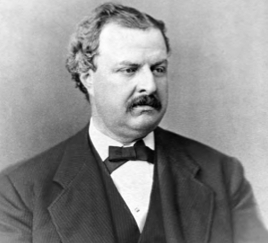

William Hulbert: Father of Professional Sports Leagues

This article was written by David Bohmer

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

As the 1875 baseball season approached, William Hulbert, the president of the Chicago White Stockings, was livid.

Chicago’s entry in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NAPBBP) had attempted, prior to the end of the 1874 season, to sign their star shortstop, Davy Force, for the next year. Such a move violated the Association’s guidelines stating that no player could be signed before the current season was finished. After the season ended, Force inked contract with the Athletics, one of the Philadelphia teams in the Association.

Chicago’s entry in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NAPBBP) had attempted, prior to the end of the 1874 season, to sign their star shortstop, Davy Force, for the next year. Such a move violated the Association’s guidelines stating that no player could be signed before the current season was finished. After the season ended, Force inked contract with the Athletics, one of the Philadelphia teams in the Association.

While the evidence isn’t clear, Force may have been offered more money. He also could have feared that his Chicago contract was invalid, having been signed prematurely. The two contesting teams protested to the Association and at its annual meeting the judiciary committee awarded Force to the White Stockings.

Later in the spring, however, another Association meeting was held, a new president was elected from Philadelphia, the judiciary committee reconvened, and Force was now awarded to the Athletics.1 Hulbert fumed. His correspondence with Harry Wright at the time indicates that the Boston manager shared his anger.2

Beyond the unfavorable Force decision, many other issues upset Hulbert about the Association. Few in 1875 could imagine that Hulbert’s anger would cause him to take the initiative in starting a new league, and no one imagined it would precipitate a revolution in American sports. But he began plotting to change things.

While the ultimate creation of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs in early 1876 was a major surprise to most of the baseball world, Hulbert had already made public his general intentions through his mouthpiece, the Chicago Tribune, in October 1875. Published without attribution by Hulbert’s close friend, Tribune editor Lewis Meacham, the article was entitled: “Baseball: A Vital Question for 1876.”

In it, Hulbert laid out much of what bothered him about the Association, especially the lack of organization of many teams. “A glance over the ball field for the season now nearly closed presents a problem for 1876 of more than ordinary importance to the game as an exhibition. The Brooklyn Atlantics are a sample of too many professional clubs; they had never any organization, any association, any backing, or any elements of permanency or responsibility of any kind; they were simply a gang of amateurs and rejected professionals, who played such clubs as they could get to come to them, and shared the proceeds. They were not even a mob, for a mob must have a head…. No one supposes that they ever intended to play any western games; they simply entered the ring to force clubs to play as many games as possible with them, they taking two-thirds of the receipts as on home ground…. First-class visiting clubs under heavy expense have lost money every time they played with them, while the two-thirds which went to the gang was reason enough to get on as many games as they could.”3 In essence, Hulbert argued, the association had too many weak teams draining the resources of the better organizations and, in particular, taking advantage of the western clubs.4

Hulbert’s treatise went on to propose remedies, many of which foreshadowed his new creation, one which came about the ensuing February. “What can we do about it?…[I]f 18 clubs come into the ring next year, the poorest half of the list will utterly swamp the whole and destroy the prospects of the whole game. At the same time, the managers say they can hardly see how to keep the duffers out. It has been the custom to vote everybody in who applied….The remedy is not difficult… First: No club should be allowed to enter for the championship unless it be backed by a responsible association, financially capable of finishing a season when begun…. Second: No club should be admitted from a city of less size than 100,000 inhabitants….Third: No two clubs should be admitted from the same city.…Fourth: The faith of management of a club should be shown by the deposit of $1000…in the hands of the association before the season begins….[I]t will be the plain duty of the nine clubs named to withdraw from the association as it now stands, and form an organization of their own – a close corporation, too.”5

