Black Women Playing Baseball: An Introduction

This article was written by Leslie Heaphy

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

The fiftieth anniversary of the passage of Title IX of the Higher Education Amendments of 1972 gives us an opportunity to reflect on its impact on women’s sports as a whole and on specific sports such as baseball. Women’s participation has been overlooked and marginalized in most publications and general discussions about the sport. Title IX improved opportunities and paved the way for the progress we are seeing in 2022. However, before and after the passage of legislation, the contributions of Black women in baseball has been largely overlooked and ignored. Few books or articles exist and those that do focus on the names of only a few owners and players such as Effa Manley, Olivia Taylor, Toni Stone, and Mamie Johnson. Their stories are important but are just the tip of the iceberg.

What is presented here is an introduction to the incredible contributions made by so many Black women as players, owners, coaches, and other baseball personnel. The primary focus centers on those most readers are not familiar with as a result of the attitudes of the times that showed a disdain for women of any color playing baseball. News coverage of women playing baseball was limited and often not complimentary in tone. For Black women the press coverage was worse because they were up against issues due to sex and race.

The recent recognition by Major League Baseball of the Negro Leagues as having major league status raises people’s interest in the women who owned and worked for Negro League teams as well as those who played in the Negro Leagues or against Negro League teams. Who are some of these women and on whose shoulders do they stand? Who came before Effa Manley or Toni Stone? The story of Black women in baseball generally begins with the story of the Dolly Vardens and travels all the way to the present with the recent hiring of Bianca Smith by the Boston Red Sox as a coach in their minor league system.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, there were two Dolly Varden teams that played around the Philadelphia area. Little is known about either of these teams since news stories from the nineteenth century have always been limited in number and coverage. Often the writers talk about the uniforms more than they did the players or the score. Often only first names were given or players were simply called “Miss.” This makes it difficult for researchers to track down the players. We know the Dolly Vardens appeared in the papers in 1883 and there is mention of them reorganizing for 1884, though no games have been found to date. When The New York Times covered the team in 1883, we are informed that Miss Ella Harris was the team captain. The opposing team missed the train and never showed up. The remainder of the article focuses mainly on the Vardens’ red jockey caps and the different-colored calico dresses the players wore. We learn the names of some of the other players: Sallie Johnstone and Molly Johnstone playing first and second base, Lizzie Waters listed as the third baseman, and Ella Waters behind the plate. The three outfielders were Agnes Hollingsworth, Ella Johnson, and Rhoda Scholl. Cora Patten handled the pitching duties. Unfortunately, that is about all we know. These young ladies got a chance to play baseball, but given the way reporters covered women’s sports and attitudes towards Blacks at the time, the only other thing learned from the articles is the racism of the day, as shown by the dialect the white writers attributed to the women ballplayers.1

One of the opponents for the two Dolly Varden clubs also played in Philadelphia and were called the Captain Jinks Base Ball Club. Even less is known about this club, though the three teams seem to have been created by a white man named John Lang. Lang thought the novelty would bring out fans and the clubs would make him some money. The lack of news coverage has made it difficult to recover their games.2

Papers continue their sporadic mention of Black women’s ball clubs with a few references appearing in 1902 in Missouri, North Carolina, and Kansas. Beyond mentioning games were planned for the Biddleville (NC) Colored Women’s Baseball Club, the details are sparse.3

St. Louis hosted the Black Bronchos in 1910 and 1911 under the leadership of Conrad Kuebbler. His brother Henry played baseball while Conrad appears to have been an organizer. The Bronchos found themselves playing in Tennessee, Missouri, Kansas, Kentucky, and Oklahoma, showing their ability to secure games across the country. Few scores have been found for their games, but they did beat the Nashville Giants 2-1 in one 13-inning contest while losing to the Columbia Cubs 5-3. They also lost two games to the Madisonville, Kentucky club, 10-9 and 6-3. The Plain Dealer (KS) in 1911 carried an ad touting the team as the “only Female Negro Team on the road.” The same ad also called the girls “…a novelty attraction but also a strong team of well-behaved girls.” The article captured the general attitudes of the day toward women playing any sport, which was usually not complimentary, hence the need to point out these “girls” behaved well and were playing for the entertainment of the crowd, not because they should be viewed as serious ball players.4

