds. See A.G. Donnell, “‘Fans Pan Me, But I Don’t Mind,’ Says Girl Champ,” Boston Post, August 1, 1920, 36.

21. “Nine Men and A Lady Beat Marks,” Evening Herald (Fall River, Massachusetts), August 30, 1915, 6.

22. Carolyn Thornton, “First ‘baseman’ shone in semi pro ball,” Providence Journal, March 29, 1994, A-02.

23. Donnell. This article offers Lizzie herself talking at some length about how she first became involved playing ball in Warren and some of the challenges she faced, such as opposing pitchers trying to bean her. How she got the nickname “Spike” remains unknown.

24. “Manville 2, Coats 0,” Evening Bulletin, August 9, 1920, 18.

25. “Miss Murphy to Play at Point,” Evening Bulletin, September 3, 1920, 29.

26. “Beverage Hill Team Wins,” Evening Bulletin, October 18, 1920, 31. This game drew 3,000.

27. Thornton. Having bargained for the compensation she received, she had—suggested Hanlon—been baseball’s first woman holdout. The postcards often sold well.

28. “Lizzie to Play,” Evening Herald (Fall River, Massachusetts), August 12, 1921, 12. The article said, in part, “Manager McGinley will have Lizzie Murphy on first base.”

29. “Game Sunday at Rocky Point,” Evening Bulletin, August 17, 1921, 19. The game against the Giants was postponed at least once due to rain, but advertised in the newspaper for September 4. The ad billed her as the “greatest girl first base player in the east.” See Evening Bulletin, September 3, 1921, 8.

30. “McGinley’s Independents 6, Cleveland Colored Stars 5,” Evening Bulletin, August 22, 1921, 19. The airplane is not mentioned, either.

31. Dick Reynolds, “Lizzie Murphy, Queen of Diamonds,” Old Rhode Island, April 1994, 14. Reynolds said that she was believed to have played first base for Giants (who were not a Negro League team, but were possibly a New England-based aggregation using a name that made them sound grander than they were.) There were other teams playing frequent semipro games in relatively small towns in the region, such as the Highland Colored Giants and the Philadelphia Colored Giants.

32. Williams.

33. Lancaster. Researchers trying to find any such game have come up empty.

34. “Rock’s All Stars Will Play in Moosup Sunday,” Norwich Morning Bulletin, September 10, 1921, 11.

35. “Karpe’s Comment,” Buffalo News, June 3, 1922, 16. Murphy later told Williams, “Do you know how I kept in training? You’d never guess— sweeping and beating rugs, and chopping wood, too. Chopping wood keeps one fit for running round the bases, or driving a fly to centre field. Yes, traveling on the road was pretty strenuous, but I was always rough and ready, and could take it. It didn’t bother me a bit. In fact, after playing a double-header, I was no more tired than at the start of the game.” Williams.

36. “Meet Miss Murphy, 1B,” Boston Globe, May 24, 1922, 11. A large photograph accompanied the article.

37. “Girl Softball Player Here Recalls ‘Lizzie Murphy’,” Fitchburg Sentinel, July 20, 1966, 10.

38. He added, “Personal publicity never cause her to change the size of her cap. She was polite to the press, but she never went looking for an interview.” Reynolds, 13.

39. “Woman on First in Game at Ware.” A large photograph of Murphy in a batting stance accompanied the article. The next day’s Republican had a story and boxscore. Ware pummeled the Independents, 13-1. She was 0-for-3, listed in the boxscore as “M’s M’y.” The article said her play had been “excellent” and equal to, if not better than, that of her teammates. See “Providence No Match for Ware,” Springfield Republican, May 31, 1922, 5.

40. For some reason, a player named Rivard ran for her but she continued to play in the game. The ovation she received on coming to bat was “the greatest…ever tendered at Quincy. It looked as though the cheering would never stop.” “Lizzie Murphy Stars as Fore River Wins Game,” Patriot Ledger (Quincy, Massachusetts), July 7, 1922, 6.

41. “Lizzie Murphys Slam All-Stars,” Boston Globe, July 12, 1922, 9.

42. “Newton,” Boston Globe, July 15, 1922, 6.

43. “Lizzie Murphy Gets Two Hits, Providence Wins,” Boston Globe, July 18, 1922, 7.

44. “Lizzie Murphy Starts Rally with 2-Bagger,” Boston Post, July 18, 1922, 11.

45. “Girl Diamond Player Shines,” Boston Post, June 18, 1922, 22.