Reduce the number of teams mentioned by one and the entry fee by $900, and you have the league that Hulbert brought into being a few months later, a feat Henry Chadwick—taken completely by surprise—called “a startling coup d’état.”6

The NAPBBP had been a revolution in its own right, established in March 1871 following a series of ongoing disputes with its predecessor, the National Association of Base Ball Players, over whether players should be amateur or professional. A leading proponent of the new organization was Chadwick, who understood the changing reality of the game as an increasing number of teams, following the example of the Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1869, had begun openly paying their players.7 In 1868, Chadwick noted that “the rules prohibit players from receiving compensation, but there is scarcely a club of note that has not infringed the rule.”8

The new Association resolved the professional question, but also created a host of other problems. Charging a mere $10 entry fee per team, the Association never could afford any central administration, control over scheduling, ability to enforce competitiveness, or means to clamp down on rampant gambling at the parks or the fixing of games. It was common for a visiting team not to show up for a scheduled game. Western teams often failed to travel east for games and eastern teams likewise would not show up in places like Chicago. Competitive balance was a joke. In the last year of the association, the Boston Red Stockings won with a 71–8 record, while the pitiful Brooklyn Atlantics, the team Hulbert referred to in his treatise, finished 2–42.

During the season, 7 of 13 teams folded.9 Alcohol and gambling were prevalent at many games, and rumors of game fixing inundated the baseball press. At its core, the Association wielded no control.

When Hulbert wrote his treatise for the Tribune in late 1875, then, his complaints were justified. Even a strong supporter like Chadwick recognized the need for reform, especially in removing the gambling and drinking elements from the ballparks. Even solving those problems, however, would not address the scheduling and competitive woes plaguing the Association. With no governing organization to oversee the operation and address the challenges facing the professional game, it appeared that little could be done to fix the problems.

While these shortfalls have usually been offered as the motivations for Hulbert’s push for reform, skeptics offer another factor: His fear that his White Stockings might be expelled from the Association in 1876.

Hulbert certainly thought that a strong baseball team was an excellent way to promote the city he loved so deeply. In his anger over the Force decision, he decided during the 1875 season to build as good a team as possible. The dominant Boston team was the logical place to start, and their star pitcher, Albert Goodwill Spalding, a sensible recruit since he was a Northern Illinois native. It is somewhat unclear who approached whom, but before the season was over Hulbert had signed Spalding and three other Boston standouts to contracts.10 Hulbert supposedly told Spalding, “You’ve no business playing in Boston. You’re a western boy and you belong right here.”11

The Boston press was outraged when the news broke before the end of the 1875 season. But the negative press did not stop Hulbert. Perhaps as revenge, he raided the Athletics and signed Adrian “Cap” Anson, who would become Chicago’s superstar and manager for well over a decade. While these signings might not have actually violated Association rules, they certainly provoked the Boston and Athletic clubs. Perhaps his fear of revenge from those clubs gave Hulbert additional incentive to create a new league.12 That effort would culminate in New York City on February 2, 1876, with the announcement of the formation of the National League.

While the outcome of the New York meeting is well documented, little is known about what took place during the actual session. One lingering legend is that Hulbert assembled the hostile eastern clubs in his hotel room, locked the door, pocketed the key, and told the representatives they could not leave until they had reached a decision.13 While fascinating, this unverifiable story does not seem realistic. More likely is the suggestion that Hulbert met individually with each of the eastern clubs privately before the group meeting on the second, just as he had already done with the western teams.14 With such groundwork laid before the larger assembly met, Hulbert could rely upon both his forceful personality and the logic of his plan.

The bedrock of the National League (NL) was an alliance between Hulbert and Harry Wright of Boston—surprising indeed given that the Chicagoan had just signed four of Wright’s stars. Despite the pair’s personal history, however, Boston had many reasons to give serious consideration to Hulbert’s proposal.