The Colored Havana Stars had a new attraction in 1917 with Pearl Barnett playing first base for the club. An article announcing the team’s season opening on May 27 listed Barnett as the only Black female first baseman playing for a colored team in the country. Their owner, Dr. Joseph Plummer, had hoped to put together a solid team to barnstorm the country. No full accounts of her contributions have been found to date.5

The most well-documented team in the 1920s was the Baltimore Black Sox Bloomer Girls playing in 1921 and 1922. A featured opponent for the Black Sox were the famous New York Bloomer girls (a White team). In one 1922 game, the visiting New York squad pummeled the Black Sox, defeating them, 48-2. The Black Sox only had two hits, by their pitcher and catcher. The Black Sox lost another contest, 51-2 which suggested they did not get much chance to practice. One of their closest games came in August 1921, when they lost to the Excelsior Sparrows, 17-14, which led to a second contest later in the month. That game ended in a 29-29 tie, highlighted by four home runs, two by each team. The Black Sox finally pulled out a win in early September, coming out on the good side of a 32-31 score. The hitting was led by the right fielder Miss Clark. The two teams played a fourth contest that the Black Sox won, 34-11. The Black Sox relied on four home runs and the pitching of B. Taylor, who struck out six.6

Isabelle Baxter joined the Cleveland Giants of the Negro National League in 1932 and parts of 1933. She played second base and was expected to be there for the two seasons, though it appears she only played for part of 1932, after the Giants left the league to play independently. In the Giants’ first game, which they won over the Canton Clowns, Baxter handled five chances at second base with only one bad throw to first. At the plate Baxter had one hit but also two long balls into the deep outfield.7

Women’s baseball had their first and strongest league during World War II with what is now known as the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL).8 No Black women played in this league, but seven young ladies from Cuba were invited to play starting in 1948. Mamie Johnson and a friend went to one of the tryouts but were sent away. For Johnson, that led to her being signed to pitch in the Negro Leagues with the Indianapolis Clowns in 1955. She joined the team with outfielder Connie Morgan from Philadelphia. Morgan and Johnson became the second and third women to play professionally in the Negro Leagues. The first was Marcenia (Toni) Stone, who played for the Clowns in 1953 and then for the Monarchs in 1954. When she was traded to the Monarchs, she was replaced by Johnson and Morgan. Desiria “Boo Boo” Robinson and Doris Jackson also appeared on the Clowns’ roster for a short time. The AAGPBL received more coverage than any other women’s baseball in history, mainly because of the timing. Philip Wrigley came up with the idea to keep people entertained during the war because so many male players served in the military. After the war was over, the league was expected to end. When it did not, the coverage and attendance slowly began to decline leading to the league’s demise after the 1954 season.

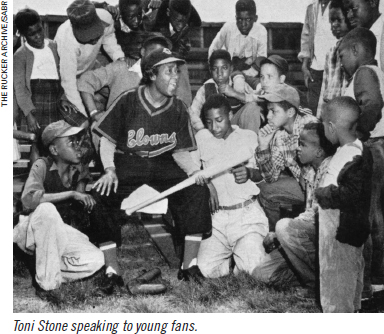

Stone played baseball all her life. She loved the game and wanted to learn as much as she could. Growing up she got a chance to go to a local camp to better her skills. Her mother was not happy with her playing, as she did not think girls should play baseball with the boys, but Stone continued to play. By 1938 Stone, was playing for a Connorsville team and then she moved to play with teams in California and eventually the New Orleans Creoles. From the Creoles she got noticed and was able to join the Kansas City Monarchs and Indianapolis Clowns. While playing in the NNL in 1953 and 1954, Stone proved she was not just a fan curiosity but could play the game. She was actually voted to play in the East-West Classic as an All Star after hitting .254. A news reporter described her play in 1953: “a sparkling fielder and holds her own at the plate.”9 Owner Syd Pollock, who signed her for a reported $12,000 in 1953, made it clear she was his starting second baseman and not just a novelty. In recognition of her accomplishments, a field was later dedicated in her honor in her hometown of Minneapolis and a play was written to celebrate her life.10

Morgan played baseball in the Philadelphia area as a teenager, but was better known as a basketball player for the Philadelphia Rockettes. She played for the Northern Philadelphia Honeydrippers team from 1949 through 1953, where the papers claimed she hit over .300. Morgan played second base under manager Oscar Charleston for 49 games. She proved she was more than just a gate attraction in her first game, making a stellar fielding play and walking twice. Where Morgan seemed to be most recognized was in her ability to lay down a solid bunt.11