46. John S. Dooley was involved with Boston’s American League franchise since before its inception in 1901.His daughter Lib Dooley was an enduring fan as well, and offered important encouragement to this author right from the start. John Dooley had witnessed the first night baseball game, in 1880. He helped secure the land on which Boston’s Huntington Avenue Grounds was constructed. A member of the Royal Rooters, he was present at the first World Series game ever played, against the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1903. Lib Dooley attended every Red Sox home game from 1944 until her final year, 2000. This author’s season tickets placed him about 12 rows behind her front-row seat. See appreciations of both John Dooley and Lib Dooley in Red Sox Threads.

47. Paul H. Shannon, “Nick Altrock Wins His Game,” Boston Post, August 15, 1922, 18.

48. “To Honor Memory of Tom McCarthy,” Boston Post, August 14, 1922, 14.

49. “For Auld Lang Syne,” Boston Herald. August 15, 1922, 10.

50. James C. O’Leary, “Great Benefit Nets More than $5000 for Tom McCarthy’s Family,” Boston Globe, August 15, 1922, 7.

51. Gregorich, 30.

52. Gene Mack, “Highlights at McCarthy Benefit” (sports page cartoon), Boston Globe, August 15, 1922, 7.

53. Burt Whitman, “Tommy McCarthy Day Goes Over the Top As Nick’s Stars Win, 3-2,” Boston Herald, August 15, 1922, 10.

54. Shannon.

55. Shannon.

56. Robert Fachet, “Groundbreaking Woman Finally Gains Spotlight,” Washington Post, April 12, 1994, D2. Why did she only play two innings? She said, “I would have liked more time in the game but we had 17 players and they all had to get in.” Dick Reynolds, p. 12. Fifteen players did play for the All-Stars, which included three catchers, three pitchers, and two left fielders.

57. O’Leary.

58. “See Famous Lizzie Murphy at the Opera House Tonight,” Bangor Daily News, August 2, 1922, 2.

59. “Lizzie Stars,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 24, 1923, 20. See also “Lizzie Murphy Signs Contract,” Fall River Globe, April 13, 1923, 20.

60. “Lizzie Aspires to Major Team,” Milwaukee Journal, August 31, 1923, 46. The New York Times Herald of Olean, New York, said she “has been making every possible contact to connect with a big league team.” See “Sport SnapShots,” Times Herald (Olean), October 24, 1923, 6.

61. “All Stars of Boston Win, Lizzie Murphy Injured,” Boston Globe, July 23, 1923, 8. Her team won the game, 6-2.

62. “Lizzie Murphy Spiked, Has to Quit Ball Game,” Boston Globe, August 17, 1923, 11.

63. “Lizzie Murphy Hits Double, But Carrs Lose,” Boston Globe, August 24, 1923, 10.

64. “Reading Defeats Carr’s All-Stars,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1924, 4. The subhead read: “‘Lizzie’ Murphy’s Clever First-Sacking Features.”

65. “‘Liz’ Murphy and Her Gang Coming Here,” Patriot Ledger (Quincy, Massachusetts), July 7, 1925, 2.

66. “Lizzie Murphy’s Team Coming Here,” Evening Gazette (Worcester, Massachusetts), June 22, 1926, 14.

67. “Fitchburgs Take One, Drop One in Independence Day Tilts; Red Caps Are Good Bell Hops,” Fitchburg Sentinel, July 6, 1926, 8.

68. “Lizzie Murphy Gets Two, But Club Loses,” Boston Herald, April 24, 1927, 29.

69. “Sports in the News,” Newport Daily News, June 25, 1965, 16.

70. Jim Russell, “The Night Babe Threw Her High, Hard One,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 28, 1956, 38.

71. Reynolds, 14.

72. “I do have the articles which mention she was to play versus a Black team, but nothing about her actually playing in that game. I think many of these myths are just that—myths, and as often happens, they have been passed along as fact, from newspaper articles to Lou Gorman’s book High and Inside.” Email to author from Jay Hurd, May 27, 2021.

73. “Lizzie Murphy to Play in Marlboro,” Worcester Evening Gazette, August 26, 1933, 2.

74. Bill Parrillo, “Oldtime ballpark survives behind glitter and glamour of Newport,” Hartford Courant, August 9, 1978, H6D.

75. For Stewart’s extensive professional history, see his Sporting News umpire card on Retrosheet, accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.retrosheet.org/TSNUmpireCards/Stewart-William.jpg.

76. Gai Ingham Berlage, Women in Baseball: The Forgotten History (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1994), 55.

77. Williams.

78. Hanlon.

79. Hanlon.

80. Reynolds, 15.

81. Lancaster.

82. “‘Lizzie’ Murphy Larivee, 70, Onetime Ballplayer, Dies.”

83. “‘Lizzie Murphy’ Rites Today,” Springfield Union, July 30, 1964, 44.