First, Boston and Chicago had been the two most profitable organizations in the NAPBBP. Boston, like Chicago, had been hurt by the weaker clubs, through lower attendance and forfeited games when the poorer team failed to show. Wright, who had managed the Cincinnati club, baseball’s first openly professional team, was also bothered by the poor play of the weaker teams, a point driven home by Boston’s dominance of the Association in 1875. He was also concerned about the 15 new clubs seeking to join the NAPBBP in 1876, believing that a limited number of teams in the largest markets would assure greater competitiveness.

On December 17, 1875, owners of the NA’s four Western teams (Louisville, Chicago, St. Louis, and Cincinnati) convened to create the pact between them for a new organization.

The Davy Force affair especially bothered Wright because it underscored Philadelphia’s heavy influence in the Association. From available correspondence, it is clear that Wright was aware and supportive of the Louisville meeting intended to create a bond between the Western teams.15 Given that strong philosophical agreement, Wright could overlook the loss of his players, thus creating a Chicago/Boston alliance that proved instrumental in the early years of the National League.16

The broader climate of the 1870’s also underscored the salience of Hulbert’s proposal. The rapid urbanization of the northeastern and Midwestern segments of the country provided larger populations from which a baseball team could draw. Industrialization, which helped drive the population growth in cities, also provided more affluence and more leisure time for spectator activities. The post-Civil War era was also a period of rampant capitalism, of stock companies and private investors fostering economic growth with abundant support from favorable government policies. Industrial capitalism also brought about a more pronounced division between owners and management on the one hand and labor on the other.

With all these changes came new waves of immigrants, still mostly Irish and German before 1876 but eventually also Eastern Europeans and Italians. All of these currents in the United States impacted how the National League was structured.

The name of Hulbert’s new league reflected in itself the changes capitalism was bringing to the country. The old organization was called the National Association of Professional Base Ball PLAYERS. The new organization was to be called The National League of Professional Base Ball CLUBS. Whatever remnant of player involvement in club leadership had remained in the Association would now, in Hulbert’s league, disappear. His creation fully reflected the division between capital and labor and firmly put the players in the latter category.17 As Harold Seymour noted, for the players “democracy was conspicuously absent in the league constitution. The players had no franchise, no elected representatives, no voice in the conduct of affairs. They could not get justice through a trial of their peers but, as in feudal days, must depend on the court of their overlords.”18 This same state of affairs would loom large for nearly one hundred years.

The other difference in the name, of course, was the change from “association” to “league.” The latter term codified the intent to create a stronger and rigid structure. “League” derives from Latin roots meaning “to bind,” and the word had connotations of a solid military or political compact; “association” had much looser connotations of “coming together for a common purpose.” Both name changes reflect fundamental shifts in the organization of professional baseball that continue to shape the game.

Beyond the changes in nomenclature and the impact of those new terms, Hulbert’s new constitution contained four fundamental points. The first and most significant of these was the creation of territorial rights. In every established market, only one team was to have the exclusive rights to field a professional baseball team. In essence, a ball club was granted a monopoly—at least in the new league—in its given population center. This eliminated competing NL teams in New York and Philadelphia and established the structural basis for every baseball league (and, indeed, every other American professional sports league) established since.19 Along with the division of capital and labor, territorialism may have been the single most important contribution of the new league.

Market monopoly, however, was not the only major change. The National League constitution also prohibited teams from markets with a population of fewer than 75,000. Initially, a limit of 100,000 had been proposed by Hulbert, but league member Hartford, with only 37,000 people as of the 1870 census, would have been an exception under any such rule. As events were to play out, other smaller cities were later added out of necessity, showing that the NL would simply ignore its population limit when deemed necessary. Other stipulations required that all teams were to play their entire schedule of games with the other members, five home and five away, and were restricted in the number of games they could play against clubs outside the league. League members could not play any outside team that came from the city of another member team. Finally, each member team was to contribute $100 a year to the League, ten times the fee required by the association. Those dues went to the establishment of a central governing office and the creation of a permanent secretary-treasurer, to be paid an annual salary of $400. To oversee the league, a five-member governing board was established, with members serving one-year terms. One board member was to be elected president by the others. The constitution also allowed for any misbehaving player to be blacklisted and left unable to sign with the other teams. A formal blacklisting policy, developed later, was one of Hulbert’s last innovations before his untimely death.20 In one fell swoop, the new league had addressed the problems of ownership, market placement, scheduling, and organizational control.