Johnson, better known as “Peanut” due to her short stature, pitched on local sandlot teams before being signed with the Clowns. Before joining the Clowns, Johnson had played on many local semi-pro clubs in New Jersey and Washington, DC, where she lived. She compiled a 3-1 record in her one season. Johnson turned the loss of a chance to play in the AAGPBL into an opportunity to be one of the first professional female pitchers in a men’s league. After her playing days ended, Johnson worked as a nurse and later ran a Negro Leagues memorabilia shop in Washington. Johnson got recognized by MLB when they had each team draft a Negro League player. She was taken by the Nationals since she lived in Washington.12

In the late 1940s, two other young ladies played for the New Orleans Creoles when they were under the ownership of Allan Page, a Negro Southern League executive. Page signed two university students in Fabiola Margaret Wilson and Gloria Dymond, who played for the Creoles in 1948. Dymond attended Southern University while Wilson went to Xavier. Dymond was a senior physical education major when she joined the Creoles to patrol the outfield alongside Wilson. Both ladies received praise from their manager Tiny Brown as being as good as any man on the team. Hank Rigney, longtime baseball promoter and owner of the Toledo Crawfords, told reporters the ladies were on the team because of their abilities and not simply as a gate attraction. He said they had great arms and judged fly balls well. Rigney was responding to a common question found in much news coverage of women ballplayers, could they really play or were they signed as a novelty or curiosity?13

After the decline of the Negro Leagues and the demise of the AAGPBL, women’s baseball did not appear in any significant news coverage until after the passage of Title IX in 1972. When the Colorado Silver Bullets (a women’s professional team sponsored by Coors) began play in the 1990s, two African American women made the roster, Charlotte Wiley and Tamara Holmes.

Wiley pitched briefly for the 1994 Bullets. A graduate of Richmond High School in 1987, Wiley attended Cal State-Hayward. Holmes was one of two African American players on the Silver Bullets and also one of two African Americans on the USA National team.

Holmes began playing baseball in Little League and also played in high school. Those experiences helped lead Holmes to play for the Bullets in 1996 and 1997 until they lost their support from Coors after the 1997 season. She resumed her baseball play with the USA National team and became their mainstay at the plate and in the outfield since the mid-2000s. Holmes did not join the first team founded in 2004, preferring to play on men’s teams where she thought the overall quality of play would be better. In 2006 she tried out and made the women’s team, playing again in 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2016. In her last World Cup, Holmes batted .722 in seven games to lead the team. In 2012 Holmes was named the USA Baseball Sportswoman of the Year. In addition to her playing, Holmes is also a firefighter and owner of a CrossFit gym.

Another African American woman on the USA National team was Malaika Underwood, who joined in 2006 and played in every World Cup since then. Between them Holmes and Underwood own most of the batting records for Team USA. Underwood was twice named to the World Cup All-Tournament team. In 2019, Underwood played in all seven games for the Pan American championship, batting .483 and driving in 14 runs. For the World Cup team in 2016, Underwood batted .579 in seven games. Underwood also played volleyball for the University of North Carolina.

Just as numbers of male African American ball players have declined, there have also been few Black female players as other sports compete with baseball today.14

An exception to the lack of coverage most Black female baseball players have received is Mo’ne Davis. Davis made national news pitching and winning in the Little League World Series in 2014. She pitched an 8-0 shutout for the Taney Dragons over Newark, Delaware. After gaining national fame, Davis played basketball at Chestnut Hill Academy and now is attending Hampton University to play second base for the softball team. Davis also had the opportunity to meet and talk with Mamie Johnson on a 4000-mile trip around the country with the Anderson Monarchs in 2015. Johnson came out to see Davis pitch when the team traveled through Virginia. The meeting of the two ballplayers helped popularize Johnson’s career fifty years after she had played. Davis received better and more extensive coverage because the emphasis on women’s sports in the last two decades has grown in general. As women have continued to make inroads into sports since Title IX the effort to cover their play has also increased in quantity though the quality is sometimes more focused on them as women than as ballplayers.15

Black women have played baseball since the nineteenth century, though their story is not often part of the baseball record provided by the press. The introduction to their stories as presented here is just that, a chance to understand just how much is missing from baseball history by leaving out the play of Black women as individual players and those playing on all-Black female teams. The story of the Dolly Vardens and the St. Louis Black Bronchos to the recent play of Mo’ne Davis all paint a picture of participation worthy of learning and appreciating.