Especially notable is how closely the new constitution echoed the original proposal Hulbert had put forth in the Chicago Tribune back in October of 1875. Weaker clubs were eliminated and gaining membership was difficult. Teams now played set schedules and were limited in their ability to play non-member clubs. They were to enter with strong financial backing and without player involvement in ownership or governance. All teams were given territorial rights in a specific market, and those markets had to have a minimum population level. Teams had to pay high membership dues to create a strong infrastructure for overseeing league operations. It is impressive how much of Hulbert’s original vision was actually executed at the February meeting.

The league’s first season, however, would prove to be difficult. Its initial success was, at best, mixed. It certainly did not surprise anyone that Chicago dominated the league, finishing ahead of Hartford, 38 wins to 34. The club’s player acquisitions the year before had clearly paid off. This success also enabled the White Stockings to be the NL’s only profitable team during the first season. If competitive balance had been an objective, it was not achieved. The Athletic team finished 14–45–1, and they weren’t nearly as bad as Cincinnati, which won 9 and lost 56.21 There was clearly more work to do. By far the largest disappointment, however, came from the failure of both the Mutual and Athletic teams to complete their schedules; both reneged on one trip to the western cities.

This presented the League with its first major crisis. A set schedule, fulfilled by all teams, was one of the central points of the NL’s constitution. Exacerbating the problem was the fact that the two disobedient teams were in the League’s largest markets. How the NL disciplined the teams would say much about how seriously it took its constitution. At the annual meeting after the 1876 season, with Hulbert presiding, both New York and Philadelphia were removed from the League, which would play with only six teams in 1877. Retroactively, games played against the two expelled teams would no longer count in the official 1876 NL statistics.

A variety of factors played into this decision. Both New York and Philadelphia had competing professional baseball clubs, making it virtually impossible to enforce territorial exclusivity. Both cities’ NL entries had problems with gambling and drinking among the players, and, in Philadelphia, friction remained from Chicago having signed Cap Anson.22 Nevertheless, by removing the teams in the two largest markets for failing to meet their commitments to the League, Hulbert sent a clear and powerful message that the authority of the National League preempted the individual clubs’ right to conduct business as they saw fit.

The removal of two of the charter clubs was only the first of many challenges the National League would face in its early years. Each season seemed to present Hulbert with a new problem, and each time the League’s response set precedents that would help shape future professional sports leagues. 1877 brought a major gambling scandal. In 1878, the League responded to the threat posed by the recently created International Association of Professional Base Ball Players. The following year, in implementing the reserve rule, the League responded to high personnel costs and players jumping from team to team. In 1880, the major challenge came from the renegade behavior of the Cincinnati club, which chose to ignore the League’s generally accepted policy banning alcohol. Following the 1881 season, the National League faced its biggest challenge to date—the creation of the rival American Association, with most of its teams in larger population markets. In all of these crises, the response under Hulbert’s direction had significant impact for the long term.

Since the National League had been founded, in part, to help stem baseball’s ties to gambling and corruption, the actions of some Louisville players, especially Jim Devlin, presented Hulbert with a crisis in the league’s second season. Louisville had, by August 13, 1877, built a four-game lead in the pennant race, when the team suddenly and inexplicably started losing. The club dropped 11 of 13 (ignoring one tie) before rebounding. Devlin, the only pitcher on the team, had won 30 games the year before and did not pitch especially well during the losing streak.

Boston came from behind, winning 20 of its last 21, to take the championship by seven games. Jack Chapman, the Louisville manager, was suspicious of his club’s collapse and obtained confessions from three of the four players involved, including his pitcher, that they had fixed games. When the evidence was presented to Hulbert after the season, he immediately banned all four players permanently from the League.

In the ensuing years, he turned down numerous appeals from the banned players, including a heartfelt personal plea from Devlin in Hulbert’s Chicago office, a meeting Al Spalding witnessed.23 As Spalding later conveyed, “Devlin was in tears, Hulbert was in tears.…I saw the great bulk of Hulbert’s frame tremble with the emotion he vainly sought to stifle.…I saw him take out a $50 bill and press it into the palm of the prostrate player. And then I heard him say… ‘Devlin, that is what I think of you personally; but damn you, you have sold a game and I can’t trust you. Now go and let me never see your face again; for your act will never be condoned as I live.’”24 More than forty years before the Black Sox scandal would rock the baseball world and a new commissioner would ban the eight players involved for life, Hulbert had taken a similar action. No stronger message could be conveyed that the throwing of games by National League players would not be tolerated.

At the time Hulbert sent that message, his league was facing a growing challenge from the International Association, which emerged from the breakup of the NAPBBP. The IA, founded in 1877, was an attempt to carry on the loosely knit Association. Like its predecessor, it offered more control of the clubs to the players. While mostly a New England and New York operation, it failed to gain clubs in the major eastern markets. Nonetheless, the National League considered it a major threat to its eastern teams and took steps to split the Association by establishing alliances with some of its clubs. These alliances, obtained for a small fee, ensured member clubs the protection of the League, including recognition of territorial rights and player contracts. In this regard, the alliances laid the groundwork for relationships in later years between major and minor league teams.25

Hulbert was facing not only external challenges, but also internal ones. Three of the NL’s original clubs folded after 1877: St. Louis, Hartford, and Louisville, the last largely due to the game-fixing scandal. The three removed clubs were replaced with teams in Providence, Indianapolis, and Milwaukee as the League maintained a six-team format at the start of the 1878 season. Part of the League’s problem was the depressed American economy, which made it a challenge to keep a for-profit entertainment business afloat.26 As a result, 1879 saw another shake-up as the League returned to an eight-team format. Indianapolis and Milwaukee dropped out, while Troy, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Syracuse were added.

By the time the 1879 season ended and the full impact of the new teams and the alliance was assessed, it became even clearer that players “revolving”—i.e. jumping from one team to another—remained a major problem. This issue was especially exacerbated by the poor economy, as the League had been trying to get a handle on its operating costs. In previous years clubs had tried to make players pay for their uniforms and part of their travel, lodging, and meals.27 With players free from year to year to go to another team, however, the major cost—salaries—still proved difficult to control. In the first four years of the National League, salaries made up between 60 and 67 percent of its total operating costs.28 To address this, the NL owners met in Buffalo on September 29, 1879, and adopted the reserve rule, which for close to a century became the single most contentious issue between baseball management and players.

The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser ran two separate summaries of the motives behind the adoption of the reserve. The first ran this way: “The financial results of the past season prove that salaries must come down. We believe that players in insisting upon exorbitant prices are injuring their own interests by forcing out of existence clubs which cannot be run and pay large salaries except at a large personal loss…In view of these facts, measures have been taken by this League to remedy the evil to some extent for 1880. It has also been decided that a uniform contract with players shall be used by each club.”29

The second article, published four days after the league meeting, summarized the reserve: “Finally, it was proposed that each delegate be allowed to name five desirable players from his own club as a nucleus for a team in 1880, and that these chosen men should not be allowed to sign with any other club without permission. This would prevent unhealthy competition and at the same time give each club a majority of its players for next season.”30 In a nutshell, high labor costs and financial struggles necessitated both a uniform contract and the reserving of the best players for the next season. Revolving of the better players would now stop.