LESLIE HEAPHY was elected to the SABR Board of Directors in 2010. She has been a member of SABR since 1989 and chair of the Women in Baseball Committee since 1995. She is on the board for the International Women’s Baseball Center. Leslie is an associate professor of history at Kent State University at Stark and publishes in the areas of the Negro Leagues and women’s baseball. In 2008, she became the founding editor of the journal Black Ball, published by McFarland. She lives in Canton, Ohio. She was the 2014 winner of the Bob Davids Award, SABR’s highest honor.

Notes

1. “Miss Harris’s Baseball Nine,” The New York Times, May 18, 1883; Detroit Free Press, May 22, 1993, p. 6; “Dolly Varden No. 1,” The Times (Clay Center, KS), June 28, 1883, 6; some details included in an article in the program for the 2020 Women in Baseball Conference.

2. Louisville Courier-Journal, 2 May 23, 1883.

3. Wilmington Morning Star, June 19, 1902, 1; Chariton Courier (MO), July 18, 1902, 5; Topeka Dally Capital, July 25, 1902, 2.

4. Topeka Plain Dealer, July 7, 21 and July 28, 1911, 6; Daily Hustler (KY), August 19, 1911, 3; The Tennessean, July 20, 1910, 5; Columbia Herald, August 5, 1910, 5; Leavenworth Times, August 27, 1910, 8.

5. Chicago Defender, May 12, 1917.

6. “Girl Nines Play Ball,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 12, 1921, 2; “Girl Nines Tie in Hot Contest,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 26, 1921, 2; “Girl Nines Fight Another Close Battle,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 9, 1921, 6; “Girl Nines Stage another Game,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 23, 1921, 9; Baltimore Afro-American, May 19, 1922, 9; “N.Y. Bloomer Girls Swamp B. S. B. Girls,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 25, 1922, 12; North Adams Transcript (MA), June 20, 1923, 8.

7. “Girl Ballplayer Aids Cleveland 9,” Chicago Defender, June 17, 1933, 11; “Girl 8 to Play 2nd Base,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 27, 1932.

8. The league underwent a few name changes during its existence but is now universally referred to as the AAGBPL.

9. “Pro Negro Teams Meet Here Tonight,” Ponca CityNews(OK), August 11, 1953, 9.

10. Alan Ward, “On Second Thought,” Oakland Tribune, March 25, 1953, 46; “Woman is Star,” The Ponca City News (OK), August 11, 1953, 9.

11. “Miss Connie Morgan,” Miami-News Record (OK) May 23, 1954, 4; “Feminine Phil Rizzuto,” Battle Creek Enquirer, July 25, 1954, 28; “Clowns 10, Barons 6,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 29, 1954, 15.

12. “The Second Baseman was a Lady,” Philadelphia News, October 18, 1997, 18; “Indianapolis Clowns List Two Women on Ball Roster,” Birmingham World, May 4, 1954; Michelle Green, A Strong Right Arm (New York: Dial Books, 2002.)

13. “Mixed Baseball Team Plays Oliver’s Sunday,” Battle Creek Examiner, July 9, 1948; ”Studebaker Opponent has Two Girls in its Lineup,” South Bend Tribune, July 7, 1948, 23; News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, MI), July 12, 1948, 6.

14. Malaika Underwood, USABaseball.com, accessed March 8, 2022. https://www.usabaseball.com/player/malaika-underwood-x0281; Overall statistics for the 2006 Women’s National Team, USA, WNT History, accessed March 8, 2022. https://img.mlbstatic.com/opprops-images/image/upload/opprops/jkc33soxqgngh7mqs5ob.pdf.

15. Chris Bengel, “Mo’ne Davis, Former Little League World Series Star, Makes College Softball Debut for Hampton,” CBS Sports, February 10, 2020, accessed March 8, 2022. https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/monedavis-former-little-league-world-series-star-makes-college-softball-debut-for-hampton/; Zachary Silver, “Mo’ne Davis Honors ‘Peanut’ at Mural Unveiling,” MLB.com, July 12, 2018, accessed March 8, 2022. https://www.mlb.com/news/mo-ne-davis-honors-mamie-peanut-johnson-c285500306.