While it is clear the major motive behind the reserve was economic necessity, it is unclear who sponsored the idea at the Buffalo meeting. Many thought the reserve was initially instituted to hurt the Chicago team, since it had to that point been the League’s most financially successful team.31 Some analysts of this period have suggested that Andrew Soden, the new owner of the Boston franchise, was the driving force behind the reserve.32 Given Hulbert’s control over the National League, however, and given his persuasive powers, it is difficult to imagine the reserve being implemented without his support. In fact, in 1880, it never would have been renewed at the annual meeting if not for Hulbert’s strong efforts to push it through.33 Given his feelings about labor, his generally demeaning views of ballplayers, and his desire to control costs and revolving, this policy seems a natural fit for Hulbert; in any case, it became another of his major legacies.

Other innovations, commonly thought to be part of the League from the start, included the 50-cent admission price, the banning of alcohol at the parks, and the prohibition of playing on Sundays. While all became a part of the league during Hulbert’s tenure, none was part of the 1876 constitution. All certainly fit within Hulbert’s overall vision of baseball, especially in his idealized composition of the fans. The admission price and banning of booze and Sunday games were geared to attract middle-class white Anglo-Saxon Protestants.34 There was no room for the lower classes, who usually worked every day but Sunday. Such fans would also be kept away by the higher price and lack of spirits. Reflecting the politics of the era, his aim was basically to draw Republicans to the ballpark.

While the League had frowned on lower admission prices, booze, and Sunday games from its conception, nothing in the initial constitution addressed these matters. That changed at the 1879 meeting (where the reserve rule was implemented), when the 50 cent admission price—15 cents going to the visiting team—was added to the constitution. Several clubs voiced concerns about the increase despite arguments that other forms of higher class entertainment had similar prices.35 The following year, Hulbert implemented the other part of his policy, amending the league’s constitution to ban liquor and Sunday games. This time, the greatest opposition came from Cincinnati, one of three remaining cities to have an original NL franchise. The city’s heavy German population and the owners’ ties to local breweries made this policy exceptionally objectionable. The owners protested—one even proclaiming that Hulbert liked his whiskey as much as the next man—and the NL responded by expelling Cincinnati from the League.36 This expulsion came back to haunt Hulbert after the 1881 season, however, for his act had sown the seeds of competition.

At the start of the 1881 season, however, there was no indication that the exiled Cincinnati team would create a problem. In fact, the National League began the season with more stability, and in the best financial shape, since its formation. Hulbert proclaimed that “at no time since the beginning of the League have the clubs been in so healthy a financial condition at the beginning of the season as this year. There is not a ‘weak sister’ among them.”37 Detroit replaced the departed Cincinnati as the eighth team, but the other seven remained. No franchises failed in 1881 and all teams completed their schedules. Perhaps the best evidence of the League’s stability came at the annual meeting at the end of the season. For the first time the meeting “passed without President Hulbert once bringing his fist down on the table till things jiggled.”38 Yet, almost simultaneously, another meeting was taking place in Cincinnati that would challenge Hulbert’s world.

While it had taken a full year, the dissident Cincinnati club assembled a slate of potential teams to form a new league, the American Association (AA), in early November. By the start of the 1882 season, six teams formed the Association: Cincinnati, St. Louis, Eclipse of Louisville, Athletic of Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Allegheny of Pittsburgh. All but the last two cities had once represented the National League.

Two facets of the new Association’s constitution stood out. While the structure, including scheduling, ownership, and territorial rights, paralleled that of the National League, admission cost to games was left to individual clubs (all of which settled on 25 cents), liquor would be served at the parks, and games would be played on Sundays.39 While the imitative management structure was something of a vindication of Hulbert’s views, the threat of competition from a non-puritanical league was definitely not to his liking.

By the time the Association began its 1882 season, Hulbert was dead of heart failure at age 49, a condition perhaps brought on by the new competitive challenge.40 Before his death, Hulbert was clearly preparing to deal with the threat, asserting that “the League does not recognize the existence of any Association of ball clubs excepting itself and the League Alliance.”41 He moved quickly to form alliances with clubs in both New York and Philadelphia to prevent or weaken the new association’s efforts in the AA’s largest population centers.42 There is even some evidence that he had begun to lay the groundwork for the conciliation with the new league that his successor implemented a year later.43 Even in weakening health, Hulbert helped to ensure the National League’s continued well-being.

Perhaps Hulbert’s greatest contribution beyond the initial structure, however, had been his ability to keep the League alive. By the time of his death, the League had seen franchises in 17 different cities and only those in Boston and Chicago had remained part of the League throughout. Similar to the way General Washington had won the Revolutionary War by keeping an army in the field, Hulbert had kept the National League viable by ensuring from year to year that it had enough franchises to present teams with professional talent.

Writer Tom Melville has made the interesting observation that franchise stability, other than the Boston/Chicago axis, was less important to Hulbert than maintaining the indivisible central authority of the League.44 If true, Hulbert’s effort was definitely an unmitigated success, for the League, not its rotating franchises, governed the overall operational success.

Along with a structure that was copied by the new league, and nearly every subsequent league created (the Player’s League of 1890 the one notable exception), Hulbert’s other legacy was his development of a protégé who would help to lead the League after his death. Albert Goodwill Spalding, from the time he was signed by Hulbert to pitch for the White Stockings, became his understudy. Spalding moved from star pitcher to second in command of the White Stockings, largely directing the team’s affairs so Hulbert could focus on League issues. (This may explain in part his early retirement from active play, which likely kept Chicago from winning league titles from 1877 through 1879.) When Hulbert died, Spalding bought out the family interest in the franchise and directed the National League behind the scenes until his retirement from both in 1891.

By that time, Spalding had helped the league in its fight against both the Union Association in 1884 and the Player’s League in 1890. With the latter victory, Spalding helped to ensure the preeminence of the Hulbert model for operating a professional sports team or league. He may not have co-founded the National League, but he definitely helped assure its continued dominance.45 The baton of leadership had been ably passed and the League continued to prevail, even withstanding weak leadership during the 1890’s.

Hulbert left a profound legacy to professional baseball that carried over to other pro sports in America. The capitalist model for team ownership has prevailed not only in baseball, but also in the other major professional leagues. Other than the Green Bay Packers, neither municipal nor player ownership has succeeded in American sports. That has often brought heartache to local fans when their teams have left town, but it has also proven successful both financially and, to some degree, competitively. Hulbert’s creation of defined territory—essentially a monopoly—for a given franchise remains the basis for every current professional sports league. While such a policy seems on the surface to be anti-competitive, it comes out of a rich nineteenth-century tradition in which moguls talked the talk of competition while maneuvering to gain market control. His banning for life of the four Louisville players who threw games in 1877 established a model that Judge Landis, the first commissioner of baseball, used in 1921 to send a similar powerful message about gambling.

The NL’s creation of alliances with other teams and leagues to help ensure its dominance set a pattern that nearly all other leagues would later follow. The reserve rule, established to stabilize the financial viability of teams in the early years, created a major sore spot in labor relations for professional baseball for nearly a century later. In essence, Hulbert created the basic framework within which professional sports in America operate.

DAVE BOHMER is Director Emeritus, Pulliam Center for Contemporary Media and Media Fellows Program, DePauw University. Formerly a telecommunications executive, he has been teaching and researching baseball history for more than a decade.

NOTES

1 James, Bill, in The New Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 33 stresses how significantly this issue impacted Hulbert. Pietrusza, David, in Major Leagues: 18 Professional Baseball Organizations 1871 to Present (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1991), 23, suggests Force’s contract with Chicago was signed illegally; Melville, Tom, in Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001), 72-73 contends that the pressures of playing in Chicago drove Force to Philadelphia.

2 Wright, Harry. Letter to William Hulbert. March 18, 1875. Harry Wright Papers. Albert Goodwill Spalding Collection, New York Public Library. See also David Quentin Voigt, American Baseball: From Gentleman’s Sport to the Commissioner System (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 50 on how the Force case helped to polarize Wright.

3 “Sporting – The Professional Baseball Association – What It Must Do to Be Saved – The Coming Trouble for the Game and Its Remedy,” Chicago Tribune, October 24, 1875 in Early Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1825-1908, ed. by Dean A. Sullivan (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 92-93.

4 This has also been noted in a recent article by Hershberger, Richard, “The Borderlands of Professionalism: Cooperative Clubs and the Formation of the National League,” in Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game. 1.1 (2007): 103-116 as Hulbert’s major motivation in his new efforts.

5 “Sporting – The Professional Baseball Association,” Chicago Tribune, October 24, 1875, in Early Innings, ed. Sullivan, 94-95.

6 Chadwick, Henry. “National League of Professional Clubs – A Startling Coup d’Etat,” New York Clipper, February 12, 1876 in Early Innings, ed. Sullivan, 96.

7 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 5.

8 Chadwick, Henry. The Game of Baseball: How to Learn It, How to Play It, & How to Teach It (New York: George Munro, 1868), 44.

9 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 17.

10 Lamster, Mark. Spalding’s World Tour: The Epic Adventure That Took Baseball Around The Globe – And Made it America’s Game (New York: Public Affairs, Perseus Books, 2006), 21, contends that Spalding was the instigator while Pietrusza, in Major Leagues 24-25, gives the initial credit to Hulbert.

11 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 24.

12 Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 78.

13 Ibid, 80.

14 Rosenburg, John M. They Gave Us Baseball: The 12 Extraordinary Men Who Shaped the Major Leagues (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1989), 18.

15 Wright, Harry. Letter to William Hulbert. December 30, 1875. Harry Wright Papers. Albert Goodwill Spalding Collection, New York Public Library.

16 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 79, Voigt, American Baseball, 62.

17 Vincent, Ted. The Rise and Fall of American Sport: Mudville’s Revenge (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1981), 135-36, Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 80.

18 Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 83.

19 Burk, Robert F. Never Just a Game: Players, Owners & American Baseball to 1920 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 58, Vincent, The Rise and Fall of American Sport, 139, and Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 81. The one exception to this was the Players’ League, which lasted only the 1890 season.

20 Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 81-83, Voigt, American Baseball, 65.

21 Gillette, Gary and Palmer, Pete, Eds. The 2006 ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2006), 1632.

22 Vincent, The Rise and Fall of American Sport, 152, Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 85-88.

23 Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 87-88, Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 92-96.

24 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 38.

25 Vincent, The Rise and Fall of American Sport, 146-50, Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 105-110, Voigt, American Baseball, 73, Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 99-100.

26 Vincent, The Rise and Fall of American Sport, 145.

27 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 39.

28 Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 106.

29 “The NL Adopts a Player Reservation System (1879).” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, September 30, 1879, in Early Innings, ed. Sullivan, 114.

30 Ibid, October 3, 1879 in Early Innings, ed. Sullivan, 114.

31 Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 108.

32 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 43, Zimbalist, Andrew. Baseball and Billions: A Probing Look Inside the Big Business of Our National Pastime (New York: Basic Books; Penguin, 1994), 4.

33 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 115.

34 Vincent, The Rise and Fall of American Sport, 136.

35 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 112-13, Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 91.

36 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 113-14, Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 91-93.

37 Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 119.

38 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 127.

39 Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, 138-39.

40 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 134.

41 Pietrusza, Major Leagues, 73.

42 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 132.

43 Levine, Peter. A. C. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball: The Promise of American Sport (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 51-52.

44 Melville, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, 101.

45 See Levine, A. C. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball, 28-29, on Hulbert as mentor to Spalding, and Chapter 4, 49-70, on the role he played in the National League after Hulbert’s death.